“Young people are making their voices heard”: From Harlem’s Youth Movement in the 1930s and 1940s to DSA-NYC

By Mary Reynolds

The ongoing press scrum over New York’s 2021 mayoral election has obscured the down-ticket candidates in the June 22 primary races for the City’s fifty-one Council seats. These contests could be better bellwethers for the city’s future, and recall a little-known era of the city’s radical past.[1]

Six of the new hopefuls are self-described socialists: Adolfo Abreu, Alexa Avilés, Tiffany Cabán, Michael Hollingsworth, Jaslin Kaur, and Brandon West. Several in this cohort are from immigrant families, and at least two are union members. They all have grassroots organizing experience in either housing and tenants rights, education and youth rights, or criminal justice reform.[2] The New York chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA-NYC), hoping to build on DSA successes in state and national politics during the 2018 and 2020 elections, has endorsed them all. If elected, this multiracial group would add a City Council contingent to the DSA-NYC-endorsed working-class and nonwhite New Yorkers who have already won political office in Albany and Washington DC.

Almost a century ago, another crop of New Yorkers — who also came-of-age amidst economic and political crises — sought to transform the city, country, and world. They forged their organizing and political commitments in the Popular Front’s radical-led coalitions and campaigns for voting rights and political representation. For these young people, the Popular Front was the political theory and organizing model that put anti-racist, feminist, and class-based struggles at the center of their movements for labor and civil rights. Recalling their history offers perspective on New York’s contemporary revival of socialist youth politics, and how such politics have resonated far beyond the five boroughs in the past.

Claudia Jones and the Young Communists

Claudia Jones, who as a nine-year-old emigrated from Trinidad to New York in 1924, joined the Young Communist League (YCL) as a student at Harlem’s Wadleigh High School in the mid-1930s.[3] An activist in and out of the classroom, Jones was “always in the thick of activities, even as a student leader, when I first met her at Wadleigh,” remembered Dorothy Robinson, who later became the first African-American to head Harlem’s 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library.[4]

Claudia Jones at an Anti-lynching demonstration in Times Square, 1939 (Daily Worker, Tuesday April 4, 1939, page 4).

Throughout her early career as a communist journalist and organizer, Jones amplified young New Yorkers’ anti-racist and feminist calls to legislate desegregation, pass a federal law against lynching, and support voting rights. She and several of her classmates joined a burgeoning movement that drew students and young workers into the YCL, the American Youth Congress (AYC) and the Young Liberators, a local multiracial organization dedicated to fighting police brutality and job discrimination, particularly in Harlem’s five-and-dime stores and cafeterias — the Walmart and McDonalds of their day.

New York’s public school system provided Jones with an early spur to such civic engagement at Harlem’s all-girls Harriet Beecher Stowe Junior High School. In 1928, she participated in a “School City” program, which teachers had designed to provide “practical experience in self-government” and encourage “self-control and sound judgment among the girls.”[5] Mimicking the municipal government structure, students ran for Mayor, Board of Alderman (as the City Council was called until 1938), and Department Commissioner seats. Jones threw her hat in the ring for Mayor of School City.

Intended as a lesson in American democracy and citizenship, School City instead taught Jones about building solidarity across perceived racial differences, and the racial and gender limits of political representation in New York. Years later, in an open letter to the Communist Party’s head William Z. Foster, she described her teachers’ attempts to dissuade her from campaigning alongside a Chinese classmate, who was running for Board of Aldermen President. Jones refused the teachers’ entreaties, and both candidates won in the mock election. “We were elected by an overwhelming majority of the students,” she recalled, “proving the teachers wrong and showing the internationalist approach of the student body.”[6] These nonwhite electoral victories existed only within the school walls — until Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. won a City Council seat in 1941, the first African American to do so — but they inspired Jones’s contributions to such campaigns for years to come.

A decade later, Jones, by then a national leader in the YCL, was reporting on activities of the Popular Front youth movement for the communist press. “From the heart of the Southland to the industrial North, from the sunny shores of California to the rocky coast of Maine, conferences of Negro youth are signs of the times,” she wrote in the Young Communist Review.[7] Throughout the spring and summer of 1938 she helped lead and record activities of the YCL-affiliated All-Harlem Youth Congress that drew hundreds of participants. The Congress mobilized a cross-class, multiracial group of radical and civil liberties activists, church members, college students, factory workers, actors, and musicians to demand jobs and educational opportunities for all young people.[8] Delegates passed resolutions on equal pay for equal work, legal protections for domestic workers, and the elimination of poll taxes, literacy tests, and other disenfranchisement practices.

Committed to interracial solidarity and gender equality, many of the Congress’s organizers forged a Popular Front political consciousness in the youth movement, fostering lifelong commitments to the civil liberties and labor movements. The YCL, founded in 1922, and the AYC, founded in 1934, counted thousands of members by the late 1930s, many of whom Jones helped recruit. They urged solidarity with anti-imperialist and anti-fascist struggles, and demanded the extension of the New Deal’s policies and programs beyond liberal priorities to include racial and gender justice in electoral politics, education, and jobs.[9]

Claiming to represent over five million young people by 1938, the AYC had formed a nationwide coalition of young trade unionists, churchgoers, college students, and unemployed workers. If today’s DSA can only dream of the AYC’s boasted reach, the latter’s annual platforms are still relevant today: abolition of the poll tax and other voting restrictions; condemnation of police brutality and lynching; equal pay and education advocacy.[10]

New Faces of Leadership at Home and Abroad

Just like the Justice Democrats and DSA-NYC today, the youth movement of the 1930s and 1940s provided a network of radicals, especially women, with opportunities to lead campaigns. That network included Dorothy Height — a college-educated social worker who later served as the National Council of Negro Women’s president for over forty years — and YCLers Jones and Howard “Stretch” Johnson, two working-class organizers shut out of university classrooms who had instead studied at workers’ schools and YCL training centers.

These new youth leaders linked a local politics celebrating New York and America’s Black history and culture with their battles against both segregation at home and colonialism abroad. During the summer of 1938, Height, Jones, and Johnson joined other AYC and YCL members in collecting signatures for a Book of International Friendship, part of a national campaign to raise funds and awareness for the World Youth Congress (WYC) convention to be held at Vassar College that August.[11] On behalf of Harlem’s Coordinating Committee for Youth Action — a Popular Front umbrella group of over two hundred local organizations — they solicited support from nationally famous figures and state politicians.

Eleanor Roosevelt signed Height’s copy when the young organizer paid a visit to the First Lady at the Roosevelts’ home in Hyde Park, New York.[12] Jones and Johnson visited the Bronx office of William T. Andrews, the NAACP lawyer who represented their Harlem neighborhood in the New York State Assembly. A photograph of the event depicts Jones wearing a broad hat festooned with a jaunty bow, and Johnson, a former Cotton Club dancer, in an elegant suit. Jones leans over the politician’s left shoulder as he ceremonially adds his name to the AYC Book.[13]

By the time WYC delegates from Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America arrived in New York, young Americans had collected over two hundred thousand names in the Book of International Friendship. The August convention “for the first time brought representatives of Negro youth together on a world scale,” Jones later recounted, including delegates from Cuba, Haiti, the West Indies, Ethiopia, and Algiers.[14]

On the morning of August 17, 1938, over five hundred WYC delegates from fifty-four countries boarded a steamboat at the Harlem Pier on West 125th Street and headed up the Hudson River to Poughkeepsie. They were “as diverse in language and complexion as America itself,” the Daily Worker reported.[15] From the opening dinner at Vassar when the First Lady officially welcomed the participants over corn-on-the-cob and blueberry pie, to the last day when the group hammered out compromises on a series of resolutions, young people discussed issues that remain central to the political rhetoric of today’s New York socialists: unemployment, education, racism, imperialism, and peace across the globe.[16]

In a “spirit of fraternity and collaboration between the youth of all nations,” the delegates passed the “Vassar Peace Pact,” a call to action to “set right injustices against peoples, regardless of race, creed or opinion, [and] to establish political and social justice within our own countries.”[17] Reflecting the influences of anti-colonialist youth, the Pact’s Article IV read, “There can be no permanent peace without justice between nations and within nations, or without their recognition of the right to self-determination of countries and colonies seeking their freedom.”[18] The right to self-determination would define young communists’ politics and activism for the next decade, but so would war, fascism, and anticommunism.

Radicalism in a time of war and “recovery”

Despite an increasingly repressive political atmosphere nationally, New York radicals made progress on the home front during WWII. By 1943, women made up more than half of the YCL’s membership, as many YCL men had enlisted in the US armed services and deployed overseas.[19] Called up in October that year, Stretch Johnson completed his basic training on segregated bases in Wyoming and Arizona, then volunteered for combat duty with other Black “Buffalo Soldiers” in the segregated 92nd Infantry Division. By 1945, he was under artillery fire in Italy.[20]

Meanwhile, Jones had caught the eye of FBI officials, who in 1942 made her the subject of a “continuous, active, and vigorous investigation,” recommending that the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) place her on a potential deportation list.[21] While Johnson fought fascism abroad (and earned two Purple Hearts), Jones encouraged young people, especially women, to engage in citizenship activities at home, within a state that was crystallizing its case for removing her as a subversive alien. Denied US citizenship after listing her YCL activities on her Smith Act-mandated Alien Registration form in 1940, she nonetheless joined campaigns to pass the Soldier Voting Act, and efforts to elect Black Americans, including her friend and fellow communist Ben Davis.

Spotlight October 1944

Jones spent the war years as the editor of Spotlight, a monthly Popular Front magazine that the YCL had launched after changing its name to American Youth for Democracy (AYD). The magazine’s purpose, as she described it, was to introduce young people to “anti-fascist education and understanding, inter-racial and inter-faith unity, the democratic traditions of our country, [and] a knowledge of American history.”[22] With a look that replicated Life magazine’s red banner and full-page cover photographs, Spotlight’s front page often featured a movie star or a group of handsome young men in uniform. Celebrities, politicians, journalists, and activists provided articles and editorial support. Frank Sinatra and Humphrey Bogart appeared on its cover, and published articles in its pages. The magazine also ran short pieces about elections and legislation by Democratic US Senators Claude Pepper, a left-liberal from Florida, and Elbert Thomas, an internationalist from Utah.

In her “From the Editor” columns, Jones reported on national campaigns for soldiers’ absentee voting rights, lowering the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen, desegregation and anti-racism in the armed forces, and childcare subsidies and equal pay for working women. While the magazine’s covers displayed only white faces, almost exclusively male, the interior pages detailed the activities of a multiracial, women-led youth movement and its organizations.

Spotlight, August 1944

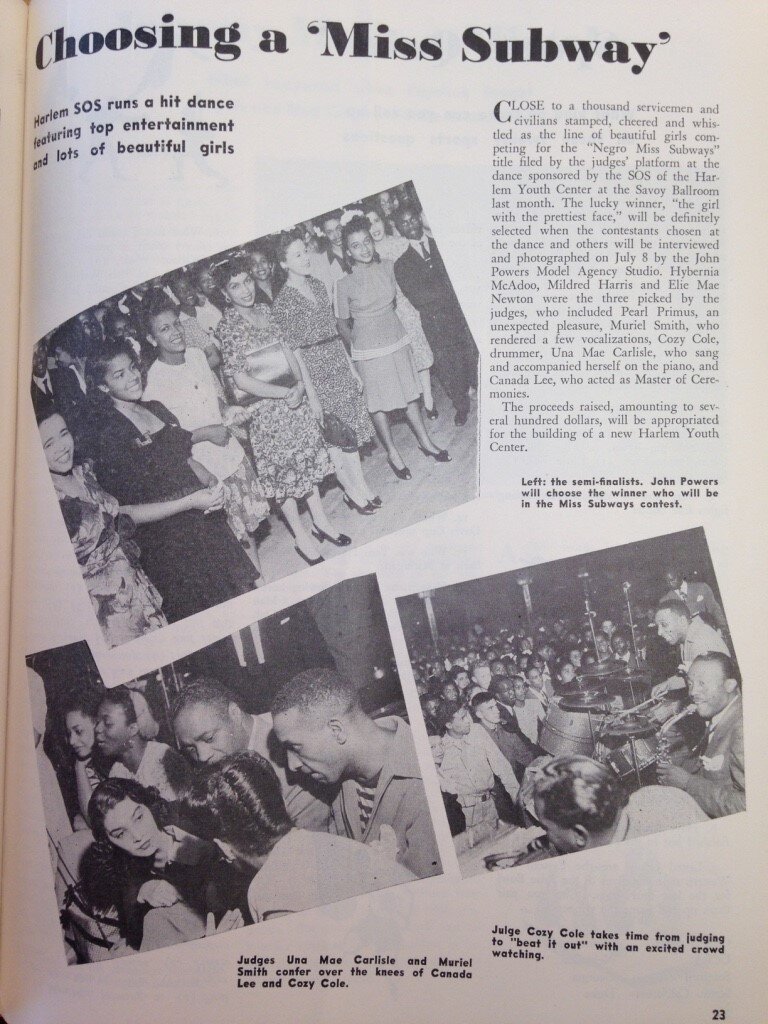

One of those organizations, run out of New York, was the Sweethearts of Servicemen (SOS). In Harlem, SOS members held interracial dances, Red Cross blood drives, and beauty contests at AYD canteens, but they also made feminist demands for government funded childcare nurseries and neighborhood playgrounds, campaigning for a postwar world where “sweethearts,” not just “servicemen,” could enjoy voting rights and job opportunities.[23] “If the girls are qualified, they should have the same opportunity as men in keeping their jobs in the plants after the war,” one Spotlight writer declared.[24]

The Soldier Voting Act of 1942 had made it easier for the eleven million men in the armed forces and thousands of women in the Red Cross and other organizations stationed abroad (and over the age of twenty-one) to cast absentee ballots in the federal election, temporarily eliminating the poll tax and other state voting requirements for all military personnel.[25] It provided new possibilities for Black servicemen from southern states to vote. SOS and AYD members mobilized throughout 1943 and 1944 to support the Act’s renewal, and the permanent elimination of state poll taxes in federal elections. They collected petition signatures, mailed postcards to Congress members, participated in an “emergency conference” with labor unions and the Federation of Women’s Clubs, and organized interracial delegations to picket local politicians and the War Department.[26]

Frank Sinatra on Spotlight's March 1944 cover

In Harlem, many young radical New Yorkers, such as Italian-American Esta Pingaro and Puerto Rican Helen Vásquez, leaders of the Lower and East Harlem Youth Congress, campaigned for Vito Marcantonio, a civil rights lawyer who represented East Harlem in the U.S. Congress in the 1930s and 1940s.[27] Others stumped for Ben Davis, Harvard-educated lawyer and editor of the Daily Worker, who had also garnered support from luminaries Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes in a bid for a City Council seat in 1943. A member of the Communist Party’s National Executive Board, Davis won in a landslide, with just over half of his 44,000 votes cast in majority white neighborhoods, his victory proving the power of multiracial, cross-class organizing.[28]

Backlash and Latter-Day Revival

Authorities and establishment media outlets in the postwar period leaned on anticommunism to criminalize or undermine anti-racist, feminist, and economic justice campaigns, and New York radicals felt their sting. The New York Times painted SOS activists as “immoral women,” quoting an undercover FBI agent who claimed that the Communist Party instructed SOS members “to pick up service men off the streets and bring them to the SOS club rooms where they were given liquor, entertainment, and dancing.”[29] What Jones called citizenship activities, the FBI and The New York Times essentially likened to prostitution.

The youth movement’s mobilizing for the Soldiers Voting Act of 1944 had helped it pass, but the young activists lost the battle to maintain suspension of the poll tax for the nation’s armed forces overseas. “In Mississippi and Louisiana, down in the solid South, we have got to retain our constitutional rights to prescribe qualifications of electors, and for what reason?” one Senator spelled out in his opposition to the Act. “Because we are bound to maintain white supremacy in those states.”[30]

In Harlem, Davis won re-election twice, but after his 1949 conviction under the Smith Act, the New York City Council unanimously voted to remove him from office.[31] Jones, too, was convicted during the government’s sweep of national communist leaders, and each served lengthy prison sentences before the Supreme Court overturned all the Smith Act convictions in 1957.

After the City Council purged Davis, decades would pass before Black women and Asian Americans began winning New York City Council elections. The symbolic election of Jones and her Chinese American classmate to “School City” in 1928 did not become a reality until New Yorkers elected the first Black woman in 1974, the first Chinese-American man in 2001, and the first Chinese-American woman in 2009.[32]

The new generation of New York radicals has already had notable electoral successes. At the state-level, DSA-NYC endorsed Senators Jabari Brisport, Zellnor Myrie, and Julia Salazar, as well as Assembly members Phara Souffrant Forrest, Emily Gallahgher, Jessica González-Rojas, Zohran Mamdani, and Marcella Mitaynes. In the nation’s capital, another DSA-NYC candidate Jamaal Bowman joined Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in January. This elected crop of young working people features teachers, community organizers, and health care workers who won their seats with the support of grassroots coalition organizing and mobilization.

In many respects, these New York legislators and new candidates recall that earlier generation of New York radicals. The revival of anticommunist talking points among national politicians on the right such as Tom Cotton, Ted Cruz, and Marjorie Taylor Greene suggests that they may be eliciting a similar response, updated for a post-Cold War social media age. In this light, next Tuesday’s elections may offer not just a chance to decide New York’s future, but another crack at its past.

Mary Reynolds received her PhD in American Studies from Yale University in June 2021. Her dissertation is entitled "Red Lives: Grassroots Radicalism and Visionary Organizing in the American Century." She is currently a Research and Strategy Consultant with the Reflective Democracy Campaign.

[1] Title quote is from Claudia Jones, “New Problems of the Negro Youth Movement,” Clarity vol 1, no. 2 (Summer 1940).

[2] Annie Levin, “After Sweeping Statewide Races, DSA Aims to Put a Socialist Caucus on New York’s City Council,” In These Times, December 4, 2020.

[3] Carole Boyce Davies, Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007).

[4] Madeleine Provinzano, “Claudia Jones: Heroine from Harlem,” Daily World, February 9, 1974.

[5] Thelma E. Berlack, “Irma Minot Elected Mayor of School City of Girls’ Junior High,” New York Amsterdam News, January 26, 1927. This article describes the 1927 not the 1928 election, but mentions that it will be an annual event.

[6] Claudia Jones, “Autobiographical History,” reprinted in Claudia Jones, Beyond Containment edited by Carole Boyce Davies (London: Ayebia Clarke Publishing.2011), 11.

[7] Claudia Jones, “Recent Trends Among Negro Youth,” Young Communist Review (July 1938), 15.

[8] Howard Johnson and Wendy Johnson, A Dancer in the Revolution: Stretch Johnson, A Harlem Communist at the Cotton Club (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014), 67-69.

[9] Erik S. McDuffie, Sojourning for Freedom: Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Left Feminism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 98; Dayo Gore, Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War (New York and London: New York University Press, 2011), 70.

[10] American Youth Congress, Convention Program August 1934 (New York: American Youth Congress, 1934); “Youth Congress Hits Bias, Urges Passage of Anti-lynch Bill,” New York Age, July 15, 1939.

[11] Lydia Lindsay, “Black Lives Matter: Grace P. Campbell and Claudia Jones—An Analysis of the Negro Question, Self-Determination, Black Belt Thesis,” Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies 12:10 (March 2019), 119.

[12] “First Lady Greets World Youth Meet,” Daily Worker, August 17, 1938; “Mrs. Roosevelt Gives Youth Congress $100,” New York Times, August 10, 1938.

[13] “Assemblyman Supports Youth Congress,” New York Amsterdam News, July 30, 1938.

[14] Jones, “New Problems of the Negro Youth Movement;” “Harlem’s 2 Commerce Associations Plan to Greet Youth Congress,” New York Age, July 30, 1938.

[15] Beth McHenry, “S.S. Robert Fulton Carries a Boatload of History up River,” Daily Worker, August 17, 1938.

[16] Frank Adams, “Mrs Roosevelt Hails World Youth as Best Agents for Peace,” New York Times, August 17, 1938.

[17] Second World Youth Congress, “Resolutions of the Second League of Nations World Youth Congress, Vassar College, August 1938,” reprinted in The International Law of Youth Rights, edited by William D. Angel and Jorge Cardona, (Boston: Brill Publishing, 2015), 129.

[18] Second World Youth Congress, “Resolutions of the Second League of Nations World Youth Congress, 130.

[19] Maurice Isserman, Which Side Were You On?: The American Communist Party in World War II (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1982), 148.

[20] Johnson and Johnson, A Dancer in the Revolution, 94.

[21] Federal Bureau of Investigation, Claudia Jones, File Number: 100-72390.

[22] Claudia Jones, “Minutes, Spotlight Editorial Board Meeting,” June 1944, James Weldon Johnson Papers, Sp 68 M, Beinecke Library, Yale University. The JWJ Papers archive also holds a series of Spotlight issues from 1943-1945.

[23] See stories and photo collages of SOS activities in Spotlight’s February 1944, June 1944, and August 1944 issues.

[24] Hy Turkin, “Cinderellas of the Cinders,” Spotlight vol 2, no. 10 (October 1944), 21.

[25] Molly Guptill Manning, “Fighting to Lose the Vote: How the Solider Voting Acts of 1942 and 1944 Disenfranchised America's Armed Forces,” (2016), https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters/1170.

[26] Claudia Jones, “From the Editor,” Spotlight vol 2, no. 1 (January 1944), 2.

[27] Jennifer Guglielmo, Living the Revolution: Italian Women’s Resistance and Radicalism in New York City, 1880-1945 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 256.

[28] Gerald Horne, Black Liberation / Red Scare: Ben Davis and the Communist Party (Newark, N.J.: University of Delaware Press, 1994).

[29] John Morris, “Red Push Pictured at Senate Inquiry,” New York Times, December 21, 1949.

[30] Manning, “Fighting to Lose the Vote.”

[31] Horne, Black Liberation / Red Scare, 114, 210.

[32] Sabrina Tavernise, “Mary Pinkett, First Black Councilwoman, 72,” New York Times, December 5, 2003; Michelle O’Donnell, “John Chun Lui: Political Trailblazer is Quick to a Microphone,” New York Times, August 22, 2006; Jennifer 8. Lee, “Victories Across City Resonate in Chinatown,” New York Times, September 16, 2009 (Margaret Chin).