When Clinton was King

By Arthur Banton, Ph.D.

On March 12, 1977, when DeWitt Clinton High School of the Bronx defeated McKee High School of Staten Island 73-67 in the New York City Public Schools Athletic League basketball championship game, it marked a turning point in the seventy-four-year history of the league. McKee was vying to become the first school from Staten Island to win the title in the history of the tournament and break the twenty-year stranglehold by the Brooklyn and Bronx schools. For Clinton, the victory was their seventeenth title in school history – the most by any New York City public high school. Unfortunately, it would also be their last as the two-borough dominance over the sport would give way to more balanced competition. The advantage that Clinton enjoyed for many decades in athletics (specifically in basketball) as the largest all-male academic comprehensive high school in the city was slowly diminishing with the presence of new schools, white flight, demographic changes, and shifts in admission policies. Over the next five years, four of the boroughs would claim city titles (Staten Island has yet to produce a city champion in basketball). [1]

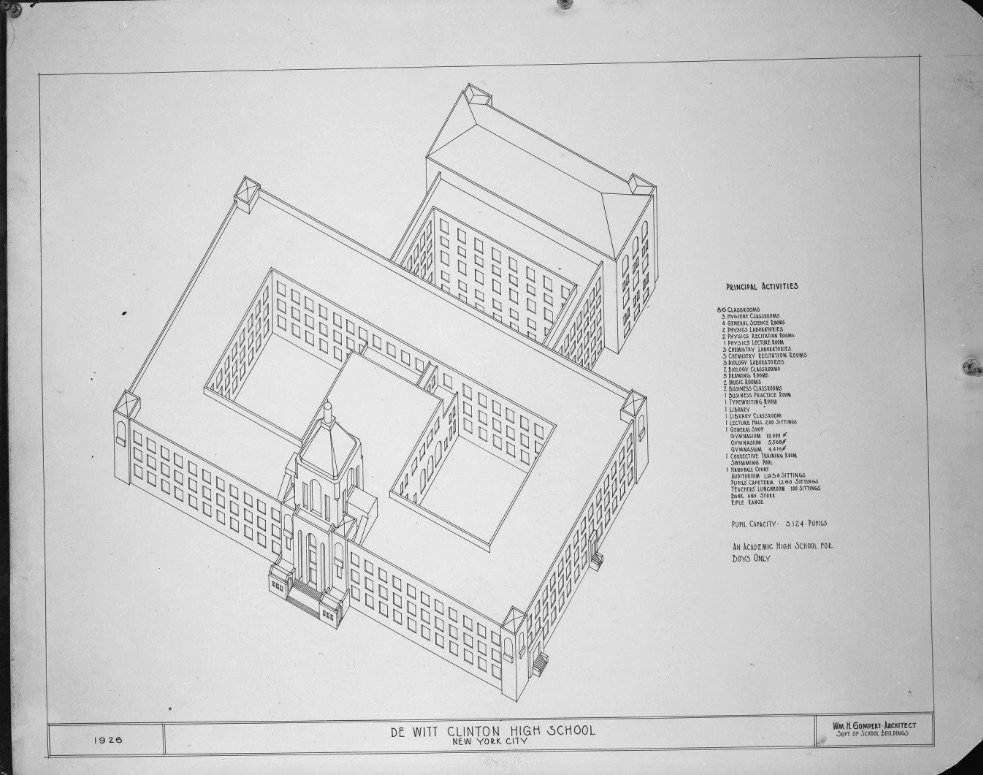

Author Unknown “A rendering of DeWitt Clinton High School,” (New York, NY: NYC Department of Records, April 1927), plate#boe_02879, <https://nycma.lunaimaging.com>.

Since its inception as Boys’ High School in Manhattan in 1896, Dewitt Clinton High School (named after former mayor and State governor) was an academically comprehensive high school that did not impose any geographical restrictions. In other words, it was open to all male residents of New York City who wanted to apply (even though a dominant number of students were from the Manhattan and the Bronx). When the new and current building opened on Mosholu Parkway in the Bronx in 1929, approximately 6,275 students enrolled, exceeding its capacity of 5,124. By virtue of the size of its building and student enrollment, DeWitt Clinton became the largest public single-standing high school in the city and the state of New York. In the context of school size, Clinton was King. In order to accommodate these eager young minds, multiple day sessions were created. Despite the overcrowding and concerns about safety, the school did not compromise any extra-curricular activities nor the quality of instruction. [2] The athletic teams at Clinton were successful in all sports but they excelled and were most noted for basketball.

Basketball was especially popular in New York City and by the turn of the century, nearly every public school was sponsoring teams. [3] The Public Schools Athletic League (PSAL), founded in 1903, was initially a private organization whose primary function was to supervise physical education and interscholastic athletics in all New York City public schools. With about fifteen high schools throughout the city, the PSAL sponsored its first formal basketball tournament in 1905. [4] In that inaugural championship game on March 4, 1905, DeWitt Clinton defeated Boys High in Brooklyn to lay claim to the first ever PSAL tournament champion. In other words, Clinton was crowned the first king of basketball. [5]

This team would claim Clinton 10 th PSAL Basketball Championship. Author Unknown, “DeWitt Clinton 1936-37 Boys’ Basketball Team,” The Clintonian (Bronx, New York: DeWitt Clinton High School, June 1937), 34.

Over the course of the next 75 years, Clinton appeared in twenty-seven PSAL championship basketball games and won seventeen times. One reason that contributed to their unprecedented success was their unique ability to procure talent. Most New York City high schools are designated to serve neighborhoods or some other defined geographical area. Because Clinton was not, it drew from a broader pool of talent throughout the city (most notably from Harlem which did not have a designated high school for boys). [6] In the 1920s and 30s as more “neighborhood schools” were constructed across the city, Clinton maintained this advantage. Only briefly throughout the early and mid-twentieth century did two rival schools, James Monroe High School in the Bronx and Benjamin Franklin High School in East Harlem, respectively challenge Clinton’s well-known supremacy.

Clinton withstood threats from Franklin and other schools during the 1940s by winning two more titles in 1945 and 1947 but the school faced significant challenges during the post-war years into the 1960s as the demographics of the city began shifting. In 1950, the Bronx recorded a population of 1.4 million residents, the largest ever to that point and doubling its previous total in less than 30 years. In that same year, Clinton had a student body that was 70 percent white, the highest number since World War II. Still, as the fifties wore on the population of white students declined dramatically largely through white flight, which slowly eroded the school’s ethnic diversity. Still, the overall population of the borough remained steady with an influx of Puerto Ricans who were migrating from the Island and East Harlem. Though Clinton was not a school bound by geography-based enrollment, the demographic shifts in other neighborhoods affected the student body. By fall 1972, Clinton, still with a student population well over 6,000, had a student body that was 37.2% Black, 33.8% White, and 29% Puerto Rican. [7]

The most immediate significant threat to Clinton was the loss of its reputation as a school that provided an educational experience, in addition to competitive athletics, that inspired success. This legacy and sense of pride (reinforced by alumni) was not lost on the student body. In 1971, about sixty percent of its graduates went to college and the very active alumni association (with its own office on campus) professed an endowment north of $100,000. While this was very encouraging to any prospective attendee, Clinton was still overcrowded. Some of the problems associated with that issue, such as falling attendance rates, student apathy, gangs, drugs, and truancy were becoming a serious concern. [8] In the 1960s, the city tried to address the issue of overcrowding by constructing three large academic comprehensive neighborhood schools in the Bronx (John F. Kennedy High School, North and West of Clinton, while Adlai Stevenson High School and Herbert H. Lehman High school in Castle Hill and Pelham Bay, respectively in the Southeast and Northeast Bronx). [9]

In addition to the construction of more schools, the establishment of a ‘B’ division by the PSAL in 1961 raised problems for Clinton’s athletic competitiveness. The divisions, which classified basketball programs by school enrollment size and strength, were a welcome change for some Vocational schools who had been lobbying for them for a while. They argued that their lower enrollments, poorer facilities, and students’ after-school responsibilities created a smaller pool of talent for their varsity teams and, as such, the schools were greatly disadvantaged in competition against comprehensive high schools like DeWitt Clinton. This subtle move initially appeared insignificant, but it would inevitably be one of the proverbial dominoes that would topple Clinton’s crown in basketball. [10]

Photographer Unknown, “DeWitt Clinton High School,” The Clintonian (Bronx, New York: DeWitt Clinton High School, June 1941), 2.

Many of schools that feared Clinton or were soundly beaten by the school, were winning championship titles in the ‘B’ division. Between 1969 and 1974, all of the lower-level basketball championship titles were won by Bronx schools, including the Bronx High School of Science, a school less than a few hundred yards away from Clinton’s campus. [11] In 1973, in its second year of fielding a varsity basketball team, Adlai Stevenson was holding up a championship trophy in the ‘B’ division. However, the writing was on the wall. It was only a matter of time before Stevenson moved up to the ‘A’ division, joined by two other large Bronx high schools that had only recently been opened, Kennedy and Lehman. Internally, Clinton was facing its own problems, as enrollment started to decline throughout the 1970s. [12]

By 1982, Clinton’s student body stood at 2,300, only a third of its enrollment size a decade earlier. A building that was constructed for 5,124 was now at less than half capacity. While the population of the Bronx did drop 20.6% between 1970 and 1980, that only explains a portion of the issue. Other factors contributing to Clinton’s decline was the construction of more neighborhood schools, some with more modern amenities, that young men could attend closer to their homes. Another factor was the fact Clinton only accepted male students. Many young men did not find attending a single-sex school particularly appealing nor did they appreciate the advantages of this arrangement like previous generations. Also, Harlem students had several additional school options just a short train ride away to the south.

In 1975, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. High School on Amsterdam Avenue on West 65th street opened its doors and in 1978, Park West High School on 525 West 50th Street followed. These schools provided students in Harlem additional options to stay in Manhattan as opposed to traveling to the Northwest Bronx. Finally, the lack of geographical enrollment imperative that had worked in its favor for decades had become a detriment. With no pool of students required to attend, Clinton was forced to rebrand their identity and in September 1983, they did so by becoming a co-educational high school. Administration could no longer ignore 50% of the population. A school that prided itself on a rigorous academic curriculum, superior extra-curricular activities, decades of athletic success, and faculty that would be impressive to many colleges was now talking about survival. [13]

Four years later, DeWitt Clinton made their last appearance in a basketball city championship game. The school no longer had the athletic advantage nor was it viewed as desirable destination for many of the city’s most talented athletes. The school could not stave off a new generation of basketball powerhouses from Brooklyn and Queens that for decades had been nipping at their heels. In other words, Clinton was no longer the king of New York City public school basketball. Their reign ended in 1979 with a 61-55 loss to Boys High School in the PSAL championship game. The following year in 1980, Adlai Stevenson that was constructed to alleviate overcrowding at Clinton in 1971 was no longer regulated to the ‘B’ division. They were the champions of the ‘A’ division and the new kings of the city with an enrollment of 4,276 students – 7% over the building’s capacity. [14]

In the early 2000s, DeWitt Clinton’s academic performance regressed significantly to the point that there were serious discussions about closing the school and carving it into multiple schools. Clinton’s plight was noteworthy, not just because of its history and prominent alumni but because unlike most of the other schools that were phased out, Clinton was not a neighborhood high school. All students had to apply for admission. Instead of closing the school, the city gave its administration an opportunity to resurrect the success of its past into its present and future.

In 2022, Clinton reported 1,052 students enrolled for the academic year and a four-year graduation rate at 94%. Despite the changes in New York City in the last few decades with new schools, demographic shifts, white flight, modifications in admission policies and the trend of creating smaller classroom communities that decimated its school enrollment over the years, DeWitt Clinton High School still remains dedicated to its mission of excellence in academics and athletics. Its basketball program is a reflection of this and even though it’s no longer dominant as it once was, there are signs that echo its storied past. Last season the boys’ basketball team went undefeated (12-0) in their Bronx division before losing in the playoffs. Even though the team fell short of reaching its goal of winning a PSAL championship, they should take solace in the fact that no high school in the City of New York has a history or a story like theirs. It’s just going to take more time to write another chapter to that legacy. [15]

This piece was adapted from “Basketball, Books, And Brotherhood: Dewitt Clinton High School as Scholastic Model of Postwar Racial Progression and African American Leadership” published in the Journal of Higher Education Athletics & Innovation.

Arthur Banton is an Assistant Professor of History at Tennessee Technological University. He is presently working on a manuscript about the New York City Public Schools Athletic League, Basketball, and the City College of New York, which is under contract with SUNY Press.

[1] Bill Travers, “Unbeaten Clinton Subdues McKee for PSAL crown,” The New York Daily News, March 13, 1977; PSAL Boys Champions, < https://wilburcoach0.tripod.com/psalchamps.html>.

[2] Gerald J. Pelisson and James Garvey, The Castle on the Parkway: The Story of New York City’s DeWitt Clinton High School and its Extraordinary Influence on American Life (New York: Hutch Press, 2012), 55.

[3] James Naismith, Basketball: It’s Origin and Development (New York, NY: Association Press, 1941) 7.

[4] Flushing High school was the first PSAL basketball champion in 1903 based on its total victories that season.

[5] Gary Hermalyn, Morris High School and the Creation of the New York City Public High School System (New York: Bronx County Historical Society, 1995), 107.

[6] Wadleigh High school for Girls opened in Harlem in 1902 on West 114th Street but closed in 1954.

[7] Mary Ann Giordano, “Fast Times at Clinton High,” The New York Daily News, June 19, 1983.

[8] Giordano.

[9] Clayton Knowles, “Wagner Seeking 27 New Schools in works Budget,” New York Times, February 1, 1965.

[10] PSAL answers plea, NYT, January 18, 1961.

[11] Michael Lachetta, “Scholastic Sports” The New York Daily News, February 12, 1967.

[12] Leonard Buder, “Schools Opening Today with Force of Security Aides,” September 11, 1972.

[13] Edward Hudson, “2 New Business High Schools to open in Manhattan in Fall” New York Times, April 23, 1975; Jane Perlez, “knives and Guns in the Book Bags strike Fear in a West Side School,” New York Times, December 10, 1987.

[14] Bill Travers, “It was ‘The High’ time for Boys,” The New York Daily News, March 12, 1979; Board of Education, “Final Evaluation Report Adlai E. Stevenson High School Comprehensive Bilingual Education Program, 1979-1980,” 8.

[15] Raphael Sugarman, “DeWitt Clinton riding high,” The New York Daily News, May 8, 1997; Elizabeth Harris, “After Closing Schools, a Principal Fights to save a Bronx High School,” November 26, 2014; “Basketball Boys Varsity Standings 2022-23, A-Bronx II Division,” <www.PSAL.org>; “Dewitt Clinton High School Enrollment (2022-23),” <www.data.NYSED.gov>.