From Rome to New York: The Angel of the Waters

By Maria Teresa Cometto

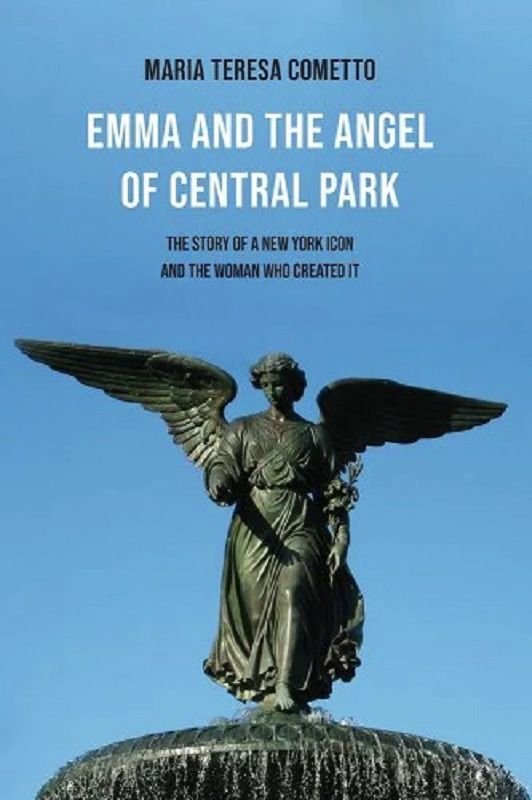

Cover of Emma and the Angel of Central Park: The Story of a New York Icon and the Woman Who Created It, the work upon which this article is based

by Maria Teresa Cometto

Bordighera Press

June 2023, 238 pp.

In the heart of Central Park there is an angel. It is the Angel of the Waters statue, which appeared on the Bethesda Fountain on May 31, 1873. It has since earned a place among the city’s icons — a deserved place for its classical beauty, although not everyone knows that it is much more: a symbol of love, harmony, healing, and rebirth, as the historical motivation for its creation affirms. Scenes from countless movies have been filmed at its feet. In Disney’s fairy tale Enchanted (2007), a worldwide box-office hit and one of the most cheerful and imaginative, the protagonist Giselle sings That’s How You Know — that’s how you know if it’s true love — in the fountain square, surrounded by a festive and colorful musical ensemble. At the end of the song (nominated for a 2008 Oscar), Giselle is seen with her arms raised like the wings of the angel behind her.

Another scene that takes place in front of the Bethesda fountain is the last of another play about love: Tony Kushner’s 1991 play Angels in America, applauded as one of the most poignant dramas of the twentieth century.

“This is my favorite place in New York City. No, in the whole universe,” exclaims the protagonist Prior Walter, a gay man with AIDS. And the Angel of the Waters is his “favorite angel.” He knows that in the time of Jesus by touching the water of the Bethesda fountain in Jerusalem with his foot, the angel made it miraculous: The sick, blind, lame, and paralytic flocked to it, and those who immersed themselves in it emerged healed. Prior dreams of the day when homosexual love will no longer be discriminated against and AIDS patients will no longer be condemned to die secretly, as in the 1980s.

So everybody knows the Angel of the Waters and Bethesda Fountain, but very few know that it was a woman who created them, and a gay one at that: Emma Stebbins. Born in New York City in 1815, she was one of the most famous and applauded American sculptors in 1863 when she got the commission for the fountain, the first woman to be commissioned for a public artwork in New York City. But after the inauguration she retired from artistic activity and was soon forgotten.

When Emma died in 1882, the New York Times did not dedicate an obituary to her, or even a news item. Only in 2019 it published an article on her for its “Overlooked” series: a posthumous tribute, atoning for the newspaper’s silence on such a remarkable artist.

Was the silence due to Emma’s nontraditional life style? There was no doubt that she was gay. “Do you not know that I am already married and wear the badge upon the third finger of my left hand?” wrote actress Charlotte Cushman, referring to Emma in an 1858 letter to another woman. Charlotte and Emma’s relationship, which began in the winter of 1856 in Rome, would last a lifetime albeit amid jealousy, dramas, and betrayals, just as with any couple.

But how was it possibile for two women living together as a couple in puritanical America of the second half of the nineteenth century and in the Rome of the popes? Emma went to Rome in 1856 because the Eternal City was, between the 1850s and 1870s, “the place to be” for an artist. And it was there that the inspiration for the Angel of the Waters came to her.

She was one of the protagonists of that “strange sisterhood of American ‘lady sculptors’ who at one time settled upon the seven hills in a white, marmorean flock.” This is how the contemporary writer Henry James labeled them, with an air of condescension that oozed sexism: the refusal to consider women capable of being true artists, creative and professional, namely, the real reason for the curtain of silence that descended on Emma and many of her other female colleagues.

At that time American women sculptors were attracted by the enormous heritage of antiquities they could study by visiting the Vatican Museums, the Capitoline Museums, and Villa Borghese. Statues such as the Apollo del Belvedere represented the ideal of beauty from which they could draw inspiration to create new works according to the canons of Neoclassicism, the style adopted by the young American republic as the highest artistic expression of the values of freedom and democracy on which it was founded.

But there were also technical and professional reasons for choosing to move to Rome. The finest raw material — the marble of Carrara and Seravezza, the same marble used by Michelangelo — was available in nearby Tuscany, as was the abundant labor of Italian artisans, expert carvers. And for a woman to imagine a career as a sculptor in those days, with her own studio and clientele, was only realistic in such an artistic and international environment as Rome.

Away from their families, Emma and other American female sculptors were free in everything. Even to weave relationships outside the traditional box. Many entered into “romantic friendships” with each other or with other women: a definition that at the time could encompass a wide range of sexual behavior, from chaste cohabitations based on spiritual affinity or the need for companionship and support among unmarried women, to lesbian love affairs. While the puritanical mentality did not even conceive of women as capable of sexual desire and considered these relationships as “chaste,” in Rome the regime of priests used to “let go” whatever was outside the sphere of their particular needs.

The spark between Emma and Charlotte ignited shortly after the former’s arrival in Rome in 1856. Four years earlier Charlotte had chosen to set up house in the Italian city to rest from her long and grueling tours throughout America and Britain. The actress was not beautiful. The features of her face were masculine, and her body constitution was massive. But her success in the theater was enormous. She could win over audiences by playing the most diverse roles, including male ones. They applauded her when she played Lady Macbeth and, with equal enthusiasm, when she took on the role of Romeo. Strong, decisive, passionate, a shrewd steward of her own image and financial fortune, Charlotte was also generous to her expatriate artist women friends in Rome. She hosted them, helped them, promoted them within the art world, and defended them from the envy and attacks of male competitors.

Emma liked everything about Charlotte, the stately bearing, the bright spirit, the piercing eyes. She fell in love with her and did never leave her, even when she suspected that she was being betrayed.

Did she choose not to abandon Charlotte because without her — without her encouragement and help in solving all the practical problems of artistic activity, including getting paid — she could not survive? Some critics dismiss her in this way. But Emma’s unsparing commitment to sculpture shows how ambitious she was, and brave and strong when she needed to be.

Her colleagues, both male and female, employed skilled Italian craftsmen to rough out marble blocks based on their models and engaged with the chisel only in the final stage of statue creation, as indeed did Antonio Canova, the greatest exponent of Neoclassicism in sculpture. Emma, on the other hand, did everything herself, with maniacal perfectionism. Hours and hours of tiring work and dangerous because of all the marble dust inhaled, which would eventually prove fatal to her lungs.

But it was not all toil and sweat. With Charlotte, Emma enjoyed the Roman Dolce Vita. Together they threw parties every Saturday night at their home at 38 Via Gregoriana, a stone’s throw from Trinità dei Monti. With friends they took long rides in the Campagna. And they frequented the salons of other expatriates, where they discussed art and even politics.

The issues to talk about were hot. In the Rome that would remain under the popes until 1870, Americans cheered for the Risorgimento and the liberation of Italy from foreigners. At the same time, they supported the emancipation of slaves in America, holding their breath for the end of the Civil War that had split their country in two since 1861 — the year the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed.

The idea of the Angel of the Waters was born in this atmosphere. Emma drew her design and presented it to the Central Park commissioners as early as 1861. Having obtained the commission in 1863, she worked in Rome to create her model until 1867, when she sent it to a Munich foundry to be made in bronze.

It is true that accusations of nepotism weigh on this commission: Emma’s brother Henry George Stebbins was one of the commissioners who decided on work in the park. But he was also a true lover and connoisseur of art, the only commissioner with “strong taste,” according to Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who, with Calvert Vaux, designed Central Park. The integrity of Henry Stebbins was widely recognized.

Significant is the lack of protest on the part of the architects against Emma’s selection, and in particular the silence-consent of Olmsted, who instead on numerous other occasions opposed the commissioners’ choices. And more than anything else it matters that it was Emma who came up with the idea for the Angel and made it a masterpiece. This is confirmed by both the Central park commissioners’ annual reports — from 1857 to 1875 — and the biographies of Olmsted and Vaux: No one else took authorship of the Angel that makes the waters miraculous and heals the sick, the perfect metaphor for celebrating, with the fountain, the first aqueduct that brought clean water to New York. Until the Croton Aqueduct opened in 1842, in fact, people in the city were dying of cholera and other terrible diseases because the local wells were polluted.

Besides the Angel of the Waters and Bethesda Fountain, Emma created many other statues evincing some surprisingly modern and anticipating trends that would take hold long afterwards.

Such are the marble statues Industry and Commerce, commissioned by entrepreneur Charles Heckscher, which are currently in the permanent collection of the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington Village (Long Island, New York): Emma was the first among American sculptors to take two workers as her subjects — a miner and a sailor — and depict them realistically, in their everyday clothes, while celebrating them as classical heroes.

Emma was also the first American woman sculptor to represent the male nude with the statue The Lotus Eater: a completely bare young man, with only a frond of flowers and lotus fruits covers his private parts. The female nude was considered scandalous by many Americans, let alone the male one.

In Brooklyn you can admire three other works by Emma: the marble bust of another brother of Emma’s, John Wilson Stebbins, at The Center for Fiction; the marble statue Samuel in the Luce Visible Storage of the Brooklyn Museum; and the larger than life-size marble statue of Christopher Columbus in front of the New York State Supreme Court. (Columbus is a controversial figure today, but in nineteenth century he was favorite theme of American painters and sculptors: the lone, daring, and enterprising hero who braved the unknown seas and started out as an underdog but triumphed against all obstacles, paving the way to a continent free of kings and welcoming to those seeking a new beginning.)

In Central Park Emma’s Angel still shines with androgynous beauty. It exudes an intriguing and mysterious aura, barely touching the water with her feet with a light dance step, but at the same time she appears powerful, full of vital energy.

Indeed, in the inauguration program Emma referred to the Angel as a female creature. But the (anonymous) New York Times critic panned the statue for being too masculine. “The head is distinctly a male man,” he wrote, “the breasts are feminine, the rest of the body is in part male and in part female.” The Angel is an absurd “mosaic” of the two sexes, the critic concluded, scandalized.

How obtuse, sexist, and retrograde that judgment appears to us today. That view, in any event, has not dented the popularity of Emma’s creation.

The classical beauty and the message of love and saving purity of the Angel of the Waters have ridden out the evolution of social mores and tastes and not only weathered well the wear and tear of the years. The fountain has gradually consolidated its position as the heart of the park, itself the heart of Manhattan and the entire city.

Never content with her own work and always striving to pursue the highest artistic level, Emma would surely be proud of and satisfied with how much we appreciate the legacy she has left us.

She is now sleeping on the hill. It is the hill at Green-Wood Cemetery, the Brooklyn cemetery where “well-to-do” New Yorkers in the second half of the nineteenth century chose their final resting place.“ It is the ambition of the New Yorker to live upon the Fifth Avenue, to take his airings in the Park, and to sleep with his fathers in Green-Wood,” wrote the New York Times in 1866.

Emma’s grave is in the shadow of a giant pine tree. A simple, small marble headstone marks it. “Emma Stebbins, the Beloved Sister and Faithful Friend.” There is no reference at all to her art, sculpture. At the bottom, there is another small inscription, barely legible: “Love is the fulfilling of the law.” It is another biblical reference. It is part of St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans. The apostle summarizes all of God’s laws in one precept: “Love your neighbor as yourself. Love does no wrong to its neighbor. Therefore, love is the fulfillment of the law.”

St. Paul wrote this two thousand years ago; Emma made it her own a century and a half ago. The couples of all colors and make-up who from all over the world choose the square around the fountain in which to declare their love, make it true every day: Love is love is love.

Maria Teresa Cometto is the author of the first biography of Emma Stebbins, the basis for this article, Emma and the Angel of Central Park: The Story of a New York Icon and the Woman Who Created it (2022, Neri Pozza; 2023, Bordighera Press). An Italian American journalist, she is based in New York City and has been working for almost 30 years at Corriere della Sera. She is the author of La Marchesa Colombi: Life, Novels and Passions of the First Woman Journalist of Corriere della Sera (2020, Solferino); Brothers of the Mountains: Arturo and Oreste Squinobal from the Alps to the Himalayas (2019, Corbaccio; 2020, KDP); Tech and the City: The Making of New York's Startup Community (2013, Guerini/Mirandola Press).