Streets in Play: The Playstreets Photographs of Katrina Thomas

By Rebekah Burgess and Mariana Mogilevich

Brooklyn. Katrina Thomas, 1968, NYC Parks Photo Archive.

In the turbulent summer of 1968, New York City Mayor John Lindsay’s Urban Task Force deployed a range of public programs to keep children entertained and city streets cool, and hired photographer Katrina Thomas to document the city’s efforts. Between June 20 and August 14, Thomas produced nearly 1,800 images, including 500 frames focused on playstreets: residential blocks closed to traffic and equipped with games and other activities. Thomas was a freelancer, not a city staff photographer, so the negatives were her own to keep after the contract ended. Because of Thomas’ independent eye, many of the strongest images taken were not applicable to the assignment, and thus these exceptional frames were left unprinted in the photographer’s personal collection for decades. Over thirty years later, Thomas donated the Urban Task Force negatives to New York City’s Department of Parks. It is one of the most complicated, yet revealing, bodies of imagery in the agency’s archives. The multi-layered street views show the inherent tensions and delicate balance struck between the demands of a commissioned project and the photographer’s particular perspective, as well as offering a multitude of meanings and views of city streets and play.

Photographs of recreation programs like this one were commissioned to offer visual proof that, after four summers of nation-wide protest and violence, starting in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant in 1964, the city was compensating for a long-term lack of investment in low-income, racially segregated neighborhoods. With the assignment there was an expectation of the imagery that the photographer would provide, delivering a visual representation of the municipal message.

In less adept hands, the graphic argument relied on generic imagery and paternalistic tropes, more symbolic than specific: poor children of color receiving municipal attention, and consequently prevented from delinquency or insurrection. Indeed, Thomas had photographed Playstreets for the Task Force the previous summer. The 1967 images feature smiling children neatly lined up in rote poses and wearing t-shirts branded with the names of the corporation underwriting a particular Playstreet and its programming.

By the summer of 1968, the photographer’s visual approach had undergone a massive shift. A few of Thomas’ images were utilized for official purposes, reproduced in pamphlets to attract or to thank program sponsors, but her exceptional eye transcended the municipal task. Her lens recorded the city's sponsored activities as well as the more candid action at the edge of the frame. These captivating, impromptu images provide a rare perspective on a distressed urban landscape, privileging a child’s-eye view of the possibilities for play and delight. Thomas’ images are in conversation with representations of social life or physical conditions by photographers focused on streets in this period (think Helen Levitt or Bruce Davidson), but they resist neat categorization. Her viewpoint throughout is on the life lived in the city’s public spaces.

What are 500,000 kids in the ghetto going to do when school lets out on June 28? New York Urban Coalition, 1968. Courtesy Katrina Thomas Papers, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

Playstreets was a longstanding initiative that took on new significance for the Lindsay Administration. New York City’s Police Athletic League (PAL) began administering Playstreets in 1914 in an attempt to provide safe play spaces and wholesome activities for kids in low-income, high-crime neighborhoods. In 1967 and 1968, the Lindsay administration rolled the PAL Playstreets program in with a series of initiatives intended for “the most depressed areas in New York City.”[1] Attempting to address major racial inequities expediently and in the context of declining public budgets, the city solicited private support for a slate of summer programs. Brochures from the New York Urban Coalition exhorted corporations to sponsor playstreets and sprinkler caps alongside field trips, musical performances, and summer jobs.

Children’s play took on renewed political importance in the late 1960s. When the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (better known as the Kerner Commission), of which Mayor Lindsay was vice chairman, issued its report in February 1968, it singled out “poor recreation facilities and programs,” and the visible neglect of streets, parks, and playgrounds, as important causes of the civil violence of the period. Opening up public spaces was faster and cheaper to improve than systems of housing, welfare, or education.

Brochure featuring Katrina Thomas photographs of past Playstreets. How I Spent My Summer: Mayor John V. Lindsay’s Summer Report to the Private Sector. Mayor’s Commission on Youth and Physical Fitness, Summer 1968. Courtesy Katrina Thomas Papers, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

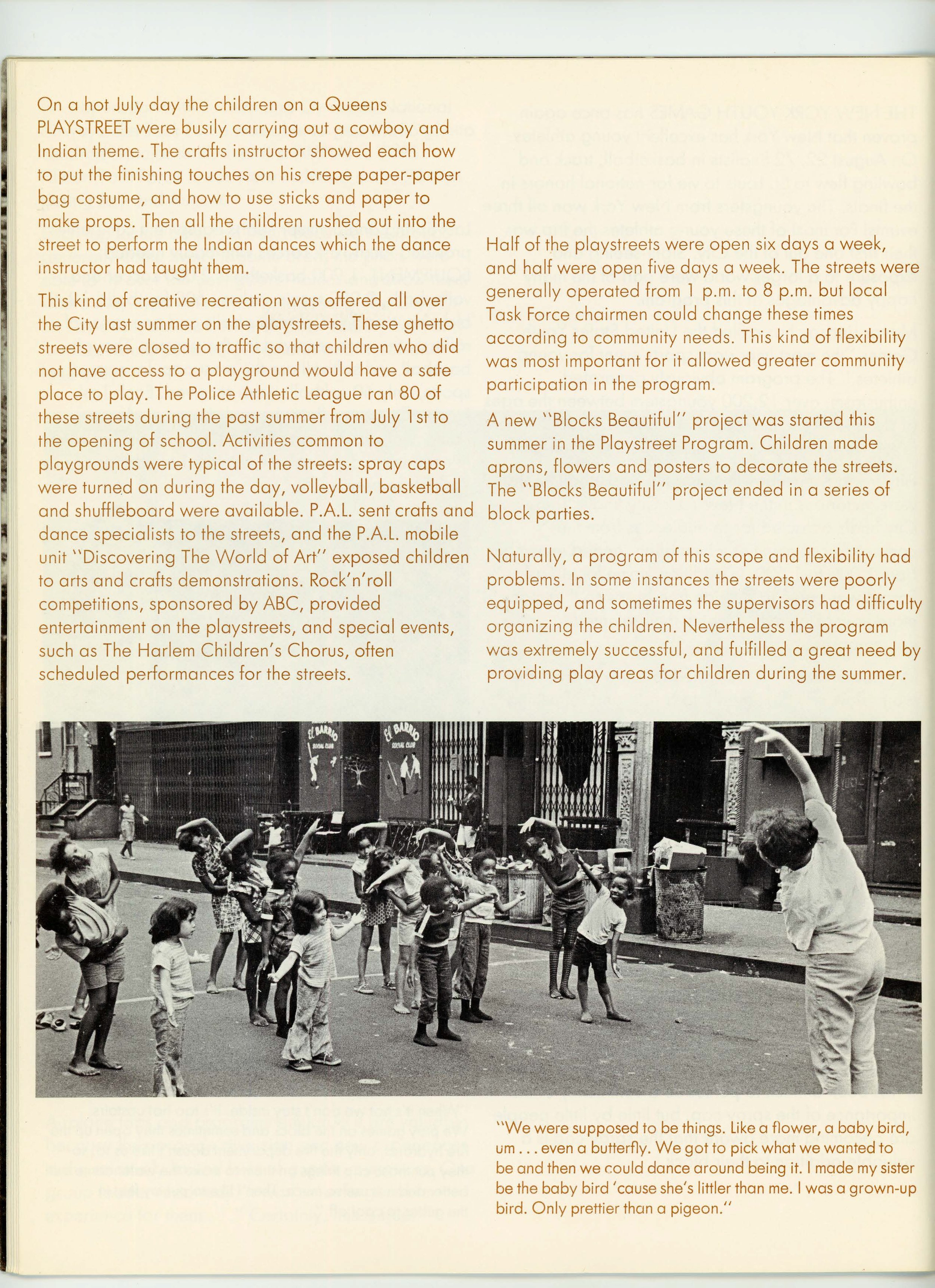

Playstreets were closed to traffic most afternoons in their Lindsay-era incarnation. Staff set up equipment, organized activities, provided instruction and adult oversight. Katrina Thomas’ camera cataloged the range of official diversions: games of chess, volleyball, basketball, dance, crafts, snacks. Yet if the scheduled activities were instrumental to Playstreets, Thomas was also attentive to how they played out in real life, where children were not passive subjects but active protagonists.

One of Thomas’ Playstreets images published in a fundraising brochure, How I Spent My Summer: Mayor John V Lindsay’s Summer Report to the Private Sector, depicts a Lower East Side Playstreet employee guiding a group of children through a ballet lesson. The synchronous movements of the students and teacher within the tightly cropped frame as well as the choice of a classical ballet position are visually emblematic of the program’s aspirations. Though out of the classroom, the teacher’s authority over the students is clear. The teacher imparts rarified ballet steps to the students rather than sharing in a popular dance that the children might already know, a conscious choice of city programmers to elevate a program about play to a form of education or edification.

Unpublished Katrina Thomas image of Playstreets. Lower East Side. Katrina Thomas, 1968, NYC Parks Photo Archive.

In contrast, an unpublished image from the same set depicts the same group of children after the lesson has ended. Here the young dancers show far more imagination and creativity than under the direction of Playstreets staff. The mirrored movements vanish, as does evidence of ballet. Thomas allows the children’s natural movements to activate the tableau. Unlike the tightly cropped brochure image, the more dynamic and open composition encompasses nearby shops and neighbors. The published image is a focused graphic argument about the goals of Playstreets programming; the outtake image exhibits Thomas’ preferred framing of children as vital catalysts of play rather than docile subjects to be directed.

Brooklyn. Katrina Thomas, 1968, NYC Parks Photo Archive.

Thomas’ lens frequently veers away from official programming, following children engaged in more inventive, autonomous forms of play than those provided by the Playstreets. Catalyzed by the invitation of carless streets, and with imaginations unleashed, a milkcrate becomes a makeshift wagon; a clothesline transforms into a tightrope for a young acrobat. Thomas’ uncommon ability to visually engage children without interrupting organic play is evident throughout the Playstreets sets. In contrast to images of streets turned battlegrounds – familiar from the era’s civil rights confrontations in the South or urban uprisings in the North – the Playstreets images offer a vision of the city as "a wonderfully varied playground." Thomas had used this phrase a few years earlier in a book presenting "a child's view of New York.”[2] On the Playstreets blocks, children activate the unscripted performance on the cleared stage of a car-free street. They visually shift from the sidelines to center stage.

Brownsville. Katrina Thomas, 1968, NYC Parks Photo Archive.

Thomas’ lens often lingers on the adult world lining the periphery of children’s play. She pulls focus from foreground to background to capture the many uses of the street’s multi-generational spaces. The block becomes the public stage for intimate, emotional, and joyous experiences at all ages. Thomas’ crucial reframing depicts the ways in which residents inhabit a neighborhood on a daily basis rather than as summoned for a special event. These portraits also belie depictions of a pathologized "culture of poverty" that dominated outside understandings of the 'inner city' at this time.

East New York. Katrina Thomas, 1968, NYC Parks Photo Archive.

The placement of Playstreets took Katrina Thomas to scenes of profound disinvestment, and these streetscapes – with abandoned buildings, vacant lots, no trash collection – also made their way into her images. Thomas’ assignment was not to document “blight,” as in so many photographs singling out scenes of urban decline to argue for redevelopment. Nor was it her inclination to romanticize deterioration, creating what we would now call ruin porn.

Instead, there is a matter-of-factness to urban landscapes that are materially shocking. Children are photographed playing among burned-out buildings not to elicit viewers’ shame or sympathy, but because that is where they play. Unstaged and in the background, the streets of Brownsville, East New York, Harlem, the Lower East Side and elsewhere are not abstractions of despair, but the settings for intense social life. Throughout her career (spanning commercial children’s portraiture to photojournalism and ethnography), Thomas showed consistent interest in the ways that people create spaces for celebration and belonging, in an environment where their needs and desires are often sidelined. In this case, although her assignment was oriented to the specific historical needs of the adults who commissioned her, and their narrative of municipal intervention and improvement, Thomas focused on residents’ universal capacity to transform urban space to their own purposes. In turn, the archive itself provides a new perspective on a place and a time that have long been perceived through a narrower lens.

Adapted from an exhibit at the Arsenal Gallery, NYC Parks Department, Summer 2022, titled “Streets in Play: Katrina Thomas, Playstreets Photographs, NYC, Summer 1968.” Curated by Rebekah Burgess, former NYC Parks Photo Archivist, and Mariana Mogilevich, historian of architecture and urbanism and Editor in Chief, Urban Omnibus.

[1] What are 500,000 kids in the ghetto going to do when school lets out on June 28? New York Urban Coalition, 1968. Courtesy Katrina Thomas Papers, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

[2] Penny Hammond and Katrina Thomas. My Skyscraper City: A Child's View of New York. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963.