A Seat at the Table: LGBTQ Representation in New York Politics

Reviewed By Dani Stompor

“We cannot go back”

As I sit down to reflect on traversing through LaGuardia and Wagner Archives’s digital exhibit A Seat at the Table, my newsfeed is inundated with a litany of legislation and court orders targeting abortion access, transgender athletes, access to hormone replacement therapy for trans youth, inclusive curricula in schools, and drag performances. There has been a marked increase in anti-drag and anti-LGBTQ protests in New York, as well as the appearance of swastika graffiti across the city, including a series of incidents at Queens College. Talking with current LGBTQ undergraduates, I’ve noted how jarring it has been for many of them to witness in rapid succession the overturning of Roe v. Wade and what feels like, in their words, “a race to be the state that hates gay people and women the most.” Numbness and irony tend to be the ruling emotions of the day. It comes as an immense relief, then, that photographer Thierry Gourjon-Bieltvedt and historian Stephen Petrus bring a collection of stories perfectly timed to jolt its viewers away from doomscrolling the latest headlines from The Atlantic and The New York Times.

A Seat at the Table features a trove of oral histories from LGBTQ elected officials in the New York City Council and State Legislature from the 1990s to present. While there have no doubt been a number of representatives and assemblymembers who for various reasons remained in the closet during their public service, the spotlight here is on the officials who were open about their sexuality while in office. The beating heart of Gourjon-Bieltvedt and Petrus’s exhibit is turning these testimonies into a fervent call to young people for optimism and for action.

State Senator Thomas Duane. 29th Senate District (1999-2007); City Council Member, 3rd District, Mahattan (1992-1998). Photo: Veronica Luz.

I was one year old when effective protease inhibitors began to be rolled out to treat the symptoms of HIV/AIDS, eleven when Fields v. Smith enshrined the right of incarcerated trans people to access hormone therapy and surgery, and twenty-one when I attended my first queer wedding following the Obergefell v. Hodges verdict. It has been far from a linear path, but for many people my age and younger, the past decades have featured an enormous increase in visibility and significant legal wins for queer people, particularly in New York. A Seat at the Table inserts us into the lives and tactics of the city’s elected officials who made these gains possible while resisting the attitude that progress is inevitable. Rather, the team behind this exhibit alert us to the constant need to push for progress while offering a wealth of insight into how queer organizers and our allies might resist the backslide in national LGBTQ rights we find ourselves contending with.

“We cannot go back,” State Senator Tom Duane advised former Council Speaker Corey Johnson during the latter’s 2013 campaign in District 3. In return for his support, Duane asked Johnson to speak openly about both his sexuality and positive HIV status on the trail, as Duane himself had done during his successful campaign for the same seat two decades prior. Since his victory in 1991, the district has been represented by Duane, Christine Quinn, Corey Johnson, and currently Erik Bottcher — all of whom ran as openly gay and contributed oral histories to the exhibit. In his own testimony, Duane notes the importance of this continuity of representation in City Council, and in so doing provides a name for this exhibit: “There really is no substitute to a seat at the table.”

Bringing a folding chair

I confess, I am generally suspicious of the notion that political representation equals political progress or increased accountability. What the people in power identify as is not nearly as important to me as who they identify with. When I first sat down with A Seat at the Table, I noted the tension in my shoulders. I’d unconsciously put myself on the defensive, prepared for honeyed words insisting that one’s gayness or queerness marks them as inherently good for their constituents. I quickly discovered that many of the exhibit’s twenty-one featured individuals shared my skepticism. District 35 Councilmember Crystal Hudson, while praising citywide progress in LGBTQ political representation, cautions that “we have a long way to go” to ensuring the needs of queer BIPOC residents—who face far greater risk of homelessness, poverty, isolation, and sexual violence—are heard and addressed. When first elected in 2021, she, along with Kristin Richardson Jordan, became the first out queer Black women on the Council. Both represent historically Black neighborhoods where issues of LGBTQ rights are intricately interwoven with rampant gentrification and a pandemic that due to structural racism kills Black Americans at 1.4 times the rate of their white neighbors. For Hudson, a seat at the table goes beyond optics. It means upending business-as-usual in order to bring the needs of constituents who “want to see [themselves]” in the people and policy impacting their lives.

City Council Member Crystal Hudson. 35th District, Brooklyn, (2022-Present). Photo: Veronica Luz.

Hudson’s testimony calls to mind the adage “if they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair,” typically attributed to former congressional representative Shirley Chisholm. Chisholm, who like Hudson represented the neighborhood Bedford-Stuyvesant, speaks here of the table’s design as well as its occupancy—seats of power like the House of Representatives or New York City Council were not built to have women of color or queer people occupy them. When they do, those officials “have to be twice as good, they have to be better,” in order to not be written off as underqualified or single-issue politicians, as Duane puts it. Grit and determination are key, as any politician will tell you, but so is a capacity to reach, connect with, and amplify the concerns of neighbors with which one may have little in common. Once at the table, how do you work to continue dismantling barriers while also serving a diverse multitude of constituents? And how do you ensure that work carries on after you?

Gourjon-Bieltvedt and Petrus partnered with a host of collaborators at LaGuardia Community College to draw out the answers to these questions. Students including Valerie Pires and Scottie Norton conducted oral histories alongside Petrus, while Gourjon-Bieltvedt’s students contributed the exhibit’s photographs of all featured interviewees. Inviting each subject to speak on their experience coming into their sexuality or queerness, the histories then pivot to how those officials allow their identities to enrich their lives and those of their fellow residents. In one of the exhibit’s more poignant moments, former District 2 Councilmember Rosie Méndez discusses helping two elderly constituents handle a housing issue while working for her predecessor, Margarita López. Some time later, the couple returned to Méndez to thank López and her for their help. They informed her that their grandson had recently been abandoned by his parents because of his sexuality, and that because of the positive impact Méndez and López had on their lives, they decided to take him in. “Sometimes… we get to make change at a big level through legislation or funding… but sometimes we also do it on an individual level in terms of changing people’s minds and attitudes by living our truth and living who we are.” Former District 25 Councilmember and Queens Pride Parade co-founder Daniel Dromm makes a similar approach the cornerstone of his advocacy: “I always try and get people to see the intersection of sexuality and gender with race and religion.”

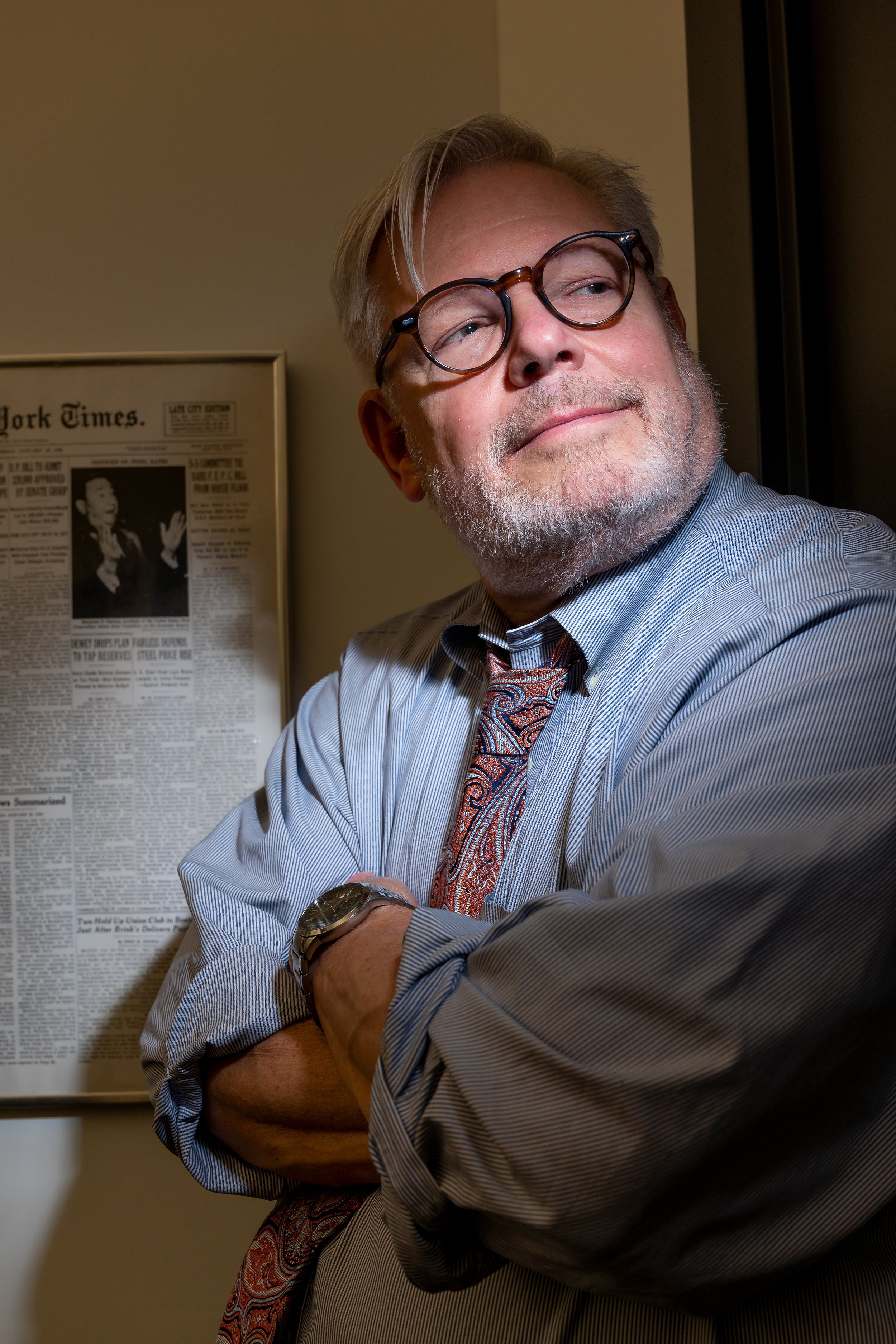

Hon. Matthew J. Titone. Surrogate’s Court Richmond County (2019-Present); State Assembly Member, District 61, Staten Island (2007-2019). Photo: Christian Garcia.

Elsewhere, the interviews bring to light how their subjects became engaged with intersectional politics because of their organizing for LGBTQ rights. Surrogate Judge Hon. Matthew J. Titone recalls first becoming active by providing pro bono legal services at Staten Island AIDS Task Force, back when the virus was implicitly associated with gay men. Titone quickly discovered, however, that the “face” of HIV/AIDS on Staten Island was far different that he’d been conditioned to assume. With the exception of four clients, all the people Titone worked with were single, straight Black women. This was a population he previously had no idea existed on Staten Island—let alone were among the highest at-risk of seroconverting by the mid-1990s. Titone’s experience inspired him to rethink his view of HIV/AIDS, as well as how he could better serve and work in coalition with his nongay neighbors. Years later as a legislator in the state assembly, Titone was instrumental in securing funding for the first women’s health delivery clinic, a Planned Parenthood, on Staten Island. When asked how to respond to people who say you cannot get elected because you are gay or trans and the area is too conservative, he had a simple answer: “Fuck you.”

Queering the table

A Seat at the Table is attuned to the small moments that transform residents into leaders. Because many of the interviews begin with stories of personal discovery or coming into oneself, they are well-suited to be shared in a variety of classroom settings, where students are often themselves navigating their identity and relationship to the communities around them. Méndez and Titone’s testimony can serve as jumping off points for fruitful conversation regarding LGBTQ identity, history, and activism, or for civic engagement more broadly. The exhibit’s comprehensive volume also allows for a rare instance of cross-generational conversation between queer organizers, with the testimony of Gen-Z Councilmember for District 36 Chi Ossé displayed alongside those of AIDS crisis-era activists. The viewer, in turn, is brought into decades of process in action, exploring how organizers, advocates, and community leaders have negotiated the tricky process of breaking electoral barriers and serving as highly visible role models while working to make an impact on the local level.

City Council Member Rosie Mendez. 2nd District, Manhattan (2006-2017). Photo: Christian Garcia.

Sometimes these relationships are direct, as in the case of López and Méndez or former District 13 Councilmember James Vacca and his protégé and successor (now U.S. representative) Ritchie Torres. More often, the tethers are unspoken. Méndez, Hudson, and López, among others, discuss the difficulty that comes with parents’ initial negative reactions to coming out, with the latter two also touching on the capacity for those same parents to evolve and become champions of their children later in life. López’s mother eventually marched with her in the Manhattan Pride Parade, and gave a speech declaring that queer people were all children of God. It was these experiences that inspired her, like several of her contemporaries in the exhibit, to combat LGBTQ youth homelessness by educating parents. Hudson, for her part made A Black Agenda for NYC a cornerstone of her candidacy, where she underlines the need to center young, unhoused Black trans women and non-binary femmes in housing initiatives. As the viewer makes their way through this web of interviews spanning over thirty years of public service, we too are called into the practice of history-making by identifying these connections across interviewees and their methods of building powerful local, municipal, and statewide coalitions.

Building impact through the archives

Petrus and Gourjon-Bieltvedt deserve particular commendation for their engagement with HIV/AIDS throughout the exhibit. Longtime activist-historians Alexandra Juhasz and Ted Kerr’s recent We Are Having This Conversation Now (2022) critiques the tendency of archives to group AIDS-related material thoughtlessly with LGBTQ collections, which reinscribes the misleading suggestion that AIDS is inherently queer into the historical record.

As we enter the fourth decade since the virus was first reported on by The New York Times in 1981, the realities of its spread have grown increasingly complex. What was once scientifically codified as queer through the name Gay Related Immune Deficiency (GRID, now HIV/AIDS) and socially codified as a white gay man’s disease in the United States is today understood to be a globally dispersed health crisis closely tied to poverty, imperialism, and racism alongside homophobia. In New York State, where the most common category of transmission for women by far is heterosexual sex, HIV is 12.7 times more prevalent among Latinx women than white women, and 21.9 times more among Black women. To accurately document HIV/AIDS in the archive requires holding multiple truths in the same hand. We need to work with intention to acknowledge the enormous role the virus had in shaping early openly lesbian and gay leaders like Deborah Glick and Duane, while recognizing its devastating impact on nongay communities, as well as the role racism has played in its continued spread. A Seat at the Table hits all these marks, bringing a nuanced approach to preserving and depicting the entwined relationship between queer political leadership and HIV/AIDS.

For those considering using A Seat at the Table in the classroom, Stephen Petrus and LAGCC professors Tara Hickman and Juline Koken have attentively crafted three accompanying curriculum units. Designed to be adaptable for high school and undergraduate students, these lesson plans delve fearlessly into topics rarely covered by even the most inclusive curricula: homelessness among LGBTQ youth, the Giuliani administration’s exclusionary zoning practices to eliminate sex work from Times Square, and LGBTQ exclusion from the St. Patrick’s Day Parade. Petrus, Hickman, and Koken’s candor is a breath of fresh air, and offers an impressive backbone for staging classroom conversations that encourage students to imagine themselves as future decision-makers.

Starting with an introduction to the subject at hand, each unit then delves into primary sources ranging from the oral histories to political cartoons to government reports. Juxtaposing material from the Giuliani administration’s efforts in Times Square against District 22 Councilmember Tiffany Cabán’s testimony in defense of decriminalizing sex work, Koken and Petrus teach how to read sources against the grain, draw their own conclusions on why policy was enacted, form their own definitions for terms like “survival sex work,” and devise their own solutions to building a more equitable justice system. Even if you are not an educator, the highly adaptable style invites the reader to build intellectual connections across thirty years of organizing, making them valuable reading for anyone interested in public LGBTQ history in New York.

A thank you to my Councilmember

City Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer. 26th District, Queens (2010-2021). Photo: Makoto Kato.

This morning, I wrote a few words from the oral history of my former Councilmember in District 26 Jimmy Van Bramer on a post-it note and stuck it inside my journal: “Queer people are beautiful. Queer love is beautiful. Queer sex is beautiful. And that is something we must never back down from.” While he was still my representative, Jimmy’s office helped me quickly secure stable housing in the midst of the early pandemic. I’d expected an automated reply, but instead received a thorough list of resources and several follow-ups ensuring I had a roof over my head. I joked with friends that Jimmy must have recognized a fellow queer person and known that we take care of our own. As I reflect on the many stories on display in A Seat at the Table, I suspect there may be more truth to that than I realized at the time. Gourjon-Bieltvedt and Petrus don’t promise that the future will be bright or that the path forward for LGBTQ rights will be easy. But their work affirms that there is power in memory and in optimism— and a desperate need for both in order to respond to the present moment. Particularly for young trans people who are being exposed to intense scrutiny and adversity by entrenched, emboldened bigotry, we must model how we care for one another and how we resist those who would wind the clock back on the advancements of the past three decades. A Seat at the Table offers a roadmap to both while providing a timely reminder that there is much good work to be done on the ballot, in the school, and in the streets.

Dani Stompor (they/them) is a graduate student in the Library Science and History programs at Queens College, CUNY. Their primary areas of research include the history of HIV/AIDS, LGBTQ activism in New York, and archival practices of care.