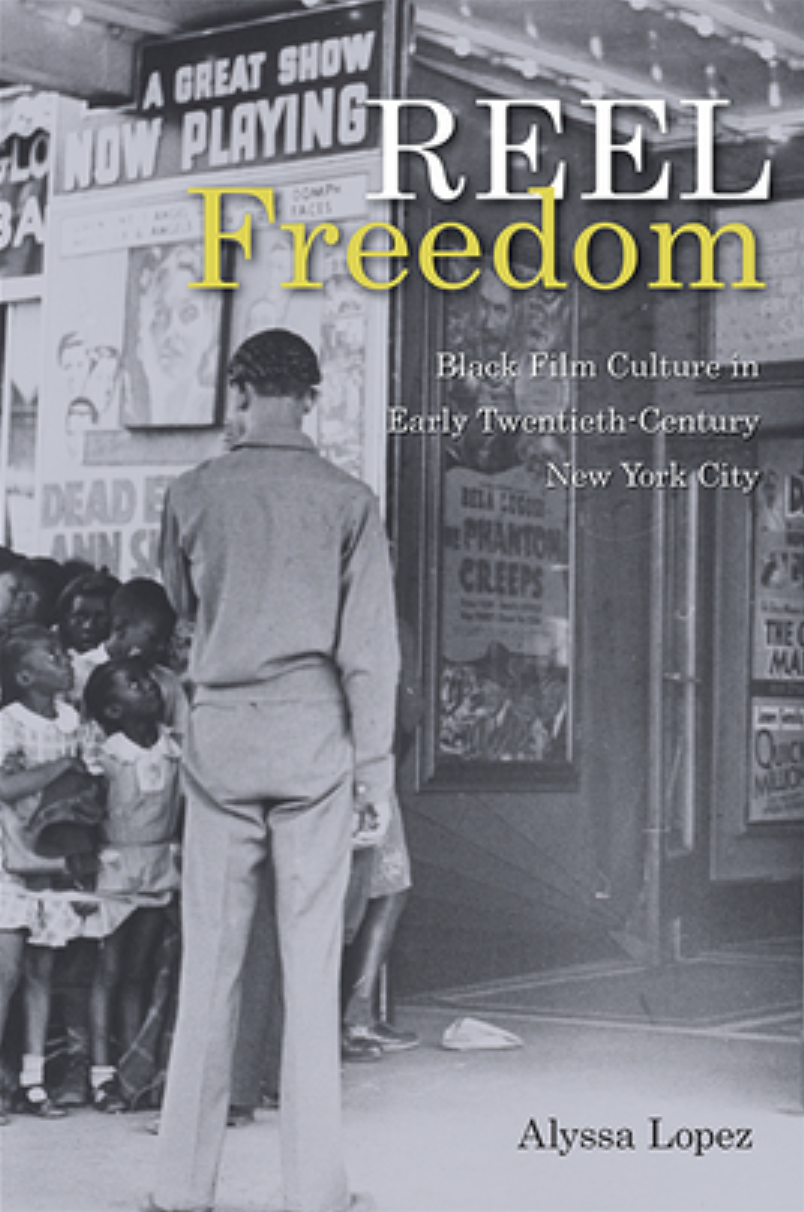

Alyssa Lopez, Reel Freedom: Black Film Culture in Early Twentieth Century New York City

Reviewed By Deena Ecker

Popular culture and entertainment are key pieces to understanding the Black struggle for rights and freedom. Through engagement with entertainment, Black people assert their right to occupy space, work in entertainment jobs, and enjoy the amusement that popular culture provides. Alyssa Lopez pulls together the threads of film, place, community, labor, and the fight for racial equality in her exemplary new book Reel Freedom: Black Film Culture in Early Twentieth-Century New York City. By focusing on film in New York City, Lopez is able to look at how members of the Black community at the start of the Great Migration made a home in the city beyond where they lived and worked, but also in how they spent their leisure times – at the movies. She argues that Black film culture was deeply and inextricably intertwined with Black Americans “demands for equality and claims to city space. [pg. 3]

Lopez’s definition of Black film culture is multifaceted. While it included movies created by Black writers, producers, directors, and actors, that is only one of many important pieces of Black film culture. Just as significant were where and how Black people consumed movies, contestations over space in the theaters, the labor of Black projectionists, and the community that developed around film. Lopez explores each of these elements of Black film culture in depth within her book.

Reel Freedom challenges the reader to think beyond the Harlem Renaissance and place film, an important piece of leisure in the 1920s and ‘30s, at the center of the Black cultural and intellectual transformation in New York and the nation. While much of the book focuses on the theaters in Harlem, Lopez reminds us that in the first decade of the 20th century, there were pockets of Black life all over the city. The ways that Black moviegoers, critics, projectionists, and producers engaged with film demonstrated a claim to physical, intellectual, and cultural space in early-twentieth-century New York. In real and significant ways, these claims to space were part of the larger Black struggle for equality.

Each of the five chapters takes on a different element of Black film culture: community engagement, inside the theaters in Harlem, the battle between the New York State Motion Picture Commission and Black filmmakers (particularly Oscar Micheaux), Black projectionists labor organization, and the film critics in New York’s Black press. Each of these chapters explores the tensions within the Black community about what the movie-going experience should be as well as the ways that Black people used the movies as a site of resistance against the many forms of white supremacy Black people had to contend with.

Chapter one looks at the ways Black people went to the movies. In a creative use of source-work to fill in the negative space, Lopez finds the evidence of Black movie-going in the discourse around film. Lopez asserts that the ways that the press, preachers, and advertisements talk about film are evidence to the centrality of the movies to Black life. The Black community turned the movie-going experience into one that combined entertainment with religion, mutual aid, and community building. Churches showed movies (sometimes with a “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” attitude), parks screened films as part of larger events like picnics, and theaters themselves put on mutual aid events for the larger community. Black film culture combined with Black business practices to enhance both. This chapter also looks at who owned and managed the theaters in Harlem, and the racial contestations surrounding theater ownership and management.

We go into the physical space of the theaters in chapter two, when Lopez explores the movies, and particularly the darkness in the theaters, as a site of sexual transgression and crime (both real and imagined) as well as entertainment. Lopez zooms in on the experiences of Black girls and women, who went to the movies to escape — both the crowded spaces where they lived and worked and the oppressive nature of being Black and female. Black girls and women internalized the racial geography of amusement — knowing where they would be welcome or safe and where they would not — and moved about the city and to the theaters with that knowledge. While there was pressure from families and reformers for Black girls to remain “pure,” they themselves often chose freedom of movement and prioritized their own amusement.

We move from the physical spaces of the theaters to the other side of the camera in chapter three, which highlights the struggles between Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux and the New York state censors. Censorship largely fell to white women who valued sexual purity and white supremacy, and rejected violence in film. The ways that Micheaux battled the Motion Picture Commission usually had to do with racial and sexual content. Lopez argues that Micheaux learned over time how to craft films that could get past the censors by learning their preferences. However, at times Micheaux either ignored the censors or found ways to show his films without the proper license in order to maintain the messages he wanted to get across and the stories he wanted to tell.

In a crafty melding of labor history with film history, chapter four explores the battles that the Black film projectionists had over fair wages, hours, and safe working conditions. These struggles were both with the theater owners and managers as well as with the white-led unions that maintained a segregated membership (except where it served their own purposes to allow Black members). Despite theater owners’ assertions that it was unskilled work that anyone could do, becoming a film projectionists required training and certification. Lopez expertly draws out the ways that Black projectionists navigated multiple identities. They fought the segregated union in order to gain their own membership. Once they achieved that membership, Black projectionists sided with the union in its strikes to fight for better condition for the white projectionists in the city, even when it went against the Black projectionists’ own self-interest. This chapter demonstrates the intertwined relationship between race, place, labor, and cinema and shines a light on the labor side of Black film culture.

The final chapter of the book explores the discourse around cinema in the Black press, highlighting the writings of two film critics for the New York Age — Lester Walton and Vere E. Johns. By looking at these writings, Lopez uncovers the ways that Black critics understood the racism embedded in film, the ways the Black community reacted to segregated theaters, and the ideals that the Black elites wished to impart upon the wider Black community. By looking at the film critics, Lopez makes abundantly clear that racial violence cannot be disentangled from entertainment generally, and cinema in particular. Walton argued that the advertisements for racially violent films that could be found outside the theaters around the city constituted racial violence in and of themselves — reminding Black people that they were not safe and bringing the extreme violence of the South into their Northern home. Both Walton and Johns believed the content of the films fostered the belief that racial violence was socially acceptable to white northerners, making the Black community less safe and causing instances of racial violence in New York. Walton also took on segregated in seating in the theaters and, by highlighting the respectability of Black patrons, asserted Black people’s right to enjoy the movies from whatever seat they chose. Johns advocated for boycotting movies that perpetuated racist stereotypes and did not employ Black performers in meaningful roles. Johns thought that digging into the bottom line of the studios was the only way to make the message heard.

As Lopez states, “Black film culture was an important avenue of both entertainment and resistance for Black New Yorkers: a critical site of interaction with the cultural phenomenon and a battleground to stridently fight for their right to belong to the city.” [pg. 4] This book effectively demonstrates how these processes took place both by the producers of culture like Oscar, Lester Walton, and Vere E. Johns and the Black community who went to the movies and worked in the theaters. Throughout the book, Lopez shows the ways that New York City is a key place to study and understand Black film culture. The thriving Black press, the intellectual and labor sides of the New Negro Movement, and the robust and diverse Black community in New York all make it a fascinating place to explore the themes of Black film culture, race and entertainment, leisure, and urban space.

Deena Ecker is a PhD Candidate in history at the Graduate Center, CUNY, and former Managing Editor of Gotham. Her research focuses on the pleasure and leisure economies of New York City in the early-20th century.