Melting Metropolis: An Interview with Daniel Cumming and Kara Murphy Schlichting

Interviewed By Rachel Pitkin

In honor of Climate Week — an annual event that aligns with the United Nations General Assembly and is run in coordination with the United Nations and the City of New York — Rachel Pitkin talks to Daniel Cumming and Kara Murphy Schlichting, researchers on “Melting Metropolis: Everyday Histories of Health and Heat in London, New York, and Paris since 1945.” Based at the University of Liverpool, UK, and Queens College, CUNY, Melting Metropolis is a Wellcome-funded project exploring how Londoners, New Yorkers and Parisians have thought and felt about heat and its impact on their health. In partnership with the technology nonprofit Urban Archive and Queens Memory Project, Melting Metropolis ran an open call for old photographs and personal histories that illustrate how New Yorkers have experienced the everyday heat of summer. You can catch the Melting Metropolis team at the American Museum of Natural History “Climate Resilience in Action” event Thursday, September 25, 2025, starting at 6:30 PM, as part of NYC Climate Week 2025.

Susan C. Ryan, Rockaway Beach, Queens, July 4, 2012.

RP What is your collaborative project Melting Metropolis all about?

KS: Melting Metropolis brings together a team of nine scholars from history, ethnography, and geography, a community engagement manager, and a research artist to investigate how, in the past (as in the present), summer weather and long-term climate-based challenges were unevenly distributed across London, New York and Paris. With a focus on sensory, community, and cultural experiences in these three cities since the postwar era, we investigate how city dwellers have both enjoyed summer heat and sought to mitigate its negative impacts, particularly as it relates to human bodies and environmental health.

We helm Melting Metropolis's New York City case study. New York’s climate delivers summers that are hot and humid, and heat waves magnify the season’s environmental challenges. And New Yorkers have, since the 1790s at least, known that their city had an additional environmental challenge in summer: the urban heat island (UHI) effect (the phenomenon of warmer temperatures in urban developed areas). The effect is particularly pronounced in densely built areas with limited green space and high concentrations of heat-absorbing surfaces.

DC: While all bodies process heat in the same way, not all New Yorkers faced the same summertime heat exposure. It varied by building, by block, and by neighborhood. New York's built environment created the UHI, while class and racial segregation magnified residents' vulnerability to heat. The city's geography of thermal inequality became particularly extreme in some districts through government disinvestment, impoverishment, and housing deterioration, which together, heightened poor New Yorkers' exposure to the UHI. As a result, low-income communities of color bear a disproportionate heat burden in neighborhoods long undermined by environmental injustice. And heat exposure is a growing public health problem today: heat-related illness kills over 500 New Yorkers each summer, and Black New Yorkers are more than twice as likely to die from heat than white New Yorkers. [1] In fact, heat kills more people every year across the US than all other natural disasters combined. We have gotten somewhat used to 17-20 days of extreme heat each summer (defined as temperatures over 90 degrees), but a recent report from the New York City Panel on Climate Change projects that in the next 25 years the city is likely to experience between 32 and 69 days of extreme heat each year. Without mitigative policy intervention, in the worst-case scenario, we could see as many as 108 days by 2080. [2]

Yet heat-related health risks are only one aspect of urbanites’ relationship with heat in their cities. Hot summer days also herald opportunities such as summer festivals or swimming outdoors. The social history of summer shows that New Yorkers have long practiced local traditions of heat mitigation. These traditions reveal that beating the heat was often a source of pleasure and community even when heat itself was also a source of discomfort, even danger.

RP: What are the pros and cons of visual archives when it comes to studying summer heat?

KS: Searching for archival evidence of the link between the body, health, sensorial experience, and built and natural environments has a number of challenges. The first challenge is that experiences of heat and humidity are of course inherently personal and subjective. The second challenge is that historic summer heat is difficult to reconstruct archivally. No standard scientific definition of a heat wave exists. And heat recording technologies have changed over time — it is difficult, and largely foolish, to try to compare baseline temperatures across time. The third challenge is the difference between bodily experiences and meteorological records. Official weather data does not necessarily offer a full accounting of New Yorkers’ experiences of heat. Since the late nineteenth century, residents have known official records were different from bodily experiences of high temperatures, especially within the uneven geography of the urban heat island.

Visual archives offer one final challenge to hot weather research, but also a solution. Heat is a difficult type of weather to find in visual archives. Weather in general is a temporally shifting and often intangible category of nature. And heat is especially tricky, since it is invisible. Snow or rain, for example, are easier to find in a visual archive. Visual archives have proven to be full of examples of how New Yorkers have lived with summer heat. The solution to the challenges of studying extreme heat has been to look for the social history of summer in the city.

RP: Tell me more about the work you are collaborating with Urban Archive on this summer.

DC: This is our second summer collaborating with Urban Archive. A few months ago, we launched our second open call for old photographs and personal histories that illustrate how New Yorkers have experienced the everyday heat of summer. This year we are looking for photos of how people cooled off across the five boroughs. So, dig into your personal collections and find those images that capture the essence of a New York summer! Each photo must include at least one human subject and a brief description. We have also built thematic stories from photographs already digitized and available on Urban Archive. Based on last year’s photos, we created two stories: shade and water. This year’s open call submissions will dictate what our next thematic story will be.

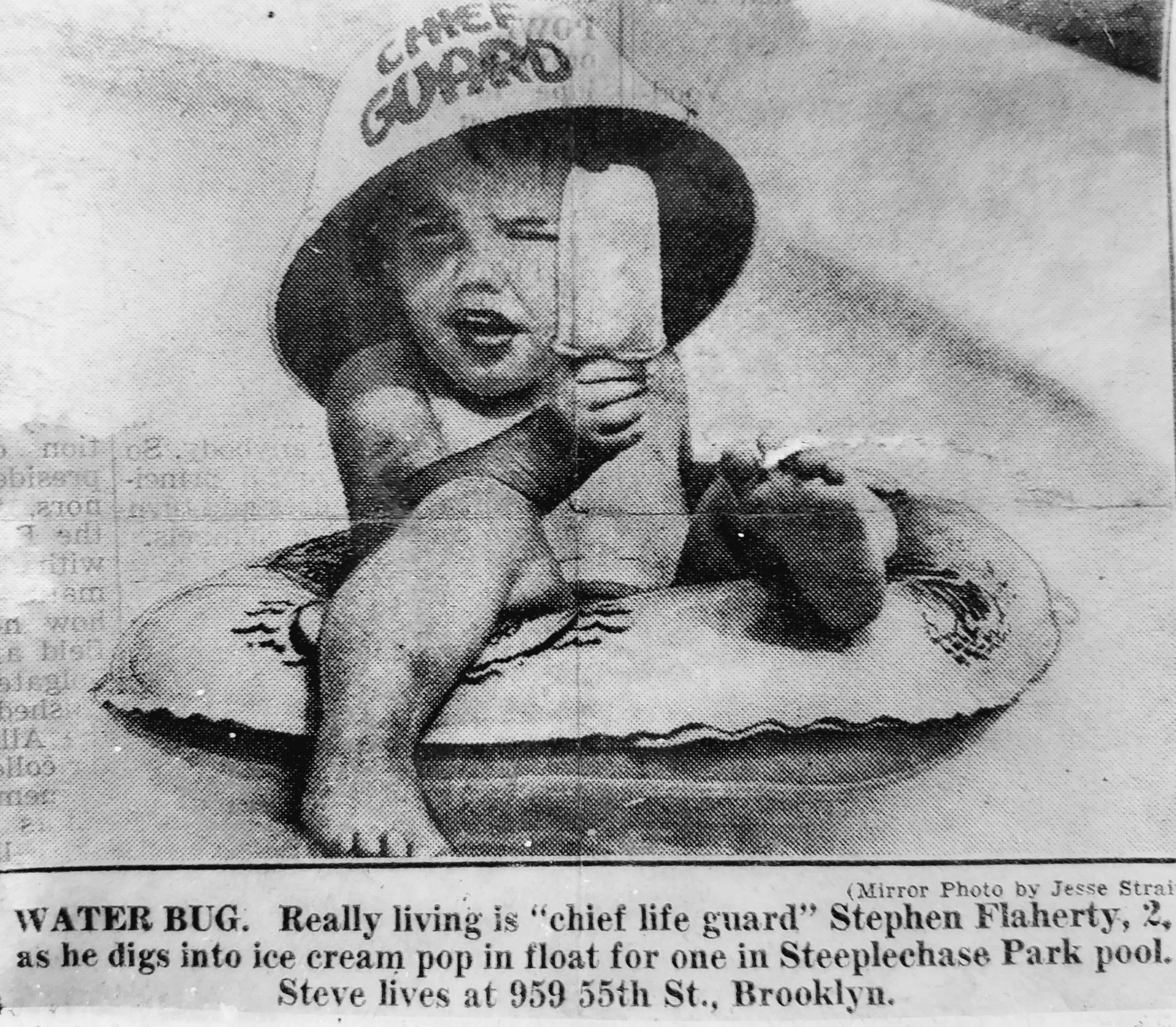

A cool treat at Coney Island has long been a summer joy. Top: This submission to Melting Metropolis + Urban Archive’s Summer 2025 call was published by the New York Daily Mirror in 1953. Submitted by Stephen Flaherty (pictured!). Bottom: Orlando Mendez, Coney Island, July 2017.

RP: How do public archives and visual records help communicate the idea of summertime heat as a shared experience for everyone while also highlighting the uneven nature of that experience?

DC: So many of the photos submitted communicate the joys of summer and the many ways people have created a shared culture in navigating the city’s infamously high temperatures and — at times — oppressive humidity. It wouldn’t be New York City, after all, without familiar experiences of escaping to beaches, parks, pools, or shady blocks while feeling like you might wilt in place if left surrounded by the city’s dense concrete, tall skyscrapers, and hot blasts of subway air.

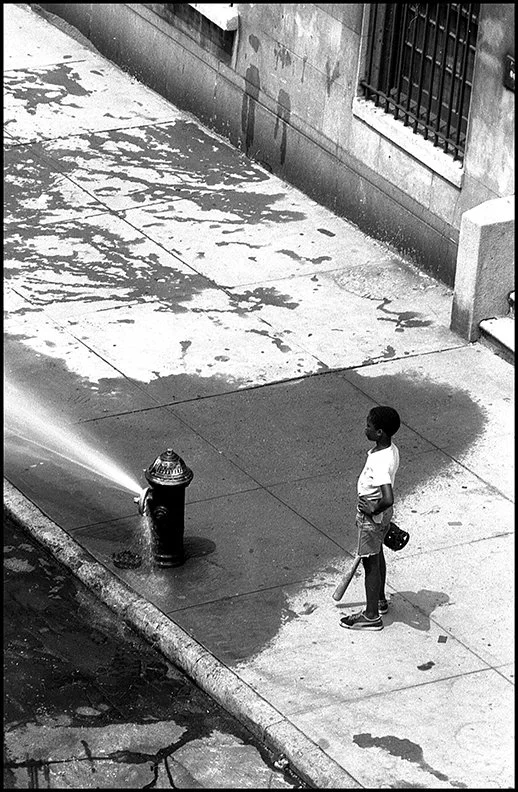

The open fire hydrant is an icon of city summers. Top: This photograph captures a young man, hot from a baseball game in Riverside Park, stopping to enjoy the cool water of an open hydrant. Drew Carolan, UWS, Manhattan [W. 88th St. on the UWS], July 1975. Bottom: Nadira Gupta Brooklyn [Bedford-Stuyvesant], 2025. This photo captures a hot day in summer 2025. The photographer reflected on the kinship the open hydrant offered passerby. Strangers cooled off together, “connecting and commiserating over the scorching heat while enjoying the cool refreshing water.”

It’s important to keep in mind, however, that not everyone experiences hot summers the same way. The NYC Department of Health’s “Heat Vulnerability Index,” highlights how heat has become a magnifying glass that exacerbates the city’s pre-existing conditions of social inequality, particularly along lines of race and class. This vulnerability, moreover, extends beyond where people live. For residents working outdoors in exposed industries such as construction, landscaping, transportation, delivery, and street vending, urban heat can be a miserable and dangerous workplace condition that requires careful strategies to survive the summer months. Legislation proposed at state and city levels is beginning to take these challenges seriously, while unions that represent outdoor workers are fighting for rights to heat relief in their bargaining contracts. [3] Some of the most hazardous conditions, however, are experienced by New Yorkers in city jails and state prisons, where heat-mitigation policies, and their limitations, can quickly become an issue of life or death. [4] In the city’s older neighborhoods, racial discrimination in housing coupled with decades of disinvestment, even recent predatory lending, continue to undermine residents’ efforts to build environmental resiliency into their neighborhoods, whether it be pools, parks, shade, weatherized buildings, or consistent energy services. Among elderly residents in low-income neighborhoods, those most vulnerable to heat, air conditioning units are less ubiquitous than they are in wealthier locales. High electricity bills force many residents into a financial predicament weighing the costs versus benefits of air conditioning that can limit their use to dangerous levels during the summer. [5]

KS: Public archives help create a record that highlights, or at least can suggest, the varied experiences of summer heat, even if one must learn to “read” the images with a critical eye. And while the archive itself is inherently selective — not everyone can or will upload their images of summer, of course — visual records that cross all five boroughs and span multiple generations reveal a rich tapestry of New York City life over many summer seasons.

RP: Public Engagement is a key component of MM. Can you explain your research team's approach to public engagement and public history?

DC: We built this team with interdisciplinary collaboration as a core feature. Public engagement is one of three pillars in the project (the other two being community engagement and academic production), and it represents our commitment to communicating our findings with as many members of the public as possible. Each member of the team, from artist to scholar to curator to researcher, has a role to play in distilling their expertise into the medium best fit for public consumption and interpretation. This looks like environmental walkshops on “drawing heat” where historians and artists lead members of the public on city tours that blend urban study with artistic inquiry; a partnership with New York Public Schools that will produce K-12 curriculum on histories of the urban heat island and climate change; supporting our research artist in creating sculpture and dance installations on heat as an embodied ecology; and writing for public readership though op-eds and public-facing blogs (hello, Gotham Center!). At the same time, true public engagement is not a unidirectional relationship. We continue to learn from our partners and audiences in unexpected ways, which then reshapes our research questions and even methods of interpretation. This mutual exchange leads to a greater understanding of our project’s most central concerns, and most importantly, creates a shared experience among the many contributors who all have a hand in producing not just what we know about urban heat, but how we know it too.

Our commitment and methods of public engagement also apply to the other public-oriented pillar of the project: community engagement. Though similar, the distinction between the two is important regarding audiences reached and the processes of production, from beginning to end. We work closely with neighborhood organizations, nonprofit institutions, and longtime residents interested in telling their own stories about how heat and summer have shaped their communities. This method of community-engaged research is intentional about building partnerships, collaborating on decision-making, inverting power dynamics in research production, ensuring relevancy in people’s lives, and establishing mutual ownership over the final products. Currently, we are conducting oral histories with residents and community organizations, partnering with Newtown Creek Alliance (Brooklyn) and King Manor (Jamaica) in a local Storyteller Program, and working closely with Queens Memory Project of Queens Public Library, which is the official repository of the interviews and materials produced.

When the city heats up, New Yorkers extemporize new places and ways to cool off. Top: Thomas Comiskey, East 16th Street and Avenue C next to the East River Drive, 1970s. This photograph captures one such approach: “On hot days, my Stuyvesant Town friends and I would fill up a cooler, cross Avenue C to the benches on the East River Drive walkway, and listen to tunes while watching the seaplanes land at 23rd Street.” Bottom: Tee shirts become hats and young men bare skin to (hopefully) cool off with rooftop breezes in lower Manhattan. Andrew Kass, Church and Chambers roof, with spencer & jack, circa 2014-2016.

RP: What is the value of public engagement work when it comes to the history of climate change?

KS: The visual archive that we’ve built over the last two summers with Urban Archive complements much of this work, highlighting both change and consistency of summer as a social experience over time. As we’re all increasingly aware, our summers are becoming hotter every year, and heat waves are increasing in intensity and duration. Our visual archive coupled with our public and community engagement strategies help communicate the importance, even urgency, of urban heat as our cities and planet warm at an alarming rate.

Narrating the history and contemporary experiences of heat from the bottom up, while linking its layered dimensions to policy formation at local and state levels, Melting Metropolis aims to contribute to the efforts of our many different partners who have become part of the project. At the same time, we hope our work adds to a much larger conversation on climate change that avoids the pitfalls of alarmism while taking a clear-eyed perspective on the necessity of collective action toward resiliency and mitigation strategies regarding extreme heat as it exists today. Without strategic and informed intervention, urban heat will compound into an increasingly dangerous threat, and as a silent killer becoming more visible every summer, exact devastating tolls in our near and long-term futures.

DC: We look forward to sharing the results of the 2025 Melting Metropolis + Urban Archive “Summer in the City” open call for photographs. So far, we have had over 70 submissions, and they are uniformly wonderful—all the visuals in this conversation draw from these submissions. While summer 2025 is officially over, we would still love to hear from more New Yorkers. We hope people will be inspired to submit to the visual archive, and to think about the ways that environmental inequalities in the city, when it comes to heat, are never just a story of "risk" or "vulnerability," but there is community joy, connection, and creativity inherent to how New Yorkers, past and present, respond to extreme heat.

Daniel Cumming, PhD, is a historian of the 20th century US. He is a member of the Queens College History Department and a Postdoctoral Research Associate on the Wellcome Discovery Award project “Melting Metropolis: Everyday Histories of Health and Heat in London, New York, and Paris since 1945,” which explores the impact of climate change and rising temperatures on urban life.

Kara Murphy Schlichting, PhD, is an Associate Professor of History at Queens College, CUNY and the CUNY Graduate Center. A historian of New York City and the urban environment, she is a co-investigator on Melting Metropolis.

Rachel Pitkin is a PhD Student in American History at the CUNY Graduate Center and Managing Editor of Gotham: A Blog for Scholars of New York City History.

[1] New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, “2025 NYC Heat-Related Mortality Report” (2025) at https://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/data-features/heat-report/.

[2] Christian Braneon et al, “NPCC4: New York City climate risk information 2022—observations and projections,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1539, iss. 1 (2024):13–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.15116.

[3] NYC Comptroller, “Safeguarding Outdoor Workers in a Changing Climate” (September 2024) at https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/safeguarding-outdoor-workers-in-a-changing-climate/; Clarify News, “Hot on the Job: How Should New York Protect Workers from Heat?” City Limits (September 11, 2023) at https://citylimits.org/hot-on-the-job-how-should-new-york-protect-workers-from-heat/.

[4] NYC Board of Correction, “Heat Mitigation Efforts in NYC Jails: NYC Board of Correction Analysis of Summer 2024 Data” (December 2024) at https://www.nyc.gov/site/boc/reports/board-of-correction-reports.page; Chris Gelardi, “Summers Are Brutal in New York’s Prisons. This Year Is Worse than Ever.” New York Focus (August 4, 2025) at https://nysfocus.com/2025/08/04/summer-heat-prisons-doccs-new-york-climate-change.

[5] NYC Comptroller, “Record Highs: Tackling Energy Insecurity in the Heat of the Climate Crisis” (June 2025) at https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/new-comptroller-report-rising-heat-kills-hundreds-of-new-yorkers-every-summer-while-energy-costs-surge/; Hilary Howard, “New York City Bill Would Mandate Air-Conditioning for Tenants,” New York Times (July 17, 2024) at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/17/nyregion/new-york-city-air-conditioners.html.