Men at Work: A New Look at the Central Park Gates

By Sara Cedar Miller

Historian Emerita, Central Park Conservancy

Figure 1. “Amerigo Vespucci (Italy) in New York Harbor during OpSail 76,” Marc Rochkind, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Pass through any of Central Park's twenty original entrances today (Figure 1), and you're walking through spaces defined more by absence than presence. These "gates" are really just gaps in the perimeter wall, full of intention never realized — invisible stories of artistic talent, social connection, and personal ambition in antebellum New York.

Like the carefully framed views created by Central Park’s designers Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, they offer at its threshold a glimpse into unseen forces that shaped America's first great public space.

Securing Central Park at night was a priority. There was much debate about the perimeter wall’s material and design, but one thing was clear: the Park needed protective barriers. They would serve to close it off at midnight and safeguard it from potential intruders who might commit crimes or acts of vandalism under the cover of darkness when the Park's gatekeepers, stationed at every entrance, were off duty. [1]

To oversee the design of the wall, the gates, and several prestigious, lucrative artworks and architectural projects, the board established a three-man Standing Committee in the spring of 1860. Two of the commissioners — the wealthy bankers Henry G. Stebbins and Charles H. Russell — became its longest tenured members. [2] They would exert considerable influence in determining who won commissions for Park projects.

In January 1862, the committee was tasked with developing a system of meaningful names that would then suggest “artistic decoration of a really high character at all the various entrances.” [3] In April, they presented a “Report on Nomenclature of the Gates of the Park” to the board, authored by Stebbins, their chairman. [4] One of the committee’s goals was to find a unifying theme, which discouraged visitors from using the city’s "monotonous numerical system," e.g., Sixtieth Street and Fifth Avenue, as references to the street grid that focused more on the surrounding city than on the Park’s pastoral setting, against the designers’ intentions. [5]

According to the report, the initial suggestions ranged from naming the entrances after states of the Union, important cities, or prominent men. But the committee chose instead to honor the vocations and demographic groups which had made New York a wealthy, productive city. As they explained, the Park’s “paramount” aim was “to offer facilities for a daily enjoyment of life to the industrious thousands who are working steadily and conscientiously.” It was “constructed with no idea of encouraging habits of laziness, or in any way for the benefit of idlers or drones.” [6]

The Protestant work ethic that shaped America’s antebellum North deeply influenced its business, civic, and moral leaders, and the Central Park commissioners were no exception. Rooted in the teachings of Calvin and the Protestant Reformation, this ethic celebrated work as the ultimate expression of one’s secular life and moral obligation. [7] For the commissioners, a visit to the Park was seen as a form of “innocent recreation” after a day of work. They captured this philosophy in their maxims: “Pleasure with Business” or “Beauty with Duty,” embodying the belief that leisure was not just a luxury, but a rightful companion to labor. [8]

The four southern entrances along Fifty-ninth Street were designed to welcome all workers, grouped into four major categories. Scholars’ Gate at Fifth Avenue celebrated all thought leaders: writers, lawyers, statesmen, physicians and educators. Artists’ Gate at Sixth Avenue paid homage to creators of the visual and performing arts. Artizans’ Gate at Seventh Avenue (later modernized to Artisans’ Gate) honored skilled craftsmen and unskilled laborers, while Merchants’ Gate at Eighth Avenue (now Central Park West) acknowledged those in the world of commerce.

Ten gates paid tribute to both past and present professions: Engineers, Farmers, Hunters, Inventors, Mariners, Miners, Pioneers, Woodman, and Warriors (those serving in the military). All Saints Gate commemorated the “holy men of all ages” who shaped “public morals” and “private character.” Women were acknowledged for their achievements in many professional fields but especially for their “all-important services… in their domestic capacity… as maids, wives, and mothers.” Strangers’ Gate honored the “intelligent and industrious travelers from other countries” who helped to remove “unworthy prejudices.” Lastly, three gates celebrated the future workforce: Children’s, Boys’, and Girls’ Gates. [9]

While the report didn't specify any inspiration for its chosen theme, the work of two sculptors working in Rome likely influenced the committee’s decision: Thomas Crawford, considered the dean of American sculpture at this time, and Henry’s sister Emma Stebbins. Rome had been the epicenter of neoclassical art since the mid-eighteenth century, fueled by a renewed appreciation for ancient sculpture. By the 1820s, the Eternal City drew American sculptors of both genders who sought to study under European neoclassical masters like Italy’s Rinaldo Rinaldi, England's John Gibson and Denmark's Bertel Thorvaldsen.

Crawford, a student of Thorvaldsen, received a prestigious commission in 1853 to design the pediment of the Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol. Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, Supervising Engineer of the Capitol Extension, conceived of its theme, The Progress of Civilization, framed “as the conquest of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant over Indigenous society in North America.”

Meigs wanted the pediment to rival the Parthenon. But he felt the ancient or neoclassical themes and figures that appealed to upper class Americans on the Grand Tour, were “too refined and intricate” for “the less refined multitude” who would view the Capitol sculptures. Crawford agreed. He wrote to Meigs, “[t]he darkness of allegory must give place to common sense,” and engage the public through what “they love and understand.” [10]

Figure 2. Thomas Crawford, The Progress of Civilization (detail), United States Capitol, Library of Congress.

On the right side of the sculpted area inside the pediment, Crawford carved a mournful Indian chief, grieving his people’s fate. He is flanked by his son, depicted as a hunter with his dog, and his wife cradling an infant. A burial mound lay at her feet, a symbol of their dying civilization (Figure 2). [11]

At the apex, Crawford placed a classically robed America, flanked by an eagle and rising sun. She looks heavenward while gesturing toward both God and what Crawford described as a "pioneer" and "backwoodsman" felling a tree. Crawford broke new ground as the first American artist to depict ordinary laborers in a major commission. His woodman, wearing contemporary clothing rather than neoclassical drapery, represented a bold departure from convention. In 1857, The Crayon praised Crawford for successfully handling what was then considered the "embarrassing details of modern dress." [12]

To America’s right, Crawford highlighted six American workers, shown with the attributes of their profession: a Revolutionary War soldier, a merchant, two school boys, and a teacher and his pupil. Lastly, a mechanic is depicted in rolled up shirt sleeves. Holding a hammer in his hand, he reclines on his cogwheel.

In 1855 the plaster models were sent to Washington and by June 1859 they were put on display in the Old House chamber. By 1863, the completed marble pieces were finally placed on the Capitol. [13] But Thomas Crawford never lived to see his figures in place. He died in 1857 at age forty-three from complications of a tumor behind his eye, a condition which had plagued him for the last two years of his life

Henry Stebbins most likely learned about the Crawford figures from his sister Emma who lived and worked in Rome, or he could have seen the models displayed in Washington. But even if Stebbins and his colleagues had no knowledge of the Crawford statues prior to 1860, they definitely learned about them when his widow, Louisa Ward Crawford, donated the sculptor’s plaster models and artworks to Central Park. For a relatively small outlay of just over $3,000, the commissioners took the opportunity to transform the existing chapel of the Sisters Charity of Mount Saint Vincent, adjacent to the northern border of the Park, into a museum of first-class artworks by a celebrated American. [14]

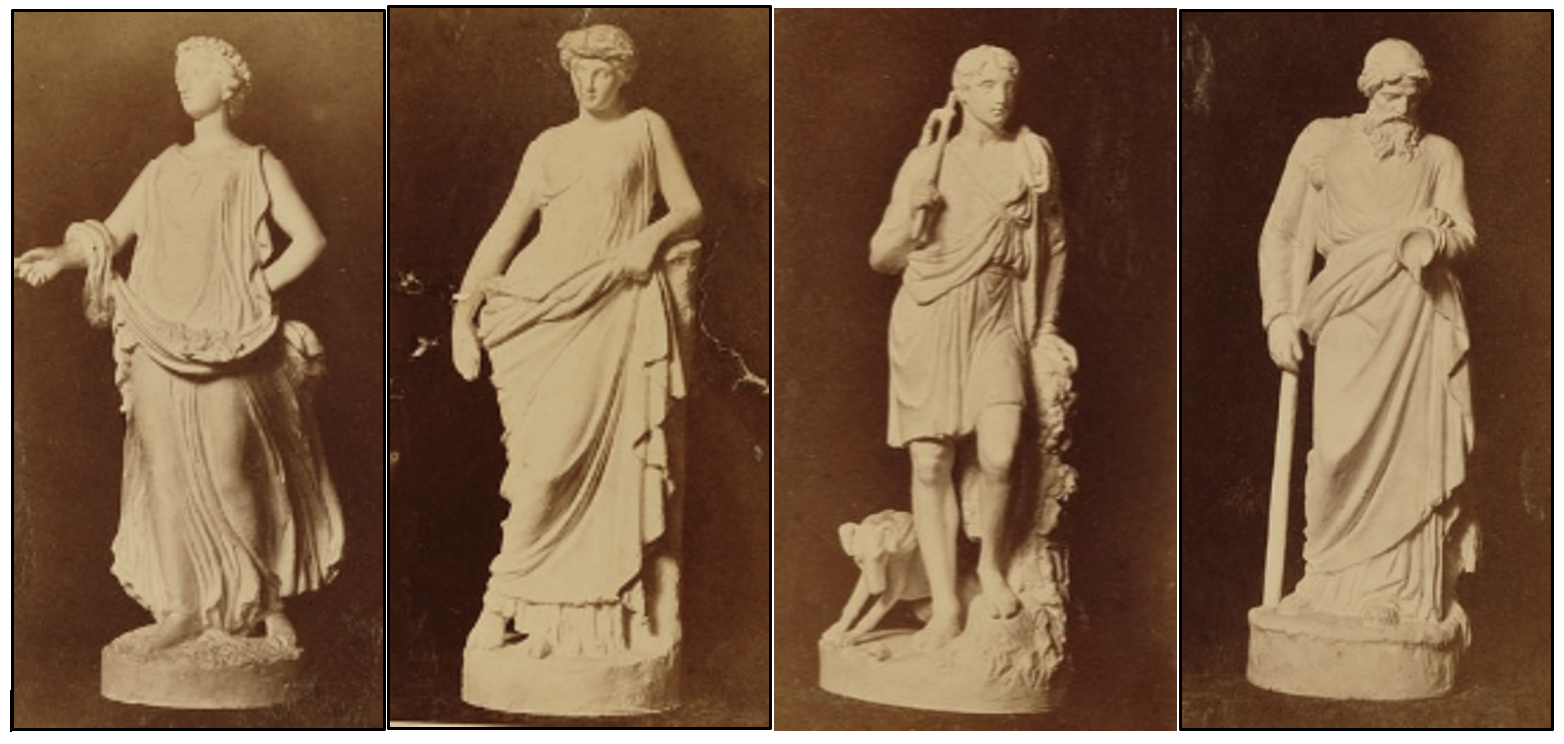

In the Fifth Annual Report, the commissioners confirmed the arrival of eighty-seven sculptures and drawings by Crawford on October 18, 1860. The gift included eleven of the Capitol figures as well as the artist’s rendering of the pediment ensemble. Two years later, seven of Crawford’s figures influenced eight of the named gates: The Mechanic (Artisans’ Gate), The Schoolmaster and The Boys (Scholars’ Gate and Boys’ Gate), The Merchant (Merchants’ Gate), The Soldier (Warriors’ Gate), The Backwoodsman/Pioneer (Woodman’s Gate and Pioneers’ Gate) and the Indian Hunter (Hunters’ Gate). Also included in Louisa Crawford’s gift were the figures of the Indian Chief, the Indian Woman, America, and the Indian Grave. The statues were photographed in the new Park museum (Figure 3) sometime before 1870. In 1881, the building burned down and all of Crawford’s plaster figures were destroyed. [15]

Figure 3. The plaster models of Thomas Crawford in the former chapel of the Sisters of Charity of Mount St. Vincent in Central Park, ca.1870, Library of Congress.

Two sculptures by Emma Stebbins, Industry (also known as Miner) (Figure 4) and Commerce (also known as Sailor) (Figure 5), influenced the vocational theme in general and two of the gates specifically. In the 1863 nomenclature report Henry Stebbins boldly referenced his sister’s figures. Without naming the artists outright, he suggested that “the artistic adaptability of the naming system has already worthy types of the Miner, the Trapper, and the Sailor, are now in existence, that have been conceived by American artists.” [16]

By controlling the naming system for the gates, Stebbins saw the potential for future commissions for his sister and ensured that both Mariners’ Gate and Miners’ Gate became two of the twenty gates for Central Park. Neither profession was featured in Crawford’s Capitol grouping.

Emma Stebbins received the commission for the Sailor and Miner from Charles August Heckscher, a wealthy coal and shipping magnate — and likely one of Henry’s social or business connections. Heckscher commissioned two sculptures to celebrate the industries — mining and navigation — that built his fortune. The sculptures were completed in 1860, and now in the collection of the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4. Emma Stebbins (American, 1815–1882), Industry (also known as Miner), 1860. Marble, 28-7/8 x 10 x 10-1/2 in. The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY, Gift of Philip M. Lydig III, 1959.354.

Figure 5. Emma Stebbins (American, 1815–1882), Commerce (also known as Sailor), 1860. Marble, 28-7/8 x 10-1/2 x 11 in. The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY, Gift of Philip M. Lydig III, 1959.355.

When composing her Heckscher figures Stebbins looked to the ancient figures of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros and Praxiteles’s Satyr. [17] But they marked a striking departure from the flowing robes and togas of her other artworks. Instead, her workers were clothed in the contemporary attire of their trades, a bold and radical shift likely influenced by Crawford’s innovative Capitol figures. When the Heckscher statues made their public debut at a prestigious New York art gallery, one critic admired the figures for their “honest” and “fearless” “spirit of American labor,” but tempered the praise with “[m]odern in face as in costume though they be…” [18]

Central Park's designers created an experience of changing scenery that Frederick Law Olmsted referred to as a “gallery of mental pictures.” [19] Views alternated between pastoral landscapes of infinite meadows and placid lakes, and intimate woodlands filled with dense vegetation, rocky outcrops, rustic architecture, meandering streams, and dramatic waterfalls. Nature was meant to be the compelling force that drew visitors into the Park, immersing them in these pastoral and picturesque landscape long before arriving at any formal landscapes or manmade structures. Calvert Vaux expressed this priority succinctly: "Nature first, and 2nd & 3rd. Architecture after a while." [20] This philosophy was evident in the siting of the Park's principal architectural feature, Bethesda Terrace, which Olmsted and Vaux deliberately situated over half a mile from the main southern gates.

Figure 6. Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, The Terrace (detail), depicting Stebbins’s Angel of the Waters fountain, published in January 1863, Library of Congress.

In 1858, Calvert Vaux began designing what he called “the water-terrace,” also referred to as “the Italian terrace,” initially without any sculptural decoration. By the time the Third Annual Report was published in January 1860, Vaux had proposed adding figures representing the seasons, although the central fountain remained unadorned.

Sometime between the summer of 1860 and July 1861 — without any documented invitation from the board— Emma Stebbins submitted a drawing of a fountain design. This timing coincided with her brother’s tenure as chairman of the Standing Committee. [21]

By January 1863 — still with no formal approval, and nine months before she received the official commission — Stebbins’s Angel of the Waters appeared as the frontispiece of the Sixth Annual Report (Figure 6). A month earlier, the commissioners also ordered neoclassical figures representing the four seasons (Figure 7). [22]

Contrary to existing literature, Henry did not resign from his role as a Central Park commissioner after being elected to Congress in November 1862 — a step that would have prevented the conflict of interest involving both him and his sister. Instead, his influence grew. Just a month before the election, he was appointed president of the board, a position he held for the next seven years. Although he stepped down from the Standing Committee, newly amended by-laws made the president ex officio member of all standing committees. [23] In October 1863, that dual authority enabled him to ensure the fountain commission benefitted both his sister and his wallet.

Figure 7. Emma Stebbins, Studies of the Seasons, Archives of American Art.

The board explicitly stated in 1863 that the Terrace's "sculpture of an expensive character" could not be funded by the city, suggesting instead that it be financed through "the liberality of individuals, or" — as they vaguely added — "in some other way." [24] A year later at the height of the Civil War and with a "considerably diminished" Park workforce, the board reversed its policy, making an exception for the fountain’s funding. During Henry’s presidency, Emma Stebbins received slightly over $2,000 for the Angel of the Waters figures, now paid for by the city rather than by private financing, which most likely would have been her brother. [25]

While Henry procured these commissions for his sister, another member of the Standing Committee, Charles Handy Russell, was deeply invested in awarding important Park projects to his “friend” and future brother-in-law Richard Morris Hunt. Vermont-born Hunt was the first American to study architecture at the École de Beaux-Arts in Paris during the Second Empire of Napolean III. He returned to New York in 1857 and received immediate recognition for his design of the Tenth Street Studio, the first American building created for working artists. That same year he and Calvert Vaux were two of the thirteen founding members of the American Institute of Architects.

Russell and Stebbins appeared to have tacitly agreed to divide the commissions without regard for the views of the Park’s designers, Olmsted and Vaux. Hunt would receive architectural projects, while Emma Stebbins would be awarded the commissions for sculpture, but not before some jockeying for position played out behind the scenes. Notably, neither man considered holding open design competitions that would have allowed other artists to compete for these prestigious awards.

While Stebbins was working on designs for the Terrace fountain, Hunt received the commission to alter the Arsenal. Built in 1851 as a munitions storehouse, the commissioners had only vague plans for its future use. While Hunt’s plans received high praise, the secretive consultation process deeply offended Frederick Law Olmsted, the Architect-in-chief, who felt the board had bypassed his authority by consulting an outside architect. In a polite but confrontational letter to Stebbins, Olmsted wrote, "Am I wrong to feel the least annoyed by the apparent want of confidence of your Committee in bringing 'professional talent' on the Park without letting me know the motive?"

The following day, the motive was revealed. Stebbins hastily attempted to downplay Olmsted's concerns, explaining that Hunt was simply a "friend" of Russell's whose views the committee wanted to hear from. To placate Olmsted, Stebbins claimed they intended to pass Hunt's ideas on to Calvert Vaux, the Park's official architect and further assured Olmsted that should the committee choose to hire Hunt, it would naturally go "through the proper channels.” [26}

Figure 8. An 1860 design for the never-built arboretum extension on the site of today's Harlem Meer, New York Public Library.

But “proper channels” were ignored when Russell's influence went beyond architecture to the landscape itself. In 1860, as commissioners considered extending the Park from 106th Street to 110th Street (north of the proposed arboretum, now East Meadow and the Conservatory Garden), the board published their support for a formal design featuring geometric reflecting pools and garden beds reminiscent of Versailles. (Figure 8). [27] This design was diametrically opposed to Olmsted and Vaux's pastoral vision. The following year, the formal plan was abandoned in favor of today's naturalistic Harlem Meer. In a letter to Olmsted, Vaux identified the rejected design as the "absurd suggestions of Russell," omitting any mention of Hunt as the obvious designer. [28]

But alterations to the Arsenal or the arboretum were minor assignments when compared with designing the Park’s entrance gates, a large and prestigious commission that Hunt needed for both professional and personal reasons. In the summer of 1860, the thirty-three year old architect became engaged to eighteen-year-old Catherine Howland a member of New York and Newport aristocracy. Both the Howlands and Catherine’s cousin and guardian, William Aspinwall, vehemently opposed the match. Though all would agree that Hunt was indeed a gentleman, they disparaged his artistic vocation as being somewhat disreputable. His highly acclaimed Tenth Street Studio building would have reinforced their negative opinion of Hunt for having bohemian associations. Aspinwall insisted that the couple wait six months before a marriage could take place, hoping no doubt that their ardor for one another would cool. But Hunt had a formidable ally in Charles Russell, who was married to Catherine’s sister Carrie. Russell did everything in his power to ensure that Hunt would succeed financially and professionally to guarantee his place in both the hearts of the Howland family and New York society. [29]

During this crucial period, the Park's board requested Olmsted to submit designs for four ornamented southern gateways. By November, "general proposals for iron gateways and stone walls" were submitted to the Standing Committee. [30] These designs, created by Calvert Vaux, were notably understated and described by art critic William J. Hoppin as "nothing more than a single row of trees about the entrances, protected by an iron railing; and perhaps, a gate keeper's lodge on one side.” [31]

Hunt began work on gate designs in February 1861, he noted in a diary, even before the nomenclature report was completed. [32] Russell and Stebbins both knew that their demand for gate decoration aligned with their deeper agenda to create an opportunity for patronage while appearing to serve public interests. Once the board unofficially approved of Emma Stebbins for the Terrace fountain and the four seasons figures by January 1863, the stage was set for them to invite Hunt to design the four southern gateways.

Surprisingly, Hunt advocated for a competition, most likely to avoid any trace of favoritism because, by then, Russell was his brother-in-law. The board followed through in June with an offer of $500 to the winning design. [33] The ten anonymous submissions to the competition were rejected by the board. According to Hoppin the plans did not offer “a sufficient degree of originality and fitness to the surrounding features of the landscape.” [34] In essence, the designs were neither sufficiently urban nor were they adequately monumental — like Hunt’s. Three months later, the commissioners awarded the four southern gateways exclusively to Hunt. An angry Calvert Vaux saw through the charade, commenting that Hunt had slyly avoided any “nepotism insinuation” by insisting that his work was judged “on art grounds solely.” [35]

Hunt's designs reflected the mid-century Parisian Beaux-Arts style, characterized by symmetry, classical elements, and elaborate ornamentation. His entrances emphasized imperial architectural features —triumphal arches, towering columns and piers, and Greco-Roman-inspired sculptures — all tailored to complement the future cityscape. The gates aligned with the grid and faced the streets. They obscured visitors' views into the Park. Hunt’s design of the Fifth Avenue entrance even called for the removal of trees intentionally planted by Olmsted and Vaux to screen out the burgeoning city. In a letter to the commissioners, Hunt advocate William Hoppin dismissed the Park's designers and their supporters as "dreamers," mocking their vision of preserving a "sylvan retreat fit for shepherds and their flocks" as "absurd." [36]

Figure 9. Richard Morris Hunt, Gate of Peace at Fifth Avenue and 60th Street, Library of Congress.

Hunt’s monumental vision is exemplified by the Gate of Peace at Fifth Avenue and Sixtieth Street (Figure 9), today’s Grand Army Plaza. For the naturally steep topography, Hunt designed an elaborate two-tiered terrace, with an upper tier at street level and a lower tier reached via a grand double staircase that descended to the edge of the Pond. A massive fifty-foot column was topped with two figures¾a Native hunter and a Dutch navigator¾who are on the seal of the City of New York. The column rises in the center of the broad semi-circular terrace and at its base, explorer Henry Hudson is memorialized and flanked by personifications in boats of the East and Hudson Rivers. [37] Each step of the double staircase was edged by a pair of spouting jets and terminated at a plaza that featured a circular basin and a central jet. Partially hidden between the stairs Hunt created a dark, water filled grotto from which emerged the Greek sea god Neptune in a chariot pulled by four prancing horses.

At this important Park entrance, Hunt seems to have been subtly “borrowing” or “improving” on both Vaux’s Terrace and Stebbins’s fountain. His iconographic references celebrated New York City’s waters, echoing Stebbins fountain dedication to the healing powers of New York’s Croton water system. Similarly, Hunt’s vision echoed the basic elements of Vaux’s Bethesda Terrace: a formal bi-level terrace, a double staircase, a darkened arcade, and a central circular basin and fountain leading to a naturalistic waterbody.

Hunt's entrances faced widespread criticism from New Yorkers. Critics denounced the gates as "ugly and unsuitable," "feeble and worthless," and "clumsy." Even Hunt’s biographer, Paul Baker, later described them as "among the most graceless conceptions of his career." [38] The European classical style clashed with America’s prevailing taste for Gothic Revival architecture, exemplified by Vaux’s Central Park unobtrusive Dairy. Architect Russell Sturgis observed that Hunt’s classical references were too highbrow for American taste, echoing similar observations by Meigs and Crawford a decade earlier. Art critic Clarence Cook succinctly summarized the issue: "The designs are not American, and the Park is." [39]

By 1863, Olmsted and Vaux had grown increasingly frustrated with the board for undermining their artistic authority. Their resentment was particularly directed at Andrew Haswell Green, the tight-fisted Comptroller, for withholding funds they deemed essential for the Park’s construction. As for the gates, Vaux wrote to Olmsted, “the fault of secrecy and official slight rested with the Commissioners and not with Hunt,” with whom the partners maintained a cordial and professional relationship. [40] The designers resigned their positions in May 1863. However, while avoiding Green, they continued to work behind the scenes to ensure their vision for the Park prevailed and Hunt’s grandiose gates defeated.

After stalling for two years amid continuous internal controversy and public censure, Comptroller Green put Hunt’s gates on hold indefinitely at a board meeting on May 11, 1865. Russell was the only commissioner who voted against the otherwise unanimous decision. [41]

In their Eighth Annual Report the commissioners issued one of their rare aesthetic decisions. The author—likely Green—mandated that Nature was the only appropriate subject for Park designs, “rejecting all symbolism of classical or pagan mythology as relics of a past civilization.” [42] Green finally heeded Vaux’s objections and must have realized that he and Olmsted were far more important to the overall outcome of the Park than Hunt’s unpopular and inappropriate gates. When Vaux heard the good news from the Comptroller about the deferment, he envisioned the tense confrontation between him and Russell and gleefully gossiped to Olmsted, “I expect there have been some unpleasant scenes.” [43] By July, the partners were reinstated as the Park’s landscape architects.

Still, Hunt was victorious. At the same meeting in which his gates were rebuked, he was given the Green light to redesign the Arsenal as the new home for the Museum of History, Antiquities, and Art of the New-York Historical Society. In keeping with his preference for continental styles, he transformed the utilitarian brick structure into a French style chateau (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Richard Morris Hunt, Museum of History, Antiquities, and Art, New-York Historical Society, The Arsenal, Central Park, New York, New York. Exterior, Library of Congress.

Hunt’s connection to the Arsenal went back to 1860 when, as we saw, the board commissioned him to do minor alternations to the Arsenal, which Olmsted considered “the best they had seen.” [44] That same year, the New-York Historical Society, located on Eleventh Street and Second Avenue, began eyeing the building for its new Museum of Antiquities, Science, and Gallery of Art. After back-and-forth negotiations, the New York Assembly passed a bill in March 1862, authorizing the Central Park Board of Commissioners to set aside the Arsenal and surrounding land for the Society. Without any apparent design competition, the Society announced in 1865 that they had chosen Richard Morris Hunt as their architect. [45]

When the Arsenal project was terminated due to conflicts between the two boards, Hunt billed the Central Park commissioners $386 for his preliminary work on the building. The commissioners then formed a special committee—excluding Charles Russell—to determine compensation for the Arsenal’s renovations and his proposed gateways. They ultimately set the amount at up to $10,000—five times what Emma Stebbins received for the Bethesda Fountain—while also disregarding any compensation for her preliminary models of the Four Seasons. [46]

Hunt never did the arboretum design, the gates, or the Historical Society’s Arsenal reconstruction, nor did he secure the commission for the Society’s second choice, the site of today’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ironically, Hunt’s renowned Beaux-Arts façade (Figure 11), designed in 1895, is one of the great landmarks of New York City and overshadows one of the museum’s former façades by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould.

Figure 11. Richard Morris Hunt, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Library of Congress.

In Central Park, Hunt is represented only by the pedestals for the Seventh Regiment Memorial and The Pilgrim, both of which support the main figure designed by sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward. Yet, despite being a bit player in the Park’s history, Hunt is the only designer to be memorialized by a structure in the Park (Figure 12). Designed by Daniel Chester French and Bruce Price and commissioned by eleven of the city's art organizations, the elaborate memorial is sited on the Fifth Avenue perimeter across from the Frick Collection, the former site of his classical gem, the Lenox Library.

Figure 12. Daniel Chester French, Richard Morris Hunt Memorial, Central Park. Photograph courtesy of author.

Even though Hunt’s carried on with a prolonged six-year campaign to install his gates, they were never realized. Yet his vision for grand, monumental entrances ultimately prevailed by the turn of the century. The Beaux-Arts monuments at Grand Army Plaza and Columbus Circle, created during the Gilded Age, align more closely with Hunt’s urban vision than the pastoral one of Olmsted and Vaux.

Figure 13. In 1999, the names of the twenty original gates were inscribed into the walls of the Park. Photograph courtesy of Author.

In the 1950s, a spark of revival for the nomenclature of the gates emerged when Commissioner Robert Moses partnered with a donor to carve the names of a select few gates into the walls of the Park. [47] Fast forward to 1999: another Henry, park commissioner Henry Stern—a man with an obsessive passion for names and naming—took up where Moses had left off. He commissioned the Central Park Conservancy to inscribe the remaining names onto the adjacent walls at the original gates (Figure 13). "Naming makes everything more important," Stern proclaimed. "If a place has a name, you know what it is, and you can refer to it." [48]

Yet, despite these inscriptions, New Yorkers still refer to the breaks in the wall as “entrances” and identify them by the location of the adjacent streets. As for the projected sculptures meant to accompany each named gate, only Samuel F.B. Morse—presenting his telegraph—is fittingly placed inside Inventors’ Gate at Fifth Avenue and 72nd Street, standing true to the original vision of the Standing Committee.

The political struggles behind the Park's artworks, particularly the gates, have largely faded from public memory, yet they remain deeply embedded in the Park's legacy. The creation of Central Park was a collaborative effort, uniting scholars, artists, artisans, and merchants, who now as then, remain honored at the four southern gateways. Every one of the Park's unadorned and unbarricaded entrances reflects the essence of democratic values and civic optimism best expressed by a frustrated Calvert Vaux, who, amidst the political turmoil, exclaimed, "How fine it would be to have no gates [and] to keep open House and trust all always.” [49]

Sara Cedar Miller is Historian Emerita, Central Park Conservancy since 2024. She was the Photographer and Historian for the Conservancy from 1984 to 2024. Miller is the author of Central Park, An American Masterpiece (2003), Seeing Central Park (2008, 2019) and Before Central Park (2022).

[1] F. L. Olmsted, Forty Years of Landscape Architecture: Central Park, eds. Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and Theodora Kimball, (Cambridge MA, MIT Press,1973), 394-397. Frederick Law Olmsted, eds. Charles E. Beveridge and David Schuyler, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Volume III, Creating Central Park, 1857-1861,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 338-341. “The Report on Nomenclature of the Gates of the Park,” Fifth Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, (New York, W.C. Bryant & Co.,1862), Appendix, 125. My deepest gratitude to Ann de Forest, Frank Kowsky, Elizabeth Milroy, Karli Wurzelbacher, and Jack Freiberg for their insightful edits and generous support, and Rebecca Pou for her help with the illustrations.

[2] The third commissioner on the committee changed frequently between John Butterworth, August Belmont and Andrew Haswell Green, who as Comptroller and Treasurer, exerted the most power on the board after Stebbins became president.

[3] “Report on Nomenclature,” 126.

[4] Richard M. Hunt, Designs for the Gateways to the Southern Entrances of the Central Park, (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1866), 14. See also, Elizabeth Milroy, “The Public Career of Emma Stebbins: Work in Bronze,” Archives of American Journal, Vol. 34, Number 1, 1994, 12, note 2.

[5] “Report on Nomenclature,” 127.

[6] “Report on Nomenclature,” 127, 128.

[7] Daniel R. Rogers, The Work Ethic in Industrial America 1850-1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978):125; Melissa Debakis, Visualizing Labor in American Sculpture: Monuments, Manliness, and the Work Ethic 1880-1935. (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 13-16.

[8] “Report on Nomenclature,” 128.

[9] “Report on Nomenclature,” 128-135.

[10] Meigs to Crawford, Letterbook, Aug. 18, 1853, Archives of the Capitol; Crawford to Meigs, Letterbook, Oct. 13, 1853, Archives of the Capitol; Charles E. Fairman, Art and Artists of the Capitol of the United States of America, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1927), 143; Robert Gale, Thomas Crawford: American Sculptor (Pittsburg, PA: University of Pittsburg Press, 1864),109; Michele Cohen, “New Perspective, New Discoveries: A Close-up Look at Crawford's Progress of Civilization,” Sept. 28, 2016. https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/blog/new-perspective-new-discoveries-close-look-crawfords-progress.

[11] Crawford to Meigs, Letterbook, Oct. 31, 1853, in Gale, Thomas Crawford, American Sculptor, 109-111.

[12] “Crawford and His Last Work,” The Crayon, Vol. 4, No. 5 (May 1857), pp. 154-158.

[13] See, Montgomery C. Meigs, Journal, Chapter 2, July 12, 86, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CDOC-106sdoc20/pdf/GPO-CDOC-106sdoc20-7.pdf; New York Times, Dec. 10, 1863, 5.

[14] From 1848 until they were forced to relocate in 1859, the Sisters of Charity of Mount St. Vincent had established a Motherhouse and a private Roman Catholic girls’ school in the prepark on the site of today’s composting operation.

[15] Fifth Annual Report, 24, 49-51, 55; First Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Department of Public Parks for the Year Ending May 1871, (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co., 1871). On January 1, 1881, the building caught on fire and Crawford’s Capitol figures were destroyed. See, New York Times, Jan. 3, 1881, 8. For the purpose of this article, we use “Miner” and “Sailor” as referenced by Henry Stebbins.

[16] “Report on Nomenclature,” 135; Milroy, “Work in Bronze,” 12 (note 2). The titles of the sculptures follow their listing in the catalogue by Karli Wurzelbacher for the 2025/2026 exhibition “Emma Stebbins: Carving Out History” at the Heckscher Museum of Art. I am grateful to the Heckscher Museum for permission to use their images in this article.

[17] “Elizabeth Milroy, “The Public Career of Emma Stebbins: Work in Marble,” Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1993, 6, note 22, 12.

[18] “Recent Works of American Artists,” New York Times, Aug. 31,1861, in Milroy, “Works in Marble,” 6-7.

[19] Letter from Olmsted to the Board, Jan. 22, 1861, in Forty Years, 310.

[20] Letter from Calvert Vaux to Clarence Cook, June 6, 1865, in Francis R. Kowsky, Country, Park, & City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 120.

[21] Third Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park 1860 (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co, 1860), opp. page 44. The date that Stebbins submitted drawing for the fountain to the board is imprecise. Stebbins’s sister, Mary Garland, assigns the submission to the summer 1860, soon after Henry became a member of the Standing Committee (see, “Letter from Mary Garland to Frank Weitenkampf, April 10,1888, enclosing her biographical sketch of her sister, the artist Emma,” New York Public Library, 6). According to Elizabeth Milroy (in “Works in Bronze,” 7) the possible end date for the submission of a drawing was July 1861. That date is based on a July 21 letter from Charlotte Cushman, who said in a letter only that the drawing had been submitted prior to Cushman and Stebbins sailing to Europe. The program for the unveiling of the fountain (in the Emma Stebbins scrapbook now in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art) noted that Stebbins modeled the fountain figures from 1864 to 1867, but that does not preclude drawings being created prior to that time period.

[22] Sixth Annual Report of the Commissioners of the Central Park, “Description of the Terrace,” (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co., 1863), 63. Minutes of the Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park For the Year Ending April 30, 1863 (New York, W.C. Bryant & Co., 1863), 49.

[23] Henry Stebbins served in Congress from March 4, 1863, until he resigned on October 24, 1864. See, Minutes of Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park For the Year Ending April 30, 1863, 25; Minutes of Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park for the Year Ending April 30, 1862, (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co.,1862), By-Laws, 5.

[24] Sixth Annual Report, “Description of the Terrace,” 63.

[25] Eighth Annual Report for the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park for the Year Ending December 31, 1864, (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co., 1865), 6-7.

[26} See, Beveridge, Creating Central Park,” note 13, 271-272.

[27] Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park (New York; W.C. Bryant,1861), map insert.

[28] Kowsky, Country, Park, & City, 166.

[29] Paul R. Baker, The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 124-125.

[30] Minutes of the Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park for the Year Ending April 30, 1861, (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co., 1861), 137.

[31] “Report of the Nomenclature,”125; Hunt, Designs for the Gateways to the Southern Entrances of the Central Park, 31.

[32] My deepest thanks to Hunt Collection librarian Mari Nakahara at the Library of Congress and Gail Wiese of the Vermont Historical Society for help with Hunt’s diary.

[33] “Office of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park,” The New York Herald, June 13, 1863, 7.

[34] Hunt, Designs for the Gateways to the Southern Entrances of the Central Park, 34. See also, Cynthia S. Brenwall, The Central Park, Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure, (New York: Abrams, 2019), 82-83.

[35] Hunt, Designs for the Gateways to the Southern Entrances of the Central Park, 15-16, Baker, The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt. 147-154. Francis R. Kowsky, “The Central Park Gateways,” ed. Susan R. Stein, The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt, (Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1986), 79-89.

[37] Kowsky, “The Central Park Gateways,” 80-81; Morrison H. Heckscher, Creating Central Park, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008), 62-64.

[38] Baker, The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt, 156.

[39] Baker, The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt,149; Kowsky, “The Central Park Gateways,” 84.

[40] Kowsky, Country, Park & City, 164.

[41] Minutes of the Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park for the Year Ending, April 30, 1866, (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co.,1866), 14.

[42] Eighth Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co., 1865), 26-7, See also, Sara Cedar Miller, Central Park, An American Masterpiece, (New York: Abrams), 2003, 56-57.

[43] Kowsky, “The Central Park Gateways,” 85, (note 26) 89.

[44] Beveridge, Creating Central Park, 272.

[45] “New-York Historical Society original buildings planning & construction records, 1848-1946,” New-York Historical archives.

[46] Minutes of the Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park for the Year Ending April 30, 1867 (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co.,1867), 99; Minutes of the Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park. for the Year Ending April 30, 1869 (New York: W.C. Bryant & Co., 1869), 55-56; Baker, The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt, 154, (note 14) 492.

[47] Meyer Berger, “Central Park Gates, Century Without Labels, Get First One,” New York Times, Mar. 19, 1954, 25.

[48] Douglas Martin, “Central Park Entrances in a Return to the Past,” New York Times, Dec.3, 1999, B17.

[49] Calvert Vaux to Clarence Cook, Jun. 6, 1865, quoted in Elizabeth Blackmar and Roy Rosenzweig, The Park and the People, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press,1992), 198, note 48, 566.