Free from the Stain: New York’s Free Produce Stores

By Charline Jao

Today, Cortlandt Street and Broadway is a busy intersection of Manhattan’s Financial District, crowded with the foot traffic of people moving to and between Wall Street, the Fulton Street subway stop, the Oculus World Trade Center, and other destinations. Though a fairly characteristic cross-street, there is a curious history to the small stores — currently a Dunkin’ Donuts, some souvenir shops, and a couple restaurants —that sit opposite the enormous One Liberty Plaza, one of many skyscrapers that tower over the area. Nearly two hundred years ago, in 1828, 1 Cortlandt Street was the site of a grocery store run by the abolitionist David Ruggles.

Ruggles, perhaps most famous for his work as a member of New York City’s Committee of Vigilance and as the man who housed Frederick Douglass after Douglass’ arrival in New York City, spent several years as a grocer while working simultaneously as a distributor and contributor to the Black press. However, the grocery store was not simply a means for Ruggles to make a living. As a prominent member of the free produce movement, Ruggles’ store offered an alternative to businesses that depended on and profited from the work of enslaved people. In highlighting the organizing activity in Ruggles’ store, and other New York City free produce stores in the nineteenth century, we can better understand how abolitionists and a vibrant free-Black community came together for a mass boycott in a neighborhood that what would become an economic hub of the United States. According to 2021 reports from the NYU Furman Center, today’s Financial District is a predominately white neighborhood with a poverty rate less than half of the citywide average. While popular images of Lower Manhattan often center Wall Street, the New York Stock Exchange, and other institutions that represent a long history of capitalism, studies into movements like free produce show that there is always a history of resistance— of both minor and groundbreaking protests — that fought against these imposing structures.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century, many abolitionists joined the mass boycott of items produced from enslaved labor known as the free produce or free labor movement. Originating in British abolitionist boycotts of sugar, free produce found a particularly strong following among Quakers and the Society of Friends. [1] Dedicated societies and groups like the American Free Produce Association and the Free Produce Association of Friends planned initiatives to combat slavery economically, while also emphasizing one’s individual moral duty to abstain from the products of slave labor.

This imperative was taken with strong conviction. At one annual meeting of the Union Free Produce Society in New York, a resolution was presented to argue that participation in the economy of slavery was little different from slave holding. The report read, “Resolved, That the same principle which required the Society of Friends to disown their members for the hiring of slaves, would, with equal force, require them to abstain from the produce of the slaves' labor.”[2] The language of haunting and cannibalism appear in many free produce texts, emphasizing the violence of complicity. For instance, in 1834, an abolitionist couple handed out papers with the couplet “Eat this candy without fear,/No blood of slaves is mingled here” to their wedding guests – a promise that feels both metaphorical and literal.[3] Even as free produce often adopted the language of economy, as Harriet Beecher Stowe did when she claimed that “Slave labor is as wasteful and unprofitable compared with free labor, as it is immoral,” free produce was most persuasive when it emphasized Northern complicity, since the consumption of goods, it was argued, implicitly supported the violence of their production. [4]

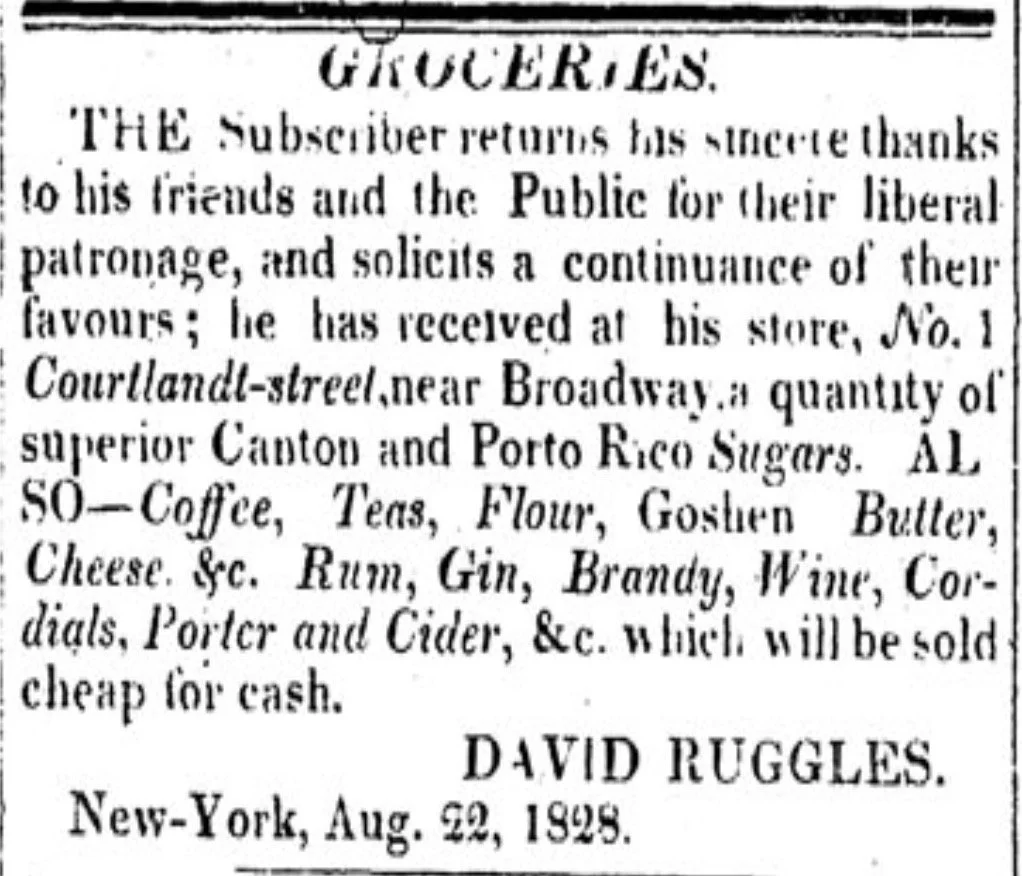

“Groceries,” Freedom’s Journal, August 22, 1828. [8]

American proponents of free produce saw clearly the connection between commercial consumption and the institution of slavery, seeking to overthrow what Frances Harper called slavery’s “commercial throne.” [5] Not only did they refuse to buy items that came from southern plantations, they also sought to create new networks of trade, labor, and production. Ruggles, for instance, did not only secure “free” butter from Goshen, New York for his customers, he also employed formerly enslaved men like Samuel Ringgold Ward and Isaiah Harper Ward. [6] Advocates of free produce set out on expeditions to find alternatives to sugar, reached out to farmers and merchants, did speaking tours in England, and opened stores where they could proudly state — as Elizabeth Kent in Pennsylvania did — that they had “EVERYTHING FOR SALE EXCEPTS PRINCIPLES!!” [7]

At his store, Ruggles initially offered dry goods, groceries, and a range of alcoholic products. The inventory would change later based on both what he was able to acquire and the moral principles he attached to certain items; and when he converted to the temperance movement, as several abolitionists did, he no longer sold liquor at his store. At Ruggles’ grocery shop, which also served as a circulating library and reading room (described by the David Ruggles Center as the nation’s “first black-owned bookstore”), we observe the multiple fronts of Ruggles’ advocacy—of the practical and ideological work of anti-slavery. [9]

A couple months after Ruggles moved his business to 36 Cortlandt Street, the store was broken into, robbed, and set on fire by a white mob—a large blow to Ruggles’ livelihood. Reopening another store at 3 Cortlandt Street, where he remained until 1832, and then moving again to 15 Cortlandt Street, Ruggles eventually closed his grocery in 1833. [10] After working as an agent for the weekly newspaper the Emancipator, he then went on to open an anti-slavery bookstore and circulating library at 67 Lispenard Street. Ruggles biographer Graham Russell Gao Hodges notes that his working relationship with female abolitionists like Maria Stewart and figures like the Tappan brothers made his store “a designated place of sale for black writings.” [11] When examining this period of Ruggles’ life, especially impressive for his young age, we see his growing commitment to the Black press in his work as an abolitionist. While working as a free produce grocer, he became a part of these networks by advertising in Black periodicals, distributing for them, and eventually working for them.

"The Autographs for Freedom," Frederick Douglass' Paper, May 5, 1854 (showing Autographs for Freedom for sale at a free labor store) [13]

Ruggles was far from the only New Yorker who took up this endeavor. In the first half of the nineteenth century, New York City was home to a number of free produce stores. By tracking advertisements in abolitionist newspapers like Freedom’s Journal, the National Era, the Liberator, and the National Anti-Slavery Standard, we see that lower Manhattan in particular housed many of these stores – a clear reflection of the extensive Black population in the fifth and sixth ward. At various points in the 1830s and early 1840s, Perkins & Towne on 141 Bowery kept good-quality and cheap “free labor Molasses, Sugar, Rice and Coffee,” L.H. Nelson sold groceries and tea on 53 Anthony Street, William Grey &Co. sold groceries on 33 Sullivan Street, and Charles Collins sold his goods at 3 Cherry Street. [12] In 1833, merchant Joseph H. Beale opened a wholesale store at 71 Fulton Street dedicated to free produce, making use of his connections abroad to secure rice and other goods. Beale later moved to 376 Pearl Street, where he continued selling everything from sugar to umbrellas, to candlewicks and table diapers—all without connections to enslaved labor. [14]

Despite many passionate societies and practitioners, historians such as Carol Faulkner note that the free produce movement is treated as a small aspect of anti-slavery organization, discounting its significance and ability to “confront the profound connection between northern consumers and slaves.” [15] Still, free produce – whether for costliness, lack of convenient, or unreliable quality—never gained the widespread popularity it desired. Records from newspaper ads and association reports show that these stores struggled to remain open and were not easy to maintain. In 1848, the National Era announced that Hoag & Wood (Lindley M. Hoag and George Wood) opened a groceries and cotton goods store at 377 Pearl Street with the assurance that “nothing which is the produce of Slave Labor shall be admitted into their store.” [16] Their stock was purchased later that year by Robert Lindley Murray who continued the business at the same location. The Murray advertisement for the National Era is much more conscious of what it calls “the disadvantages which a store of this kind is under, when compared with those which make no distinction between the products of Slave and of Free Labor.” Some dry goods, it notes, “must for the present be [priced] somewhat higher.” [17]

Eventually, Murray’s store shuttered. In the 1852 yearly report of the New York Board of Managers of the Free Produce Association of Friends, secretary Isaac H. Allen describes the impending closure of Murray’s store: as “the business of the past year has not only yielded no remuneration for his own time, but had not even been sufficient to meet the expenses of the store.” The board directs readers to Ezra Towne, who kept a free produce store on 86 Pearl Street, with a “large assortment of Dry Good and Groceries, free from the stain of Slavery,” to “friends of our cause.” [1st 8] Many abolitionists also grew increasingly disillusioned with free produce, as the efforts to find alternatives failed, support declined, and more pressing matters seemed to emerge. Some former supporters denounced it altogether – Henry Lloyd Garrison, once a supporter of free produce, later rejected it for its impracticability and suggested that it would not change slaveholders who were led “not [by] the love or gain, but the possession of absolute power, unlimited sovereignty.” [19] The following year, the Association’s report called it “painful and humiliating to be obliged to chronicle among ourselves, an apparent decline of interest in this deeply interesting and important cause.” Towne’s recent relocation to 207 Fulton Street is mentioned, where the 1853 report states it was “very poorly remunerative to him.” [20]

The study of free produce is the study of a movement that, despite its passionate followers, failed to create a strong and lasting impact on the economy of slavery. Many expeditions and initiatives failed to find suitable replacements for Southern products. Free labor store owners struggled with the same problems many models of ethical consumption face: the financial cost of running an ethical business within a capitalist marketplace. They just could not win against their cheaper, less ethical competitors. Moreover, the sentimental language which emphasized moral purity of the body could often fall into a questionable distaste for the Black bodies the movement claimed to advocate for, or, through a valorization of consumerism that emphasized individual morality over political change, this rhetoric could erase the enslaved altogether. By emphasizing the complicity of the consumer, however, free produce nevertheless argued that there was no neutral stance on slavery – that it was present on Northern shelves and in the home. And, as stores like Ruggles’ demonstrates, free produce stores were also gathering places and sites for the circulation of print. In other words, ethical consumption was far from the only cause on their minds.

By tracking the opening and closing of free produce stores, one sees that this abstinence was not passive activity for many abolitionists. Rather, it was tied to calls for immediate abolition and multiple forms of solidarity with the enslaved. In New York City, this work contributed to a greater tradition of boycott and business in the free-Black and abolitionist communities of Lower Manhattan. Their movement also testifies to Northern practices of anti-slavery that saw domestic life as a profoundly political domain.

Charline Jao is a PhD candidate studying nineteenth-century American literature at Cornell University’s Literatures in English Department. Her dissertation, “Early Lost,” looks at the temporality of child death and separation in texts by nineteenth-century American women writers. She is the creator of two digital humanities projects, Periodical Poets and No Stain of Tears and Blood.

[1] At the same time, Carol Faulkner notes this perception has overshadowed prominent non-Quaker supporters like Henry Highland Garnet, Frances Harper, David Lee Child, and Gerrit Smith. See: Carol Faulkner, “The Root of the Evil: Free Produce and Radical Antislavery, 1820-1860,” Journal of the Early Republic, 27:3 (Fall, 2007), 337-405 (p. 379).

[2] John Hambleton, “Union Free Produce Society,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, September 29, 1842.

[3] B.W., “Mr. GARRISON—I have a little incident,” The Liberator, March 15, 1834.

[4] Harriet Beecher Stowe, “Letter from Mrs. Stowe,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, January 20, 1854.

[5] Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, “On Free Produce,” A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader ed. by Frances Smith Foster (New York: The Feminist Press at The City University of New York, 1990), 44-5.

[6] Graham Russell Gao Hodges, David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 46.

[7] “Free Labor Store,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, February 24, 1842.

[8] “Groceries,” Freedom’s Journal, August 22, 1828.

[9] “David Ruggles,” David Ruggles Center for History and Education <https://davidrugglescenter.org/david-ruggles/> [Accessed 31 October 2023].

[10] Hodges, 45-6.

[11] Hodges, 60-2.

[12] “Free Labor sugar,” The Colored American, June 15, 1839; “L.H. Nelson,” Weekly Advocate, January 14, 1837; “Free-Labor Goods,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, June 30, 1842.

[13] “Wholesale Free Produce Store,” Genius of Universal Emancipation, April 1, 1833.

[14] “Free Labor Store,” The Liberator, October 4, 1834.

[15] Faulkner, 379.

[16] “Free Produce Store,” The National Era, February 24, 1848.

[17] “Free Labor Produce,” The National Era, October 5, 1848.

[18] Isaac H. Allen, Report of the Board of Managers of the Free Produce Association of Friends, of New-York Yearly Meeting (New York: Collins, Bowne & Co, 1852), 3-4.

[19] Julie L. Holcomb, Moral Commerce: Quakers and the Transatlantic Boycott of the Slave Labor Economy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 166-7.

[20] Allen, Report of the Board of Managers of the Free Produce Association of Friends, of New-York Yearly Meeting (New York: Collins, Bowne & Co, 1853), 5.