An Excerpt From Making Long Island: A History of Growth and the American Dream

By Lawrence R. Samuel

Beginning in the Roaring Twenties, Wall Street money looked eastward to generate wealth from a burgeoning land boom. After the Great Depression and World War II, Long Island — Nassau and Suffolk Counties — emerged as the site of the quintessential postwar American suburb, Levittown. Levittown and its spinoff suburban communities served as a primary symbol of the American dream through affordable home ownership for the predominantly White middle class, propelling the national mythology steeped in success, financial security, upward mobility, and consumerism. Starting in the 1960s, however, the dream began to dissolve, as the postwar economic engine ran out of steam and Long Island became as much urban as suburban. Over the course of these decades, the island evolved over the decades and largely detached itself from New York City to become a self-sustaining entity with its own challenges, exclusions and triumphs.

Undersized Manhattan Island is needed for other purposes than housing the masses of the New York City of tomorrow, which will be Long Island.

—D.E. McAvoy, 1927

The Garden Spot of the World

In 1923, P.H. Woodward, general passenger agent of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR), waxed eloquently about Long Island in a piece for the New-York Tribune. “The future of Long Island is beyond the comprehension of any of us,” his guest article began. Woodward thought it obvious that there would be a tremendous growth in population, as the island appeared to be “the natural outlet for the thousands who must leave the crowded city annually.” Montauk Point was a natural spot for industrial development, he believed, and the three hundred thousand or so acres of “practically uninhabited land” in Nassau and Suffolk Counties were just waiting to be turned into prosperous towns and villages. “Nowhere can be found such wonderful places for homes, for vacations, for sports of all kinds, for health and rest, for food supplies, and for industries,” he told the many urban readers of the newspaper, concluding that “Long Island is the garden spot of the world.” [1]

As Woodward was an employee of the LIRR, it wasn’t surprising that his article (titled “Observations of Long Island Seer”) was more advertorial than editorial. But the 1920s really were a golden age for Long Island, most famously symbolized by the grand estates of the Gold Coast and immortalized in The Great Gatsby. While modern times had no doubt arrived — planes, trains and automobiles seemed to be everywhere — Long Island remained heavily rural, more a string of small towns than the vast suburban development it would become. The pressures of the modern age could be felt on the island, however, with a faster way of life and a greater emphasis on money, much of it driven by the city residing just to the west. Women, too, were different than they had been before the Great War, more independent and less likely to be content as second-class citizens. Many men had returned from the war to end all wars in a fragile state, and Prohibition made it somewhat more challenging to find a beverage that might soothe one’s nerves.

It was the continually expanding national economy, however, that had the greatest impact on the dramatic development of Long Island after World War I. Through the 1920s, Wall Street gradually picked up steam to the point where anyone with a tidy sum to invest could multiply their money. Large investors formed syndicates with real estate developers, seeing the wide-open fields and declining estates on Long Island as prime property to transform into housing for the burgeoning middle class. Young, married New York City businessmen were the primary target, as these rent-paying apartment dwellers would be most attracted to the idea of owning a home in the cleaner, more bucolic suburbs for themselves and their families. The land boom of the 1920s was steadier than the real estate rollercoaster of Florida in the Roaring Twenties and laid the foundation for the Long Island we know today.

Quite the Natural Thing

That aviation would play a significant role in Long Island’s history could already be detected in the 1920s. Model-Ts were rolling off Henry Ford’s assembly lines in great numbers as the decade began, but some of the upper crust were already giving up their motorcars for faster transportation. “Ultra-smart Long Island is right now in the process of bidding farewell to automobiles as pleasure vehicles and is ushering in the privately owned airplane as the proper medium for use in attending afternoon tea and the theater,” Quinn L. Martin announced in the New York Tribune in 1920. Airplanes of various makes and models could be seen in the backyards of some wealthy homeowners in Garden City, Long Beach, Greenport, and Port Washington and, increasingly, the skies all over the island. Flying enthusiasts, like Lawrence B. Sperry of Garden City and Albert R. Fish of East Marion, were convinced that airplanes would in the near future eclipse cars as Americans’ vehicle of preference. “We will go to church in them, to the opera, to our work, to the beach, and to the South in the winter,” Sperry stated, thinking aviation to be “quite the natural thing.” [2]

Until such a time, however, automobiles remained a relatively speedy way to move about Long Island. Roads in the early 1920s were notoriously bad, however, making any journey of significant length an adventure. Merrick Road east from Queens to Amityville was a common route for motorists, as it was roughly paved, but dirt roads likely awaited those wishing to then go north to Farmingdale or south to Babylon. Already there were speed laws in place, however, with Nassau County’s finest on motorcycles ready to give tickets out to those exceeding the limit of ten or twenty miles per hour. [3]

Fig. 1 A 1931 Automobile Map of Long Island.

Despite less-than-ideal driving conditions, urbanites were encouraged to see the bucolic wonders of Long Island via an automobile. In fact, one could take a two-hundred-mile round trip from and back to Manhattan, although plenty of twists and turns (and the occasional detour) awaited those who accepted the challenge. After crossing the Queensboro (or Fifty-Ninth Street) Bridge and winding one’s way through Queens, one would pass “magnificent estates, parks, country clubs, woods, fields, and seashore,” an Automobile Club of America tour promised, an experience that would “prove generally invigorating and refreshing.” [4] For those who had the time (and gasoline), the eastern end of Long Island offered city dwellers a glimpse at what was still “wild country.” “The landscape is often harsh and grim, with the uplands clothed by a thin, wiry grass, with here and there a clump of stunted trees,” a reporter told readers, “a picture worth going far to see.” [5]

While the summer was considered the best time for New Yorkers to escape their (pre-air-conditioned) apartments for some fresh air and spectacular views, it was the fall to which Long Island society most looked forward. Summers might very well be spent in the even cooler New England or perhaps taking the Grand Tour, but autumn was the season to see and be seen among the Long Island A-list. Those among that elite were especially anticipating the fall season of 1920, as due to the war, it had been a number of years since it was considered appropriate to exhibit such merriment. The Piping Rock Club in Matinecock (now part of Locust Valley) had arguably the most beautiful grounds of any country club in the country, one reason why its autumn horse show was an event not to be missed by anyone lucky enough to be invited. Golf or, even better, polo at the Meadow Brook Club in Jericho was another staple of the season that unofficially began with the opening of Belmont Park in Elmont. “Soon all the big estates on the island will be opened, and there will be much entertaining in the way of weekend house parties, dinners, and dances,” the New-York Tribune noted in early September that year, with the social scene shifting to Manhattan in the middle of November. [6]

Although the big estates and sprawling country clubs occupied by millionaires took up considerable land, their collective acreage was a small fraction of the entire island. More than half of the acreage in each county was either devoted to working farms or wholly undeveloped land, however, the remainder being villages and towns, private estates, golf and country clubs and cemeteries and parks. Very soon, both real estate developers and some of the more than five million residents of New York City would start thinking that these unoccupied hundreds of thousands of acres might make a good area for non-millionaires to settle down. Taking an automotive drive around the island, as many New Yorkers were doing, made it clear that this land of seemingly endless potato farms and beaches could very well be a nice place not just to visit but to live. [7]

There were other reasons why it was becoming clear that Long Island was prime for development. While it was not the most reliable form of transportation, the LIRR was gradually expanding its routes, an attractive thing for those considering commuting to and from their jobs in New York City. As well, Long Island was viewed in positive terms—a reflection of it having been the playground for the rich and famous for decades. This could not be said to be true of New Jersey, which had already become somewhat of a running joke among more sophisticated New Yorkers. “Long Island has always been peculiarly close to New York City in popular imagination,” an editor for the New-York Tribune observed, thinking “the jests which have represented New Jersey as an alien strand never touched the land of Hempstead, Ronkonkoma, Sag Harbor, and Montauk Point.” [8]

The year 1921 turned out to be a record one for home building on Long Island, as a postwar housing shortage in New York City further incentivized urbanites to look elsewhere to live. The opportunity to own one’s home rather than pay rent was yet more motivation to go beyond the city limits, even if it did mean commuting to work or moving away from friends and family. Construction firms were doing quite the business in Nassau and Suffolk, building not just homes but also stores, factories, theaters, garages and churches. In Nassau, the most buildings being put up were in Freeport, Lynbrook and Long Beach, while in Suffolk it was Huntington, Bay Shore and Patchogue. The LIRR was carrying eastward not only passengers but also hundreds of thousands of tons of materials needed for construction, such as lumber, cement, bricks and plaster. “These figures indicate how fast Long Island is growing,” said the general freight agent for the railroad, asserting that his trains were better than trucks for transporting heavy materials given the state of some of the roads on the island. [9]

The year 1922 was turning out to be even stronger in building activity on Long Island, and by the fall, it was expected to break the previous record that had been set in 1912. While not a boom, there was “a steady market with a constantly growing demand,” as the New York Times reported. Buyers of both homes and commercial real estate were expected to improve their property, the goal being to raise the value of the larger community. The typical path of suburban development was the formation of a town followed by municipal improvements and then land sales combined with the erection of houses and other buildings. It was the reselling of properties where the biggest profit-making opportunities resided, however, a process that created liquidity for further investment and development. On the South Shore, the Island Park-Long Beach area was following such a step-by-step formula orchestrated by brokerages, which were in a position to make the most money through constant turnover, while Port Washington was the prime example on the North Shore. Landscape architecture and financing were other integral components of this systematic approach to suburban development that was becoming the model for more Long Island towns, especially those near the water. [10]

While the transformation of large Long Island farms into suburban home lots had begun in the first decade of the twentieth century, the escalating real estate market of the early 1920s was understandably getting much attention among more developers. “Throughout Nassau and Suffolk counties the towns and villages are taking on a city suburban aspect, and almost to Montauk Point the region is being taken over as the outlying limits of the great city,” the Times noted. [11] W.R. Gibson, who had found considerable success developing three thousand homes in Queens, was now looking east as opportunity knocked. Gibson and his associates had just purchased five hundred acres to build “small attractive homes in the nearly Long Island suburbs for the salaried man who wants to get out of the city,” as the New-York Tribune reported. Two hundred houses would immediately be put up in Valley Stream, Lynbrook, Hewlett and Woodmere (my hometown), with the average price between $5,000 and $8,000. “Some of the houses will be more expensive but it is the middle-class home seeker that the company has in mind,” the newspaper added, with Gibson guaranteeing that every homeowner would have a lawn between his house and the street. [12]

Hit the Sunrise Trail

Not just real estate developers and brokers saw a gold mine in Long Island but also hotel and restaurant operators. The continuing popularity of automobiles was a windfall to those in the hospitality trade who fully recognized the business to be had from motorists looking for a place to eat or stay overnight. In 1922, the Hotel Men’s Association of Long Island met in Long Beach and conceived a “Boost Long Island” promotion campaign to try to attract more guests. Tourism had never been aggressively marketed on Long Island, but that was beginning to change as more of the middle class pursued recreational activities like golf and beachgoing on weekends and vacations. The theme of the campaign was “Hit the Sunrise Trail,” one of many references to the geographic trajectory of the sun that would be attached to the island that lay east of New York City. “Long Beach should be another Atlantic City,” declared one of the boosters, and the possibilities for hoteliers were limitless, even if alcohol could not be (legally) served. [13]

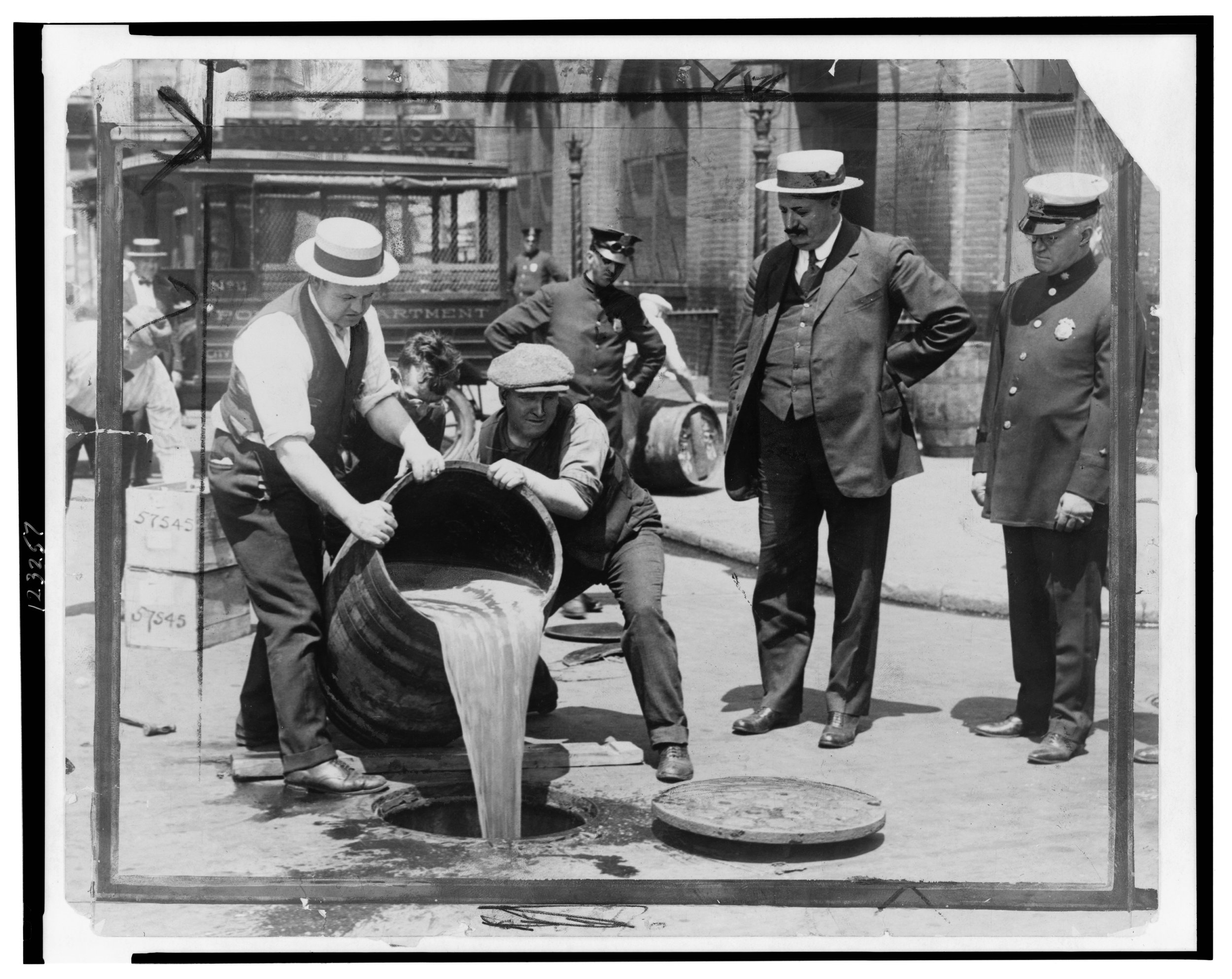

Fig. 2 New York City Police and Treasury Agents Following a Raid.

Some of those hitting the sunrise trail were themselves finding the hospitality business to be limitless despite Prohibition. Riverhead and Sag Harbor had become the favored drop points for rumrunners among New York–based bootleggers, who would then truck the stuff back to the city. (Enforcement agents had cracked down on similar activity in Freeport and Long Beach, making the bootleggers move their business.) Large numbers of armed thugs were arriving in otherwise empty trucks and meeting up with the operators of speedy, booze-laden boats on the shore. (The boats had been used as submarine chasers during World War I.) Many fishermen and oystermen in those towns had reportedly given up their trades, finding boat unloading or reselling inventory to be a much more lucrative occupation. There was so much Scotch whisky arriving in 1923 that a bottle could be had for just four dollars a bottle or forty-five dollars a case, a very good deal given the usually high price for decent booze during Prohibition. [14]

Lawrence R. Samuel is a Miami- and New York City-based independent scholar. He is the author of The End of the Innocence: The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair (2007), New York City 1964: A Cultural History (2014), Tudor City: Manhattan's Historic Residential Enclave (2019), and Dead on Arrival in Manhattan: Stories of Unnatural Demise from the Past Century (2021). This blog is adapted from his latest book, Making Long Island: A History of Growth and the American Dream (The History Press, 2023).

[1] P.H. Woodward, “Observations of Long Island Seer,” New-York Tribune, April 22, 1923.

[2] Quinn L. Martin, “Long Island Society Will Be ‘Up in the Air’ This Summer,” New-York Tribune, April 11, 1920.

[3] “Merrick Road Reported in Fairly Good Shape,” New-York Tribune, May 11, 1920.

[4] “You Can Drive 200 Miles on Good Long Island Roads,” New-York Tribune, July 25, 1920.

[5] “Extreme Eastern End of Long Island Is Tour’s Objective,” New-York Tribune, August 7, 1921.

[6] “Long Island Ready for Gay Autumn Season,” New-York Tribune, September 8, 1920.

[7] “How Long Island’s Million Acres Are Utilized,” New-York Tribune, January 9, 1921.

[8] “Passports for Long Island?” New-York Tribune, April 22, 1921.

[9] “16,697 Families Built Homes on Long Island Last Year,” New-York Tribune, February 19, 1922.

[10] “Active Lot Market in Near-by Suburbs,” New York Times, October 8, 1922.

[11] “Booming Long Island,” New York Times, November 12, 1922.

[12] “500 Long Island Acres Bought for Small Home Sites,” New-York Tribune, February 18, 1923.

[13] “Long Island Hotels Begin Campaign to Win More Visitors,” New-York Tribune, April 6, 1922.

[14] “Rum Smugglers Stir Many Towns,” New York Times, March 17, 1923.