Tong Kee Hang: A Chinese American Civil War Veteran Who Was Stripped of His Citizenship

By Kristin Choo

On October 16, 1908, Civil War veteran Tong Kee Hang received a terse letter. “Sir—You are requested to call at this office tomorrow at 10 o’clock a.m. Please bring your pension certificate with you. Respectfully, Hugh Govern Jr. Assistant U. S. District Attorney.”

“I got the letter last Friday and worried all that night trying to figure out what it meant,” Hang, also known as John or William Hang, told a reporter a week later. “But that I was to be deprived of my citizenship after 50 years in the United States never entered my mind.”[1] Unfortunately, that was exactly what happened. By order of Judge James E. Blanchard of the New York State Supreme Court of New York County, Hang’s 1892 naturalization was voided.[2] At the age of 67, Hang was a man without a country.

People who knew Hang were appalled. “Everybody in the First Assembly District and half the people of Staten Island know this old Chinese veteran and are unanimous in saying that the old man has got a pretty rough deal,” wrote the reporter.[3] But Assistant US Attorney Govern declared that it was “well-known to all Chinese that no person of the Mongolian race, Chinese, Japanese or Korean,” was eligible for citizenship unless born in the United States, and that Hang ought to be grateful he was not prosecuted.[4]

John A. Hang, circa 1911, “The Blue, the Gray and the Chinese American Civil War Participants of Chinese Descent.”

Far from being grateful, Hang was devastated. “It seems to me a man ought to have something to say about running the government for which he offered his life,” he told a reporter in 1911. “I’m as much an American as anybody else.”[5]

May is Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage month, an appropriate time to recognize the Chinese Americans whose lives were disrupted, constricted or uprooted by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and other racist laws and policies. Tong Kee Hang did not suffer the most egregious mistreatment meted out to Chinese immigrants during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was not beaten, lynched, or driven from his home like many others.[6] But the loss of his citizenship and right to vote was a cruel blow for a man who had served his country in wartime and who took deep pride in being American.

Hang was only a teenager when he first set foot in New York in the late 1850s. His father had paid an American ship captain to bring his son from Canton (now Guangzhou) to the United States.[7] At the time, there were few Chinese immigrants in the city. An 1855 municipal census showed only 38 Chinese residents, many of them sailors.[8] Over the next few years, Hang, too, worked as a seaman, sailing back and forth to Europe on various merchant ships.

But on July 24, 1863, with the Civil War raging, the now 22-year-old Hang enlisted in the US Navy at Brooklyn Navy Yard under the name of John Ah Heng.[9] Perhaps he heard about a law approved by Congress on July 17, 1862, offering a fast track to citizenship to noncitizens who signed up to serve in the war.[10] “I was not obliged to fight,” Hang recalled later, “but I wanted to become a citizen of this land, and its battles were my battles just as much as though I was born here instead of in China.”[11]

Serving first as a landsman and later as a cabin steward, Hang took part in the blockade of Mobile Bay under the command of Admiral William Farragut of “Damn the torpedoes; full speed ahead!” fame. Although the Navy ships on which he served occasionally came under sniper fire, he didn’t see combat himself. But he did load powder for the guns. “It was almost like watching a war through a telescope,” he recalled.[12]

On September 30, 1864, he was honorably discharged and resumed work as a merchant seaman. Around 1868, while in Savannah, Georgia, he met and married a woman named Jennie Busch. She convinced him to adopt her father’s given name, William, and settle down. He returned to New York with his family and started up two businesses, a grocery store on Staten Island and a cigar shop in Manhattan’s Chinatown.[13]

Advertisement for Wm. Ahang grocery, 1886, Webb's Consolidated Directory of the North and South Shores, Staten Island, 1886, 66.

Hang proved adept at navigating these different milieus. On Staten Island, under the name of William Ahang, he sold “fine family groceries” and “flour of all grades” to affluent professionals and businessmen in the Island’s West New Brighton neighborhood (now West Brighton).[14] In now-bustling Chinatown on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, he became a prominent figure, a part-owner of 16 Mott Street, where the powerful Chinese Charitable and Benevolent Association of New York (now the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association of New York) was headquartered.[15] When the Association was formally incorporated in 1890, William A. Hang served as a trustee.[16]

A quick search of the federal census shows Hang to be the only Chinese person living in Richmond County in 1880. Still, he seemed comfortable on Staten Island, insulated from the anti-Chinese sentiment then sweeping the country. After his wife Jennie died in 1878, leaving him a widower with two daughters, he married again in Sacred Heart Catholic Church in West New Brighton to Irish immigrant Margaret McDevitt. Margaret had worked as a servant for a family living near Hang’s grocery store.[17] (Sadly, she, too, died in 1888.) When Hang applied for citizenship in 1892, a Staten Island court approved his petition without fanfare.[18]

Thus, it came as a shock when, on August 16, 1904, Hang was hauled into federal court and charged with voting illegally. Two other prominent Chinese New Yorkers were arraigned alongside him, including tea merchant Eng Ten Lung, and Tom Lee, a powerful Chinatown restauranteur and business owner with close ties to Tammany Hall. White power brokers often dubbed Lee “the Mayor of Chinatown.” All three were naturalized and had been voting for years. But Federal prosecutors asserted that the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act had rendered their naturalizations invalid and thus their voting illegal.[19]

In the nearly 50 years since Hang arrived in the United States, anti-Chinese resentment intensified as Chinese immigration surged. A soaring demand for labor to exploit the mines, build the railroads, and otherwise develop the nation spurred the entry of thousands of Chinese laborers. By 1880, there were over 100,000 Chinese people living in the United States.[20] Labor leaders accused the new immigrants of lowering wages and stealing jobs, employing “yellow peril” tropes common in the press at the time that portrayed Chinese people as crafty, dishonest and prone to vice. California Workingman’s Party leader, Denis Kearney, himself an immigrant from Ireland, frequently ended his speeches with the slogan, “The Chinese must go!”[21]

Federal law codified these attitudes in laws like the Page Act of 1875, which empowered federal port officials to scrutinize and deny entry to “subject of China, Japan or any Oriental country” determined (on unspecified grounds) of being transported for “lewd or immoral purposes.” The law had the effect of making it harder for Chinese women to enter the United States.[22]

But it was the Chinese Exclusion Act that, in addition to shutting down the entry of Chinese laborers, explicitly banned naturalization of Chinese immigrants, stating that “hereafter no State court or court of the United States shall admit Chinese to citizenship.”[23] Even previously naturalized Chinese Americans found themselves in a precarious situation. The Nationality Act of 1790, the first federal law regulating naturalization, restricted eligibility to “free white persons.”[24] After the Civil War, the Naturalization Act of 1870 extended eligibility to include “aliens of African nativity” and “persons of African descent,” but still left out Asians.[25] Effectively, the law passed on July 17, 1862, offering fast-track citizenship to aliens who enlisted in the Civil War, did not apply to Asian veterans like Hang.

The Chinese Exclusion Act remained in effect until its repeal in 1943. It seems that in the years immediately after its passage, some local courts were either ignorant of or just ignored the law and continued to naturalize Chinese individuals. Hang was granted citizenship ten years after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, and Eng Ten Lung, the tea merchant arrested alongside Hang, obtained his citizenship in Passaic New Jersey in 1890.[26] In 1904, the government cracked down. The prosecutors who brought the case against the three Chinatown leaders bragged that they knew of “Chinamen who possessed alleged citizenship papers, and they would be arrested as soon as the Federal authorities could gather them in.”[27]

Note written on Hang’s naturalization file cancelling his certificate of citizenship, October 21, 1908, New York, U.S., State and Federal Naturalization Records, Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Still, Hang and the other men seem to have been treated lightly, convicted and released with their sentences suspended.[28] Perhaps this emboldened Hang to try again four years later when he attempted to register as a Republican. This time, a poll worker challenged him. This incident may have triggered the formal revocation of his citizenship.”[29]

Hang didn’t take it lying down. For years, he continued to agitate for the restoration of his right to vote writing letters to then-President William Taft and Secretary of State Knox, and continuing to vent to reporters.[30] The resulting publicity drew the attention of a white Manhattan lawyer named Charles Waldron Clowe, who in 1917 was researching a book on Chinatown. Clowe tried to interview Hang, but couldn’t find him. Assuming the old man might be dead, Clowe wrote to the Navy for details about Hang’s service and his date of death.[31]

This opened a whole new can of worms. The government was paying a pension of $24 a month to Hang, and if he was dead, then who was collecting the pension? An investigator was dispatched to determine if any criminal fraud was involved.[32]

Luckily for Hang, the appointed investigator, P. L. Cole of Brooklyn, was conscientious and fair. He tracked down Clowe, who admitted that he had no real information that Hang was dead. Cole talked to Chinatown residents who told him that that old veteran was a long-time fixture in the neighborhood, notable for his proudly American-style attire. He also located Hang himself living at a new address at 8 Franklin Street in Manhattan.

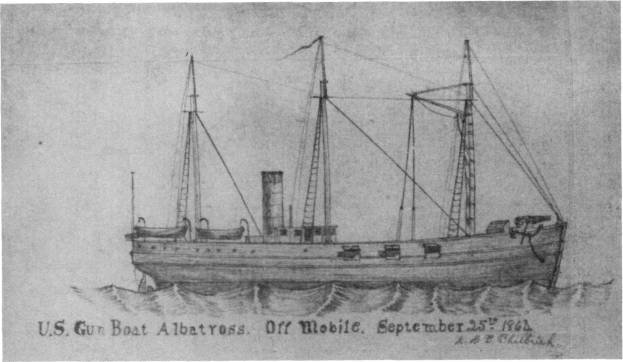

The Albatross, circa 1862, Naval History and Heritage Command.

Cole found that Hang could remember only a couple of the men he served with in the Navy. “I did not know enough about English then to remember their names,” Hang explained. But he did remember the ships: the Albatross, “a small gunboat, a screw-steamer, carried four guns on each side, one in bow, two in stern;” the Penguin, “a screw-steamer, small, with 7 or 8 guns.” He remembered specific incidents; the repair of the Albatross’s mast: jaunts to Galveston aboard the Penguin, the time an officer got shot in the foot. Convinced that Hang was who he said he was, Cole closed the case and advised the Bureau of Pensions to continue his pension.[33]

That must have been a huge relief to the 76-year-old veteran, now in failing health and unable to work. On August 14, 1919, he took up residence in the New York State Soldiers and Sailors Home in Steuben County, New York.[34] Four years later, he went from the home to Staten Island to visit the grave of his wife (wives?) and suffered a heart attack. He died on December 3, 1923 and was buried in Fountain Cemetery, where his first wife, Jennie, had been buried.[35] Hang never recovered his citizenship.

Kristin Choo is a freelance writer whose articles on legal and environmental issues have appeared in the ABA Journal, the Chicago Tribune, and Planning Magazine, as well as other publications. She resides on Staten Island and is obsessed with its history and people.

[1] “Chinese Who Fought Under Farragut Now Barred From Voting,” Evening Bulletin, October 23, 1908.

[2] “Chinaman Denationalized,” The New York Times, October 18, 1908.

[3] “Chinese Who Fought Under Farragut Now Barred From Voting,” Evening Bulletin, October 23, 1908.

[4] “Calls Chinaman Hang Lucky,” The New York Times, October 24, 1908.

[5] “This Chinaman a G. A. R. Veteran,” The Pittsburgh Press, February 25, 1911.

[6] Erika Lee, “The Chinese Must Go!” Reason, March, 2016, https://reason.com/2016/02/17/the-chinese-must-go/.

[7] “Chinese Veteran Wants to Vote,” The Hartford Republican, February 24, 1911.

[8] Fredrick M., David M. Reimers, and Robert W. Snyder, All Nations Under Heaven. Immigrants, Migrants and the Making of New York (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 46.

[9] “Weekly return of enlistments at Naval Rendezvous (“Enlistment Rendezvous”), Jan. 6, 1855-Aug. 8, 1891,397. NARA Publication Number M1953, NARA Roll 21, FHL Film Number 2381762, accessed on Ancestry.com.

[10] Sec. 21., Chap 220, Laws of the 37th Congress, Session II, page 597, approved July 17, 1862, https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/12/STATUTE-12-Pg597.pdf.

[11] “Chinese Veteran Wants to Vote,” The New York Herald, February 12, 1911.

[12] “Chinese Veteran Wants to Vote,” The Hartford Republican, February 24, 1911.

[13] Deposition of John Hang (#38665), July 28, 1917. Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Civil War and Later Navy Veterans (Navy Survivors' Certificates), 1861-1910, National Archives, https://www.fold3.com/image/6716522.

[14] Webb’s Consolidated Directory of the North and South Shores, Staten Island, 1986, 66. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

[15] “Personal,” Richmond County Advance, October 1, 1887.

[16] “Capital Notes,” Albany Morning Express, March 20, 1890.

[17] Records of Sacred Heart Catholic Church, Staten Island, New York; 1889 Federal Census Place: Staten Island, Richmond, New York; Roll: 923; Page: 77B; Enumeration District: 299.

[18] County Court Richmond County (1-9), County Court Richmond County (01-03), New York, U.S. State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794-1943. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

[19] “Prosperous Chinese Arrested for Voting,” The New York Times, August 17, 1904.

[20] Yuning Wu, “Chinese Exclusion Act.” Encyclopedia Britannica, February 9, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chinese-Exclusion-Act.

[21] “Denis Kearney and the California Anti-Chinese Campaign,” The Chinese American Experience, 1857-1892, https://immigrants.harpweek.com/chineseamericans/2keyissues/DenisKearneyCalifAnti.htm.

[22] Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2015), 67.

[23] “Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/chinese-exclusion-act.

[24] “Nationality Act of 1790,” Immigrant History, a project of the Immigration and History Society, University, University of Texas at Austin, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/1790-nationality-act/.

[25] “Naturalization Act of 1870,” Immigrant History, a project of the Immigration and History Society, University, University of Texas at Austin, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/naturalization-act-of-1870/.

[26] The Chinese Exclusion Act was set to expired in 1892 but was renewed by Congress on May 1892 for another 10 years and made permanent in 1902. “Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/chinese-exclusion-act.

[27] “Prosperous Chinese Arrested for Voting,” The New York Times, August 17, 1904.

[28] Letter from Charles Waldron Clowe to U.S. Pension Office, February 28, 1917, Hang, John ((#38665), Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Civil War and Later Navy Veterans (Navy Survivors' Certificates), 1861-1910, National Archives, https://www.fold3.com/ 67164403.

[29] “Chinaman Denationalized,” The New York Times, October 18, 1908.

[30] “Chinese Veteran Wants to Vote,” The Hartford Republican, February 24, 1911; “Chinese Veteran Wants to Vote,” The New York Herald, February 12, 1911.

[31] Letter from Charles Waldron Clowe to U.S. Pension Office, February 28, 1917, Hang, John ((#38665), Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Civil War and Later Navy Veterans (Navy Survivors’ Certificates), 1861-1910, National Archives, https://www.fold3.com/ 67164403.

[32] Hang, John ((#38665), Page 14. Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Civil War and Later Navy Veterans (Navy Survivors’ Certificates), 1861-1910, National Archives, https://www.fold3.com/ 67164467.

[33] Hang, John ((#38665), Page 61-63. Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Civil War and Later Navy Veterans (Navy Survivors’ Certificates), 1861-1910, National Archives, https://www.fold3.com/image/67165069; https://www.fold3.com/image/67165087; https://www.fold3.com/image/67165108.

[34] U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938, Page 122, National Archives: Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938, Series: M1749. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

[35] “Chinese Veteran Dies,” The Democrat and Chronicle, December 4, 1923; Find-A-Grave Memorial ID for “Tong Kee (John or William) Hang, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/200541670/tong-kee-hang.