Thinking Black, Collecting Black: Schomburg’s Desiderata and the Radical World of Black Bibliophiles

By Laura E. Helton

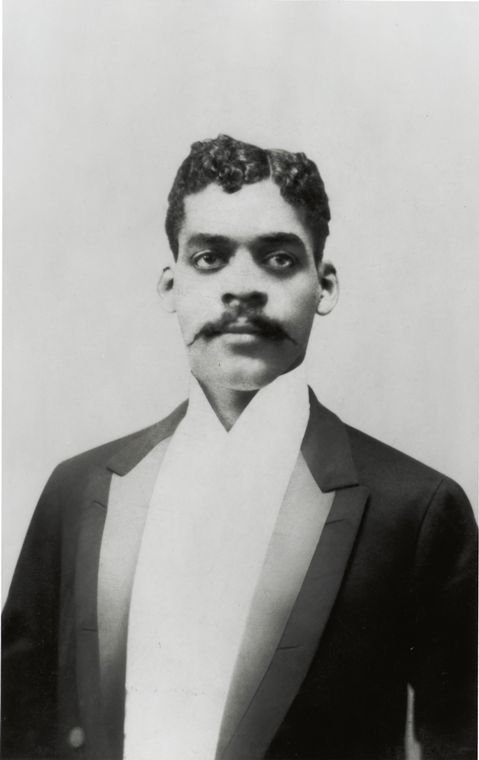

Arturo Schomburg, circa 1896, during his early years in New York City. Photographer unknown. Source: Arthur Alfonso Schomburg Photograph Collection, Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-8851-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

In 1912, Arthur Schomburg was unpacking his library—again. For many years, he had collected books, pamphlets, papers, and curios that documented Black life: verses of early poets in North America, tales of Caribbean revolutionaries, African travel narratives, histories of ancient Egypt, antislavery pamphlets, a few manuscripts, and even “coins galore.” [1] Of these objects, books especially had filled his apartment. “I have an innate love for such books which have within its covers anything good of the race,” he told a friend. [2] In loving such texts, Schomburg followed in the footsteps of earlier Black thinkers who held aloft the memory of literary and political heroes like Benjamin Banneker, Phillis Wheatley, or Toussaint Louverture. But Schomburg was not content to pen odes to these heroes. Part of an emerging cohort of Black bibliophiles at the turn of the century, he wanted their words and pictures, on paper and in his library. “To have and to Hold,” he declared. [3] He spent twelve years searching for a single engraving of Banneker’s visage. He obtained the handwritten military commands of Louverture on letterhead stamped Egalité, Liberté. He wanted every edition of Wheatley’s poems. Once he acquired them, he held fast. “No parting glances,” he responded when a dealer offered “100 plunks” for his autographed copy of “the sable poetess.” [4] Having filled three bookcases with these and other cherished things, Schomburg began to ponder his collection’s future.

At nearly forty years of age, Schomburg had made many migrations both geographic and cultural. Born in San Juan and baptized Arturo, he spent parts of his childhood in the Virgin Islands before moving in 1891 to New York City, where he adopted the name Arthur. In New York, he committed himself first to the anti-imperialist clubs of Puerto Rican and Cuban exiles and then to the Black nationalist ranks of the Loyal Sons of Africa. He made a series of smaller migrations within the city as well, from the Lower East Side to midtown’s San Juan Hill, and then to Harlem. His most recent sojourn was north from 115th Street, where he had lodged with Ramon Rothschild, an old comrade from Puerto Rico and a member of his masonic lodge. Now living in an apartment at 63 West 140th Street with his new wife, Elizabeth Green, Schomburg was the only Puerto Rican in the building of African Americans and West Indians. He was also the only resident, among porters, elevator operators, dressmakers and domestic workers, listed in the census as a “bookkeeper.” [5] That designation was a misnomer, for Schomburg worked as a clerk in the mailroom of a bank, but it was more apt than the census taker may have realized, for Schomburg was indeed a keeper of books. With each of his migrations, those books had moved, too. “I encounter much trouble when moving from one place to another this treasured lot,” he reported. The collection had grown heavy and large, and items sometimes got lost during moves. “I fear [I] have reached the limit,” he wrote in a moment of weariness. [6]

More than a century hence, we know that Schomburg had not reached his limit. His “treasured lot” kept growing until it seeded a collection at the New York Public Library that still bears his name—one of the largest in the world then and now. In 1912, however, few collections resembled his—none in public institutions—and Schomburg harbored uncertainty about its future. Publicly, he made a name for himself as “an indefatigable searcher”; privately, he worried about how to sustain his bibliographic tendencies. [7] Although he never truly considered abandoning his book-buying habits—“the Negro is ever my subject,” he declared—he began to experiment with other modes of gathering and distributing these objects of “imperishable memory.” [8] He joined forces with the Black nationalist journalist John Edward Bruce to form the Negro Society for Historical Research (NSHR), and together they dreamed of creating a “circulating library” composed of the society’s books and papers. [9] He and Bruce also contributed to the Negro Library Association’s effort to secure a building for the “proper housing of materials,” and they signed on to an idea to establish a “centre of Negro art and literature” at Saint Mark’s M. E. Church. [10] Briefly, Schomburg even contemplated a sideline as a dealer of rare books to fill shelves other than his own. None of these efforts materialized exactly as he hoped, but they led Schomburg to imagine potential readers and publics for his collection.

Figuras y Figuritas: Ensayos Biográficos by Teofílo Domínguez (1899), inscribed in 1910 from José D. Rodriguez to "Amigo A. Schumburg." Rodriguez uses the spelling of Schomburg's last name as it was often written in the 1890s, when Schomburg joined other Puerto Rican and Cuban expatriates in the revolutionary movement against Spanish imperialism. Source: Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

To publicize his holdings, Schomburg ordered a typewriter from Chicago and began preparing a list that he called both “my book index” and “my catalogue.” One version of this catalogue, typed around 1914, is the only known inventory of Schomburg’s library created during his lifetime. Titled “Library of Arthur A. Schomburg: Collection of books on the Negro race, slavery, emancipation, West Indies, South America, and Africa,” it enumerates eight hundred books, ephemera, manuscripts, and art objects, revealing what was in the “treasured lot” Schomburg struggled to move. [11] More broadly, it captures the social world of his collection: how all his migrations, both cultural and spatial, met on his bookcases. In the famous reverie of Walter Benjamin, the act of unpacking a library evokes the “bliss of the collector,” who relives the thrill of each book’s acquisition. [12] For Schomburg, such memories would often have been collective, linked to friends, comrades, and their joint expeditions. One of the books in Schomburg’s catalog, for example—Teofílo Domínguez’s Figuras y Figuritas, a portrait of Afro-Cuban separatists—was given to him by José D. Rodriguez, a cigar maker in New York, as a token of “affection and consideration.” [13] A collection of manuscript sermons, also on the list, resulted from a “pilgrimage” with his friend John W. Cromwell to recover the papers of pan-Africanist theologian Alexander Crummell. Each page was “a memento of their rescue,” Schomburg wrote. [14]

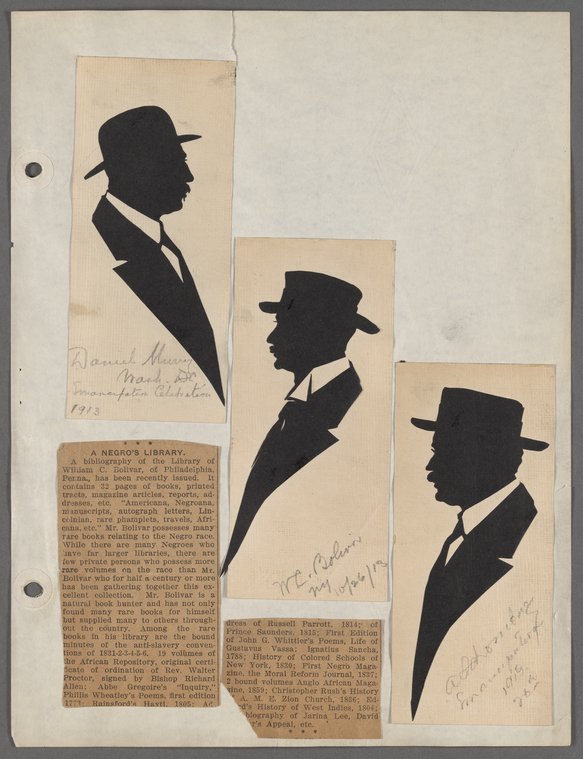

Scrapbook page with silhouettes of Daniel Murray, W. C. Bolivar, and Schomburg created in 1913 at the National Emancipation Exposition in Washington, DC. Also pasted on the page is a clipping titled "A Negro's Library" announcing the publication of a catalog of Bolivar's library (which Schomburg helped to compile) and calling Bolivar a "natural book hunter." Source: Arthur A. Schomburg Papers, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a7ad7e50-cc22-013b-fb69-0242ac110002.

As the provenance of these two items suggests, Schomburg’s collection grew out of the worlds of Black migration and organizing in the 1890s through the 1910s. In those decades, Schomburg was an organization man: secretary of Las Dos Antillas, “librarian” of Saint Benedict’s Lyceum, cofounder of the NSHR; a member of the American Negro Academy, and a Grand Master in the Prince Hall Masons. In each of these groups, Schomburg served as recordkeeper and, through these associations, he began to exhibit his materials; the first public display of objects from his library likely took place on July 4, 1912 at a community celebration held by the NSHR, where he “rejoiced at the many exhibits we had before our people.” [15] He found in these groups friends who belonged to what the Philadelphia newspaperman William Carl Bolivar called DOFOB—Damned Old Fools on Books. [16] They journeyed with one another to bookshops in search of their desiderata and corresponded about their latest finds. The artifacts that remain of their ventures—letters, inscriptions in their books, and the 1914 catalog of Schomburg’s library—document a social history of Black collecting. Together, these “damned old fools” engaged in the intellectual work of imagining what a “Collection of books on the Negro race” could and should contain.

In this circle, Schomburg also explored the concept of collectivity, engaging in a method he and Bruce each called the practice of “thinking black.” Subverting the narrow, stifling ways that the United States codified racial segregation, this method looked elsewhere—in both time and space—to harness the power of “thinking black” in diasporic and global terms. Schomburg saw the stakes of his project as at once mapping the contours of an explicitly Black modernity—embodied in objects like the earliest books printed in Africa, paintings by Black Renaissance artists, or the proceedings of free Black institutions in the Americas—and rethinking the writing of history more broadly. Through what he called the “dust of digging,” Schomburg promised not only to situate Black actors at foundational moments of western civilization but also to position the African continent as a pivot of world history. [18] The past, he argued, revealed ways of thinking about blackness and solidarity that rebuked the stranglehold of imperialism and anti-blackness on the present. Thus, for Schomburg, the antiquarian was a crucial and modern figure of Black struggle. To build a library was to help build a movement.

In 1926, at the height of the New Negro Renaissance, Schomburg sold his collection to the New York Public Library. That move—from Schomburg’s parlor to a “great house” of literature—marked the final time he packed or unpacked his library. [19] The widely-heralded sale made him the African diaspora’s most famous collector. But what we now call the “Schomburg Collection,” named for a single individual, came about through “adventures in mutuality.” [20] In acts of acquisition, revaluation, categorization, and display, Schomburg and his friends engaged in both collecting and archive-building. Terms that are related but not synonymous, collecting invokes assembly (which can be whimsical as well as systematic, ephemeral as well as permanent), whereas archive-building implies infrastructure (anticipating future use). [21] It is the entwined nature of these acts that makes archives, in the words of Achille Mbembe, an “instituting imaginary.” [22] In their decisions about what to acquire, and in their pilgrimages to rescue manuscripts, Schomburg and his collaborators imagined: they invented the concept of “Negroana” when it was a “forgotten field.” [23] In their efforts to organize and exhibit their assemblages, they instituted: they created structures for public use. This dual work of imagination and institutionalization characterized Schomburg’s project between 1910 and 1926, a period when, in concert with others, he made a future for Black collecting.

Excerpted from Scattered and Fugitive Things: How Black Collectors Created Archives and Remade History by Laura E. Helton. Copyright (c) 2024 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Laura E. Helton is an assistant professor of English and History at the University of Delaware, where she teaches African American literature, archival studies, and public humanities. She is a co-editor of the digital humanities project “Remaking the World of Arturo Schomburg.” This excerpt is drawn from her book, Scattered and Fugitive Things: How Black Collectors Created Archives and Remade History, published by Columbia University Press in April 2024.

[1] John E. Bruce to Alain Locke, June 5, 1912, box 98, folder 18, Alain LeRoy Locke Papers, (hereafter Locke Papers), Manuscript Division, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University (hereafter MSRC). I refer to Schomburg here as “Arthur” because he corresponded and published under that name (rather than “Arturo,” as he was baptized in Puerto Rico) during in this period. On Schomburg’s cultural migrations, see Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, “The Migrations of Arturo Schomburg: On Being Antillano, Negro, and Puerto Rican in New York 1891-1938,” Journal of American Ethnic History 21, no. 1 (Fall 2001): 3–49. On his diasporic biography, see Elinor Des Verney Sinnette, Arthur Alfonso Schomburg; Black Bibliophile and Collector (Detroit: New York Public Library and Wayne State University Press, 1989); Winston James, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth-Century America (London: Verso, 1998); Lisa Sánchez González, Boricua Literature: A Literary History of the Puerto Rican Diaspora (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 56-69; and Vanessa K. Valdés, Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (Albany: SUNY University Press, 2018).

[2] Arthur A. Schomburg to John W. Cromwell, Labor Day 1912, box 1, folder 14, Cromwell Family Papers (hereafter Cromwell Papers), Manuscript Division, MSRC.

[3] Schomburg to Locke, August 18, 1912, box 83, folder 31, Locke Papers.

[4] Schomburg to Locke, August 18, 1912.

[5] New York State Census for 1915, Enumeration of the Inhabitants of the State of New York, Ancestry.com.

[6] Schomburg to Cromwell, Labor Day, 1912.

[7] [Jack Thorne], “Arthur A. Schomburg,” The Pioneer Press (Martinsburg, WV), September 14, 1912.

[8] “Library of Arthur A. Schomburg. Collection of books on the Negro race, slavery, emancipation, West Indies, South America, and Africa,” n.d., box 13, folder 1, Robert Park Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Fisk University; and Arthur A. Schomburg, “Racial Integrity: A Plea for the Establishment of a Chair of Negro History in Our Schools and Colleges, etc.,” Negro Society for Historical Research Occasional Paper No. 3, (n.p.: August Valentine Bernier, 1913), 12.

[9] “The Negro Society for Historical Research,” African Times and Orient Review, Christmas Annual, 1912.

[10] Negro Library Association, Program for Musical and Literary Evening, June 21, 1918, box 6, reel 3, John Edward Bruce Papers (hereafter Bruce Papers), Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (hereafter SCRBC); and “Grand Concert for Negro Library,” New York Age, May 31, 1917.

[11] “Library of Arthur A. Schomburg.” A partial copy of this same list is preserved on the verso of manuscripts in the Bruce Papers.

[12] Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1968), 67.

[13] Figuras y Figuritas is listed in “Library of Arthur A. Schomburg” among Schomburg’s early holdings; for inscription information see https://legacycatalog.nypl.org/record=b11721021~S67.

[14] Schomburg to Cromwell, October 22, 1912, box 1, folder 14, Cromwell Papers.

[15] Schomburg to Cromwell, July 5, 1912, box 1, folder 13, Cromwell Papers.

[16] William C. Bolivar to Schomburg, n.d., box 1, folder 5, Arthur A. Schomburg Papers, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, SCRBC.

[17] Schomburg to Cromwell, February 23, 1915, box 1, folder 30, Cromwell Papers.

[18] Arthur A. Schomburg, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” Survey Graphic 6, no. 6 (March 1925), 670-71.

[19] Schomburg quoted in Dorothy B. Porter, “Bibliography and Research in Afro-American Scholarship,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 2, no. 2 (1976), 81.

[20] Andrew Ross, “Production,” Social Text 27, no. 3 (2009), 199.

[21] On the terms archive and collection, see Gabrielle Dean, “Disciplinarity and Disorder,” Archive Journal 1, no. 1 (Spring 2011), http://www.archivejournal.net/issue/1/archives-remixed/.

[22] Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, Michele Pickover, Graeme Reid, Razia Saleh, and Jane Taylor (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002): 19-26.

[23] Schomburg quoted in Porter, “Bibliography and Research,” 81.