The Queen of Numbers: Stephanie St. Clair and Harlem's Gambling Racket

By LaShawn Harris

On December 9, 1930, Harlem numbers banker Madame Stephanie St. Clair was released from the workhouse on New York City’s Welfare Island after serving a little over eight months for possession of numbers slips.[1] According to the New York Amsterdam News (NYAN), the forty-something year-old St. Clair emerged from prison and “threw a bombshell in the investigation of the policy racket, police, and Magistrates’ Court when she declared she paid $6,000 to a lieutenant and plainclothes officers.” Commonly known throughout Harlem as the “Numbers Queen,” St. Clair’s release from jail signaled her desire to resume her position as one of Harlem’s preeminent numbers bankers and to contest white gangsters’ attempts at muscling into Harlem’s numbers game. Moreover, St. Clair was hell-bent on exposing law enforcers’ participation in New York City’s illegal multi-million dollar gambling racket.[2]

Harlem’s infamous numbers racket belonged to a global phenomenon of gambling practices that existed at the turn of the twentieth century. Games of chance, including public lotteries, cock and dog fighting, and card playing flourished in cities around the world. But Harlem’s complex racial and ethnic makeup and increasing mass consumerism gave the numbers racket its distinct flavor, setting it apart from other national and international gambling rackets. The highly profitable game attracted many New Yorkers. Needing as little as a penny to play, hopeful players selected numbers between 0 and 999 and placed bets on numbers slips. Numbers runners collected players’ betting slips and delivered bets to the number banker. Numbers bankers financed his / her numbers operation, staffing numbers bank headquarters with a group of controllers, clerks, messengers, and numbers runners.

The “numbers was a people’s game, a community pastime in which old and young, literate and illiterate, the neediest folk and well-to-do all participate. All of Harlem played, from the humble laundrywoman to the disrespectable pool player, as well as the respectable schoolteacher.”[3] For optimistic players, the possibility of “hitting the number” meant additional income for the household. One policy customer explained: “A hit can change a guy’s whole life around. The guy who wins sometimes sets himself up in business, in a grocery store or a bar. Others pay off their bills and some have sent their kids to college.”[4] But not all black New Yorkers took part in numbers gambling. Some black political reformers and ordinary city dwellers frowned upon games of chance, numbers bankers, and the countless players eagerly willing to “take their wearing apparel to pawn shops to play a number.”[5] Black opposition to gambling was rooted in Progressive-era ideas about urban amusements and city spaces. Gambling opponents maintained that games of chance undermined tenets of racial uplift politics that stressed prudence, productive labor, and thrift. Moreover, they posited that games of chance contributed to the demoralization of African American communities.

Madame Stephanie St. Clair was one of few black women to dominate Harlem’s gambling racket during the 1920s and 1930s. Her flamboyant lifestyle and reputation as a dangerous numbers banker captured the imagination of New Yorkers. Born in the mid-1880s or 1890s on the French Island of Guadeloupe and migrating to Harlem in the 1910s, St. Clair established her numbers operation sometime in the early-to-mid-1920s.[6] In a 1938 Afro-American article, journalist Ralph Matthews noted that St. Clair “came to America penniless, unable to speak anything but French. [And] after having made a half-dozen killings” from luck at the numbers racket became a banker.”[7] Another scenario may explain how St. Clair obtained money to launch her business. In 1923, St. Clair filed a lawsuit against her apartment building owner and a City Marshall, claiming she was illegally evicted from her apartment on West 135th street. In her lawsuit, she “claimed that eviction papers by the City Marshall were never served on her” and that her personal items were placed on the street and stolen by bystanders.” Siding with St. Clair, the Seventh District Court rewarded her a judgment of $1,000. Money received from the lawsuit might have been used to finance St. Clair’s numbers bank.[8]

By the 1930s, St. Clair had a “personal fortune around $500,000 cash and [owned] several apartment houses.”[9] Earning an estimated $200,000 a year, she employed forty to fifty numbers runners, ten comptrollers, and several bodyguards and maids, and resided at the exclusive 409 Edgecombe building on Sugar Hill.[10] Living side by side with some of Harlem’s most influential black intellectuals, professionals, and race activists, including National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) activist Walter White, St. Clair did not conceal her occupation nor was she ashamed of her chosen line of work. Her neighbors knew who she was and how she earned a living. In fact, her larger-than-life personality and extravagant lifestyle made her difficult to miss.[11] She was a Harlem luminary; playwright and former 409 Edgecombe resident Katherine Butler Jones recalls that St. Clair was just as fascinating as some of the building’s more “respectable” residents. Butler remembers “Stephanie St. Clair breezing through the lobby with her fur coat. She had a mystical aura about her, and she wore exotic dresses with a colorful turban wrapped around her head.”[12]

The numbers queen caught the attention of the NYPD during the late 1920s. On December 30, 1929, NYPD officers apprehended St. Clair for possession of numbers slips. She was arrested at 117 West 141st Street, where an alleged numbers bank operated. On January 1, St. Clair placed a paid editorial in the NYAN announcing her arrest. “I have been arrested and framed by three of the bravest and the noblest cowards who wear civilian clothes.”[13] During her March 1930 trial, St. Clair, who represented herself, admitted to being a numbers banker, claiming she “was marked for a jail term because of her fight for courtesy and freedom from annoyance [of] the police.” In her nearly three-hour court testimony, St. Clair noted that: “because of her desire to retire after she accumulated her fortune and because of jealousy of other policemen who were not in on the gravy train her apartment was raided, $400 in cash taken,” and she was arrested.[14] Despite St. Clair’s revealing testimony, an unconvinced jury and judge convicted and sentenced her to eight months and twenty days in the workhouse.[15]

Nearly a year later, a vengeful St. Clair emerged from prison determined to disclose the NYPD’s close business ties to numbers racketeers. St. Clair’s personal conflicts with law enforcers and her unwavering determination to unmask urban profiteering placed her in a precarious position. Drawing attention to city malfeasance meant facing possible police retaliation or reprisal from any of the criminal syndicates connected to law enforcement. Regardless of the potential risk, St. Clair appeared before the Samuel Seabury Commission in December 1930. The commission investigated corruption in the Bronx and Manhattan Courts and in the NYPD. Appearing before the commission, St. Clair, lavishly dressed in her mink coat and a chic hat, readily testified about her business relationships with police. According to St. Clair, she “sent payments of $100 and $500 to a lieutenant of the Sixth Division and paid cops a total of $6,000” to avoid arrest.[16] Her testimony resulted in the suspension of thirteen police officers.[17]

White gangster Arthur “Dutch Schultz” Flegenheimer posed the greatest threat to St. Clair. A Bronx native, Schultz was one of New York’s and the nation’s most ruthless bootleggers. In 1935, Federal Bureau Investigations (FBI) director J. Edgar Hoover referred to Schultz as “Public Enemy Number One,” listing him among the most dangerous white criminals of the era.[18] Schultz deployed violent tactics to force African American and Latino numbers bankers out of business. He intimidated non-white numbers barons, offering them several unappealing propositions: Nonwhite bankers could relinquish their successful businesses and work for Schultz or they could continue their operation and pay Schultz a portion of their earnings. If nonwhite bankers rebuffed Schultz’s threatening proposals, they faced potential beatings or murder. St. Clair joined black New Yorkers’ individual and collective resistance against Schultz and other white racketeers who desired to control Harlem’s lucrative numbers racket.

In a 1960 article in the New York Post, St. Clair claimed she was the only “Negro banker” to fight off Schultz, and she criticized black bankers for being intimidated by white racketeers. “I fought Schultz from 1931 to 1935 [and] it cost me a total of 820 days in jail and three-quarters of a million dollars.”[19] St. Clair declared that she was not “afraid of Dutch Schultz or any other living man. He’ll never touch me! I will kill Schultz if he sets foot in Harlem. He is a rat. The policy game is my game. He took it away from me and is swindling the colored people. I’m the only one that’s after him.”[20] Showing her enemies that she was fearless, St. Clair staged several strategies of opposition against white numbers bankers like Shultz. Stepping out of proper images of womanhood and respectability, she employed violence to make a statement about white numbers racketeers’ presence in Harlem. The fiery Numbers Queen confronted some of Harlem’s legitimate white merchants whose establishments served as numbers drops for white racketeers. “She entered their stores one after the other and single-handedly smashed plate glass cases, destroyed policy slips, and ordered the ‘small timers’ to get out of Harlem.”[21] Moreover, St. Clair, inspired in part with 1930s African American merchants and political activists’ “Buy Black” campaigns, encouraged black numbers players to only conduct business with black numbers bankers. In her estimation, white infiltration of Harlem’s numbers racket was an extension of Jim Crow segregation and threatened black bankers’ businesses. Self-interest also motivated St. Clair’s opposition to white numbers bankers. Immigrating to New York with little money and establishing a lucrative business, the fiery banker desired to protect her gambling empire as well as her position within Harlem’s numbers racket.

For interfering with his business operations, Schultz, perhaps viewing St. Clair as someone that ruptured white men’s perceptions of women and challenged white superiority, placed a contract on St. Clair’s life.[22] On October 23, 1935, St. Clair’s public battle with Dutch Schultz ended when he was shot at the Palace Chophouse in Newark, New Jersey. As Schultz lay dying in a New Jersey hospital, he allegedly received a telegram from the “Queen of Numbers,” which read, “As ye sow, so shall you reap.” He died three days later on October 26.

St. Clair remained in newspaper headlines even after the death of Shultz. Local and national newspapers captured the details of her unconventional marriage. In August 1936, forty-nine year-old St. Clair married Sufi Abdul Hamid, a thirty-year-old Harlem race activist and stepladder preacher. St. Clair and Hamid’s contract marriage was a non-legal union. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1903, Hamid, whose real name was Eugene Brown, was an imposing figure who stood six feet tall and weighed 225 pounds. The colorful political reformer was routinely seen on Harlem streets wearing a turban wrapped around his head, a black and crimson lined cape, a green velvet blouse, and black riding boots.[23] Although spectators claimed that St. Clair and Hamid made a fascinating couple, their “whirlwind romance” ended in 1938.

On January 19, 1938, in an office building on 125th Street, St. Clair shot Hamid after accusing him of having an affair with a young “conjure woman from Jamaica.” This “conjure woman” was none other than famed Harlem fortuneteller Dorothy “Fu Fu Futtam” Matthews, whom Hamid eventually married later in April 1938.[24] In her own defense, St. Clair claimed that the gun went off during a struggle between the two former lovers. She informed police that she went to confront Hamid because “he had been treating her cruelly” and because of his alleged affair with Matthews. In several newspaper interviews, Hamid admitted that he was not surprised by her actions. Several weeks prior to the shooting, St. Clair “had threatened his life” after he informed her that he “wanted no more to do with” her.[25] For shooting Hamid, St. Clair was sentenced to two to ten years at the New York State Prison for Women at Bedford.[26]

St. Clair was released from prison during the early 1940s. But the details of her post-prison life are mystery. A 1943 newspaper article reported that St. Clair’s post-prison whereabouts “are not definitely known. Shortly before the start of the war [World War II], she visited relatives and friends in the West Indies. Since then, she has lived in seclusion.”[27] In 1960, an aging St. Clair resurfaced in a newspaper interview conducted by New York Post journalist Ted Poston. Writing about the whereabouts of former 1930s black and Latino numbers bankers, Poston informed readers that St. Clair had successfully transitioned from underworld figure to a legitimate “prosperous business woman.”[28] Mayme Johnson, wife of 1940s Harlem gangster Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson claimed St. Clair relocated to a Long Island mansion “never again getting into the numbers business.”[29] While many early twentieth-century newspapers reported on various aspects of St. Clair’s complex public life, her purported death in 1969 was not mentioned in any newspaper of the era.

Madame Stephanie St. Clair was more than just an underground entrepreneur. The Numbers Queen was a complex woman, shifting at will from criminal to community advocate. Blurring the lines between propriety and criminality, St. Clair took part in ongoing conversations about racial advancement and urban inequality. Her race and political consciousness were grounded in New York’s changing socioeconomic and political landscape, urban blacks’ collective struggle against inequality, and her personal experiences with bigotry. St. Clair’s commitment to racial equality was displayed in the NYAN. Between the late 1920s and early 1930s, St. Clair placed paid opinion pieces in the black newspaper. Her public writings focused on black immigration, city politics, and police brutality. Not one to shy away from controversy, St. Clair defied normative images of early twentieth century black women activists. Her style of community advocacy ushered in alternative expressions of reform. The numbers queen’s distinct style of community work delineated the diverse ways in which black New Yorkers employed informal economies to earn a living and contest urban inequality.

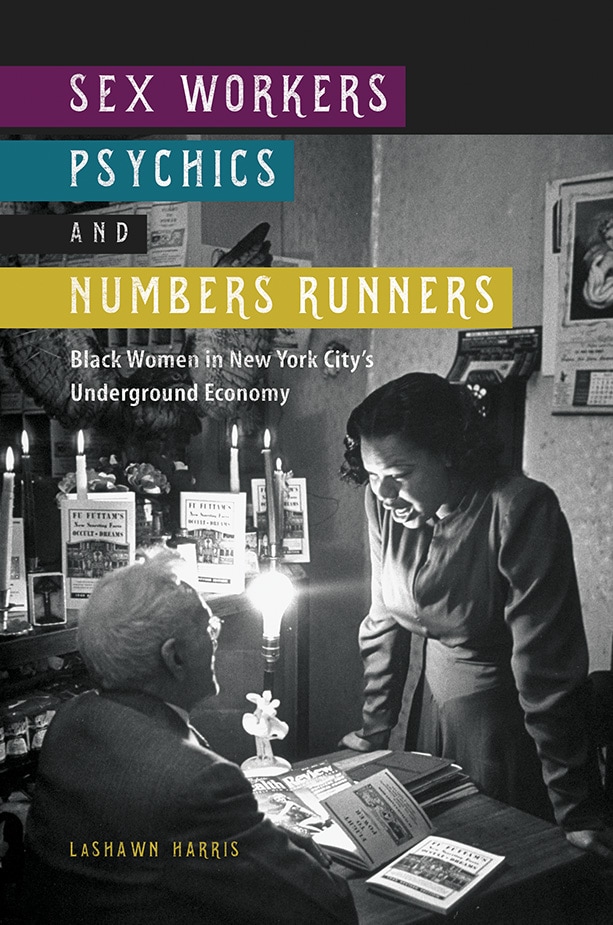

LaShawn Harris is an Assistant Professor of History at Michigan State University. She is the author of Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City's Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016).

[1] Rufus Schatzberg and Robert J. Kelley, African-American Organized Crime, 62; “Mme. St. Clair Bares ‘Policy’ Protection,” New York Amsterdam News, December 10, 1930, 1; Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999), 507–508; Judith Berdy, Roosevelt Island (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 60, 71.

[2] Rufus Schatzberg, Black Organized Crime in Harlem: 1920 –1930 (New York, NY: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1993), 39–40; “Madame Stephanie St. Clair Convicted,” New York Amsterdam News, March 19, 1930, 1; “Mme. St. Clair Bares ‘Policy’ Protection,” New York Amsterdam News, December 10, 1930, 1.

[3] McKay, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, 101.

[4] Fred J. Cook, “The Black Mafia Moves into the Numbers Racket,” New York Times Magazine, April 4, 1971, 112.

[5] “Corruption of Gambling,” New York Age, August 17, 1929, 5.

[6] George Gachette, Petitions for Naturalization, April 3, 1938, Petitions for Naturalization from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1897-1944, ser. M1972; roll 0575, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[7] Ralph Matthews, “Was It Curse of Father Divine or Did Madame St. Clair Kill Sufi?” The Afro-American, August 6, 1938, 3;

[8] “Mme. Gachette Gets Judgment for $1,000,” New York Amsterdam News, February 14, 1923, 3.

[9] T. R. Poston, “Harlem Shadows: Harlem Moon,” Pittsburg Courier, December 27, 1930, 2.

[10] Lawrenson, Stranger at the Party, 175; Butler Jones, “409 Edgecombe, Baseball and Madame St. Clair,” 137; Schatzberg and Kelly, African American Organized Crime, 89; “Graft on Gambling Laid to the Police by ‘Policy Queen,’” 1; Final Report of Samuel Seabury, Referee: Supreme Court, Appellate Division-First Judicial Department (New York, NY: Arno Press, 1974), 137; “Harlem ‘Numbers’ Woman Is Witness in Investigation of Police and ‘Stool Pigeon’ Activities in Greater N.Y.,” New York Age, December 13, 1930.

[11] Harlem ‘Numbers’ Woman Is Witness in Investigation of Police and ‘Stool Pigeon’ Activities in Greater N.Y.,” New York Age, December 13, 1930; Butler Jones, “409 Edgecombe, Baseball and Madame St. Clair,” 132; Christopher Gray, “Streetscapes / 409 Edgecombe Avenue; An Address that Drew the City’s Black Elite,” New York Times, July 24, 1994; “Mrs. Carter Seen as Only Negro Appointee,” New York Amsterdam News, August 10, 1935, 1.

[12] Butler Jones, “409 Edgecombe, Baseball and Madame St. Clair,” 136.

[13] “Display Ad 4 – No Title: Mme. Stephanie St. Clair” New York Amsterdam News, January 1, 1930, 2.

[14] Ted Poston, “Harlem Shadows: Harlem Moon,” Pittsburgh Courier,” December 27, 1930, 2.

[15] “Confessed Banker of Numbers Given Sentence to Island,” New York Amsterdam News, March 19, 1930, 1.

[16] “Mme. St. Clair Bares ‘Policy’ Protection,” New York Amsterdam News, December 10, 1930, 1.

[17] “Harlem ‘Numbers’ Woman Is Witness in Investigation of Police and ‘Stool Pigeon’ Activities in Greater N. Y.,” New York Age, December 13, 1930, 1.

[18] Ray Wannall, The Real J. Edgar Hoover: For the Record (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2000), 173; Timothy W. Bjorkman, Verne Sankey: America’s First Public Enemy (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), 71.

[19] Ted Poston, “Inside the Policy Racket: The Cops Had a Share In the Old Days, Too,” The New York Post, March 4, 1960, 4.

[20] “Harlem Policy Queen Declares War on Rival,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 5, 1935, 6.

[21] Marvel Cooke, “Mme. St. Clair Alone Defied Dutchman,” New York Amsterdam News, August 27, 1938, 1.

[22] Poston, “Inside the Policy Racket,” 4.

[23] Winston McDowell, “Race and Ethnicity during the Harlem Jobs Campaign, 1925–1932,” Journal of Negro History 69 (Summer-Autumn 1984): 138; Wilbur Young, “Activities of Bishop Amiru, Al-Mumin Sufi A. Hamid,” Writers’ Project Program New York, N.Y Collection, 1936–1941, Reel #1, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

[24] Mme. St. Clair ‘Guilty,’” Chicago Defender, March 19, 1938, 1; “Mme. St. Clair Just Wanted Conciliation,” 3; Butler Jones, “409 Edgecombe, Baseball and Madame St. Clair,” 139; McKay, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, 79; “Cult Leader and Pilot Die in Air Crash,” Syracuse Herald, August 6, 1938, 2.

[25] People v. Stephanie St. Clair, filed January 31, 1939, District Attorney’s Closed Case Files (DACCF), Municipal Archives of the City of New York; “$6,000 Bail For Mme. St. Clair,” New York Amsterdam News, January 22, 1938, 1.

[26] Mme. St. Clair Gets Ten Years,” New York Amsterdam News, March 26, 1938, 1; “Plane Crash Fatal to ‘Black Hitler,’” New York Times, August 1, 1938, 1.

[27] D-1970: Stephanie Hamid, Westfield Receiving Blotters / Department of Correction, New York State Archives; Carolyn Dixon, “What’s Happened to the Numbers Game? Check-Up Discloses Interesting Facts,” New York Amsterdam News, December 18, 1943, 24; “MME. St. Clair Not Released,” New York Amsterdam News, April 13, 1940, 1.

[28] Poston, “Inside the Policy Racket,” 4, 20.

[29] Mayme Hatcher Johnson and Karen E. Quinones Miller, Harlem Godfather: The Rap on My Husband, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson (Philadelphia, PA: Oshun Publishing Company, 2008), 115.