The First Cinemas in Black Harlem: A Look at the Silent Film Era, 1909-1926

By Agata Frymus

The history of cinemas in Harlem is as old — or, in fact a few years older — than its history as a lively center of Black life. Movie houses that opened their doors to African Americans in the late 1900s and early 1910s offer a fascinating insight into the history of Harlem’s residents.

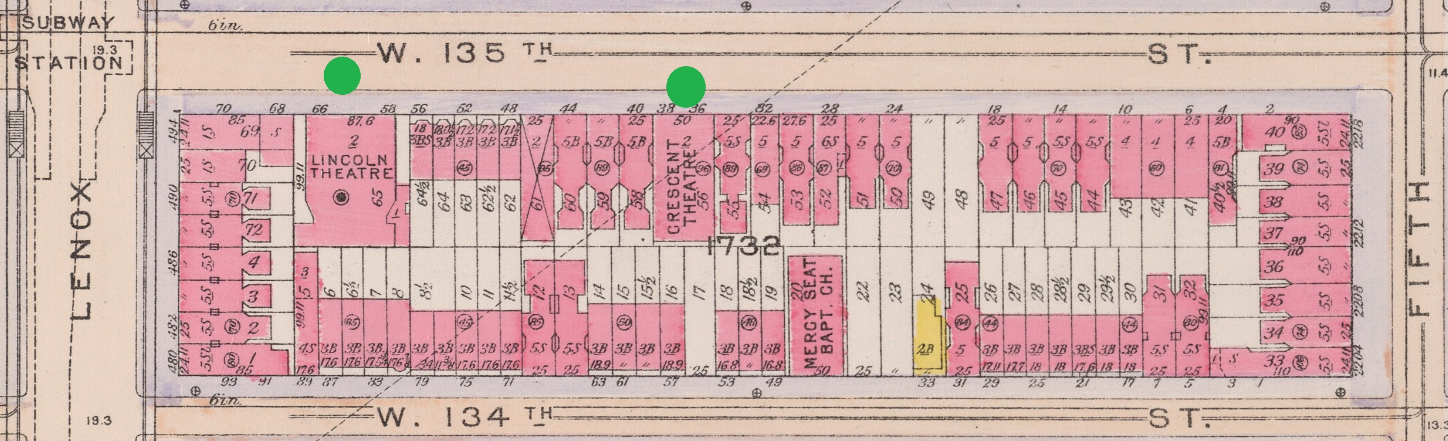

The opening night of the Crescent, on the December 16, 1909 — hailed as a “first class vaudeville and moving picture house” — turned out to be so successful that many patrons had to be turned away.[1] This pioneering cinema stood at 50 W 135th Street. We know that another theater, the Lincoln, situated on the same block, opened around the same time, so competition was fierce from the outset. Scholars do not agree as to which venue was first, but the Lincoln was probably the predecessor (unless it opened in the last 15 days of 1909).

Interestingly, all forms of discrimination — be it racial or religious — were criminalized across New York State in 1909. Yet the practice of relegating African American moviegoers to balcony seating, or simply not allowing them entry, was widespread across the metropolis.

This is the reason why Harlem cinemas are so important, as they openly advertised themselves as theaters oriented toward Black clientele. In attending them, Harlemites could not only watch movies — and sit anywhere they liked — but also listen to Black musicians and enjoy Black theatrical performances. These spaces not only welcomed them, but also celebrated Black talent. The history of cinema going in Harlem is, then, not only a history of film exhibition, but also that of local sociability, demographic changes, and shifts in racial politics. This article looks at some of the first Black cinemas in Manhattan’s famous African American district.

The Lincoln Theatre

Headed by Maria C. Downs, a wealthy New Yorker of Puerto Rican or Cuban descent, the Lincoln had expanded its original operation from a storefront nickelodeon to a theater with a 300-person capacity in 1909.[2] In all likelihood, it was the first Black theater in Harlem, and one of the very first desegregated picture houses in the United States. At the outset, it specialized in moving pictures, but its program soon incorporated blackface and variety performance.[3]

The building that was once Lincoln theatre, as seen in March 2019. Photo by the author.

In 1915, Downs expanded her profile — and profits — by erecting a new building in place of the old one, further increasing the Lincoln’s seating capacity to 850. The bill included a feature film every day, as well as six vaudeville acts that changed twice a week. When the management invested in a resident Black theatrical company in 1915, the programming was enriched by a four-play act presented on a weekly basis.[4]

One of the very few female cinema owners, Downs had astute business acumen, and was quick to recognize the benefits offered by orienting the theater towards a Black audience. This aspiration is reflected in the fact that she got rid of the previous name, Nickelette, and reestablished her business as the Lincoln. At the time, there was a wider trend amongst Black and Black-oriented investors to name venues after heroic white figures that alleviated the African American plight. Naturally, the abolition of slavery made Abraham Lincoln a popular choice. The tendency was additionally underscored by the fact that 1909 marked the centennial of the president’s birth. In the silent movie period, approximately a dozen Black theaters shared his name, operating in locales as distant as Cincinnati, Los Angeles, Jacksonville, Kansas City, Washington DC, Houston and Knoxville.[5]

Jacqueline M. Moore suggests that the naming policy worked in conjunction with the employment of Black managers to create an illusion that the theaters were run by the members of the race, whilst in most cases, they were not.[6] This trend in ownership endured throughout the 1920s, as seventy-five to eighty-one percent of Harlem’s businesses were controlled by whites.[7] Indeed, it seems that white proprietors of the Crescent, Henry Martinson and Benjamin Nibur, used Black men, Thomas Johnson and I. Flugelman, as the spokespeople for their establishment.[8] Hesitant to reveal their identity, the owners shifted the focus to the personae of the Crescent’s two official presidents. Equivalent strategy was demonstrated by businesses in other cities, for example in Washington, where the founders of aforementioned Howard theater used black management as a front, in a way of profiting from ethnic solidarity.[9]

Lincoln and Crescent theatres, as featured on the map from the early 1910s. Fire insurances maps available at New York City Public Library.

Looking back, many moviegoers described the Lincoln’s audience as rowdy and working-class. Perhaps the draw of Downs’ business was captured best by one frequent attendee, who explained that the Lincoln “had movies and short acts for short money.”[10] A writer for The Messenger critic described the Lincoln’s audience in similar terms, observing with horror how Black men and women left chewing gum on the seats and threw peanut shells across the aisles.[11]

The Crescent Theater

A prominent Black film critic, Lester A. Walton described the Crescent as a place drawing a diverse clientele, where “white and colored sat side by side, elbowing each other” and where Black ushers made no attempts to interfere by separating the races.[12] Walton was optimistic: soon enough, he reasoned, all theaters would be prompted to institute equally inclusive policies.

Advertising for a biblical feature Daniel (1913). Was it screened at Crescent? We have no hard evidence, but Vitagraph was a New York-based studio known for its sophisticated productions, so it is likely.

Unfortunately, we know very little about the types of photoplays screened at the Crescent, because most of the publicity and subsequent reviews revolved around the vaudeville show. The only source containing details that go beyond mentioning the simple fact of moving pictures comes in January 1910, with the advert promising “at least one Vitagraph picture daily.”[13] The brevity with which the publicity dealt with the movies was by no means unusual. These one-reel features, which tended to run about fifteen minutes in length, changed so frequently there was little incentive for cinemas to describe them in much detail.

Although the Crescent’s history proved short, as increasing competition drove the owners out of business by 1915, its trailblazing impact on local entertainment was vast.[14] Some historians point out that in staging established, sophisticated productions such as the opera The Tryst, the venue initially aspired to appeal to middle-class customers.[15] Opinion pieces in the local press continuously alluded to its reputation as a bastion of safe entertainment: “When patrons go to the Crescent Theater they expect to see a clean show. Those who want to see a muscle dance exhibition and hear a lot of raw talk know where to go for it.”[16] At a time when moving pictures houses were still fairly new — and perceived as trite, or even vulgar — this was an important statement. In the following decade, the building would house another cinema, the Gem.

The Lafayette Theatre

Opening in 1912 and boasting a capacity exceeding 1400 seats, this theater was able to house more patrons than the area’s existing Black playhouses, the Lincoln and the Crescent, combined. “Before the Lafayette,” reminisced one former resident, “the only theaters open to colored were little dumps.”[17] Situated at the edge of a contemporary Black neighborhood, the venue was designed to attract patronage from both sides of the color line. This dynamic found its reflection in the first night, when — as one magazine recounted years later — managers looked around to see which race dominated the crowd. They were then to decide whether the operation should be a white or a “colored” one.[18]

Lafayette in 1936. Photograph from the Library of Congress.

While this story is likely apocryphal, it does accurately reflect the Lafayette’s spatial and social liminality. Initially, the Lafayette’s discriminatory policies fell short of fulfilling its proclaimed mission of “providing a place of amusement for the race.”[19] The management welcomed only “respectable” Blacks, which in practice meant that any Black individuals could be relegated to inferior seating in the balcony based on the personnel’s whims. Who counted as “respectable” and who did not was arbitrary, causing an understandable stir in the black neighborhood. After six months, Lafayette banished the procedure that cost it both bad press and a substantial loss of profits.

The Gem Theatre

Gem opened sometime in 1925, at the dawn of the silent film era. Contrary to big movie houses, it rarely advertised in the Black press, relying purely on local trade. For that reason, its history and programming are difficult to retrace. The fact that the Gem was a Black theater, however, is beyond doubt. In spring 1926, the Association of Colored Motion Projectionists ran an ad in one of Harlem’s weeklies, announcing that the Gem, as well as the Renaissance and Lafayette theaters, would now all employ Black staff.[20] The union had worked in conjunction with Black journalists, putting pressure on Black-oriented businesses to hire African Americans. As always, people of color paid inflated prices to realize their ambitions. The doors of white cinemas were closed to Black projectionists while “the world remained wide open” to whites.[21]

A scene from Ten Nights in a Barroom (1926). The film was adapted from a pro-prohibition novel of the same title. Earlier screen versions included a Thanhouser one-reel picture from 1910.

The following year, the Gem screened a race movie, Ten Nights in the Barroom (1926) starring the Black actor Charles Gilpin.[22] Interestingly (and unlike most silent features) the film survives to this day. It tells the story of Joe Morgan, a man living in the small town of Cedarville, whose life has been ruined by his alcohol dependency. Told in flashback, Morgan’s downward spiral is paralleled by the slow degradation of his hometown. By the end of the film, Morgan is determined to save the locals from vice and campaigns for prohibition.

An acclaimed stage actor, Gilpin was certainly a big draw. His accomplishments in the arts were so vast he could not be ignored even by the white circuits. In 1920, the actor became the first African American honored with the Drama League’s annual award. One year later, his theatrical career catapulted him to the highest echelons of society, when he was invited to a private audience in the White House. Apparently, he discussed “the uplift of the colored race” with President Warren G. Harding.[23]

“Notice to the Public,” New York Age, April 3, 1926, 6.

Most of Harlem’s small-scale theaters were affected adversely by the introduction of talkies in the late 1920s and then by the onset of the Depression. After more than twenty years in the business, in 1929, Downs sold the Lincoln to another entrepreneur, Frank Schiffman.[24] The Gem closed its doors sometime around 1935. The Lafayette, which was always more of a live performance venue than a cinema, survived until the 1950s, when it was converted into a church. It was demolished in 2013, a great loss to Harlem’s history. Cinemagoing of yesterday — and its magnificent buildings — are, in most cases, nothing more than a memory.

Agata Frymus, PhD, is a film historian and a Lecturer in Film and TV at Monash University, Malaysia. She is the author of Damsels and Divas: European Stardom in Silent Hollywood (Rutgers University Press, 2020).

[1] Lester A. Walton, “Crescent Theatre Has Big Opening,” New York Age, December 23, 1909, 6.

[2] Interestingly, Downs herself had some experience as a vaudevillian. Under her maiden name, Godoy, she also recorded what is now considered some of the very first Spanish-language songs made in the United States. See William A. Everett and Paul R. Laird, The Cambridge Companion to the Musical (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 71.

[3] Morgan, “The Lincoln Theatre,” New York Age, June 12, 1920, 6.

[4] Richard Newman, ‘The Lincoln Theatre,’ American Visions 6, August 1991, 29.

[5] Tom Davin, “Conversation with James P. Johnson,” Voices from the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Nathan Irvin Huggins (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 327.

[6] Jacqueline M. Moore, Leading the Race: The Transformation of the Black Elite in the Nation’s Capital (Charlottesville and London: University press of Virginia, 1999), 59.

[7] Stephen Robertson, “Constrained but not Contained. Patterns of Everyday Life and the Limits of Segregation in 1920s Harlem,” in The Ghetto in Global History: 1500 to the Present, ed. Wendy Z. Goldman and Joe William Trotter Jr. (New York: Routledge, 2018): 223-237.

[8] Lester A. Walton, “Theatrical Comment,” New York Age, January 19, 1911, 6.

[9] Moore, Leading the Race, 59.

[10] “Lincoln” in The African American Theatre Directory, 1816-1960: A Comprehensive Guide to Early Black Theatre Organizations, Companies, Theatres, and performing Groups, ed. Bernard L. Peterson, Jr. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1997), 125. Houston also had a theatre named after Lincoln. See “Doings of the Race,” New York Age, April 6, 1916, 6.

[11] Theopilius Lewis, “Theatre,” Messenger, December 1924, 380.

[12] Lester A. Walton, “Mission of Crescent Theatre,” New York Age, January 6, 1910, 6.

[13] Crescent Theatre Advert, New York Age, January 6, 1910.

[14] Aberjhani, “Crescent Theater,” Encyclopaedia of the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Aberjhani and Sandra L. West (New York: Facts on File, 2003), 74.

[15] Anthony D. Hill and Douglas Q. Barnett, A to Z of African American Theater (Lanham, Toronoto, Plymouth: Scarecrow Press, 2009), 121.

[16] Lester A. Walton, “Theatrical Comment,” New York Age, July 18, 1912, 6.

[17] Francis’ Doll Thomas was born in 1893. She was interviewed by Jeff Kisseloff in his You Must Remember This: An Oral History of Manhattan from the 1890s to World War II (Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, 1989), 276.

[18] “We Are Still Going Down the Memory Lane and Recalling the Good Old Times,” New York Amsterdam News, July 22, 1925, 6.

[19] “The W-H-C Theatre,” New York Age, March 28, 1912, 6.

[20] “Notice to the Public,” New York Age, April 3, 1926, 6.

[21] Cited in Shannon King, Whose Harlem Is This Anyway?: Community Politics and Grassroot Activism During the New Negro Era (New York and London: New York University Press, 2017), 85.

[22] Gem Theatre Advert, New York Amsterdam News, November 30, 1927, 13.

[23] Charles John G. Monroe, ‘Gilpin and the Drama League Controversy, Black American Literature Forum, vol. 16, no. 4, Black Theatre Issue (Winter, 1982): 140.

[24] “Schiffman Leads the Amusement World,” New York Amsterdam News, April 24, 1929, 12.