“In Any Character Except that of a British Subject”: The Staten Island Diplomatic Peace Conference of 1776

By Phillip Papas

“I received your Favour of the 16th. I did not immediately answer it, because I found that my Corresponding with your Lordship was dislik’d by some Members of Congress,” Benjamin Franklin wrote to Admiral Richard Lord Howe on September 8, 1776. “I hope now soon to have an Opportunity of discussing with you . . . the Matters mention’d in it.” Franklin informed the British admiral that he had been appointed by the Continental Congress to a delegation with John Adams and South Carolina’s Edward Rutledge to meet with him as private gentlemen, regarding the War for Independence. [1] The British invasion of North America had begun two weeks earlier, in New York.

The delegates departed Philadelphia the next morning and arrived in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, on September 10th. Admiral Howe sent the Americans a note indicating that he would meet with them “at the house on Staten Island opposite to Amboy,” the home of Colonel Christopher Billopp. [2]

On September 11, 1776, under a flag of truce, Adams, Franklin, and Rutledge met with Howe in a brief and informal yet pivotal diplomatic conference to discuss the potential for peace at the start of the war. It is a moment that is largely overlooked in the broader narrative of the American Revolution. The conference strengthened Congress’s resolve and caused rebel leaders to fully commit to war against Britain. What follows is an account of how that meeting came about —and why it was doomed to failure.

***

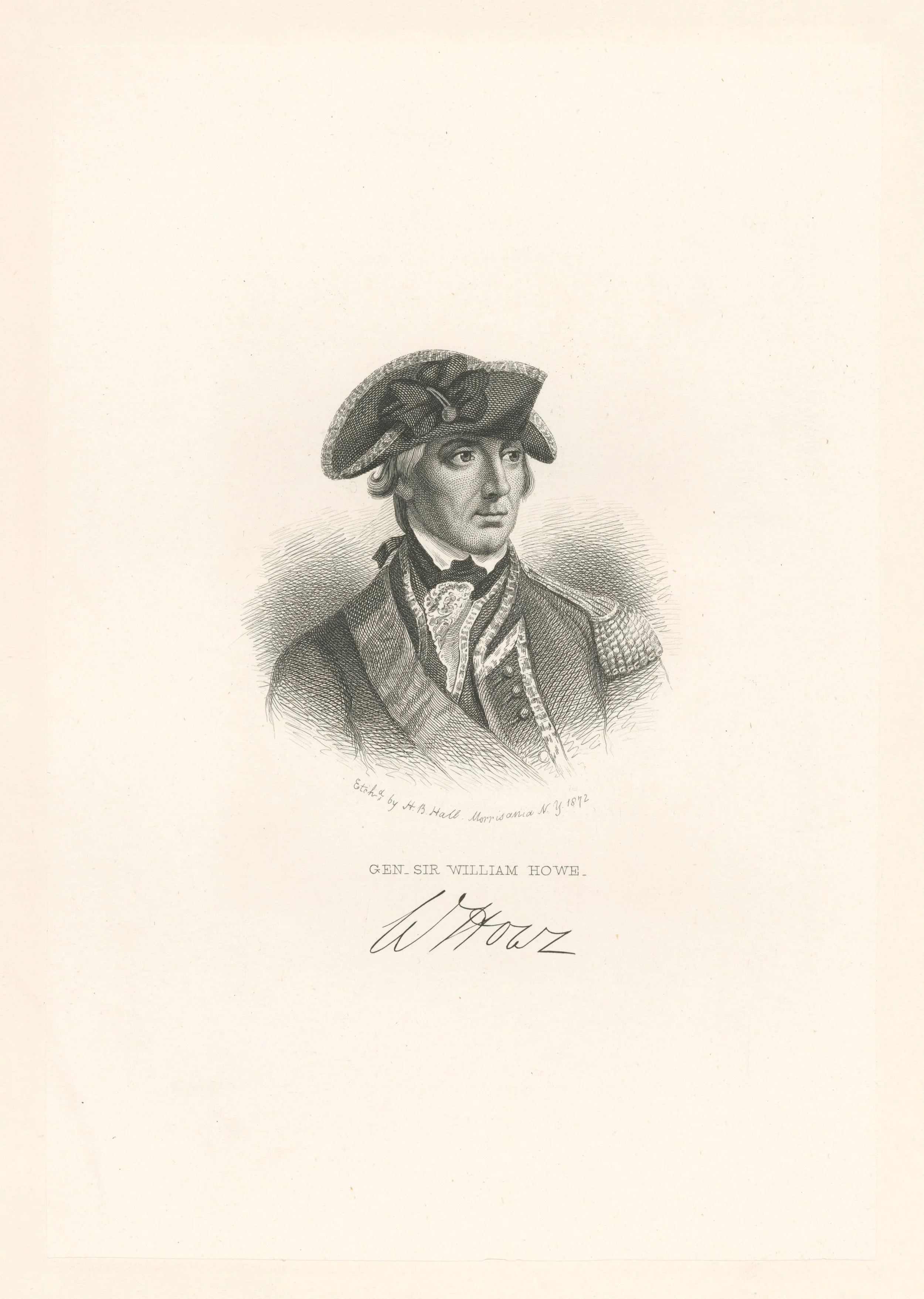

American troops had besieged the British military in Boston for almost 11 months after the “first shot” of the Revolution was fired on the green in Lexington. On March 17, 1776, believing their position untenable, General William Howe, the commander of the British Army in North America and the younger brother of Admiral Howe, evacuated to Halifax, Nova Scotia. There, he waited for reinforcements and contemplated an offensive against New York.

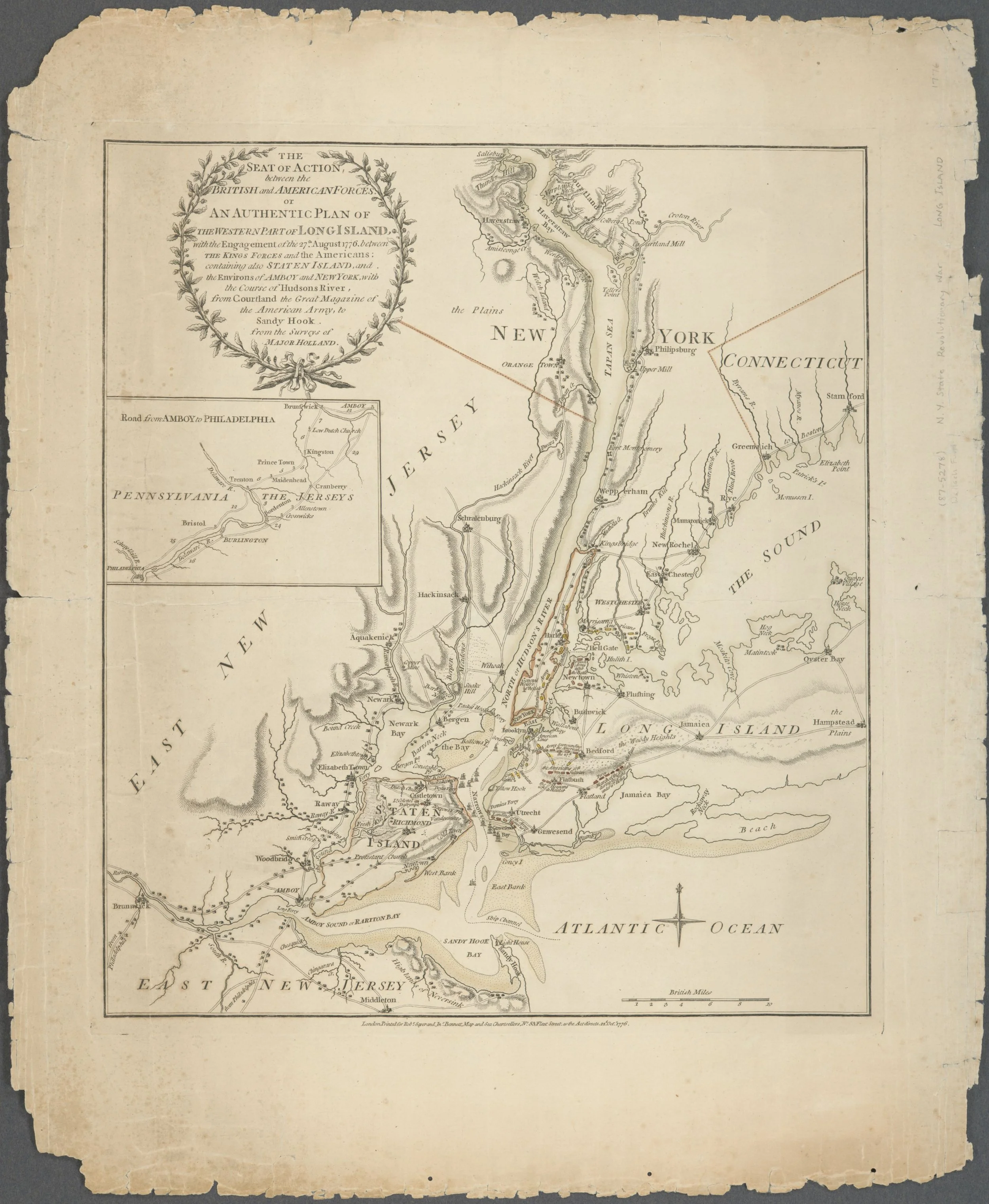

General Howe wanted to start the campaign in April or May. He was delayed by the wait for reinforcements. On June 12, he ordered his forces to sail for New York, and on June 29, the British fleet — 113 ships carrying 9,000 British troops — arrived off Sandy Hook, New Jersey. After two days, Howe chose to land his forces on Staten Island, a loyalist stronghold. On July 2, the British disembarked, wholly unopposed. The last of Howe’s troops landed on July 4, just as the Continental Congress was declaring American independence. [3]

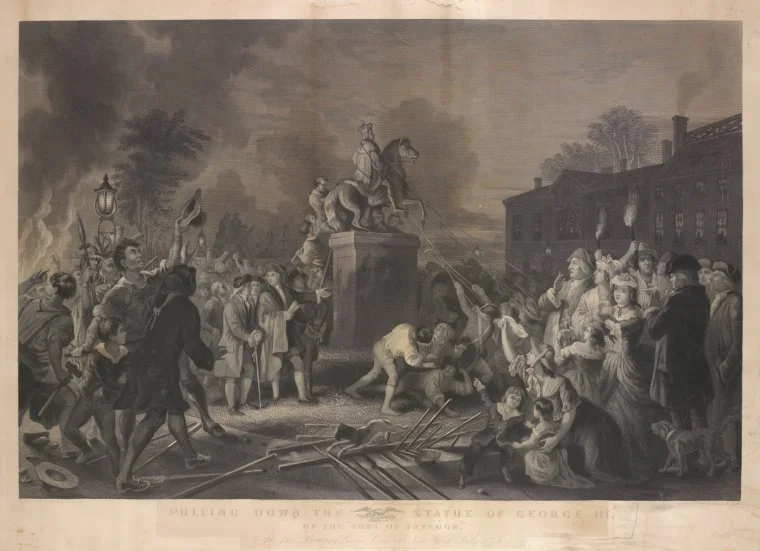

Five days later, the Declaration of Independence was read on the common (today’s City Hall Park) in New York. That night, a group of soldiers and seamen toppled the giant statue of King George III in Bowling Green, to a boisterous crowd. Similar celebrations took place in many communities across the colonies. General Howe realized the situation had become more critical.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library, "Pulling down the Statue of George III by the "Sons of Freedom" at the Bowling Green, City of New York July 1776," New York Public Library Digital Collections, Accessed December 7, 2025, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/38675bc0-c5f0-012f-4f1f-58d385a7bc34.

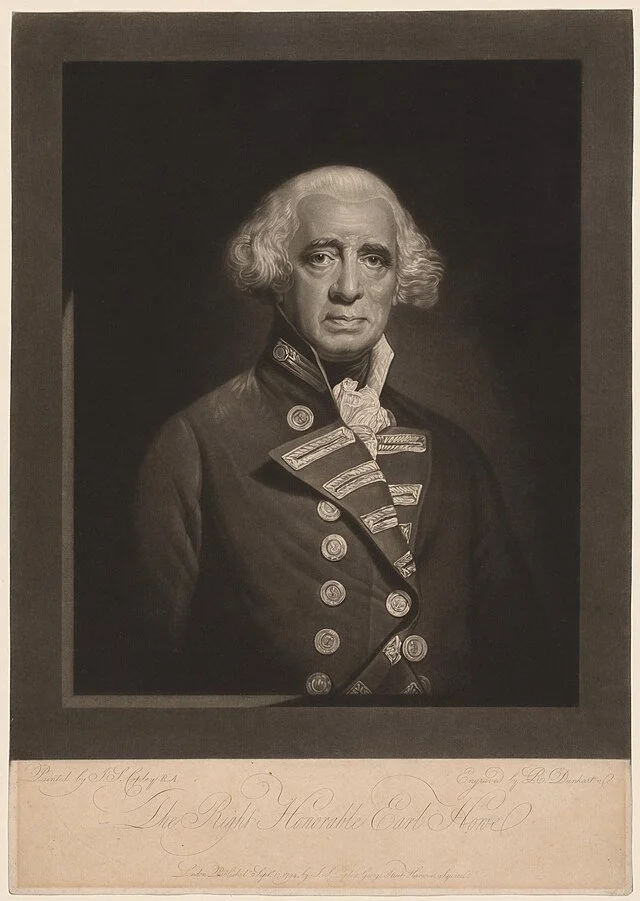

On July12, Admiral Howe’s flagship, the HMS Eagle, appeared in New York Bay ahead of an even bigger fleet: 150 vessels, including ten large warships, 10,000 sailors, and 11,000 soldiers and Royal marines. His arrival was delayed by protracted discussions in London, regarding his appointment as a peace commissioner, which took months to define. Lord George Germain, the British official in charge of the war effort and the secretary of state for America, eventually conferred the title of peace commissioner on both Howes. But he gave them no authority to make political concessions. [4]

Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, "View of the Narrows between Long Island & Staten Island with our fleet at anchor & Lord Howe coming in—taken from the height above the Waterg. Place Staaten Island, 12th July 1776," New York Public Library Digital Collections, Accessed December 7, 2025, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b90c8f60-c6f3-012f-f890-58d385a7bc34.

The Howe brothers met aboard the Eagle. After exchanging salutations, the admiral informed the general of the dual appointment, as peace commissioners — and as commanders of the North American military. William responded with news, to Richard, of the Declaration of Independence. [5]

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library, "Gen. Sir William Howe" New York Public Library Digital Collections, Accessed December 7, 2025, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/3f3856f0-c60a-012f-284a-58d385a7bc34.

Robert Dunkarton, Richard, Earl Howe - 1951.403, Cleveland Museum of Art, 1794, Wikimedia Commons, Accessed December 7, 2025.

The Howes had served in North America during the French and Indian War (1756-63), along with their eldest brother, George, who was killed near Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga). After his death, the Massachusetts Assembly appropriated funds for a memorial in Westminster Abbey, and the younger brothers never forgot this act of kindness. Politically, the Howes identified with the Whigs, the more liberal and dominant party in Parliament. They were also largely supportive of the colonists’ rights (or “liberties”). They had even urged the government to avoid armed confrontation. As an MP from Nottingham, William had opposed taxation of the Americans, too. Although they had to reconcile their personal feelings with their duty to king and country, that summer in 1776 they hoped that reconciliation without further bloodshed was still possible. [6]

In late June, Admiral Howe issued a proclamation from aboard the Eagle off the coast of Massachusetts, calling for an end to hostilities and offering pardons to anyone who swore allegiance to the king. [7] After his arrival in New York, he took the initiative to open a dialogue with General George Washington, who had been in the area since April, overseeing the city’s preparation for the British invasion. On July 13, the admiral sent a letter to Washington via a courier, Lieutenant Philip Brown, announcing his role as a peace commissioner, with instructions from George III and the British ministry to negotiate a reconciliation. [8]

Brown’s vessel was stopped halfway to Governors Island by a Continental Army patrol. [9] Colonel Samuel Blachley Webb, one of Washington’s aides, noted later that Howe’s letter was addressed to “George Washington Esqr.,” and that “on acct. of its direction, we refused to Receive [it], and parted with the usual Compliments.” [10] The inability to address Washington by rank captured the essence of the peace commission’s conundrum. The Howes’ instructions explicitly prohibited them from treating the Continentals as equals or even from negotiating with them until after they had surrendered – since they were British subjects, in rebellion.

The decision to reject the letter was not simply about etiquette, but respect. “I would not upon any occasion sacrifice Essentials to Punctilio,” Washington explained to John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress, “but in this Instance . . . I deemed It a duty to my Country and my appointment to insist upon that respect which in any other than a public view I would willingly have waived. Nor do I doubt but from the supposed nature of the Message and the anxiety expressed they will either repeat their Flag or fall upon some mode to communicate the Import and consequence of It.” [11]

Congress praised the way Washington handled the situation, passing a resolution that strongly approved of his refusal, adding that “no Letter or Message be received on any Occasion whatsoever from the Enemy, by the Commander in Chief or others the Commanders of the American Army but such as shall be directed to them in the Characters they respectively sustain. [12]

As Washington predicted, the Howes tried to engage him again. On July 16, General Howe sent a letter addressed to “George Washington, Esq., etc. etc. etc.” in response to a note regarding the treatment of prisoners from the disastrous American military invasion of Canada. Washington again refused to accept the letter. Undeterred, the Howes tried a different approach. On July 19, Captain Nisbet Balfour sailed to Manhattan to deliver a message asking if Washington would be open to meeting with Lieutenant Colonel James Patterson, one of General Howe’s highly respected adjutants, to discuss an exchange of prisoners. Balfour noted that “there appeared an insurmountable obstacle between the two Generals, by way of Corresponding” before saying that “General Howe desired his Adjutant General might be admitted to an interview with his Excellency General Washington.” The Continental Army officers accepted, and the meeting between Washington and Patterson was scheduled for the next afternoon. [13]

At noon on July 20, the same officers were carried by boat to meet Patterson off the southern end of Manhattan, near Fort George and the Battery. They took the British officer into their vessel and after returning to Manhattan “escorted him safely . . . to Col. Knox’s Quarters” at No. 1 Broadway, across from Bowling Green. [14] The Howes had briefed Patterson to refer to Washington as “His Excellency,” to treat him with respect, and to assure him that they had been granted broad powers as peace commissioners. [15]

After exchanging pleasantries, Patterson “entered upon the Business by saying That Gen. Howe had much regretted the Difficulties which had arisen respecting the Address of the Letters to Genl. Washington” and emphasized that “Ld. Howe & Gen. H. did not mean to derogate from the Respect or Rank of Genl W. – that they held his Person & Character in the highest Esteem.” He then placed a letter addressed to “George Washington, Esq., etc. etc. etc.” on the table. Washington refused to receive it because of the etc. after his name. Patterson explained that “the Addition . . . implied every thing that ought to follow,” to which Washington replied that “it was true the &c. &c. &c. implied every thing & they also implied any thing.”

The British officer shifted the conversation to the treatment of prisoners and a potential prisoner exchange before affirming that the “Goodness and Benevolence” of George III had “induced him to appoint Ld. Howe & Gen. H. as his Commissioners to accommodate this unhappy Dispute.” Patterson declared that the Howes had been granted liberal powers to negotiate a settlement and “would derive the greatest Pleasure from affecting an Accommodation.” He hoped “this Visit” was considered as “making the first Advances to this desirable Object.” [16]

Washington responded curtly that Congress had not granted him “any Powers” to discuss reconciliation. Moreover, he pointed out that George III’s generosity was connected to American capitulation and, although the Howes were called peace commissioners, they had no authority to do much beyond grant pardons. Washington then declared “those who had committed no Fault wanted no Pardon.” The Americans were simply defending their “indisputable Rights.” [17] As early as April, when rumors surfaced that Britain was sending peace commissioners to America, Washington expressed skepticism, believing that British peace overtures were intended to “distract, divide, & create as much confusion as possible.” By July, his opinion had not changed. The meeting ended after one hour, Washington graciously inviting Patterson “to partake of a small Collation provided for him.” The British officer “politely declined” the offer alleging that he had eaten a late breakfast, thanked Washington, and was escorted back to his barge. [19]

With peace overtures going nowhere, the Howes hoped a decisive military victory would compel the rebels to negotiate. By late August, the British had amassed on Staten Island and the harbor around it the largest expeditionary force until D-Day in World War II: roughly 32,000 British Regulars, marines, and sailors, German-allied troops largely from Hesse-Cassel, Loyalist soldiers, and 450 naval vessels. [20] On August 22, they began to move across the Narrows to Long Island, landing at Gravesend in southwestern Kings County (today Brooklyn) — again unopposed, most of the area being predominantly Loyalist, or at least neutral and willing to accept British rule.

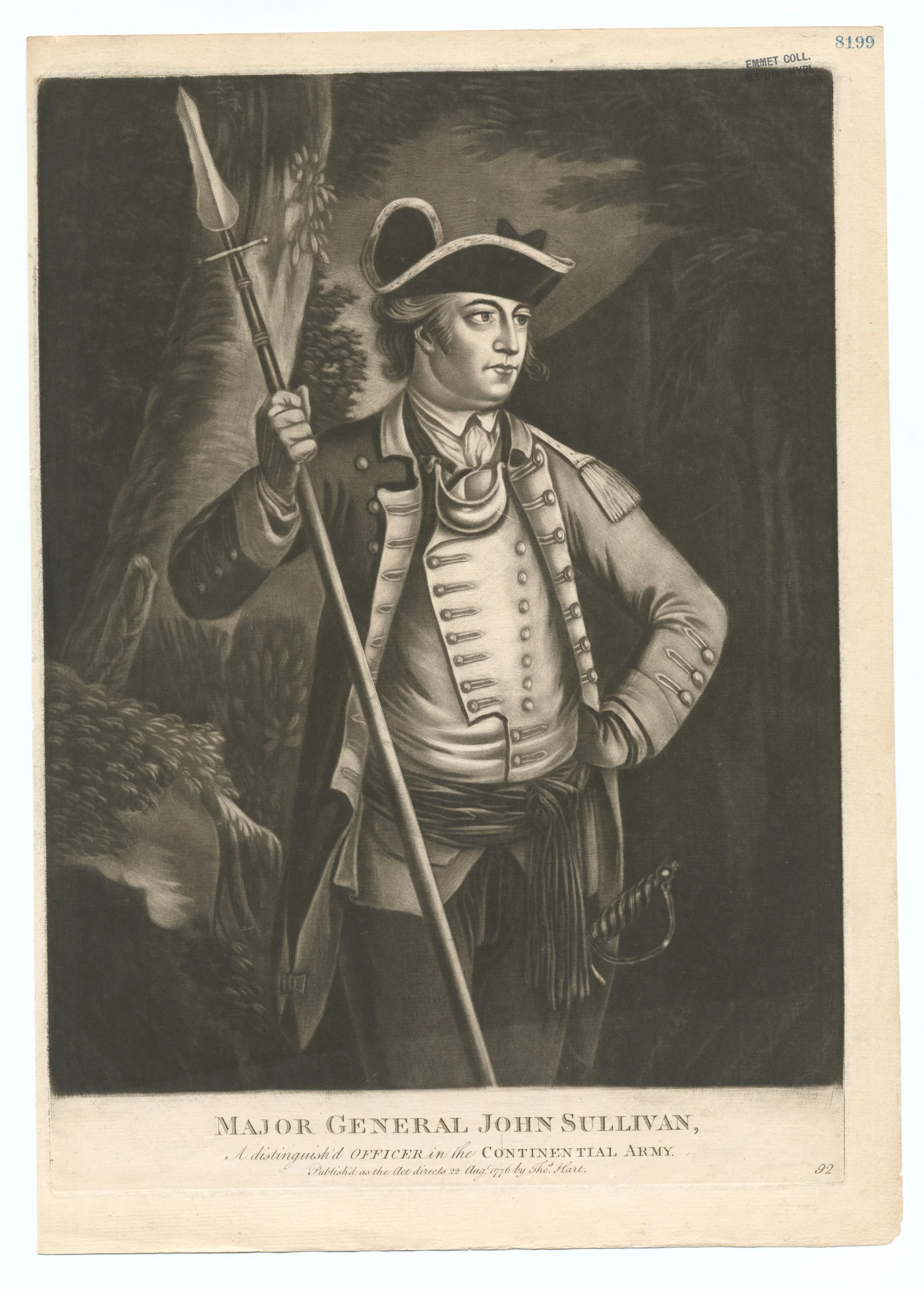

Four days later, the vanguard of the British Army, 10,000 troops, marched freely along the Jamaica Pass, a lightly defended road heading into largely neutral Queens, seven miles east of the Continental lines in what is today central Brooklyn. The next morning, thousands of British troops outflanked the American defenses, causing panic and flight. It was the first major battle of the American Revolution and would remain the largest. But it ended in a rout. Roughly 1,200 Continentals were killed, wounded, or captured. Among the prisoners were three generals: William Alexander (aka Lord Stirling), John Sullivan, and Nathaniel Woodhull.

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.,"The seat of action between the British and American forces: or An authentic plan of the western part of Long Island, with the engagement of the 27th August 1776 between the King[']s forces and the Americans: containing also Staten Island, and the environs of Amboy and New York, with the course of Hudsons River, from Courtland, the great magazine of the American Army, to Sandy Hook," New York Public Library Digital Collections, Accessed December 7, 2025, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6dfdc780-c5aa-012f-c7ea-58d385a7bc34.

Yet General Howe failed to follow up this early, overwhelming success with any decisive action, which might have put an end to the Revolution just a few weeks after the rebels declared Independence. Pinned in Brooklyn Heights, Washington took advantage of Howe’s delay by ordering what remained of the Continental Army to cross the East River that night in flatboats, aided crucially by a heavy fog that blinded the British fleet in the harbor, and the skilled seamanship of the regiment from Marblehead, Massachusetts, commanded by Colonel John Glover. [21]

Although the Howes failed to end the Revolution in Brooklyn (at the so-called Battle of Long Island), they continued to believe that peace was possible without further bloodshed. Admiral Howe gave one of the captured Continental officers, General John Sullivan, a parole to travel to Philadelphia to deliver a message asking the Continental Congress for a meeting. Howe had convinced Sullivan that his commission empowered him to offer generous terms “to compromise the dispute between Great Britain and America upon terms Advantageous to both; the Obtaining of which delayed him near two months in England, and prevented his Arrival at this place, before the declaration of Independency took place.” He offered to receive a delegation from Congress, but only as private individuals. Sullivan presented Howe’s message to Congress and reported that it was the admiral’s opinion “that Parliament had no right to tax America or meddle with her internal Polity” and that George III and his ministers were now open to such an arrangement once hostilities ended. [22]

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library, "Major General John Sullivan" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed December 27, 2025, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/2f4a7640-c60a-012f-81a5-58d385a7bc34.

John Adams was furious. He accused Admiral Howe of manipulating Sullivan into delivering “the most insidious, ’tho ridiculous message,” which “has put Us, rather in a delicate Situation, and gives Us much trouble.” [23] Benjamin Rush, a delegate from Pennsylvania, said Adams called Sullivan “a decoy duck, whom Lord Howe has sent among us to seduce us into a renunciation of our independence.” [24] Benjamin Franklin was equally adamant that at this point there was no turning back from the Declaration of Independence. [25] On September 5, Congress passed a resolution that read: “this Congress, being the Representatives of the free and independent States of America, cannot with propriety send any of its members, to confer with his Lordship in their private Characters.” But “ever desirous of establishing peace, on reasonable terms, they will send a Committee of their body, to know whether he has any Authority to treat with persons, authorized by Congress for that purpose in behalf of America.” [26] Howe could refuse to meet with the American delegation, thereby assuming responsibility for any diplomatic failure, or he could meet with them but acknowledge that he had no authority to negotiate peace terms with representatives from the Congress in any official capacity. In either case, the peace commission would be exposed as a chimera.

Congress appointed John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Edward Rutledge to meet with Admiral Howe. They were prominent, well-respected figures known for their intelligence and commitment to the American cause, ensuring that the American position on independence would not be compromised. Further, each delegate represented a distinct colonial region: Adams of Massachusetts for New England, Franklin of Pennsylvania for the Mid-Atlantic, and South Carolina’s Rutledge for the South, demonstrating a united front. Congress was skeptical that the conference would amount to anything substantial, but saw it as an opportunity to temporarily halt the British advance in New York. Its instructions to the delegation were clear: “to ask a few Questions, and take his [Howe’s] Answers.” [27]

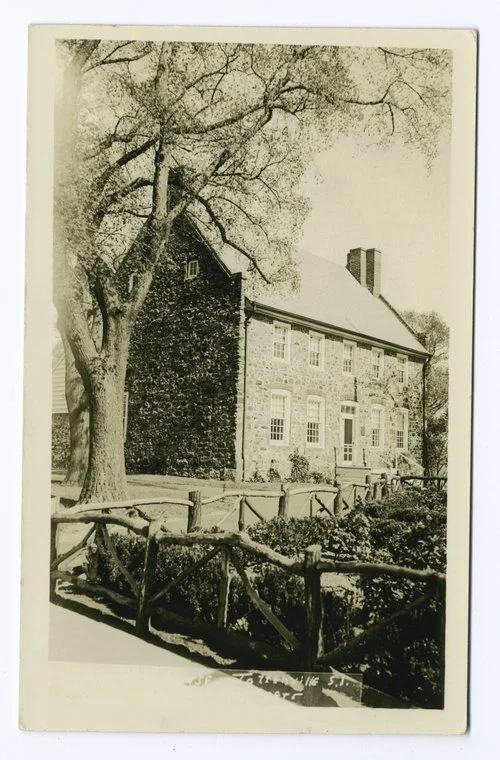

On September 8, Franklin wrote to Admiral Howe informing him of the appointments and asking him to choose a site for the discussions. [28] The meeting occurred on September 11, 1776, at the Billopp house in Staten Island across the Raritan Bay from Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Admiral Howe hoped that the military defeat on Long Island had led the Americans to reassess their prospects for independence. The American delegation was determined to convince him otherwise. [29]

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library, "Conference House" New York Public Library Digital Collections, Accessed December 27, 2025, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6e806aa0-c5ee-012f-d941-58d385a7bc34.

***

On the day of the meeting, Admiral Howe sent a barge to Perth Amboy to carry the American diplomats to Staten Island and ordered a British officer to remain behind to assure their safe return. Adams insisted that no hostage was necessary, saying the admiral’s words were more than sufficient guarantee for their safety. [30] Adams and Rutledge had never met Howe, but Franklin had been well acquainted with him since Christmas Day in 1774, when the two were introduced by Howe’s sister Caroline. Franklin often played chess with Caroline at her London residence and their frequent matches served as a front for secret talks between her brother and Franklin about colonial grievances and potential terms for reconciliation. Although nothing resulted from these discussions, both men came to respect one another. [31]

Howe escorted the Americans to the house “between Lines of Guards of Grenadiers, looking as fierce as ten furies, and making all the Grimaces and Gestures and motions of their Musquets with Bayonets fixed,” wrote Adams, “which I suppose military Ettiquette requires but which We neither understood nor regarded.” [32] The house was owned by Colonel Christopher Billopp, the largest landowner on Staten Island and a former member of the New York Assembly who commanded Billopp’s Corps, the local loyalist militia. It had been commandeered for use as barracks for Hessian troops and, according to Adams, was “as dirty as a stable.” [33] But Howe did his best to make the house presentable and had “a large handsome Room” prepared for the meeting “by spreading a Carpet of Moss and green Spriggs from Bushes and Shrubbs . . . till he had made it not only wholesome but romantically elegant.” He also had a lunch of “good Claret, good bread, Cold Ham, Tongues, and Mutton” prepared for his guests. [34]

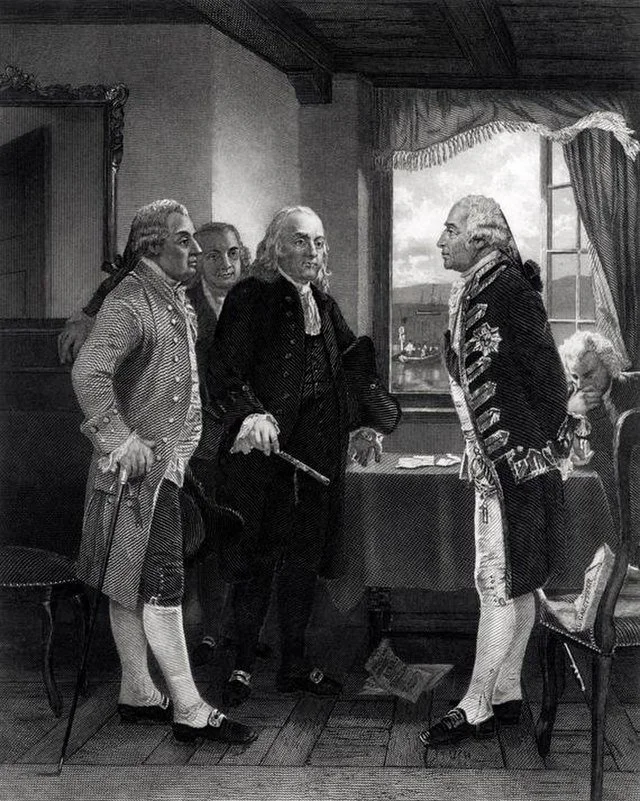

Staten Island Conference by Alonzo Chappel., Depiction of the 1776 Staten Island Peace Conference. On the right stands Admiral Richard Lord Howe. On the left, John Adams, Edward Rutledge, and Benjamin Franklin. Unknown date, Wikimedia Commons, Accessed on December 27, 2025.

After the meal, Admiral Howe reiterated his sincerity as a “Well Wisher to America —particularly to the Province of Massachusetts Bay, which had endeared itself to him by the very high Honors it had bestowed upon the Memory of his eldest Brother.” [35] He expressed a deep affection for the British colonials and declared that “if America should fall, he should feel and lament it like the Loss of a Brother.” To which Franklin replied wryly: “My Lord, We will do our Utmost Endeavors, to save your Lordship that mortification.” [36] The admiral reiterated that debate over his powers as a peace commissioner had delayed him for several weeks, which caused him to arrive in the British colonies shortly after they declared Independence. He emphasized that “he had not, nor did he expect to have, Powers to consider the Colonies in the light of Independent States” and asked “whether there was any probability, that America would return to her Allegiance” to Britain. The Americans replied “that all former Attachment was obliterated. [37]

Interview between Admiral Lord Richard Howe and American Commissioners —Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Edward Rutledge —near Tottenville, Staten Island, Sept. 11, 1776. John Ward Dunsmore, Guarantee and Trust Co., New York, January 1 1911, New York State Archives, Instructional lantern slides, ca. 1856-1939, Series A3045-78, No. 689, Accessed on December 30, 2025.

Adams reminded Howe that the “humble petitions” which the colonists had sent to George III and to Parliament, begging for recognition of sovereignty over taxation and domestic affairs “had been treated with Contempt, and answered only by additional Injuries.” [38] Purportedly, he added that the decision to declare independence was not made in haste. The Americans had demonstrated “Patience” with a long series of transgressions dating back thirteen years, to 1763. He explained that Congress had not “taken up upon their own Authority . . . to declare the independency.” Rather, “they had been instructed so to do, by all the Colonies – and that it was not in their power to treat otherwise than as independent States.” [39]

Visibly frustrated, Admiral Howe reiterated that he did not have the authority to recognize the colonies as independent, nor could he treat his guests as official representatives of Congress. He preferred to “consider them merely as Gentlemen of great Ability, and Influence in the Country” to which Adams remarked that “he had no objection to Lord Howe’s considering him, on the present Occasion . . . in any Character except that of a British Subject.” [40] Howe turned to Franklin and Rutledge and, with a hint of “gravity,” retorted “Mr. Adams is a decided Character.” [41] (Years later, when serving as the U. S. ambassador to England, Adams was told that Admiral Howe had been given a list of names of Americans who “were expressly excepted . . . from Pardon, by the privy Council” and that he was one of them. [42])

Rutledge then asked if Britain “would not receive greater Advantages by an Alliance with the Colonies as independent States,” as they soon enough would be. In such a case, “she might still enjoy a great Share of the Commerce – that she would have their raw Materials for her Manufactures, that they could protect the West India Islands much more effectually and more easily than she can, that they could assist her in the Newfoundland Trade.” But Howe responded that “it was in vain to think of his receiving, instructions to treat upon that ground.” [43]

And with that, Admiral Howe apologized to the rebel leaders for having put them to “the trouble of coming so far, to so little purpose.” [44] After three hours of conversation, the meeting ended with Howe declaring “that he was sorry to find, that no Accommodation was like to take place,” before he politely escorted the Americans out of the house and to the beach where a barge was waiting to transport them back to Perth Amboy. [45]

***

Ambrose Serle, Admiral Howe’s military secretary, wrote a terse summary of the meeting in his journal: “They met, they talked, they parted. And now, nothing remains but to fight it out against a Set of the most determined Hypocrites & Demagogues, compiled of the Refuse of the Colonies.” [46] The three delegates returned to Philadelphia to report about the meeting to Congress. Adams called it “a bubble, an Ambuscade, a mere insidious Maneuvre, calculated only to decoy and deceive.” [47] Rutledge wrote to General Washington that independence now “relies . . . on your wisdom and fortitude, and that of your forces.” [48]

The conference on Staten Island delayed the British military campaign, providing General Washington with more time to prepare his troops for the inevitable battle for New York City (lower Manhattan). Four days after the “negotiation” the British recaptured New York, forcing the Continental Army’s retreat. The Howe brothers believed the defeat, like the humiliation in Brooklyn, would result in a bid for peace. But the conference on Staten Island exposed the flaw in that logic, since the leadership in Congress was beyond persuasion. It confirmed the irreconcilable differences between the two sides, only stiffening the resolve of each to continue, until the war itself, and the long train of nightmares it produced, forced the British to relent.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Peter Aigner, Director of the Gotham Center for New York City History and Rachel Pitkin, Managing Editor of Gotham: A Blog for Scholars of New York City History for their support and expert editorial guidance. Thanks also to Carol Berkin, Lori Weintrob, and to my colleagues at Union College of Union County, New Jersey (UCNJ) Joseph Margiotta and Michele Rotunda for their careful reading and thoughtful comments.

Phillip Papas received his Ph.D. in History from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He is Senior Professor of History at Union College of Union County, New Jersey (UCNJ), and the author of That Ever Loyal Island: Staten Island and the American Revolution (NYU Press, 2007), Renegade Revolutionary: The Life of General Charles Lee (NYU Press, 2014), and co-author of Port Richmond (Arcadia Publishing, 2009). Papas is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Conference House Association, an organization dedicated to preserving and maintaining the historic Conference House (Billopp House) on Staten Island and to educating the public to its role in the American Revolution. It operates the site in partnership with the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation and the Historic House Trust, and hosts a reenactment of the Staten Island diplomatic peace conference every year in September.

[1] Benjamin Franklin to Admiral Richard Lord Howe, 8 September 1776, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22, www.franklinpapers.org/framedVolumes.jsp, accessed on 15 September 2025.

[2] Admiral Richard Lord Howe to Benjamin Franklin, 10, September 1776, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22, www.franklinpapers.org/framedVolumes.jsp, accessed on 15 September 2025.

[3] Phillip Papas, That Ever Loyal Island: Staten Island and the American Revolution, (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 63, 66-68.

[4] Ernest Schimizzi and Gregory Schimizzi, The Staten Island Peace Conference: September 11, 1776 (Albany, NY: New York State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission, 1976), 5-6.

[5] Barnet Schecter, The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution (New York: Walker & Company), 106.

[6] For the personal and political backgrounds of the Howes see Julie Flavell, The Howe Dynasty: The Untold Story of a Military Family and the Women behind Britain’s Wars for America (New York: Liveright, 2021) and Ira D. Gruber, The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1974).

[7] “Declaration of Vice Admiral Richard Lord Howe, June 20, 1776,” Naval Documents of the American Revolution, https://navydocs.org/node/5384, accessed on 21 September 2025.

[8] Admiral Richard Lord Howe to George Washington, 13 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0212. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 296–297.], accessed on 21 September 2025.

[9] Edward H. Tatum, jr., ed. The American Journal of Ambrose Serle: Secretary to Lord Howe, 1776-1778 (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1940), 31-33.

[10] Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed. Correspondence and Journals of Samuel Blachley Webb. 3 vols. (New York: Lancaster, PA: Wickersham Press, 1893-1894), 1: 155.

[11] “George Washington to John Hancock, 14 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0218. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 304–309.], accessed on 21 September 2025.

[12] “[Wednesday July 17. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0145. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, p. 399.], accessed on 21 September 2025.

[13] Correspondence and Journals of Samuel Blachley Webb, 1: 156. See also Joseph J. Ellis, Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence (New York: Vintage Books, 2014), 95-96.

[14] Ibid, 156.

[15] Ellis, Revolutionary Summer, 96.

[16] “Memorandum of an Interview with Lieutenant Colonel James Paterson, 20 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0295. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 398–403.], accessed on 21 September 2025.

[17] Ibid, accessed on 21 September 2025.

[18] “George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed, 1 April 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0009. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 4, 1 April 1776 – 15 June 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991, pp. 9–13.], accessed on 21 September 2025.

[19] “Memorandum of an Interview with Lieutenant Colonel James Paterson, 20 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0295. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 398–403.], accessed on 21 September 2025.

[20] Papas, That Ever Loyal Island, 77.

[21] Schecter, Battle for New York, 136-139, 147-154 and chap. 10.

[22] “[Tuesday September 3. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0182. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 414–415.], accessed on 3 October 2025.

[23] John Adams to Colonel James Warren, 4 September 1776, quoted in “[Tuesday. September 17th. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0189. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 420–431.], accessed on 3 October 2025. See also Thomas J. McGuire, Stop the Revolution: America in the Summer of Independence and the Conference for Peace (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2011), 130.

[24] See editorial note in “[Tuesday September 3. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0182. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 414–415.], accessed on 3 October 2025. See also McGuire, Stop the Revolution, 130.

[25] Ellis, Revolutionary Summer, 156-157.

[26] “[Thursday September 5. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0184. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, p. 416.], accessed on 10 October 2025.

[27] “[Fryday September 6. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0185. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 416–417.], accessed on 10 October 2025.

[28] Benjamin Franklin to Admiral Richard Lord Howe, 8 September, 1776, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22, www.franklinpapers.org/framedVolumes.jsp, accessed on 15 September 2025.

[29] Ellis, Revolutionary Summer, 158.

[30] “[Monday September 9, 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0187. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 417–420.], accessed on 25 October 2025.

[31] Flavell, Howe Dynasty, chap. 6.

[32] “[Monday September 9, 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0187. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 417–420.], accessed on 25 October 2025.

[33] Ibid, accessed 25 October 2025.

[34] Ibid, accessed 25 October 2025.

[35] “Lord Howe’s Conference with the Committee of Congress, 11 September 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0358. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22, March 23, 1775, through October 27, 1776, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982, pp. 598–605.], accessed on 31 October 2025.

[36] “[Tuesday. September 17th. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0189. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 420–431.], accessed on 12 November 2025.

[37] “Lord Howe’s Conference with the Committee of Congress, 11 September 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0358. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22, March 23, 1775, through October 27, 1776, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982, pp. 598–605.], accessed on 12 November 2025.

[38] “[Tuesday. September 17th. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0189. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 420–431.], accessed on 12 November 2025.

[39] “Lord Howe’s Conference with the Committee of Congress, 11 September 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0358. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22, March 23, 1775, through October 27, 1776, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982, pp. 598–605.], accessed on 12 November 2025.

[40] Ibid, accessed on 12 November 2025.

[41] “[Tuesday. September 17th. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0189. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 420–431.], accessed on 12 November 2025.

[42] “[Tuesday. September 17th. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0189. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 420–431.], accessed on 12 November 2025. See also McGuire, Stop the Revolution, 164.

[43] “Lord Howe’s Conference with the Committee of Congress, 11 September 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0358. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22, March 23, 1775, through October 27, 1776, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982, pp. 598–605.], accessed on 16 November 2025.

[44] Ibid, accessed on 16 November 2025.

[45] “[Tuesday. September 17th. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0189. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 420–431.], accessed on 20 November 2025.

[46] American Journal of Ambrose Serle. 101.

[47] John Adams to Samuel Adams, 14 September 1776 in “[Tuesday. September 17th. 1776.],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0189. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 420–431.], accessed on 20 November 2025.

[48] “Edward Rutledge to George Washington, 11 September 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0228. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 6, 13 August 1776 – 20 October 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase and Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994, pp. 286–287.], accessed on 20 November 2025.