Schlep in the City: Walking Broadway

By Katie Uva

Watercolor sheet music, ca. 1920. Museum of the City of New York.

New York City can be overwhelming in its vastness — more than 300 square miles, more than 8.5 million people, and so many distinct neighborhoods and languages spoken here that the number of neighborhoods and languages aren’t even fully agreed upon. New York City’s streets are the nervous system binding this far flung place and giant population together and their idiosyncrasies seem fitting for this metropolis — Edgar Street and Mill Lane in Manhattan vie for shortest street, while my childhood in Queens was punctuated by persistent confusion about whether I lived on 68th Road, Drive, or Avenue. Each borough has a Main Street, and Waverly Place has the distinction of being the only street in New York that actually crosses itself.

The Harlem River as seen from the Broadway Bridge.

One of the most striking features of many New York streets, however, is more intangible than length or shape. So many of these streets are metonyms, embodying a bigger concept than the physical space they denote. Wall Street: the world of American finance. Madison Avenue: mid-century advertising. And perhaps the most legendary of all: Broadway. For most people the name conjures the theater industry that occupies its center, full of bright lights, marquees, and creative ambition. This is a core component of Broadway, yet this street has so much more to it — it’s the longest street in Manhattan and stretches the entire length, cutting assertively across the grid with the force of a longer history behind it and leaving a trail of small parks and squares in its wake. On a beautiful spring day, some friends and I set out to walk the length of Broadway in Manhattan from top to bottom, a journey totaling 13.5 miles. In addition to 27 Starbucks and 18 McDonalds, here are some other highlights of what we saw:

We began our journey in Marble Hill. Although on a map it appears to be unequivocally part of the Bronx, Marble Hill is administratively part of Manhattan, which makes it the northernmost neighborhood and Manhattan and the neighborhood in Manhattan whose residents have to travel the farthest for jury duty. Exiting the 1 station at 225th street, we crossed over the Broadway Bridge on foot, affording us a view of the Harlem River.

Arriving back in Inwood, we found ourselves flanked by two signs of a lower-density part of the city — large, heavily forested parks on our right, and a series of utilities, storage depots, and bus terminals on our left. We were struck by the dramatic topography of this part of Manhattan — the parks rise up on steeply forested hills veined with staircases and there are several apartment buildings atop stark cliffs. While recent linguistic scholarship questions the conventional translation of Manhattan, it is certainly evident walking around its upper portions that this is indeed a place of many hills.

At 204th and Broadway we stopped and pondered the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum, sitting handsomely atop one of those hills. Built in 1784, it is the oldest farmhouse in Manhattan, which is both an impressive feat and also demonstrates the vagaries of Manhattan real estate. The other four boroughs all have farmhouses from the 18th century, but houses from the same period in Manhattan were regularly lost to fires, destroyed in the Revolutionary War (as is the case for the house that occupied this spot before the current Dyckman house), sold, resold, and demolished to make way for more commercially viable properties. The Dyckman Farmhouse itself nearly met the same fate before being repurchased by Dyckman descendants in 1915 and then turned into a museum from 1916-onward.

View of the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum from Broadway.

United Palace Theater.

We proceeded steadily down Broadway and were struck at 176th street by the grandeur of the United Palace Theater. Built in 1930 by Thomas W. Lamb, one of the leading theater designers of his day, its exterior is a jaunty collection of terracotta crenellations and fluted pilasters, an eclectic mix of styles described by the Landmarks Preservation Commission as "Indo-Persian," and by the AIA Guide to New York City as "Cambodian neo-classical." Forty-six years after it was first proposed, in 2016 the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated this theater, one of five Loew's "Wonder Theaters" in the New York metropolitan area, a landmark.

At Broadway and La Salle Street, just below 125th, we considered the vast amount of neighborhood change and contestation of space that has taken place in this particular area over the years. The western side of the street is a collection of six-story walkups dating from the early 20th century, while the view east shows two late 1950s housing projects — Grant Houses, on the north side of La Salle Street, and Morningside Gardens, on the south side. These complexes were the culmination of what the New York Times described in 1957 as "a mammoth face-lifting." A group of leaders from the educational institutions south of the site, including the presidents of Barnard and Columbia, pushed for the demolition of existing tenements in favor of the building of a new complex that would provide integrated co-op apartments for middle-class residents. The Board of Estimate approved this plan, paired with the construction of public housing across the street. A group of residents, fearing displacement and the destruction of their neighborhood, formed an organization called Save Our Homes, but they were defeated by a well-funded and powerful coalition who favored the buildings and accused Save Our Homes of harboring communists. [1]

Morningside Gardens and Grant Houses provide an opportunity to consider the ambitions, the shortcomings, and contradictions of urban renewal. They were created with the strong partnership of the federal government; Title I funds backed the construction of Morningside Gardens and federal funds kept and continue to keep Grant Houses rents below market rates. Their supporters saw them as an opportunity to clear old, blighted slums and engineer a diverse community; however, in the process of doing that they overrode the objections of a diverse group of existing residents who already loved their community and displaced about 3,000 people. That being said the buildings now do stand as bastions of affordability in an area that has seen massive increases in housing costs over the past twenty years, increases that have been partly exacerbated by Columbia's controversial expansion above 125th street.

The view from the west side of Broadway: Morningside Gardens on the right, Grant Houses on the left.

The Ansonia.

As we made our way down the Upper West Side, we began talking animatedly about the hot dogs we were going to get at Gray's Papaya (a mission we soon accomplished). But we also noted the mass and grandiosity of the apartment buildings we passed. Turrets, limestone, mansard roofs, and cupolas abounded. Among its stately sisters I was particularly taken with the Belleclaire, which exudes a feeling of tenacity. Its ground floor is currently bound by scaffolding and its exterior — red brick with limestone trim — seems downright scrappy compared to the Ansonia or the Apthorp. This is a building that has seen a lot of ups and downs over its 115-year history.

The Belleclaire was one of Emery Roth's first projects in New York, a precursor to his legendary apartment buildings on Central Park West. Completed in 1903, it was one example of a first generation of opulent structures designed to entice upper-class New Yorkers into apartment living. The building was landmarked in 1987, and its designation reportcharacterizes its mixture of Art Nouveau and Secessionist architecture styles as "a fascinating stylistic anomaly." Its original bowling alley in the basement is gone, as is the cupola that once topped its northeastern turret. But its lively and dynamic facade remains, and after years as an SRO stripped of many of its original features, it has now been reconfigured as a hotel with restored details.

The Belleclaire.

Like the New Yorkers we are, we started to get cranky as we approached midtown. From 59th to 34th streets, we kept our heads down, swerved around tourists, and dodged pitches from various costumed Elmos and Doras the Explorer.

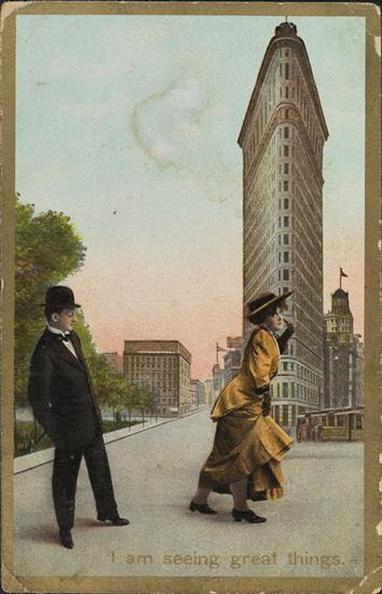

At 23rd and Broadway the Flatiron Building greeted us, jutting proudly into the intersection, as many before me have noted, like the prow of a ship. When it started rising from its astoundingly irregular footprint in 1902, it delighted some and disgusted others. An unexpected side effect of its size and placement was its tendency to create wind tunnels, to scandalous effect.

As we approached the end of our journey, we encountered two buildings that nicely highlight New York City's journey through zoning regulation. The Equitable Building, at 120 Broadway, was the largest office building in the world when it was completed in 1915. But soon after it opened complaints mounted from its neighbors about the massive shadows cast by its unbroken, 40-story facade. These concerns added greater urgency to a debate that was already occurring about what the unchecked growth of skyscrapers might mean for New York's future. In 1916 New York passed its first zoning regulation, limiting the mass of buildings once they reached certain height thresholds. Architects adapted to this regulation with the use of setbacks, giving a generation of New York's skyscrapers their distinct silhouettes.

In 1961 the zoning law was amended — among the new standards was a concept called incentive zoning, which meant that buildings could be tall with flat facades if they were set back from the street and provided a public plaza. 140 Broadway, built in 1968, is a prime example of this principle in action. It features a quintessential 1960s paved plaza whimsically offset by Isamu Noguchi's Red Cube.

Sun shines on the shadow-casting Equitable Building.

140 Broadway with its 1961 Zoning Law-enabled plaza and public art by Isamu Noguchi.

Six and a half hours and 13.5 miles after we started, we arrived, proud and footsore, at 1 Broadway. We high-fived, took a moment to enjoy the easy legibility of the address we stood in front of, and got in line at the ice cream truck outside the building. Ice cream in hand, with New York Harbor sparkling to our right, we gazed at one last site — the U.S. Customs House. Now home to the National Museum of the American Indian, it stands largely in the footprint of the first major structure recorded here — Fort Amsterdam. How poignant and disorienting New York can be — we traversed an entire island's worth of architectural innovation, economic rises and falls, deep and unresolved arguments about gentrification and neighborhood character, cliffs and forests, hot dogs and ice cream, to find ourselves contemplating a museum striving to interpret the lives of people whose own displacement and quest for survival was set into motion by the settlers who previously built a fort in the same spot. And our own vantage point at 1 Broadway is built on landfill, and originally would have been in the river — the invented coast of an infinite city.

Katie Uva is the Coordinating Editor of Gotham.

Notes

[1] For more on Morningside Gardens, see Themis Chronopoulos, Spatial Regulation in New York City: From Urban Renewal to Zero Tolerance; Andrew Dolkart, Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development;and Samuel Zipp, Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Postwar New York.