The Scenography of Power at Bowling Green

By Paul A. Ranogajec

Bowling Green, a surviving fragment of New York’s earliest days, was totally transformed in the decades around 1900. What had been a low-scale square of houses and small offices became a skyscraper-ringed urban canyon, a spectacle of corporate and state power. That spectacle resulted from a scenographic approach to architecture in which designers orchestrated buildings and spaces together as an ensemble for dramatic visual and experiential effects. Architects who worked at Bowling Green were committed to the traditional urban streetscape, but their designs also gave form to the imperatives and values of the emerging corporate-capitalist economy. That meant skyscrapers. At Bowling Green, skyscrapers and the new Custom House together reshaped the historic square, providing visible, material proof of the intensity and speed of the economy’s corporate transformation.

Bowling Green and vicinity in 1911. New York Public Library.

Olivier Zunz argues that the first generations of skyscrapers did not just represent corporate culture but were bound up with larger processes of social construction in the modern American city.[1] They helped shape new experiences of work and urban space. Skyscrapers participated in the process that Martin Sklar calls the “corporate reconstruction of American capitalism,” which reconfigured Americans’ understanding and lived experience of the economy, property, politics, and society from the 1890s through the 1910s.[2] As a constituent part of the complex of social relations, architecture tangibly brought these changes into the daily life of the city. They were materialized in the intimate, direct experience—which carried psychological and phenomenological significance—not only of everyone who worked in the new skyscrapers, but of all the city’s residents and visitors. If skyscrapers were the “vernacular of capitalism,”[3] in New York these buildings necessarily took on some of the civic functions that more traditional building types had served earlier. The transformation of Bowling Green exemplifies these processes at work in the city.

* * *

Spencer Trask, a prominent financier and philanthropist, began his 1898 essay on the history of Bowling Green by placing it in the context of extraordinary material changes sweeping across the city at the time. He wrote,

Absorbed in the whirl and stir of the To-day, occupied with vast schemes and enterprises for the To-morrow, overswept by a constant influx of new life and new elements, it [New York] seems to have no individual identity. It does not hold fast its old traditions, its past associations….

[But] there is no piece of land on Manhattan Island which has retained for a longer period its distinctive name, and at the same time fulfilled more thoroughly the purposes of its creation, than the small park at the extreme southern end of Broadway, known as Bowling Green. It is the one historic spot which has never lost its identity or been from public use since the foundation of the city.[4]

Closely linked to the Battery and the harbor, the square has long been a vital point in the city’s spatial-geographical structure and civic landscape.

“The Plaine,” later the “bowling-green,” was the largest common space in Dutch New Amsterdam, formed in the 17th century as a clearing next to the city’s fort (which determined the twisted triangular shape of the square’s plan). After the fort’s removal in 1789, Government House was built there -— “plac’d upon an handsome elevation”[5] -— as the president’s residence at the moment when New York was being considered for the national capital.

The square was then directly adjacent to the waterfront, and as a gateway into the city it must have seemed a fitting place for the new nation’s most representative state building. However, the Residence Act of July 1790 relocated the national capital far away on the banks of the Potomac River. Government House then served briefly as the state governor’s residence and subsequently the Custom House; it was destroyed by fire in 1815. But the square remained significant as both the “green hearthstone of welcome” to the ever-growing and bustling commercial port and a place associated with nationhood (George Washington even had a residence there). From the beginning, then, geography and architecture together produced a space of economic and political power.

* * *

Bowling Green’s transformation began in 1880 when the Produce Exchange announced it would move to the southeast corner of Beaver and Whitehall Streets. With land and construction -- and a huge footprint of 53,779 square feet -- the Produce Exchange cost over $3 million, upending property values in the immediate area. As the near decade-long economic depression lifted at the end of the 1870s, large-scale investments in building and speculative development ushered in a new era of change at Bowling Green and elsewhere.[6] Soon, the tall Washington Building (Edward Kendall, 1882) also opened there, at the corner of Battery Park. These two early interlopers at the square forecast the scale and functions of the new architecture to come over the next four decades.

Produce Exchange. Photograph c. 1904. Library of Congress.

Bowling Green. Washington Building at left. Photograph 1900. Library of Congress.

The Welles Building (W. Pell Anderson, 1883) at the square’s northeast end on Broadway introduced two design elements that would become defining architectural motifs around the square: the tripartite facade—three vertical sections, of which the central one was set back from the flanking sides, or pavilions—and classical rustication, the visual emphasis on stone joints and masonry textures. Although the tripartite composition was new, other elements were typical of nine and ten story office buildings of the 1880s -- for instance, the repetition of decorative details on each floor and the dominant horizontal divisions.[7]

Welles Building (right). Photograph 1886. New York Public Library.

After a lull of several years, the Bowling Green Offices (William and George Audsley, 1895-98) -- a building “quite too conspicuous to be ignored” -- went up.[8] Its prominent Greek capitals, decorative moldings, and deep-set windows lend the building a solid, almost rock-cut effect. The Audsley’s composed their building using the tripartite scheme of the Welles Building. Although eschewing the Welles’ Renaissance rustication for bolder ornament, the massing and compositional format initiated by the Welles was confirmed as the square’s distinct architectural modality, quickly putting the stout and florid Washington Building out of fashion. As it slowly emerged around the square, the tripartite design had the effect of individualizing each building while maintaining the solidity and continuity of the street wall. It was “traditional” even while it utterly transformed the square.

Bowling Green Offices. Photograph 1900. New York Public Library.

The United States Custom House was the next addition to the square. One of the city’s most important civic buildings from the years immediately after the municipal consolidation in 1898, the Custom House anchored Bowling Green with a structure of national importance, reinforcing the character of the square as gateway to the nation’s metropolis. Custom houses and mints had been among the most prominent symbols of the “federal presence” in American cities since the middle of the nineteenth century.[9] New York’s latest had a three-fold representational purpose: it was an institutional instrument of the federal government’s centralized authority over international commerce and the modern industrial economy; it was a critical tool in international shipping and Transatlantic voyages, now dominated by large corporations; and it was a public building fronting one of the most important squares in the metropolis. Planned at a time of breakneck rebuilding in the city, it brought high expectations regarding its character and contribution to the cityscape.

United States Custom House. Photograph 1908. New York Public Library.

Champions of the Bowling Green location for the Custom House argued that it afforded the “possibility of architectural display” and was at “almost the geographical centre, north and south, of the greater City of New York.”[10] Cass Gilbert, the building’s architect, declared his intent “to make the building in every way a fine thing, and worthy of its place and of its object in the large sense.”[11] The design had to manage three different approaches with distinctive urban vistas: from the north along the turning course of Broadway and Whitehall Street, from the south along Whitehall, and from Battery Park and the harbor to the west.

Gilbert’s Custom House design, with its thick circuit of masonry walls and heavy rustication, further developed the continuous wall of stone around Bowling Green. The use of the classical orders also had an urbanistic function. While the side colonnades recede into the blocky mass of the building, forming lines of columns that dramatize the oblique vistas down Whitehall Street and from within Battery Park and the harbor, the front colonnade projects forward, dramatizing the terminating vista from Broadway. According to Gilbert, the front facade with its colonnade and sculptural embellishments was designed to be “so impressive by reason of the majesty of its composition, rather than by its actual size, that it should be truly a monument.”[12]

View toward Custom House from Broadway. Photograph c. 1910. Library of Congress.

The building’s massiveness and solidity, its stony embrace of the passerby at ground level, impart a strong feeling of enclosure and attachment to the square. Its Bowling Green front enhanced the square’s emerging urbanistic modality: an embracing stone enclosure offering varied vistas from multiple points of view. To borrow words from Michel de Certeau (describing a different New York context), in this urban modality the citizen’s body is “clasped by the streets that turn and return it.”[13] While the square’s new skyscrapers adeptly enclosed the space and clasped the visitor’s body, the Custom House’s “broad shapes of stone” were designed to convince passersby that they were in “the presence of a great Temple of Commerce, the meeting place of all the nations to do business with the New World.”[14] Charles de Kay captured this effect, writing that “as you descend Broadway and turn the bend … there is a slightly elevated view of the edifice, and fortunately not the least favorable. The powerful basement and mighty columns bear up well the weight of the superincumbent mass, and seem to perform their function instead of being merely the decorations of a wall.” Recalling the history of the site, de Kay speculated that “perhaps these robust walls will suggest a fort” to some future archaeologists, “and the new locality may well cause a confounding of the new Custom-house with the old fort.”[15]

View of Manhattan in 1874. New York Public Library.

View into Bowling Green from the opening to Battery Park. Photograph c. 1899. New York Public Library.

The building up of Bowling Green had the effect of emphasizing the space as a channel into Manhattan when seen from Battery Park and the harbor -- an effect already suggested by the square’s very configuration and position. The new buildings around Bowling Green seemed to direct the flow of space into the spine of Broadway, visually linking the square with the rest of the city and reinforcing its geographical centrality. The Custom House added to this effect by its low profile, allowing views into the space from the water and park, and by making the square into its forecourt. There was once again, like Government House a century earlier, an institution of the state at the head of the square -- low in height but commanding in presence.

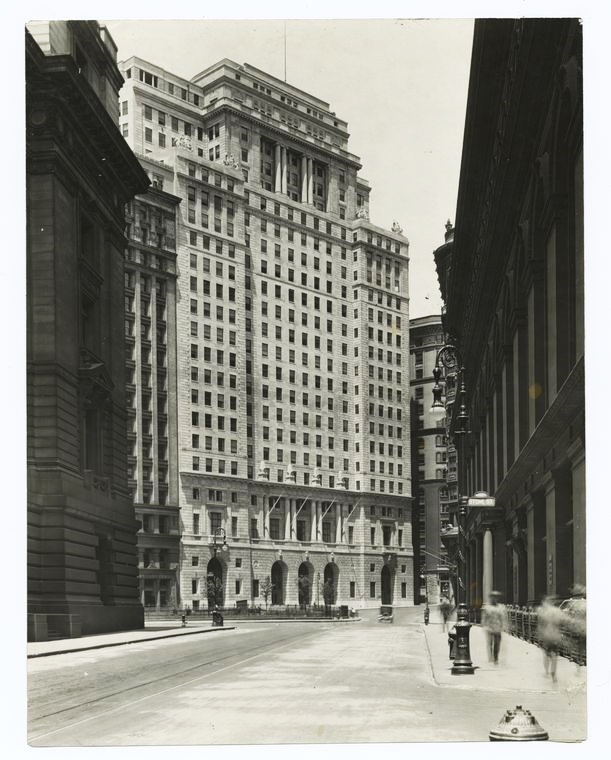

View of the Cunard Building from Whitehall Street. Photograph c. 1922. New York Public Library.

Two final buildings, designed and built after World War I, augmented and completed the scenography of Bowling Green: the Cunard Building (Benjamin Wistar Morris, 1918-21) and Standard Oil Building (Carrère and Hastings, 1920-28) astride Broadway at the northern edges of the square. Together these two large buildings completed the continuous street wall modality of Bowling Green. They increased the length of the stony embrace around the space, and they completed the corporate reconstruction of the square.

The two buildings resulted from changes in the real estate market and the fortunes of corporate business in the years immediately following World War I. According to a report in the Times, the rebuilding promised to “create a whole new city below Wall Street.”[16] “Creative destruction,” that ever-present accompaniment to capitalist development in New York, was working its machinery to transform whole districts throughout the city.[17] The building up and densifying of lower Manhattan, which turned it into a corporate cityscape of large office buildings to the exclusion of almost everything else, was a dramatic rendering of this process.

Hugh Ferriss. The Cunard Building. From The Century, September 1921.

The Bowling Green Offices next door suggested the general treatment of the Cunard’s tripartite massing. But Morris’ design is articulated by large-scale elements while the Bowling Green Offices has deep window reveals that cut up the facade into a cell-like grid pattern. The Cunard’s windows, set close to the face of the wall and unornamented, create a “towering mass of plain wall surface” that gives a sheer vertical effect.[18] As art critic Royal Cortissoz described it, “There are no teasing details to disturb the calm of these noble walls. The arched base, like the pillared stage it carries, is refined very nearly to the point of austerity. As the facade soars to its height there are no decorative littlenesses to mar the broad and powerful sweep of the design.” The composition—unified, streamlined, and massive—imparts a “living quality.” “Gone,” says Cortissoz, “is the deadness, the inertia, the banality, of the skyscraper…. Gone is the empty gesture of adventitious ornament…. The facade holds you by its beauty and at the same time it persuades you that it is the outward, visible sign of an inward interest, a good plan.”[19]

“Holds you by its beauty” is the key phrase. Like the Custom House’s stony embrace of thevisitor, the Cunard makes the viewer acutely aware of their own presence in the square. Cortissoz wrote, “All manner of far-reaching implications suggest themselves in the grandiose nature of the facade.” Among these is the importance of the viewer’s perspective on the building from vantage points around Bowling Green. “For once,” Cortissoz observed, “a skyscraper may be seen in something like perspective.”[20]

Standard Oil Building. Photograph c. 1928. New York Public Library.

The ability of the building to “hold” the viewer is most clear in early views of the Cunard from Whitehall Street. It is a captivating sight, framed by the large-scale columns and arches of the Custom House to the left and the Produce Exchange to the right. Hugh Ferriss’s small sketch emphasizes the building’s sheer mass, representing it as a stony cliff pierced by colonnades and arcades at the top and bottom, creating a play of light and shadow. The building terminates the Whitehall Street vista but also presents itself almost in the guise of a seat, perhaps even an urban throne, on which the viewer can imagine sitting and becoming immersed in the bodily experience of the square’s powerful scenography. In this way, it “holds the viewer.”

View of Bowling Green from the Custom House. Cunard Building at left, Standard Oil Building at right. Photograph c. 1935. New York Public Library

The Standard Oil Building’s architect, Thomas Hastings, held an ambivalent attitude to the skyscraper that was typical of his fellow architects. He recognized that the “originality and modernity of these monstrous palaces of industry” had transformed city streets “into canyons of human habitation.”[21] But he contributed to the canyon effect with his tall buildings, especially the Standard Oil, evidence of both the conflicted attitude of architects and the economic realities of professional work. Buildings such as the Standard Oil and Cunard, although tall, deemphasized height as the primary expressive value in an effort to temper the scale-less effects of skyscraper development and provide an alternative way of constructing coherent urban space. At Bowling Green, concern for height only came after concern for street-level scenography.

Hastings incorporated into Standard Oil’s design a number of elements that were basic building blocks at the Cunard: the podium as a rusticated base with arcade; the seat- or throne-like, tripartite composition; and the upper colonnades. Early views of the Standard Oil Building—built on the site of the earlier Welles—captured the way in which it locks into the formal architectural conditions of the site: elevated above the square, taken from the steps of the Custom House or from the opening to Battery Park. From those particular viewpoints, the Standard Oil Building seamlessly joins with its surroundings, making it seem a natural completion of the scenographic effects already established at the square. By contributing to the formal reciprocity of the square’s architectural language, especially in close relation to the Cunard Building, the Standard Oil was a conspicuous example of the way in which New York’s architects, with larger public aims in mind, imposed a civic code on private buildings. It also consummated Bowling Green’s transformation into a space of corporate and state power.

* * *

With the Standard Oil Building, the architectural ensemble at Bowling Green was complete. Tall buildings now enclosed the square and clasped the visitor’s body, and the Custom House’s “broad shapes of stone” anchored the whole. The orchestration of scenographic effects around Bowling Green emphasized the square’s role as the entrance to the city and its historical origin point. They also made the space an urban spectacle of the comingling and mutuality of corporate capitalism and government authority. Bowling Green had become a showplace par excellence for the architecture of power. It had also become a public space surrounded by impressive architecture. The contradictions are deep and unresolvable, and integral to the perceptions and meanings of the square through the ages—and never more starkly than during the age of corporate consolidation around 1900. But the mediating power of great architecture and urban experience means that the significance of a place can never be reduced to one set of meanings. Bowling Green is a square of unique architectural power, in many senses of the word.

Paul A. Ranogajec is an architectural and art historian. He recently earned a Ph.D. from The Graduate Center, CUNY.

[1] Olivier Zunz, Making America Corporate, 1870-1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 8.

[2] Martin J. Sklar, The Corporate Reconstruction of American Capitalism, 1890-1916: The Market, the Law, and Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

[3] The phrase is from Carol Willis, Form Follows Finance: Skyscrapers and Skylines in New York and Chicago (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1995).

[4] Spencer Trask, “Bowling Green,” in Historic New York: Being the Second Series of the Half Moon Papers, ed. Maud Wilder Goodwin, et al. (New York: Putnam’s, 1899), 165-66.

[5] John Drayton (1793) quoted in ibid., 198.

[6] On these changes, see David M. Scobey, Empire City: The Making and Meaning of the New York City Landscape (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002).

[7] See Barr Ferree, “The High Building and Its Art,” Scribner’s Magazine, Mar. 1894, 311.

[8] “The Bowling Green Building,” Real Estate Record and Builders Guide, May 15, 1897, 826.

[9] See Lois A. Craig, The Federal Presence: Architecture, Politics, and Symbols in United States Government Building (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1978); and Robert A. M. Stern, et al., New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism 1890-1915 (New York: Rizzoli, 1995), 74.

[10] “Petition Concerning Site of Proposed New Custom House,” in Report of the New York Produce Exchange from July 1, 1896, to July 1, 1897 (New York: Jones Printing Company, 1897), 44-6.

[11] Cass Gilbert, quoted in “Custom House Architect,” New York Times, Nov. 4, 1899.

[12] Gilbert, quoted in “Cass Gilbert’s New York Customhouse Design,” Inland Architect and News Record, Feb. 1900, 6.

[13] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendell (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 92.

[14] “World’s Greatest Custom House Will Soon Be Completed,” New York Times, Jan. 14, 1906.

[15] Charles de Kay, “The New York Custom-House,” Century Magazine, Mar. 1906, 735

[16] “Many Lower Manhattan Landmarks Doomed When Building Era Begins,” New York Times, Nov. 23, 1919.

[17] For this process at work, see Max Page, The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900-1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

[18] Benjamin Wistar Morris, quoted in “The Cunard Building, New York,” Architecture and Building, Aug. 1921, 62.

[19] Royal Cortissoz, “The Cunard Building: A Great Achievement in New York, by Benjamin Wistar Morris,” Architectural Forum, July 1921, 4.

[20] Ibid., 8, 1.

[21] Thomas Hastings, “The New York Sky Line,” in Thomas Hastings, Architect: Collected Writings, Together with a Memoir, ed. David Gray (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1933), 222.