The Earliest Sculptures in Central Park

By Dianne Durante

The only sculpture originally slated for the Park

In Olmsted and Vaux’s Greensward Plan, the only sculpture was one atop the fountain at the center of Bethesda Terrace. The commission for the sculpture was given in 1863 to Emma Stebbins (1815-1882), an American-born sculptor working in Rome who happened to be the sister of a member of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park.

Stebbins’s eight-foot-tall fountain figure is an allegory for the life-saving, clean water of the Croton Aqueduct. According to Scripture (John 5:2-4), at Bethesda, near Jerusalem, an angel occasionally came down to stir the waters of a certain pool. The first person to step into the pool afterwards was cured of anything that ailed him. The main figure of Bethesda Fountain is the Angel of the Waters, about to stir. The four-foot-tall putti below her represent Purity, Health, Temperance, and Peace.

Left: Sketch for Bethesda Fountain in the Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park for 1864. Center and right: Emma Stebbins, Bethesda Fountain, dedicated 1873. Photos copyright © 2017 Dianne L. Durante

Stebbins sent the sculptures to be cast in 1867, but due to the Franco-Prussian War and a delay in completing the monumental stone basin in Central Park, the fountain was not dedicated until 1873.

The day after the dedication, the New York Times published scathing comments on the Angel of the Waters. After describing a lovely spring day in the Park, with children frolicking and a band playing, the Times reported:

When the authorities, without any speech-making or declamation, withdrew the cloakings that shadowed the expected form of art, there was a positive thrill of disappointment. All had expected something great, something of angelic power and beauty, and when a feebly-pretty idealess thing of bronze was revealed, the revulsion of feeling was painful. --New York Times, 6/1/1873

But familiarity often breeds fondness: it’s difficult to imagine anything else topping the fountain at Bethesda Terrace.

*****

Aside from animals—live, stuffed, fossilized (see Chapter 6.4 and 6.6)—people also donated art to Central Park. Much of it was stored in the Arsenal, but while Bethesda Fountain was in progress, a number of other sculptures were set outdoors in the Park.

Left: C.L. Richter, Schiller, dedicated 1859, shown in the Ramble during the 1860s or 1870s. Image: New York Public Library Digital Collections. Center: Christophe Fratin, Eagles and Prey, 1850, dedicated 1863. Just west of the Mall. Photo copyright © 2017 Dianne L. Durante. Right: Auguste Cain, Tigress with Cubs, 1866. Central Park Zoo. Photo copyright © 2017 Dianne L. Durante

Schiller, dedicated 1859, by C.L. Richter

The earliest sculpture to be displayed outdoors in the Park was a bronze bust of Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805), German playwright and poet. Beethoven based the final movement of the Ninth Symphony on Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”. Donizetti, Rossini, and Verdi all composed operas inspired by Schiller’s plays.

Olmsted stashed Schiller in the Ramble, to keep him from disrupting the pastoral vibe elsewhere. The bust now stands on the Mall, near Beethoven and opposite the Naumburg Bandshell.

Eagles and Prey, dedicated 1863, by Christophe Fratin

Cast in 1850, Eagles and Prey is the oldest sculpture in the Park—unless you consider the Obelisk a sculpture. (Schiller was cast later than Eagles, but dedicated earlier.)

Christophe Fratin was a member of the “animalier” school that flourished during the mid-nineteenth century. The animaliers specialized in the naturalistic representation of animals with a romantic slant: animals displaying emotions that humans could relate to. This sculpture of eagles ripping apart a goat probably had a more immediate association for the Board of Commissioners. When construction of the Park began, the numerous goats wandering free in Manhattan treated the tender new plants as a buffet. At Olmsted’s suggestion, the Board offered a dollar (about half a day’s wages) to anyone who brought a goat to the pound.

Tigress with Cubs, 1866, by Auguste Cain

This example of animalier sculpture—a tigress bringing a dead peacock to feed her cubs—is also an insider’s joke. It was originally placed on Cherry Hill, just west of Bethesda Terrace, where live peacocks roamed.

Clarence Cook’s 1869 guidebook to Central Park condemned both Eagles and Tigress as inappropriate to the Park:

They are, both of them, fine and spirited works of their kind, but they are much better suited to a zoological garden than to a place like the Park, for the ideas they inspire do not belong to the tranquil, rural beauty of the Park scenery. ... They are simply records of carnage and rapine, and however masterly the execution, or however profound the scientific observation they display, they are apart from the purpose of noble art, whose aim is to lift the spirit of man to a higher region and feed him with grander thoughts. --A Description of the New York Central Park, p. 73

Left: John Quincy Adams Ward, Indian Hunter, dedicated 1869. Center: John Quincy Adams Ward, Seventh Regiment Memorial, dedicated 1869. Right: Gustaf Blaeser, Alexander von Humboldt, dedicated 1869. Photos copyright © 2017 Dianne L. Durante

Indian Hunter, dedicated 1869, by John Quincy Adams Ward

Indian Hunter was the breakthrough work for John Quincy Adams Ward, who became one of America’s leading sculptors.

By the 1860s few New Yorkers had ever seen an Indian: the frontier was two thousand miles to the west. The small model of this sculpture that Ward exhibited in 1865 (now at the Metropolitan Museum) had decidedly Caucasian features. After August Belmont, Richard Morris Hunt, and others commissioned Ward to create a life-size version of Indian Hunter for the Park, Ward traveled to the Dakota Territory to study Indians, so that he could render the facial bone structure more accurately.

Seventh Regiment Memorial, dedicated 1869, by John Quincy Adams Ward

In 1867, the Seventh Regiment—also known as the “Silk Stocking Brigade,” because it was composed of wealthy New Yorkers—requested permission to erect a memorial to its fifty-eight members who had died during the Civil War. Although Ward created a figure that looks ordinary, this memorial was the first of its kind: it represented not a military leader but a citizen-soldier. Towns across the United States commissioned mass-produced variations of the Seventh Regiment Memorial.

Humboldt, dedicated 1869, by Gustaf Blaeser

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was one of those rare men equally fascinated by the trees and the forest. He collected masses of quantitative data, but also wrote the five-volume Cosmos, an attempt to integrate all man’s knowledge. Cosmos was one of the most widely read science books ever written, and may have influenced the decorative scheme for Bethesda Terrace. This bust was originally at the Scholar’s Gate (Fifth Avenue at Central Park South). It was later moved to face the American Museum of Natural History.

First: Byron M. Pickett, Samuel F.B. Morse, dedicated 1871. Second: Sir John Steell, Sir Walter Scott, dedicated 1871. Third: John Quincy Adams Ward, Shakespeare, dedicated 1872. Fourth: George Blackall Simonds, Falconer, dedicated 1875. Photos copyright © 2017 Dianne L. Durante

Morse, dedicated 1871, by Byron M. Pickett

In the 1830s, Samuel Finley Breese Morse (1791-1872), a portrait painter and professor at New York University, cobbled together a battery and a single transmission wire and developed what we know as “Morse code”. Morse’s telegraph made him a wealthy man—and gave the world, for the first time, long-distance communication that was cheap and almost instantaneous. Near-instantaneous transmission of financial data and transactions made regional stock markets in Philadelphia and Boston obsolete. Hence New York’s Wall Street became the nation’s financial capital (see Chapter 2.2.4). Morse was a hero worldwide, but especially in New York City. In June 1871, eighty-year-old Morse became the last man ever to attend the dedication of his own portrait sculpture in Central Park.

Scott, dedicated 1871, by Sir John Steell

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) declined an invitation to be poet laureate of Great Britain in order to create (anonymously) a new genre: the historical novel. From Waverly to the Bride of Lammermoor, from Ivanhoe to Rob Roy,Scott’s works were enduring bestsellers. On the centennial of Scott’s birth, New Yorkers dedicated a sculpture to him in Central Park.

Shakespeare, dedicated 1872, by John Quincy Adams Ward

During the mid-nineteenth century, the works of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) were being read by fur traders in Wyoming and miners rushing to the California gold fields. In 1864, although the nation was in the throes of civil war, many New Yorkers were eager to commemorate the three-hundredth anniversary of William Shakespeare’s birth. The cornerstone for a figure of Shakespeare in Central Park was laid that year.

To raise money for the sculpture, Edwin Booth and his brothers Junius Booth and John Wilkes Booth (the future presidential assassin) appeared on stage together for the first and only time, in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. The statue was finally dedicated in 1872.

Falconer, dedicated 1875, by George Blackall Simonds

New Yorker George Kemp made a fortune selling “Florida Water,” advertised for use as toilette water, aftershave, and relief for insect bites and/or frayed nerves. You can still buy it today. On a trip to Europe, Kemp fell in love with this sculpture of a young aristocrat flying a falcon, and offered to pay for a copy to stand in Central Park. Falconer was set high on a rock overlooking the Lake. The New York Times complained that it “should most certainly have been placed at least 15 feet lower than it is,” but also commended the Falconer as “one of the few really artistic statues that have been placed in Central Park.”

The Board of Commissioners’ Rules on Sculpture, 1873

By 1873, when Angel of the Waters was dedicated, so many sculptures were being donated to the Park that the Board of Commissioners decided to set rules for sculptures placed there. (See their annual report for 1872-1873, published in 1875.)

The Board had to see either a complete sculpture or a finished model before it would authorize placement in the Park.

The sculpture had to be approved by the presidents of the National Academy of Design, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the American Institute of Architects.

On the Mall, only sculptures commemorating men and events of “far-reaching and permanent interest” could be erected.

Near each gate, portraits or commemorative sculptures appropriate to that gate could be erected. For example, a sculpture of a woman might be placed near the Women’s Gate, or a sculpture of a soldier near the Warriors’ Gate.

No portrait sculpture could be erected until at least five years after its subject had died. That’s why Morse was the last person to attend the dedication of his own portrait sculpture.

Beautiful, dramatic, or poetic sculptures could be placed elsewhere (not in the Mall or at the Gates) only if they did not dominate the landscape. Hence the Falconer sits high on a rock overlooking Terrace Drive (72nd Street).

The Halleck Fiasco, 1877

You’ve probably never heard of Fitz-Green Halleck, but in the mid-nineteenth century he was among the most famous American-born poets. One of his best-known works is addressed to his recently deceased friend Joseph Rodman Drake:

Green be the turf above thee,

Friend of my better days!

None knew thee but to love thee,

Nor named thee but to praise ... (more here)

After Halleck died in 1867, William Cullen Bryant, Samuel Morse, Andrew Haswell Green and others asked the Board of Commissioners of Central Park to allow them to erect a sculpture of Halleck on the Mall. Sir Walter Scott and William Shakespeare were already represented. Wasn’t it time to add an American writer? The Board approved the request.

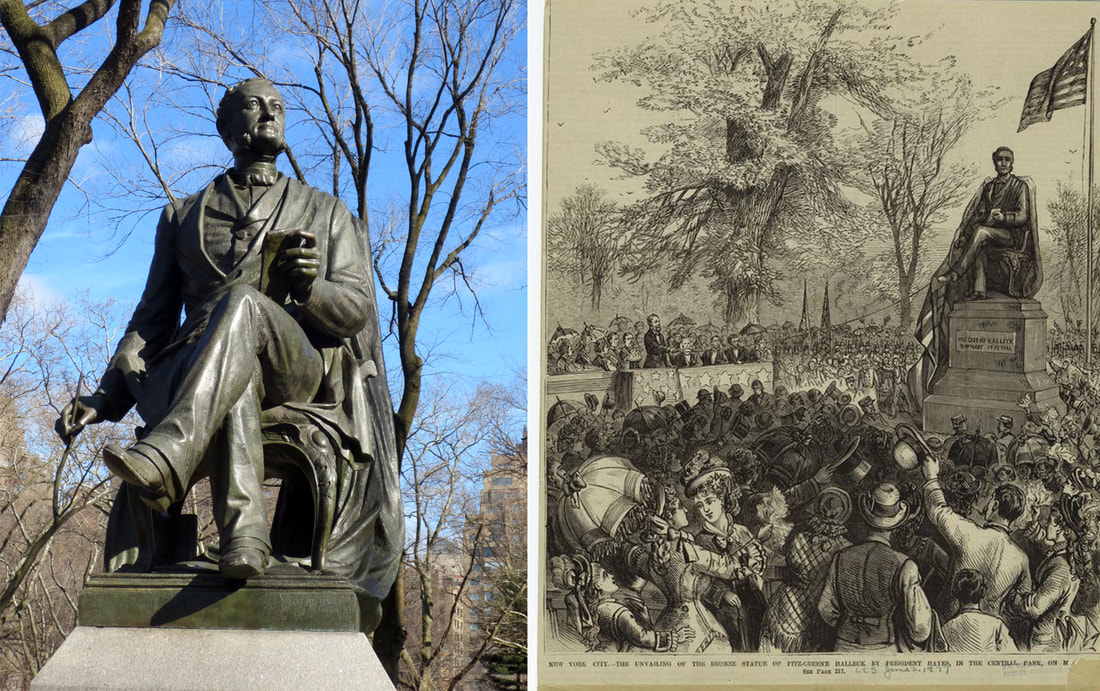

Left: James Wilson Alexander MacDonald, Fitz-Greene Halleck, 1877. Photo copyright © 2017 Dianne L. Durante. Right: Dedication of the Halleck sculpture, 1877. Image: New York Public Library Digital Collections

The trouble began in 1877, when the sculpture had been set in place and was ready to be dedicated. Without asking the Board’s permission, the donors invited Rutherford B. Hayes, who had just been inaugurated nineteenth president of the United States, to the unveiling. The donors requested that several hundred members of the Seventh Regiment escort President Hayes into the Park. They sent out more than two thousand invitations to New Yorkers prominent in politics, the arts, the military, society, and business.

In 1877, the closest most Americans got to the president was an illustration on a campaign poster, or a picture in a book or newspaper. The Halleck dedication was like today’s red-carpet events. Ten thousand people crowded into the Park to get a glimpse of the famous guests. Once in the Park, they trampled the greenery and hauled off armfuls of spring flowers. The Park police smiled benignly: they thought that this day was an exception to the rules against mauling the greenery.

Olmsted was furious. In a report to the Board in 1877, he noted that almost ten million dollars had been spent on the Park. The value of the Park, said Olmsted, is in its natural elements: if those are destroyed, then we lose the value of the artificial elements such as the bridges and the roads.

A much higher degree of beauty and poetic influence would be possible but for the necessity of taking so much space for that which in itself is not only prosaic but often dreary and incongruous, that is to say the necessary standing and moving room for the visitors. —Olmsted, Minutes of the Board of Commissioners for May 1877 to April 1878, pp. 43-48

This is the ultimate in advocating the pastoral aspect: the Park would be a lot better if we didn’t have to allow the public in!

After the Halleck fiasco in 1877, the Board banned any large gatherings in the Park. The prohibition held until the 1970s, when the city invited pop stars such as Barbra Streisand and Simon and Garfunkel to perform there. The concerts drew more than a hundred thousand spectators—and devastated the Park’s grassy areas. With the city floundering financially, drawing people into the Park and the City was considered more important than preserving the Park.

But that’s another story: in the next chapter, we return to the 1870s and the effect of Boss Tweed and his cronies on Central Park.

Dianne L. Durante is an independent scholar, writer, and lecturer who focuses on art history and history, with forays into food, politics, and publishing. Recent projects include three volumes on Alexander Hamilton, Central Park: The Early Years, Innovators in Sculpture (a survey of 5,000 years of art in 2 hours), and two videoguide apps by Guides Who Know.

—

This post is an excerpt from the author's new book, Central Park: The Early Years.