Notes on the Manhattan Purchase

By Richard Howe

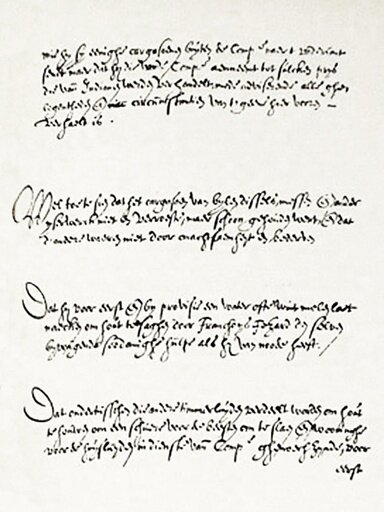

Letter of November 4, 1626, from Peter Schagen in Amsterdam to the States-General in The Hague, reporting the arrival the previous day of the West India Company ship Arms of Amsterdam with news of the purchase of Manhattan.

Christus is goed maar handel is beter.

Christ is good but trade is better.

- 17th century Dutch Proverb

The extant evidence for the Dutch purchase of Manhattan is scant, indirect, and circumstantial. Surviving West India Company documents show that sometime in January, 1625, and again on April 22, 1625, the company authorized — but did not require — the provisional director of its New Netherland colony, Willem Verhulst, to make such a purchase. A letter sent from Amsterdam to the States-General of the United Netherlands in The Hague on November 5, 1626, reported the news that “they” had purchased the island “for the value of 60 guilders” (currently about $1,000). Peter Stuyvesant, who was at least in a position to know, wrote — probably in 1649 — that the early colonists had made many such purchases, Manhattan and Staten Island among them. The deed for Staten Island survives, but not the deed for Manhattan. All in all it’s not much to go on; nevertheless, the scholarly consensus is that the purchase did take place, probably by Peter Minuit, and most likely in mid-May, 1626.

The contract for the purchase of Manhattan has been lost, but it is perhaps not too far-fetched to take the surviving deed to Staten Island as a reasonable proxy for it. Dated August 10, 1630, the deed identifies the eight Native American sellers by name, defines the property and affirms their ownership of it, states that they have received compensation for it, and declares that they

. . . transfer, cede, convey and deliver to and for the benefit of the Honorable Mr. Michiel [sic] Paauw . . . [the] land with its forest, appendencies and dependencies, rights and jurisdiction, belonging to them individually or collectively, or which they might derive hereafter . . . giving him actual and real possession thereof, as well as complete and irrevocable authority and special power, that he . . . may take possession of [the] land, live on it in peace, inhabit, own and use it, also do with it, trade it off or dispose of it, as [he] like anybody else, would do with his own lawfully obtained lands and dominions . .

The deed goes on to explicitly foreclose any subsequent challenges to the sale on the part of the sellers.

Was such a purchase legitimate? That is, did the sellers — the wilden, as the Dutch sometimes called the Native Americans — understand what the buyers meant by it? If not, can they be said to have freely entered into the contract? And if they did not, and the contract was for that reason invalid, doesn’t the land still belong to the sellers’ descendants? This kind of question still haunts the courts today in land disputes with Native Americans, and Minuit’s purchase of Manhattan is still cited in litigation. But it was already a lively issue in early 17th century Europe. Was settlement justified by right of the Europeans’ being a superior and above all a Christian civilization, by right of discovery, or by right of conquest? The Protestant Dutch tended to reject such justifications as so much popery, just as they rejected the earlier papal division of the New World between the Spanish and the Portuguese to the exclusion of anyone else. Or was the question meaningless to begin with, as was argued by many, John Winthrop among them, if the Native Americans had no concept of property in land and therefore could not be said to possess it? English colonial charters, in any event, had no qualms about granting the companies property in land in North America. But the often conflicting legal and theological justifications for settlement soon crumbled in the face of the practical need for something simpler, and that simpler thing was a purchase. Even the Virginia Company cited purchase as the chief justification of its Jamestown claims in 1610, and purchases of Native American land by English colonists in North America were commonplace by the end of the 17th century.

The West India Company did not deny the right of conquest as a legitimate means of acquisition, as evidenced by its designs against the Portuguese in Africa and Brazil or its claiming the booty of privateering as its legitimate property. But the company issued formal instructions to Provisional Director Verhulst in January, 1625, stipulating that

A page of the West India Company’s January, 1625, formal instructions to its newly appointed provisional director of the New Netherland colony, Willem Verhulst.

. . . [h]e shall also see that no one do the Indians [sic] any harm or violence, deceive, mock, or contemn them in any way, but that in addition to good treatment they be shown honesty, faithfulness, and sincerity in all contracts, dealings, and intercourse, without being deceived by shortage of measure, weight, or number, and that throughout friendly relations with them be maintained.

And a few months later, on April 22, 1625, the company again instructed Verhulst that

. . . [i]n case there cannot immediately be found a suitable place, abandoned by the Indians or unoccupied, at least 800 or 1000 morgens [1,600–2,000 acres] in extent, fit for sowing and pasture . . . they shall see whether they cannot, either in return for trading-goods or by means of some amicable agreement, induce them to give up ownership and possession to us, without however forcing them thereto in the least or taking possession by craft or fraud, lest we call down the wrath of God upon our unrighteous beginnings, the Company intending in no wise to make war or hostile attacks upon any one, except the Spaniards and their allies, and others who are our declared enemies.

Verhulst was also twice instructed to remain neutral in any conflicts among the Native Americans themselves, and to punish any colonist who wronged them.

Smart traders soon learn that it pays in the long run to keep a certain distance from suppliers and customers and to remain strictly neutral with regard to conflicts among them. The 17th century Dutch were nothing if not smart traders. By the time they declared the Abjuration of Philip II of Spain and reorganized themselves as the Seven United Provinces of the Netherlands in 1581, the Dutch had learned their merchant catechism well: don’t get involved, never take sides, meliorate conflicts as much as possible, don’t give offense, treat everyone equally and fairly, and get it in writing, if you want your affairs to go as well as they possibly can for you in this vale of tears. Of course, Verhulst’s instructions were in part a matter of expediency and good business sense, of the company’s wishing to prevent disruptive — and expensive! — conflicts if it could. All too often it could not, and the atrocities committed by some of the colonists rank with any in the long and bloody history of the human race, but the company’s position was clear and these acts were against its explicit policy.

It is virtually certain that the Native Americans did not understand the Dutch and English land purchases the same way these Europeans did, at least to begin with, although it did not take them long to catch on, and within a few years such transactions were taking place among the Native Americans themselves. But simply to dismiss these purchases as illegitimate if not downright fraudulent — though of course such things did happen, and not at all infrequently — is to mistake the source of their power. If this was a kind of imperialism, it was an imperialism of a more sophisticated sort than brute conquest or simple deceit: in such transactions the colonists imposed their identity on the Native Americans, dealing with them neither as wilden nor as people of a different but nonetheless valid culture but as proper Dutchmen like themselves. Of course in so doing, the colonists not only reassured themselves of the legitimacy of their presence in New Netherland but also produced documented titles to the land they acquired, recognizable in any Dutch court of law should any dispute ever arise, whether with the sellers or between any subsequent buyers or heirs.

But there is more, I believe, to the Dutch purchase of Manhattan than simple expediency and the wish to avoid conflict, more to it even than the company’s acknowledgement that such contracts may be very useful. The purchase of Manhattan expressed another, deeper, intention, evidenced in the provisional regulations that the first colonists were sworn to abide by before departing Amsterdam for New Netherland on March 30, 1624, which required them

. . . [to] practice no other form of divine worship than that of the Reformed religion as at present practiced here in this country [the United Netherlands] and thus by their Christian life and conduct seek to draw the Indians and other blind people to the knowledge of God and His Word, without however persecuting any one on account of his faith, but leaving to every one the freedom of his conscience . . . .

Freedom of conscience in New Netherland — seven years before Roger Williams! And officially too! But perhaps not so astonishing: although the 17th century Dutch were not immune to the uses of intolerance, particularly when mixed with politics — Johann van Oldenbarnevelt was executed for the militancy of his religious views in 1618 and his ally Hugo Grotius fled for his life in 1621 — there were many who favored toleration among those who had suffered the intolerance of the Hapsburgs or witnessed the devastations of religious warfare elsewhere in Europe. The West India Company’s stand against persecuting anyone on account of their faith, granting to everyone their freedom of conscience — at least in New Netherland — may not have been universally accepted in the Netherlands themselves, but it was also not unprecedented: the Province of Holland had declared itself for toleration already in 1613–1614.

The West India Company had good reason to insist on freedom of conscience in New Netherland. Refugees from the European wars had made the Dutch Republic a multi-cultural melting pot 300 years avant le lettre, and it was principally from the refugee communities, not from the prosperous native Dutch, that the first colonists were recruited. Within 20 years there were not only Calvinists of various persuasions on the island of Manhattan but also Catholics, English Puritans, Lutherans, Anabaptists, and others, altogether said to be speaking 18 different languages among them. The venture could scarcely have been expected to succeed if such a motley crew were not enjoined from quarrelling about religion. Christus is goed maar handel is beter: “Christ is good but trade is better” was the prevailing sentiment, and if nothing else, in these circumstances toleration was good for trade.

“Freedom of conscience” is a profoundly multi-valent expression: objectively, it means being allowed to practice one’s faith openly and without interference from the governing authorities; subjectively it can also mean that one is free to choose how one wishes to express one’s relationship to God in whatever terms one conceives of that relationship — if any — in accord with the dictates of one’s own conscience. Implicit in the latter conception of freedom of conscience is the idea that individuals are, ultimately, free agents who, like Adam and Eve, can choose to sin or not, at least in any particular instance, if not in the totality of them, owing to the baleful effects of original sin. Even if the salvation or damnation of the soul rests on the inscrutable will of le dieu caché, the individual remains free to choose in all lesser matters. In this sense, the freedom of conscience that the West India Company sought to assure the Native Americans — as well as its own colonists — would also impute to them a more general freedom of choice, including the choice to freely enter into contracts for the sale of their lands. Or so an incautious 17th century Dutch theologian might have argued. If the wilden were indeed God’s children and free, however blind to the true religion of John Calvin they might yet be, their identity as they themselves understood it: who they were and what they thought themselves to be, was irrelevant to the conduct of the business at hand. In these terms, the purchase of Manhattan — from the Dutch point of view, of course — was perfectly legitimate, starting from first principles.

Certainly the West India Company had no doubts about it. Within a few years the company was making grants of land, large and small, to its colonists, totaling some 263 that we know of on the island itself and some 362 more elsewhere in New Netherland. It could not have done so had it not been certain of its own title to the lands it was granting. This certainty has survived: the English upheld the Dutch titles to these properties after their seizure of New Netherland in 1664 and despite the confusions resulting from the British occupation of New York 1776–1783, it is possible to this day to trace many Manhattan properties back to their original Dutch title holders in an unbroken chain of conveyances ultimately rooted in the purchase of the island itself. The Manhattan purchase was the primal Manhattan real estate transaction: from it is descended every other Manhattan property conveyance, on down to the present day.

Like all primal acts, the Dutch purchase of Manhattan had consequences unknown and unknowable at the time. As anyone knows who has ever tried to return even a trivial purchase without the sales receipt or had a deduction challenged by the IRS, it is the document of a transaction that sustains the transaction’s continuing legitimacy. The modern social contract rests not only on the tacit agreements that we call culture and the explicit ones that we call law but in everyday practice on the chains of evidence of our transactions great and small. It is characteristic of the modern world, at once both oppressive and liberating, that every individual must be his or her own bureaucrat: the administrator, accountant, and archivist of his or her own life. When Peter Minuit — let us assume it was he — bought the island of Manhattan from the Native Americans for the value of 60 guilders in mid-May, 1626, executing, recording, and filing a contract similar to the one that has survived for the purchase of Staten Island — for let us also assume that he did attend to such necessary administrative details — he not only caused title to the island to be conveyed from sellers to buyers, he also conveyed Manhattan’s future into the nascently modern world: a world in which even then transaction-based legitimacy — a matter of what you are doing and what you have done — was beginning to trump identity-based legitimacy — which is a matter of what you are and where you’ve come from — as the foundation of the social order, with consequences perhaps only just imaginable in 1626 and still unfolding unimaginably even in the world we live in today. This — and not the legend of the $24 worth of beads, nor even the ineradicable obsession of every true New Yorker with local real estate rents and values — is the import of Minuit’s purchase for the history of this city: it was the first step in making New York a place where, paradoxically, just because here identity ultimately doesn’t matter, you can be anyone, even yourself.

Richard Howe is a frequent contributor to the Blotter, and is writing a history of New York as a built environment. He also runs the photographic study New York in Plain Sight: The Manhattan Street Corners.

Further reading

The West India Company documents as cited in this note are to be found in Documents relating to New Netherland in the Henry E. Huntington Library, translated and edited by A. J. F. van Laer (1924), available on-line at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nycoloni/huntoc.html. The deed for the purchase of Staten Island is from Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York, vol. XIII, translated and edited by Berthold Fernow (1881), available on-line at http://archive.org/details/cihm_53996.

An excellent and entertaining account of the purchase and the legends that have developed around it is in Edwin Burrows & Michael Wallace’s Gotham (1998). A good sense of what we do and don’t know and what we might or might not legitimately conjecture about the purchase of Manhattan can be gotten from reading together three articles in the Holland-America Society’s journal De Halve Maen by C. A. Weslager: “Did Minuit Buy Manhattan Island from the Indians?” vol. 43 (1968) and by Charles Gehring: “Peter Minuit’s Purchase of Manhattan Island — New Evidence” vol. 54 (1980), together with Peter Francis, Jr.’s “The Beads that Did Not Buy Manhattan” in New York History, vol. 67 (1986), a later version of which is available on-line at http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/41/415.html (but beware, Francis’ date for the Staten Island purchase incorrectly gives the year as 1626 rather than 1630).

For a lawyerly analysis of the European land purchases in colonial North America and the controversies surrounding them then and now, Stuart Banner’s How the Indians Lost Their Land (2005) is indispensable and a good read too.

For a broader look at the Dutch in Manhattan, there is, besides Burrows & Wallace’s Gotham, Oliver Rink’s Holland on the Hudson (1986) and Jaap Jacobs’ The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America (2009), both of them excellent and readable monographs on the subject. T. J. Wertenbaker’s The Middle Colonies (1938) still rewards serious attention. Russell Shorto’s The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America (2004) puts a lively human face on life in Nieuw Amsterdam.