Notes on the Commissioners' Future City

By Richard Howe

Simeon De Witt

The men whom the New York State Legislature commissioned in 1807 to lay out the streets and roads in the City of New York were not city planners. Only one of the three, Simeon De Witt, had any relevant expertise: he had been trained as a surveyor and held the office of Surveyor General of the State of New York. John Rutherford came from a merchant family in the city and had been a U.S. senator. Presumably he was to represent the city’s merchant interests. Gouverneur Morris was the most prominent of the three: a justly celebrated and respected patriot, he had been a delegate to the Continental Congress, a signer of the Articles of Confederation, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, a member of the committee that drafted the constitution, and a U.S. senator. In 1810, while still serving on the streets and roads commission, he became chairman of the Erie Canal commission as well. What he brought to the commission was clout. The streets and roads commissioners were, in short, political appointees whose job was in the first place a political one: they were to ensure that the city’s merchant interests prevailed over the opposing interests of the big landowners as the city grew northwards up the island of Manhattan.

The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 (in William Bridges’ engraving), showing the built up area of the city downtown (shaded), at that time with a population of 100,000, and the grid up to the Parade Ground for exercising a militia (large green rectangle at the right) with its northern border at 34th Street, which the commissioners conjectured to be the furthermost extent of the of the city by 1861, when the population was conjectured to reach 400,000 (Image: Library of Congress)

The crux of the conflict to be settled was whether the city would have the right to lay out streets and roads on the landowners’ private property and, when the time came, to use its power of eminent domain to acquire the necessary rights of way. The commission and its plan — whatever it might turn out to be — was a means for deciding this conflict in favor of the merchants and for making the decision stick by invoking the power of the state legislature over the city council, where the two factions had been deadlocked on the issue for over a decade. DeWitt Clinton, the mover and shaker behind the commission, was not going to have recalcitrant — not to say greedy — landowners impeding the rapid growth of the great commercial city he foresaw resulting from his great vision of a canal connecting New York with the interior of the continent.

If the commissioners were not city planners, neither were they visionaries, at least not on the scale of DeWitt Clinton and his as yet unbuilt and unfunded Erie Canal. But they were by no means unmindful of their responsibility. They understood that their plan, whatever it turned out to be, could shape the city for decades, even centuries to come, and therefore insofar as possible should meet the needs of the city and its development for decades and centuries to come also. So the commissioners must have had some idea of what their future city would be like, though they had little to say about it in their Remarks to their plan. They mentioned that the city would at some point outgrow its current water supply. It might be attacked again, as it had been in 1776. It would become a city of the first rank, possibly reaching a population of 400,000 in 50 years, i.e., by 1861, by which time its built up area might extend solidly up to their plan’s 34th Street. Its northward growth might eventually meet the southward growth of the village of Harlem, but the rest of the island above the Harlem plain, i.e., above 155th Street would still be sparsely populated even after 200 years or more — “centuries” — and would remain that way “in the course of ages.”

Mitchell’s map, showing the built up area of the city (shaded) in 1846, when the population passed 400,000, fifteen years soon than conjectured by the Commissions in 1811. The northern limit of the built up area has pushed past 14th Street but is still mostly below 21st Street (Image: Rumsey Collection)

On these assumptions the commissioners reserved space for a large reservoir and another, larger, space on which to exercise a militia. And except for Tenth Avenue, extended their plan only as far north as their 155th Street. Since New York was already the most populous city in the United States, what they had to have meant by a city of the first order was, e.g., Lisbon, Madrid, Amsterdam, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, and London, i.e., cities with a population in the range of 200,000–1,000,000, in which company a figure of 400,000 people for New York 50 years hence was very much a middle of the road estimate, neither particularly conservative nor aggressive—assuming, of course, that the commissioners were correct that New York would soon be joining the ranks of the world’s great cities.

To briefly compare the commissioners’ planning assumptions with what actually happened: The city did soon outgrow its water supply. It was not attacked again for nearly 200 years. It did rapidly become a city of the first rank, with a population that passed not 400,000 but rather 800,000 in 50 years. When its population reached 400,000 around 1846 its built up area was only as far north as 21st Street, and most of it was still below 14th Street. Yet it was reaching past 155th street prior to 1900; and up by 1910–1920, it covered the whole of the island all the way up to the new Harlem River Ship Canal, i.e., to 221st Street. It should, I think, be noted that those of the commissioners’ assumptions that are quantifiable did prove to be correct within about a binary order of magnitude, which is actually pretty remarkable for such long range predictions as they were making.

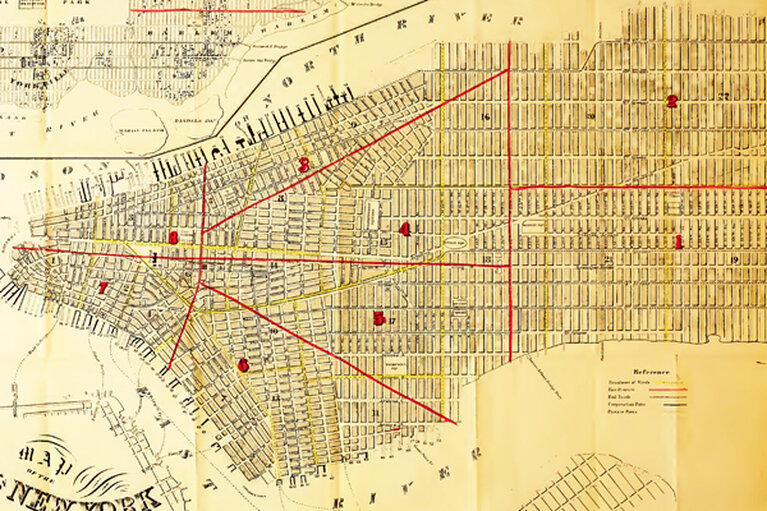

From a 1856 map showing the built up area of the city (shaded) in that year, when the population was passing 6500,000, on its way to just under 800,000 in 1861. The northern limit of the built up area has pushed northwards past 42nd Street and will be approaching 59th Street by 1861. Red lines delineate fire districts, which are also numbered in red. (Image: Valentine’s Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York for 1856)

The commissioners settled on the grid plan for the city which, for better or for worse—opinions vary—Manhattan is still living with, albeit with some modifications here and there, but, all things considered, not so very many. The commissioners wasted few words on their reasons for choosing a grid plan, thus leaving the door open to much speculation ever since, despite their plain statement that it was chosen simply because it facilitated the construction of rectangular buildings, which were the cheapest to construct and the most convenient to live in, besides which they thought the plan would meet with less opposition from the island’s landowners than would any of the alternatives they had considered.

Why didn’t the commissioners say more about their rationale for the plan? It could be argued that after years of vociferous objections by the city’s landowners to all such plans, the commissioners may have felt that the less said the better: the fewer specifics their opponents could latch onto and contest, the less resistance the plan would meet. So expedience in this respect may account in part for their silence. Expedience may also partly account for their choice of a grid: street grids were commonplace, and it is in the nature of the beast — the human animal — to choose the commonplace over the uncommon, the familiar over the unfamiliar, particularly when the stakes are high, as they are when big properties are involved, like those on the island of Manhattan above the built-up part of the city in the 19th century.

And then there is the lurking suspicion that the plan as drawn—it was actually just a big map—stretching a street grid across the whole of the island, from river to river and from just above the existing city up to a planned 155th Street, with no regard for the island’s shoreline, terrain, watercourses, and wetlands, was also a matter of expedience, but of a different kind. After so many delays occasioned by the landowners’ lawsuits and even violence against the surveyors trying to get the island properly surveyed since they were first commissioned by the legislature in 1807, by November, 1810, the commissioners had simply run out of time: the April 3, 1811, deadline set for them by the legislature was fast approaching. The best they could do would be to meet the letter if not fully the spirit of their commission, as Gouverneur Morris wrote to New York Mayor Radcliff on November 29, 1810. With only a few months to go, and with a huge map yet to be drawn—by hand, in three copies — there simply wasn’t enough time left for the commissioners to take into account the island’s shorelines, terrain, watercourses, and wetlands. And it was taken for granted from the outset that the plan would not respect the property lines of the landowners—indeed if anything was the commission’s not very well hidden agenda, that was it. The plan the commissioners submitted was a bureaucratic expedient, so to speak a quick and dirty, done under the pressure of a deadline that had been carved in stone before anyone knew how difficult and time-consuming the planning process would turn out to be.

The plan that the commissioners submitted in 1811 may not have fully carried out the spirit of their commission, but it is reasonable to assume that it fairly represents their thinking about what the future city would be like. That the city of the future is built in the present, using the materials, methods, and tools of the present was as true in 1811 as it is today. Such things tend to change only very slowly, so what carpenters, masons, roofers, plasterers, or glaziers are using at any given point in time is generally not much different from what was used by their predecessors. Absent any radical changes in materials, methods, and tools, the city of the future will closely resemble the city of the present. The commissioners’ future city of New York would be the 1811 city of New York that they knew, only bigger, much bigger.

That city would not only be bigger, on the commissioners’ conjectures it would be twice as crowded in 1861 as it was in 1811: 400,000 people in the six square miles below 34th Street amounts to just over 100 people per acre, as against just over 50 people per acre in the built up part of the city below North (now Houston) Street in 1811. The future city would still be a major seaport, and transportation to and from it would still be a matter of wind and sail, though Fulton’s steamship had already given a glimpse of the future in 1809. Transportation within the city would be, as always, horse, mule, or ox powered. New York in 1811 was a predominantly wooden city, and it was only to be expected that most buildings in the future city, especially the smaller ones, would also be built of wood, except for the now mandatory masonry hearths and chimneys. Some buildings would have brick facades, and some stone, but behind their elegant facades they would still be timber framed. Most of the buildings in the city would be no more than about 25 feet wide—a width dictated by the tensile strength of timber joists supported only at their ends — and would eventually stand cheek by jowl where they did not actually share party walls. An increasing number of buildings would have exterior load — bearing brick walls instead of timber framing, but again, their interior construction would be almost entirely of wood. Most of these buildings would be no more than three or four stories high, owing to limitations in the supply of brick: as a rule of thumb, doubling the height of a load-bearing brick wall would quadruple the number of bricks required to support the additional load. The industrialization of brick making did not get underway in earnest until the 1850s, after which the average height of these buildings began to increase to five and six stories. As in 1811, the future timber-framed buildings would rarely go above two or three stories—three or four with the attic included.

Broadway between Duane and Pearl Streets in 1807, with two and three story wood-frame houses. (Image: Valentine’s Manual for 1865)

Wood, brick, and, to a much lesser extent, stone—these were the materials the city would be built with: there was simply nothing else on the horizon. Iron, steel, and concrete construction did not begin to take hold as building materials until relatively late in the 19th century and did not begin to make real headway in displacing wood and brick in the city’s building stock until well into the 20th. Even today some 24,000 of Manhattan’s roughly 42,000 buildings are brick and wood survivors from eighty to a hundred and more years ago. What the commissioners had in mind as their image of the future city — all that they could possibly have had in mind — was a city built largely of wood; even its brick buildings would be no more than shells supporting an interior built of wood.

Broadway and Marketfield Street in 1798, with two and three story wood-frame houses (Image: Valentine’s Manual for 1865)

Ruins of Trinity Church after the Great Fire of 1776 (Image: Valentine’s Manual for 1865)

A wooden city is a conflagration waiting to happen: the Rome that burned while Nero apocryphally fiddled was the wooden Rome, not the marble one; wooden London burned catastrophically in 1666, wooden Moscow in 1812, wooden Chicago in 1871 — the list is as long as it is sad. Fully a fourth of wooden New York burned in 1776, and large parts of it downtown would burn again in the “Great” fires of 1835 and 1845. Lesser but still serious fires were a constant threat: the city reported 25 of them in 1810 and 26 in 1811. Fifty houses had been lost to a single fire in 1796, and 40 in 1804. In between, a whole block and more had burned in 1801. In May, 1811,just two months after the commissioners submitted their plan, as many as a hundred buildings were lost to a fire. In 1811 there were still few water mains and no great reservoirs to supply them, there were no fire hydrants, and the manually pumped fire engines were supplied with water by bucket brigades.

In a charming memoir of the commissioners’ work, written some 50 years later, their chief engineer and surveyor, John Randel, Jr. — who I rather suspect but cannot prove was the real author of their plan — recalled that the grid was meant in the first place to contain the inevitable fires in the future wooden city: its 60–100 foot wide and closely spaced cross-streets and avenues would serve as fire lanes, providing enough separation between blocks that few if any fires were likely to make the jump from one block to next. And the blocks were small enough to limit the risk that remained. No street plan could by itself prevent fires—New York’s 19th century average ran to about one fire per year for every 1,200 residents, 50,000+ fires in the course of the whole century—and whole blocks might burn, but the 1811 plan would prevent the kind of disastrous fire the city had experienced in 1776, the consequences of which had dogged the city for years thereafter. Despite the grim and ever present reality of fire, the city would continue to stand: it was not fireproof, but it was conflagration proof. About this, at least, the commissioners were right. And partly for this reason the 1811 Commissioners Plan for the City of New York has cast such a long shadow over the subsequent history of Manhattan, on down to the present day. That shadow is the shadow of wood, the shadow of the vanished wooden city and the vanished forests with which it was built.

Looking northwest across the intersection of Broadway and 32nd Street in 2006, near the commissioners conjectured northern limit of the city in 1861. (Image: Author)

Richard Howe is a frequent contributor to the Blotter, and is writing a history of how New York was shaped by the materials used in its construction: wood, stone and brick, iron and steel, concrete, and glass.

Further reading

Hillary Ballon’s The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan 1811–2011 (2012), has done all students of New York’s history a great service by gathering together between two covers of a book the most important documents—texts, maps, drawings, photographs—related to the making of the grid and its subsequent history, thereby sparing us the difficulty of shuttling back and forth between so many disparate sources, the usual bane of this kind of historical research. Simply indispensable—and beautiful too.

Margaret Holloway’s biography of John Randel, Jr., The Measure of Manhattan (2013) is an entertaining and marvelously informative account of the genesis of 1811 street plan and the surveying of Manhattan.

Nineteenth century New York City Clerk David T. Valentine’s Manuals of the Corporation of the City of New York often included maps showing the extent of the built-up part of the city; the Manuals are altogether a rich source for early New York City history.

Two classic studies of the 1811 plan are Edward K. Spann’s “The Greatest Grid: the NewYork Plan of 1811” in Two Centuries of American Planning (1988), and Peter Marcuse’s “The Grid as City Plan: New York City and laissez-faire Planning in the Nineteenth Century” in Planning Perspectives (1987).

Reuben Rose-Redwood’s dissertation, “Rationalizing the Landscape: Superimposing the Grid Upon the Island of Manhattan” (2002) offers a wide-ranging and epistemologically oriented analysis of the grid, and Rebecca Shanor’s The City That Never Was (1988) provides a rich account of its subsequent history.