Irving Berlin in Chinatown

By Samuel Backer

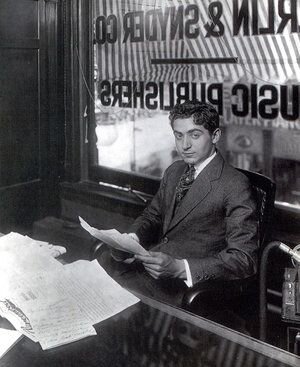

Irving Berlin as a young man

Few individuals are more closely associated with the development of 20th century American music than lyricist and songwriter Irving Berlin.[1] From the early 1910s, when he was first launched into the stratosphere by era-defining pieces like “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” until the late 1950s, when his success finally dried up, Berlin remained at the forefront of the nation’s burgeoning music industry.[2] Over that period, he not only survived a remarkable number of trends and fads, but mastered them all, scoring massive hits with radio ballads, Hollywood showstoppers, Broadway musicals, and patriotic marches.[3] He wrote a startling number of genuine classics, including still-famous songs like “Blue Skies,” “White Christmas,” and “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” In doing so, Berlin helped to create what is known as “The Great American Songbook” — a set of versatile, sophisticated compositions that have served as the harmonic bedrock for much of the Jazz and Pop recorded since.

Berlin’s career coincided precisely with the rise of New York as the corporate and aesthetic center of the American entertainment industry. For much of this period, live theater remained dominant over the still-fledgling cinema. The circuits that controlled the vast majority of performers touring throughout the nation were based in midtown Manhattan, where they organized art with the cutting-edge tools of office bureaucracy.[4] Theatrical productions and vaudeville acts required music, and by the turn of the century, a bustling industry, nicknamed “Tin Pan Alley” for the handful of noisy blocks in which it was headquartered, had developed to provide it. Tin Pan Alley’s publishing houses revolutionized the music industry by focusing on producing and selling “popular” songs to average Americans.[5] Over time, Manhattan became the proving ground for a nation’s music. A hit here could easily translate into massive sales throughout the country, as touring acts introduced such tunes to consumers in theater after theater. Every level of the city’s nightlife was transformed by this newfound proximity to the production of mass culture. During the early decades of the 20th century, the two were so tightly fused that one cannot be analyzed without an understanding of the other.

The tightly packed publishers of Tin Pan Alley

In the years since it first emerged, evaluations of Tin Pan Alley have remained contradictory. On one hand, some of the music produced by the industry is considered a high point of 20th century culture, a distinctively American sound that reflected the drive and style of a nation coming into its own.[6] On the other, publishers are criticized for running “song factories” that turned out soulless, disposable products that relied on a vast promotional apparatus to gain their popularity and supplant both “high” culture and “folk” tradition.[7] Another viewpoint is that Tin Pan Alley functioned both as a rationalized industry dedicated to the creation of cultural commodities and an expression of local traditions and experiences. In addition to being an entertainment capital, Manhattan was also a unique urban space with a distinct social geography.[8] Rather than a top-down imposition, the production lines of popular music publishing were intimately bound to the performance practices and cultural dynamics of turn-of-the-century Manhattan. By focusing on this social geography — in essence, by re-provincializing New York — it is possible to reexamine the history of Tin Pan Alley. The career of Irving Berlin offers an ideal place to begin such an effort.

Berlin was born in 1888 in Tyumen, a town in Siberia, where his father had found work as a cantor for the town’s small Jewish population.[9] Soon after, Berlin’s family — father, mother, and seven other siblings — immigrated to the United States, arriving in New York’s Lower East Side in 1893. Berlin’s life assumed the structure of an O. Henry story as the boy, facing destitution, took to the streets to earn a living. Sharp-witted and hard-working, he spent his teenage years busking for change. He picked up odd jobs as a chorus boy and a vaudeville extra before finding steadier work as a singing waiter in a notorious Chinatown saloon. From there, he began writing songs, and was eventually hired by the up-and-coming publishers Waterson & Snyder. Within a handful of years, he was made a partner, and soon after that, became the founder of his own successful company.

Chuck Connors, who billed himself as “Mayor of Chinatown”

In the historical and musicological work exploring this remarkable rise, Berlin’s early years in New York have been mined heavily for picturesque detail.[10] In Chinatown, the young musician worked as a singing waiter at the Pelham Café, a saloon owned by Mike Salter, a Russian Jew, small-time criminal, and low-level Tammany Hall associate popularly known as “N****r Mike” for his dark features and curly hair.[11] Here, the future composer of “God Bless America” earned money by belting out popular hits and risqué parodies. Along the way, he encountered a string of legendary turn-of-the-century New Yorkers: Chuck Connors, the white “King of Chinatown” who made his money organizing “slumming” expeditions for elites who wanted to see how the other half lived, “Chinatown Gertie,” a notorious opium addict who lived off the donations of horrified tourists, and “Dippy” Rice, a gangster famous for being unable to successfully kill himself.[12]

The outside of the Pelham Café

While these years are foundational to the Berlin legend, they’re often overlooked when considering the development of his musical skills. Far from being a backwater, the Pelham Café was a hothouse for the development of a new type of metropolitan entertainment. In place of the class-stratified urban entertainment of the late 19th century (with the exception of venues linked to ultra-masculine “sporting” culture), commercial spaces like the Pelham Café created new zones of interaction for a cross-class audience brought together by individual desires for consumption.

In spite of its name, Salter’s café is more accurately described as a dive bar or a saloon. Pell Street, on which the business was located, served as a link between the ethnically and socially distinct neighborhoods of the Bowery, the center of white, working-class entertainment culture, and Chinatown, simultaneously a growing ethnic enclave, a business center, and a tourist destination. As the Evening World described it, Pell was “a canyon path gashed out of a motley lot of stone, brick and frame houses to serve as a back alleyway for the ragtag and bobtail human derelicts of a great city.”[13]

At the turn of the 20th century, immigrant neighborhoods such as New York’s Chinatown had become increasingly important for the elaboration of new modes of pleasure and identity by visiting “slummers.”[14] The prosperous white men and women who flocked to such spaces intentionally embraced the supposedly innate “otherness” of the locals on display and used the “exoticism” of their surroundings as an excuse to explore a range of sexual and social pleasures, discovering new ways to eat, drink, and flirt while temporarily beyond the bounds of upper-class respectability. Slumming reflected a number of longstanding tendencies in American culture, most obviously, the tradition of racist minstrel shows, in which white audiences looked for freedom through black alterity. It is no coincidence that the peak of slumming coincided closely with an enormous popular fad for “coon songs,” which carried blackface from the theater into the family home.[15]

Salter was eager to cultivate such wealthy patrons and designed the Pelham Café to attract thrill-seekers looking for an “authentic” experience. This didn’t mean it failed to attract customers who lived or worked in the area. While the business barred Chinese (and presumably Black) patrons, it successfully catered to rough elements from the nearby Bowery, including a steady stream of local criminals and gangsters.[16] Inside the café, there was a backroom for music by performers like “Bullhead,” a singer somewhat older than Berlin, and “Professor” Mike Nicholson, a pianist.[17] “It is long and narrow,” a reporter for the World explained. “The professor sits at the ragtime box in the corner. Tables line the walls, and the centre of the soiled pine floor is reserved for spielers.”[18] Irving — then known as Izzy — worked as one of these spielers, “entertaining the customers with song and recitation” while taking orders and delivering beer.[19] The description of the piano as a “ragtime box,” linking the Pelham Café to what was widely understood as a Black music, further suggests the racialized aspects of the experiences sought by the slummers.[20]

Unlike the jostling familiarity of a bar or crowded concert saloon, the juxtaposition of the seated audience and the vacant performance space established a degree of separation among the crowd. Like the cabarets that would soon develop further uptown, this spatial environment made it possible to watch and be watched without fully participating, rendering the audience an integral part of the show.[21] This dynamic cut both ways — not only did slummers get a look at working-class New Yorkers, but the citizens of the Bowery had an equal chance to observe the “swells.”

Berlin playing Piano, 1906

Berlin cut his teeth as a performer and songwriter in front of these self-consciously diverse crowds. Singing waiters performed for tips, which were thrown into the center area. To make a living, Berlin had to use all of his wits and skills to win over a varied and sometimes violent audience. “A waiter learns an awful lot about people,” Berlin later recalled. “He gets a course in advanced psychology that it takes a lot of living to get any other way.”[22] Berlin’s performances also helped prepare him a life in songwriting, providing a deep-seated understanding of what did — or didn’t — make a tune or a lyric click with patrons. Berlin didn’t make the leap directly into original composition, however. Instead, he developed his lyrical facility through song parodies.

Putting new, often sexually explicit words to existing music was a longstanding tradition in New York’s bars, taverns, and concert-saloons. Such places, the Pelham Café likely included, were often closely linked to the sex trade, and remaking popular songs to accentuate their bawdy, boisterous qualities made excellent business sense.[23] More generally, in an era before records and radio, when most musical texts were disseminated through published sheet music, few songs had anything like the fixed forms associated with popular music today. Compositions often had numerous verses, only some of which any given listener was likely to know. Similarly, the longstanding genre of “songsters,” cheaply published pamphlets that contained only lyrics, frequently based new songs around well-known tunes. Ragtime, just beginning to sweep through the nation, was often based on a similar act of repurposing, as pianists upended familiar melodies with unexpected syncopations. In this milieu, the line between original and parody was vague, and performers could easily move between well-known words and their own unique interpolations.

Parodies gave a singing waiter like Berlin ample freedom to experiment. “He was original in his methods and he wrote his own songs,” explained newspapers. “Scarcely any subject came up in the news of the day that he did not put into doggerel verse, pick out a tune for… and sing for the edification of the visitors that called that evening.”[24] The teenager began to hone his sense of rhythm and meter, as well as well his knack for American diction, in the low-stakes environment of the Café. “In the old days when I began to make songs, I didn’t know English well enough to trust myself,” explained Berlin to a reporter. “I took refuge in the vernacular, spelling the words roughly as they sounded—‘whattle’ for ‘what will,’ ‘gonna’ for ‘going to.’ The music I picked out with a finger of two on pianos in the back rooms of café’s where I worked.”[25] Such experiences laid the ground for stylistic innovations that would define Berlin’s legacy. Irving was far from the only songwriter to get his start in this fashion. “Every important songwriter in America… originally started as a parodist,” Tin Pan Alley hitmaker L. Wolfe Gilbert declared, “Writing verses on the other fellow’s songs… you learned rhythm, you learned to write all sorts of melodies, and all the rhythms of the melody.”[26] Rather than coming to songwriting from the outside, these musicians learned their trade within the structures of Manhattan’s musical environments.

The importance of parodies to the education of songwriters in early 20th century New York was only one way the city’s rapidly developing entertainment industry developed a deep pool of local talent and experience. Plugging, in which music publishers hired singers and pianists to perform their songs at venues around the city, was another important pathway for burgeoning songwriters such as Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, and Berlin himself. Similar to song parodies, plugging taught songwriters the ins and outs of what made a hit, helping them to fine-tune a sense for the seemingly small changes — a repeated phrase, a cadence, a shouted interjection — that could set a tune apart.[27]

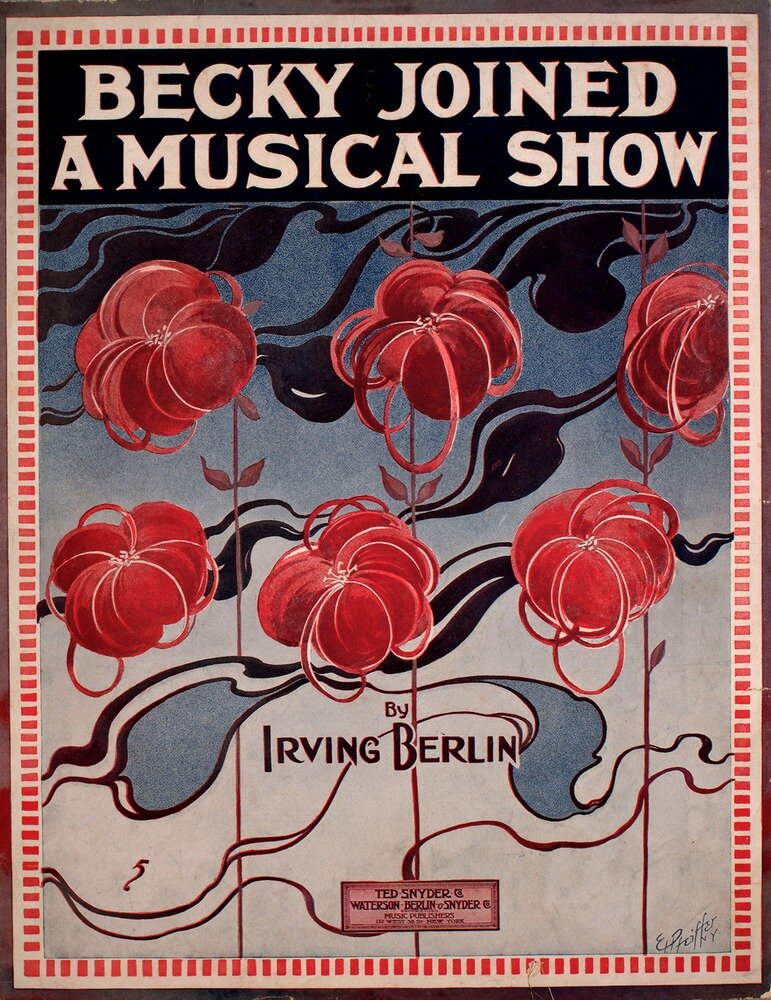

Johns Hopkins' Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection

As a generation of songwriters trained in New York’s saloons and vaudeville halls worked their way up the ranks of Tin Pan Alley, they brought this knowledge with them. Berlin first gained professional attention when Salter, jealous that a rival saloon had published a successful song, tasked Irving with coming up with a hit of his own.[28] While “Marie from Sunny Italy,” the song Berlin composed, didn’t catch the public ear, it was his first step towards musical success. In 1908, Berlin left the Pelham Café for a job at Jimmy Kelly’s, a more respectable saloon uptown, where he would further sharpen his lyrical and melodic skills. Vaudeville performers frequently drank at the establishment, and Berlin began to place songs with them. He started rooming with Max Winslow, a songwriter for the Harry Von Tilzer publishing company.[29] Soon they were collaborating, and Berlin was on his way.

Johns Hopkins' Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection.

American popular music at the turn of the century vacillated wildly between “respectable” parlor songs and ballads and the explicit racism of “coon” or “ethnic” songs. While the former followed the dictates of romance, nostalgia, and sentimentality, the latter adopted an often- horrifying racial masquerade in order to safely present white listeners with the illicit pleasures of sex and rebellion. The music produced by writers like Berlin began to work around such divisions. Playing tunes for wildly different sets of patrons, and constantly revamping them with current events or humorous asides, performers gradually blended categories until a new synthesis emerged. By fusing the swing of ragtime, the innuendo of minstrel-show songs, and the sentiment and romance of ballads, Berlin found that he could write music simultaneously universal in its sentiments and grittily real in its particulars, whether explaining that “Becky Joined a Musical Show” or invoking “maidens pretty from Jersey City.”[30] This influential mixture not only originated in New York, but was a direct result of the distinct social and cultural environments that defined entertainment in the city.

“The songwriter,” explained Berlin in an early interview, “depends on the public.”[31] But not just any public. By considering the relationship between Berlin and the settings where he first learned his craft, it is possible to see the enormous role of New York in shaping the development of the American music industry. Revisiting the Pelham Café and the teenage parodist who worked there offers us a new insight into the origins of modern popular song.

Samuel Backer is a PhD Candidate in History at Johns Hopkins University, where his work focuses on the intersections between art, culture, and capitalism. He is also a podcast producer and journalist, with work published in Jacobin, Afropop Worldwide, Africa is a Country, and Red Bull Music Academy Daily. Sam is currently co-host of 'Money 4 Nothing,' a podcast exploring stories of music and capitalism.

[1] “Irving Berlin has no place in American music,” wrote composer Jerome Kern. “He is American Music.” Kern quoted in James Kaplan, Irving Berlin: New York Genius (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 8.

[2] Kaplan, Irving Berlin, 319.

[3] Phillip Furia, Irving Berlin: A Life in Song (New York: Schirmer Trade Books, 1998), 2.

[4] For a detailed examination of these circuits, see Arthur Frank Wertheim, Vaudeville Wars: How the Keith-Albee and Orpheum Controlled the Big-Time and Its Performers (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

[5] David Suisman, Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 18–89.

[6] Philip Furia and Michael Lasser, America’s Songs: The Stories Behind the Songs of Broadway, Hollywood, and Tin Pan Alley (London: Routledge, 2006), xxvi.

[7] The long-term roots of this critical position are discussed in Keir Keightly’s “Tin Pan Allegory,” Modernism/modernity, vol. 19, no. 4 (Nov. 2012): 717–736. The classic elaboration of this idea emerges in “The Culture Industry” in Theodore Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, Translated by John Cummings (New York, Continuum Publishing Press, 1972). Suisman, Selling Sound, 51.

[8] The relation of Tin Pan Alley to the broader structures of Manhattan’s entertainment industry is explored by Jane Mathieu in the innovative article “Midtown, 1906: The Case for an Alternative Tin Pan Alley,” in American Music, vol. 35, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 197–236.

[9] Furia, Irving Berlin, 6.

[10] Most biographies of Berlin repeat the same handful of stories. The book that best connects these early years to his musical output is Charles Hamm, Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot: The Formative Years, 1907-1914, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

[11] Laurence Bergreen, As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin (New York: Viking, 1990) 49-52; New York Evening World, Jan. 17, 1913.

[12] Furia, Irving Berlin, 18–20.

[13] New York Evening World, Jan. 13, 1906, p. 10.

[14] Chad Heap, Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885–1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 17–101.

[15] James J. Dorman, “Shaping the Popular Image of Post-Reconstruction American Blacks: The ‘Coon Song’ Phenomenon of the Gilded Age,” American Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 4 (Dec., 1988): 450–471.

[16] “Robbed Man’s Memory Hazy,” New York Times, Dec. 5, 1906, 9.

[17] Laurence Bergreen, As Thousands Cheer, 37–38. This layout was fairly standard for many such “free-and-easies,” often for legal reasons. For a detailed examination of the concert saloon of this period, see Brooks McNamara, The New York Concert Saloon: The Devil’s Own Nights (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[18] New York Evening World, Jan. 13, 1906, p. 10.

[19] Description from “Won Wealth for a Song,” Tampa Tribune, July 24, 1910, p. 19, a wire service profile.

[20] Douglas Gilbert, The Product of Our Souls: Ragtime, Race, and the Birth of the Manhattan Musical Marketplace, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015). 99–132; Dale Cockrell, Everybody’s Doin’ It: Sex, Music, and Dance in New York, 1840–1917 (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2020), 85–104. On ragtime as a Black form of music, see for example “Fall Styles in Song,” Anaconda (Mont.) Standard, Nov. 9, 1898, p. 7.

[21] Lewis Erenberg, Steppin’ Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, 1890–1930, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 112–142.

[22] Quotation in Furia, Irving Berlin, 18.

[23] Cockrell, Everybody’s Doin’ It, 65–127.

[24] “Won Wealth for a Song,” p. 19.

[25] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 21, 1928.

[26] “Reminiscences of L. Wolfe Gilbert” (1958), Popular Arts Project, Columbia University Oral History Archives.

[27] Furia, Irving Berlin, 30-31.

[28] Bergreen, As Thousands Cheer, 58–62.

[29] Kaplan, Irving Berlin, 53.

[30] Furia, The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Great Lyricists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 26–28.

[31] “New York Waiter Now a Composer,” The Evening Missourian (Columbia, Missouri), August 7, 1910, p. 4.