Imitation Artist: An Interview with Sunny Stalter-Pace

Interviewed by Katie Uva

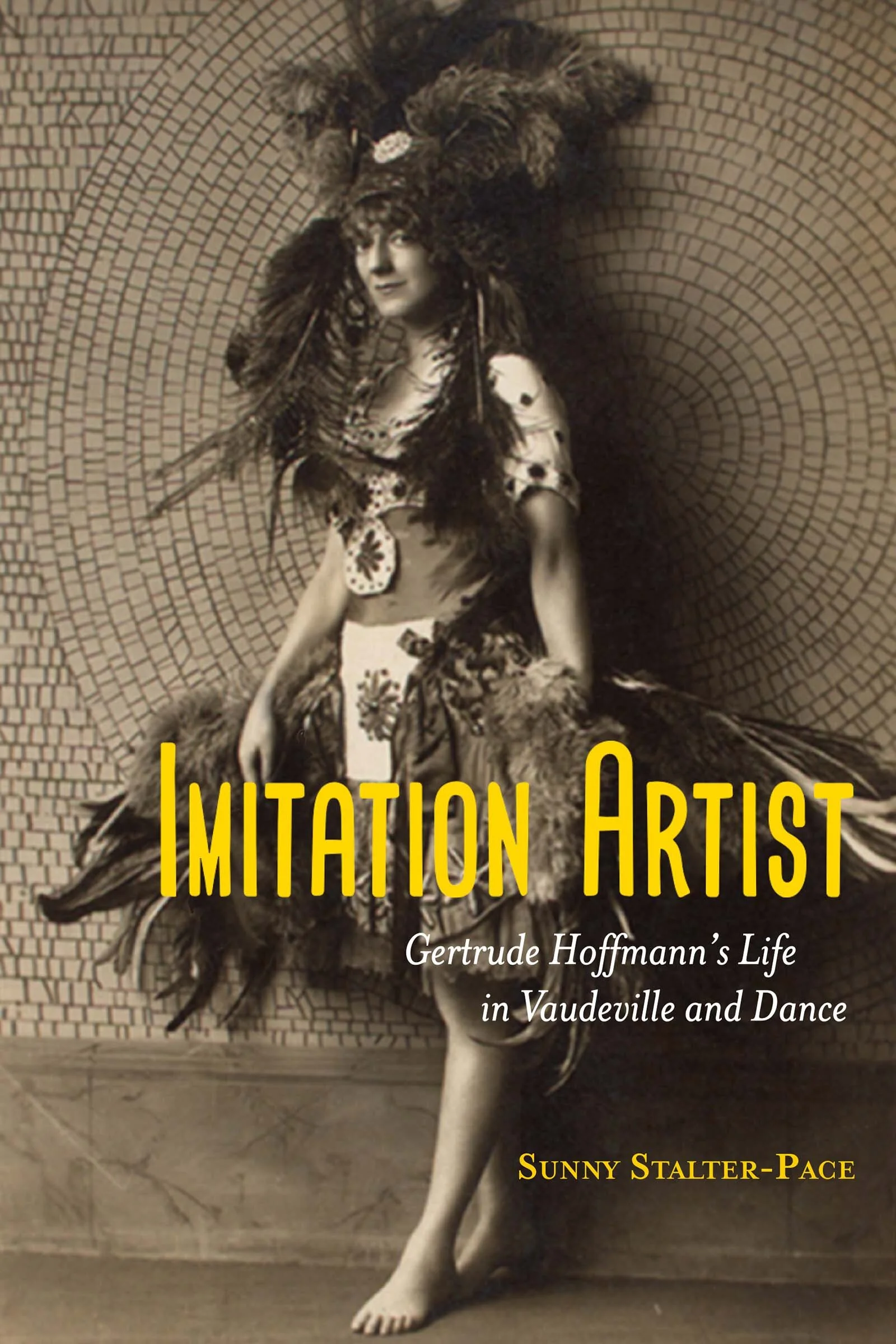

Today on the blog, Katie Uva talks to Sunny Stalter-Pace, author of the recently published Imitation Artist: Gertrude Hoffmann’s Life in Vaudeville and Dance. The book examines the life and times of Gertrude Hoffmann, an early 20th century dancer and choreographer whose career highlights the intersections of high and low culture in the performing arts of that era.

You note in the introduction that Gertrude Hoffmann is someone who “brazenly mixed” highbrow and lowbrow culture. Can you give some examples of how that played out in her work?

Imitation Artist: Gertrude Hoffmann's Life in Vaudeville and Dance

By Sunny Stalter-Pace

Northwestern University Press, 2020

280 pages

Hoffmann was celebrated as a vaudeville comedian and mimic. She first got famous imitating Broadway stars of the day like Eddie Foy and Anna Held. Willie Hammerstein, who ran the Victoria Theatre, asked Hoffmann to copy a more cultivated performance. She traveled to London in the spring of 1908 and watched Maud Allan’s “Vision of Salome,” an interpretation of the “Dance of the Seven Veils” that was very much influenced by the Oscar Wilde play and Richard Strauss opera. Hoffmann was an experienced stage manager and dancer, so she managed to copy the set, costuming, and choreography in extensive detail. She performed the imitation “Vision of Salome” on the Victoria’s roof garden stage that summer. Although Hoffmann’s pantomime was mostly performed in a straightforward way, she ended with some moments that poked fun: kissing the prop head of John the Baptist in an exaggerated way and then ungracefully flopping to the ground.

My favorite example, and the one that made me want to write a book about her, was her show that she called La Saison des Ballets Russes. She saw Sergei Diaghilev’s well known Russian ballet company in Paris and wanted to bring them to the U.S. to perform. They were booked for a stint in London and couldn’t come, so Hoffmann produced and performed in a tour that showed off several of their dances — without getting permission to do so. Critics in New York City already thought this was brazen, not just because it was piracy but because she was a lowly vaudevillian tackling this exalted art form. She emphasized that mix of high and low even more on the road. When the show was losing money, she added her imitations to the bill between the second and third ballets.

How does Gertrude Hoffmann’s career highlight obstacles and opportunities available for women in the early 20th century performing arts?

It was definitely a time period when women could work their way up, to a certain degree. She started as a “ballet girl” — less a dancer and more a glorified extra — in San Francisco operas in the 1890s. One thing that stood out was her interest in working behind the scenes as well as performing. She helped train her fellow ballet girls, and once she moved to New York City she was hired as a dance director and stage manager. This was an incredibly rare position for a woman to take; magazines and newspapers wrote stories about it.

Hoffmann took pride in her management of female dancers, saying that she could do every step she asked them to do. She was also much more sympathetic to the needs and experiences of women in the performing arts, such as child care. But she was also cognizant of the assumptions about sexual availability that men in the audience made about actresses, dancers, and especially chorus girls. When she performed, wealthy men would sometimes ask her to come back to their hotel rooms; when she visited, she brought her husband.

All of her work behind the scenes also helped once Hoffmann stopped performing herself. She ran a dance school and trained young women to perform in the revues and cabaret shows that were incredibly popular in the 1920s. She was a kind of den mother to them, making sure they didn’t drink, smoke, or go on dates. So there were a lot of opportunities for women to perform in the early 20th century, but there were a lot of risks that went along with them.

Gertrude and her soon-to-be-husband Max made the move from San Francisco to New York in 1901. How did New York’s scene provide them with more opportunities?

I think they got a lot of work in New York because they came as a package deal: Max could arrange the music and conduct, while Gertrude could train the dancers and perform. There were new venues sprouting up all over New York at this time in the form of roof gardens. Before theaters were air conditioned, they tended to go dark over the summer. Many of the Times Square theaters built open-air rooftop performance spaces that could be used during the summer time for light, comedic revues. Roof gardens were perfect places to see the kind of shows the Hoffmanns specialized in.

They both made connections to important New York-based producers early on. Oscar Hammerstein I (grandfather of the composer) hired Gertrude. Hammerstein preferred opera, but he opened important vaudeville theaters as well. Max served as music director for Florenz Ziegfeld well before the Follies. They had an especially tumultuous relationship with Ziegfeld — he tried to have Max thrown in jail for a contract dispute! — but he was instrumental in both of their careers.

What was Gertrude’s New York like? Where did she spend her time? How did the city shape her career?

She spent almost all of her time in New York around Times Square working in theaters and nightclubs. Her diaries include some fascinating details about the development of midtown Manhattan, like seeing them dig the trenches for the subways. The area really grew with her career. She adored Oscar Hammerstein I, and not only because he hired her as a dance director. In her eyes, it was Hammerstein building and supporting so many performance venues in the area that made the Theater District what it was.

Water really inspired her too. When she wanted to change her image to something more serious and aesthetic, she had new portraits made where she was dancing on the beach in a Grecian dress and posing on a wrecked ship. I assume she felt a real connection to the coastal areas from growing up in San Francisco. As soon as the Hoffmanns could afford one, they bought a house near the ocean – first in Sea Gate, Brooklyn and then in Freeport, Long Island. Freeport had the additional benefit of being the most popular suburb for stage actors to spend their summers. Freeport had a club for performers called the LIGHTS Club, which stood for Long Island Good Hearted Thespians Society.

Some of the early shows she was connected with, like “At Gay Coney Island” and “A Trip to Chinatown” seem to be notably local in focus. What can you tell us about New York as a topic and setting for theatrical productions in this era?

Early 20th century musical theater was not super focused on telling a coherent story. New songs and dance routines were regularly swapped in and out depending on what came into fashion. Settings for these shows tended to be ones where lots of varied and picturesque things could happen — either entertainment districts or “exotic” neighborhoods where different types of people would mingle. That way, the performers would have a justification for extensive costume changes or presenting musical numbers in different styles.

Even shows that were nominally set in one part of the city might talk about another part of it, though; A Trip to Chinatown included a song called “The Bowery” about a tourist who goes to the Bowery and is totally baffled by it. Showing off different parts of New York City was useful in shows with a mixed audience. The out-of-towners could feel like they were getting a guided tour, and the locals could feel native pride (and maybe a little superiority over to the rubes onstage).

These turn of the century shows inspired Gertrude Hoffmann for quite a while. Her last solo vaudeville act in 1919 included a number called “A Trip to Coney Island” where she played instruments in the orchestra pit that imitated different rides and games. But my absolute favorite local setting was in one of her revues. She set a song and dance number at an “Entrance to the Express Station of the New York Subway” and then on a subway platform during rush hour. Chorus boys and girls played the advertising mascots you would have seen on posters in the stations and on the trains, like the Old Dutch Cleanser Girl and the Cream of Wheat Man. My first book was about modernist literature set on the New York City subway, so I wish I could have seen how she depicted it. You can find the program including that routine on the New York Public Library Digital Collections site here.

You describe the process of “Hoffmannization” as a “whitewashed sound and performance style.” Can you speak a bit more to the popular appetite at this time for music that originated with Black writers and performers but was mediated through white performers?

Max Hoffmann worked for a sheet music publisher in the ragtime era. In addition to writing songs for them, he transcribed the syncopated versions of songs he heard in bars and nightclubs so they could be published along with the regular versions. So that was definitely one market for Black music without the writers and performers. Vaudeville audiences at this time also loved it when white women sang risque or melancholy songs in the deep, belting style associated with the blues. One performer in that vein that readers might know is Sophie Tucker, “the last of the red hot mamas.”

Gertrude Hoffmann didn’t sing in this style, but she did perform in blackface when she was imitating comedians who did the same. More frequently, she borrowed from what she perceived to be exotic cultures of the Middle East and East Asia, especially any stories originating in 1,001 Arabian Nights. That was definitely the case in modern dance too, where Ruth St. Denis gave her aesthetic interpretations of Indian dance.

What can we understand about New York City in the first third of the 20th century by looking at the career of Gertrude Hoffmann?

Her career is a great example of just how fluid the borders of popular performance were in pre-World War II New York City. So many of the Russian immigrants who were trained ballet dancers and choreographers moved regularly between concert dance and popular performance. That people who danced at the Metropolitan Opera probably performed in a Broadway musical comedy or a revue at the Hippodrome too. And in the same way that the boundaries between high and low culture were permeable, the history of different live entertainment forms was too. Her career shows that vaudeville hung on as a part of New York City entertainment for a really long time, both in nightclubs and in the mix of live performance and film at places like Radio City Music Hall and smaller theaters in the outer boroughs.

Sunny Stalter-Pace is the Hargis Associate Professor of American Literature at Auburn University. She is also the author of Underground Movements: Modern Culture on the New York City Subway.