From the CUNY Digital History Archive: The Five Demands and the University of Harlem

By Chloe Smolarski

The CUNY Digital History Archive, founded in 2014, collects and makes available primary source documents that address the history of the City University of New York, the system of public colleges that serves New York City. Many of the collections date from the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time of radical ferment at CUNY. Following a historic wave of student protest, the university embarked upon a radical experiment that offered low-cost public higher education to all graduates of city high schools. In the piece that follows, CDHA Program and Collections Coordinator Chloe Smolarski highlights and contextualizes some key documents from the struggle of Black and Puerto Rican students at City College to build a university that responded to the needs of their communities. This year marks the fifty-year anniversary of those struggles. –Ed.

In 1847, the president of the Free Academy of New York defined the mission of the school that would become CUNY as an experiment to determine “whether the children of the people, the children of the whole people, can be educated; and whether an institution of learning of the highest grade can be successfully controlled by the popular will, not by the privileged few, but by the privileged many.” Over the next 150 years, students, faculty, and staff have struggled to ensure that CUNY has lived up to this mission.

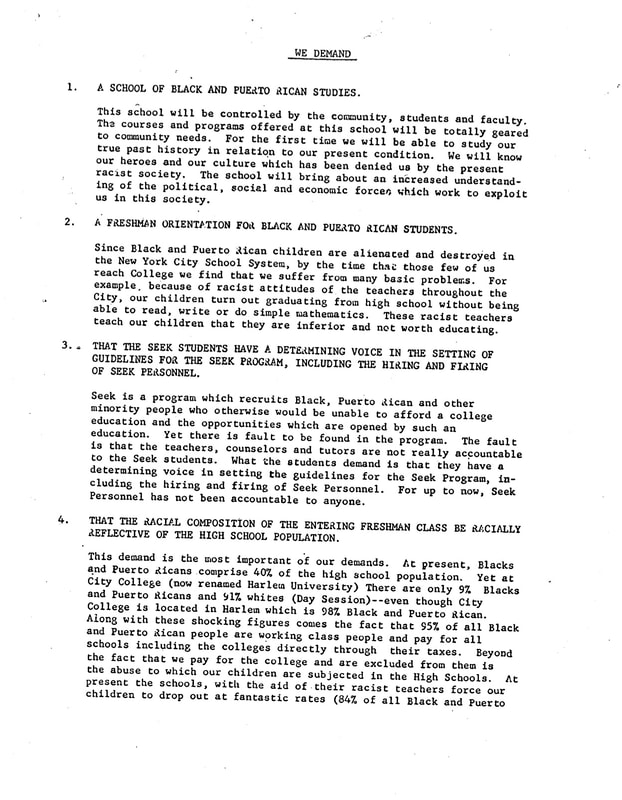

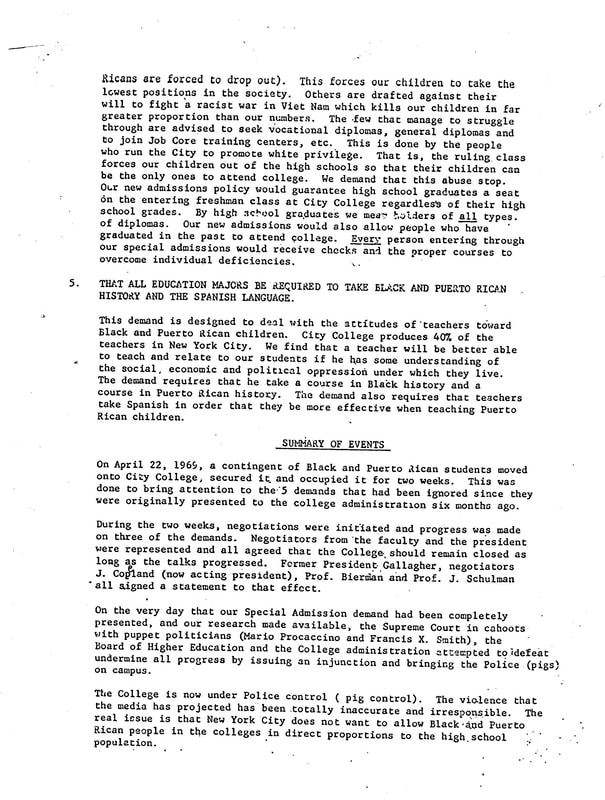

This typewritten handout, created by a group of protesting City College students in April 1969, is one of the many primary documents in the CUNY Digital History Archive (CDHA) that records the history of student activism at the City University. CDHA gives the CUNY community and the broader public online access to a range of materials that will inform the study of public higher education in New York City. CDHA accepts materials from individuals whose lives, in diverse ways, have shaped and been shaped by CUNY.

In the spring of 1969, as the ideals of the civil rights movement coalesced with global liberation struggles, the injustice of a primarily white school, located in the heart of Harlem but not adequately serving the community’s interests, was not lost on an increasingly radicalized student body.

In 1969, forty percent of New York City high school students were black or Puerto Rican. But City College, the jewel of the City University system, remained ninety-one percent white. Black and Puerto Rican students fought for greater representation in the faculty, the student body, and the curriculum. The “Five Demands” they issued in late 1968—and the series of militant protests that backed them—ultimately helped pave the way for CUNY’s Open Admissions policy, which guaranteed a seat at a CUNY school for all graduates of city high schools. The fourth demand—the “most important,” according to protestors—called for an inclusive admissions policy at City College that would ensure the student body accurately reflected the demographics of New York City. “Our new admissions policy would guarantee high school graduates a seat on the entering freshman class at City College regardless of their high school grades,” the protestors wrote.

From April 22, 1969 through the end of the semester, students at City College organized protests, strikes and more. Steadfast in their demands, the students from the Black and Puerto Rican Student Community (BPRSC) occupied campus buildings, which they renamed the University of Harlem. A press release from the BPRSC describes the occupation, during which students sought to feed, shelter, and educate local residents. Shortly after the initial takeover, a group of white students occupied Klapper Hall in solidarity with the BPRSC, renaming it the Huey P. Newton Hall for Political Action in honor of the Black Panther Party co-founder.

As this flyer indicates, police used physical violence to dislodge the protestors. There were also significant conflicts among the students themselves. Nonetheless, their actions led the Board of Higher Education to implement its Open Admissions policy just a few months later. The result—access to low-cost public higher education—would radically transform both CUNY and New York City itself.

Chloe Smolarski is the Program and Collections Coordinator at the CUNY Digital History Archive. She is a media maker, artist, and educator, and has studied and worked at CUNY for more than ten years.

Special thanks to Ron McGuire for contributing many of the primary documents included in this post.