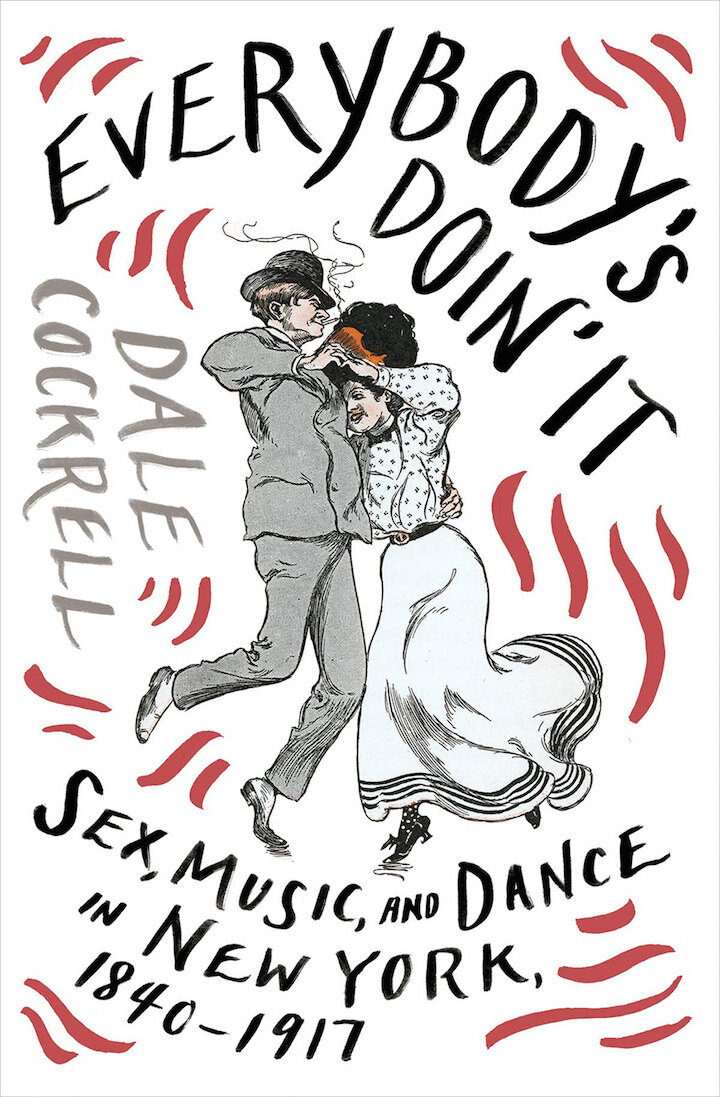

Everybody’s Doin’ It: Sex, Music and Dance in New York, 1840-1917

Reviewed by Jeffrey Escoffier

Everybody’s Doin’ It: Sex, Music and Dance in New York, 1840-1917

By Dale Cockrell

W.W. Norton & Co., 2019

288 Pages

Dirty Dancing, the 1987 movie starring Patrick Swayze and Jennifer Grey, exploited a common cultural trope: the intimate connection many people feel between dancing and sex. It portrayed a couple whose dancing was explicitly sexual, who came from different social classes and who at the same time were falling in love. For many of its viewers, it presented a very romantic vision of the connection between sex and dancing. Dale Cockrell’s Everybody’s Doin’ It: Sex, Music and Dance in New York, 1840-1917 (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 2019) sets out to explore a more historical account of the interrelationship between popular music, social dancing and sexuality in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America. As he shows, the making of popular music during the nineteenth-century often took place in bars, brothels and dance halls where prostitution was endemic. Social dancing was one of the ways that sex and music are linked.

In the course of doing that, Cockrell touches on important overarching themes dealing with race, class, popular culture and sexuality. In fact, Cockrell provides evidence for three broader theses: (a) the centrality of African and African-American musical culture in the development of popular music in nineteenth-century America, (b) that the sexual attitudes and behavior of working-class Americans during the nineteenth-century (both for good and for ill) exhibited little of the Puritanism or repressiveness that is often attributed to it by present-day commentators, (c) and that the anti-vice crusaders of the late nineteenth-century, such as Anthony Comstock, the Rev. Charles Parkhurst, as well as the citizens who started the urban Anti-Vice Commissions of the early twentieth-century, specifically targeted those gathering places (bars, saloons, and dance halls) that facilitated inter-racial social mixing, which they believed to be inherently a form of vice.

The popularity of blackface minstrel shows set the stage for the emergence of a music that mingled African American and European (Irish especially) music and dancing and that eventually led to ragtime and jazz. Despite the racism and the caricature of blacks and their culture under slavery, blackface minstrel music was where the influence of African musical culture was first evident. Everybody’s Doin’ It is a follow-up from Cockrell’s previous book, Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World, which was the first study of blackface minstrelsy by a musicologist.

When Charles Dickens visited the United States in 1842, he visited several bars in the Five Points area of Manhattan (east of today’s Centre Street & just north of Worth Street), a neighborhood which at the time had both large black and Irish populations—tap dancing was said to have been invented in Five Points by combining Irish step-dancing with African rhythmic patterns. In American Notes, Dickens’ book about his visit to the U.S., he wrote about his visit to several bars in Five Points. In one bar, he observed two black musicians, playing a fiddle and a tambourine, performing for a mixed group of blacks and whites. But he focused especially on the virtuoso performance of William Henry Lane, a young black dancer, who went by the name of Juba:

“Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross-cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like … the man’s fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs—all sorts of legs—what is this to him?”

Another account of musical life in Five Points at that time, by journalist George Goodrich Foster gives an even more vivid picture of the musical and sexual atmosphere:

“The room looks large, a large dimly-lighted cavern. On a barrel by the side of the bar sits an old negro, tuning his fiddle, while the dancers on the floor have just taken their places. Away they go — a fat and shiny blackamore with arm around the waist of a slight young girl, who skin is yet white and fair, but whose painted cheeks and hollow glaring eyes tell how rapidly goes on the work of disease and death. Opposite this couple, a man as naked as the first moment of his birth, whirls shouting and yelling away with a brutal-looking woman, once evidently a queenly beauty… Around the sides of the room in bunks, or sitting upon wooden benches, the remainder of the company wait impatiently their turn on the floor—meanwhile drinking and telling obscene anecdotes or singing fragments of ribald songs.”

These two anecdotes from the 1840s illustrate the interaction of musical exuberance and dancing in the sexual context.

However, toward the end of the nineteenth-century, racial intermixing and popular music were increasingly seen as dangerous and immoral influences. Reformers like Anthony Comstock and the Reverend Charles Parkhurst launched campaigns to stamp out everything from drinking on Sundays, pornography, contraception, abortion and prostitution, including as well ‘wild music’ and ‘lascivious dancing.’

The emergence of ragtime in the 1890s provoked an especially strong reaction. To some degree, these anti-vice crusades coincided with the emergence of ragtime as a new musical and dance form. Composed by black musicians, to be played in saloons, bars, brothels and cafes it was rarely written down but it is the first identifiable style of jazz. Early jazz musicians such as Jelly Roll Morton, Eubie Blake, and James P. Johnson were often employed to play in the brothels in Storyville, New Orleans’s fabled red light district. There and in the sex districts of many other cities —many of which were located in or near African American neighborhoods — both musicians and dancers found niches and a degree of acceptance.

Before ragtime, there had been an emphasis on learning complicated steps. But with ragtime, the main impetus of social dancing was the music’s rhythm and the impulse that it gave to dancing. The one-step, called so because one-step was taken to each beat of the music with a constant tempo, was the first kind of dancing done to ragtime. The one-step was much simpler than many earlier forms of social dancing, such as the waltz or the polka, and it undercut the social distinction to be gained by ballroom dancing lessons. Anyone could learn the steps by observation in an evening of dancing. One English observer noted,that “all you have to do is grab hold of the nearest lady, grasp her very tightly, push her shoulders down a bit, and then wiggle about as much like a slippery slush as you possibly can.” The one-step spawned a series of other dances accompanied by different arm and body gestures: the turkey-trot involved flapping one’s arms like a turkey, the grizzly bear included lurching like a bear, and so on with the bunny hug, the shiver, and the Boston dip. These were all considered forms of “tough dancing.” Since many of the newer versions of the one step allowed much closer physical contact between the couple, in part, because they were somewhat slower than the waltz or the polka, these new dances were considered immoral.

Tough dancing — which might be considered an early twentieth-century term for dirty dancing—provoked Comstock, Parkhurst and the anti-vice campaigns launched by private citizens—known as the Committee of Fifteen (1900-01) and the Committee of Fourteen (1906-1912)—to wage war on the bars, dance halls, and other places were popular music was played and dancing took place. Many of these places were multi-racial venues, known also as “black and tans” which the vice crusaders considered by definition to be examples of the worst debauchery. The Committees’ campaigns devastated the City’s nightlife and undermined many of its musical entertainment venues. They especially targeted black-run and patronized hotels, clubs, and cafes, thus seeking to establish a racial divide and enforce a division between the races.

Cockrell also illustrates how the ‘Victorianism” of nineteenth-century American attitudes towards sexuality was a thin veneer propagated by upper-class elites and religious conservatives over the rougher attitudes of young working women and men. In addition to Everybody’s Doin’ It’s valuable contribution to the history of popular music and dance, it integrates that history into the history of working class culture and sexuality in New York City as well, thus extending the work of Luc Sante’s Low Life: the Lures and Snares of Old New York and the work of such scholars as Christine Stansell, City of Women: Sex and Class in New York, 1780-1860; Timothy Gilfoyle, City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution and the commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920; Elizabeth Alice Clement, Love for Sale: Courting, Treating, and Prostitution in New York City, 1900-1945; Patricia Cline Cohen, Timothy Gilfoyle and Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, The Flash Press: Sporting Male Weeklies in 1840s New York; Chad Heap, Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885-1940. But like musicologist Ned Sublette’s history of New Orleans (The World That Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square), Cockrell uses the music and popular dance forms to narrate the social history of the city. Thus, what on the surface may appear to be a modest historical study of popular music and dance has identified the deep connection between explicit attacks on popular music and interracial socializing by the anti-vice crusaders of the late nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century.

Jeffrey Escoffier has written on dance and on the history of sexuality. He is on the faculty of the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research.