The Art of Blackwell's Island

By Kristen Osborne-Bartucca

Figure 1. Julius Golz, The River, 1906, Oil on canvas, Delaware Art Museum.

American impressionist Julius Golz usually painted the New Jersey shoreline and countryside, but in 1906 he turned to the small strip of land in the middle of the East River known as Blackwell’s Island. Featuring the island on a wintry day from the perspective of someone standing on the opposite shore, The River (1906) was much bleaker in palette and gloomier in mood than most of Golz’s works (Figure 1). Robert Henri, leader of the Ashcan School of painting in New York at the turn of the 19th century, praised the work of his student, marveling, “Take the picture, for instance, of Julius Golz, the painter of Blackwell's Island and the East River. What force and power is in this man's work. He seems to be the only man who has ever painted the East River, that wonderful snowswept fence against that absolutely deep and tragic water and then beyond, Blackwell's Island, and all done without a particle of sentimentality.” [1]

Golz may have been interested primarily in the river and the weather, but his choice to include Blackwell’s in his disquieting scene prompts a consideration of what the island, by then an infamous site of failed institutional reform, meant to artists. Certainly journalists, politicians, and reformers had their eyes on Blackwell’s during its time of operation, but several of New York’s artists also saw Blackwell’s as a site of interest — some for aesthetic reasons, others for social, and many for both.

Following a brief introduction to Blackwell’s Island and its institutions, this article will discuss the paintings featuring the island, which range from bucolic scenes that seemingly elide any social concerns to disturbing ones that offer, sometimes obliquely and sometimes explicitly, a referendum on the horrors that happened there.

Antebellum Reform and Blackwell’s Island

In 1843, reformer Dorothea Dix lamented the inhumane treatment of “helpless, forgotten, insane, and idiotic men and women; of beings sunk to a condition from which the most unconcerned would start with real horror; of beings wretched in our prisons, and more wretched in our almshouses.” [2] Being housed in jails without the opportunity to work, she claimed, exacerbated inmates’ mental decay; instead, the insane should be placed in “good asylums” and have employment, which would contribute to their mental health and maybe even help them recover. [3]

Dix was one voice among many in terms of advocates for the insane, indebted, and criminal. Part of a larger wave of social reforms and religious revivals in the first half of the 19th century, institutional reform focused on separating these people from the general population but treating them in a manner characterized by much more humanity than in the past. It was endorsed by politicians and elites worried about their (supposedly) deteriorating cities, doctors studying mental health, and reformers and religious leaders concerned about marginalized, suffering populations.

In New York City, Bellevue Hospital had been treating the sick as early as 1798, but by the mid-19th century it was acting not only as a hospital for the poor but also as the city’s penitentiary, almshouse, asylum, and workhouse — exactly the sort of chaotic institution reformers decried. City officials concluded that they needed new structures for each of these purposes, and, per prevailing theories, inmates ought to be isolated from the general population.

Blackwell’s Island, situated in the middle of the East River, seemed to be the ideal place to put the people the city wanted to reform — or simply forget about. Originally called Minnehanonck by the Lenape, the island was purchased by the Dutch and then ceded to the British after their victory in 1664. For a time it was occupied by a British military captain, John Manning, who later bequeathed it to his stepdaughter, Mary. Mary wed Robert Blackwell, and that family settled on the island for several generations before selling it to the city of New York in 1828.

Two miles long, with thick woods and stone quarries that provided building materials, Blackwell’s was close enough for the city (only a few hundred feet away at the island’s widest points) to transport people and supplies while also maintaining a separation. With a plan and a site in place, the city moved quickly. The penitentiary (for people convicted of serious crimes) opened in 1832, the Lunatic Asylum in 1839, the almshouse in 1848, the workhouse (for people convicted of minor crimes) in 1852, the Smallpox Hospital in 1856, and City Hospital in 1859. Many 19th century architects, doctors, social reformers, and urban planners were convinced that environment shaped a person’s conduct and, in the case of the insane, could even facilitate a cure, so the edifices were designed and constructed with care. [4] Several of Blackwell’s buildings were even designed by famous architects, and, in their classically beautiful and imposing facades, were meant to be visual manifestations of what the city considered its serious and noble endeavor of taking care of society’s less fortunate.

Despite the beautiful buildings and lofty goals, however, every single one of the institutions on Blackwell’s became notorious for their extreme disregard of the people under their care. Overcrowding and cut budgets were part of the problem, but deeply rooted biases regarding class, race, and ethnicity took their toll as well. [5] The poor were treated miserably, subject to the deeply rooted conflation of poverty with immorality and criminality. The penitentiary was considered “a disgrace to the city of New York,” its cells filthy and crowded, the incarcerated subject to violence, illness, and despair. [6] Of the penitentiary hospital, a New York Times reporter called it a “horrible moral ulcer” and shuddered, “I defy the stoutest-heartest layman to go through the wards of this hospital without fairly growing sick at the stomach.” [7]

The Asylum failed in its idealistic aims almost immediately. It was overcrowded, unsanitary, and the inmates were treated cruelly. In a direct violation of reformers’ plans to separate people by condition, inmates from the penitentiary were often brought in to act as guards at the asylum. In his 1842 visit for American Notes, Charles Dickens proclaimed that “I never felt such disgust and measureless contempt as when I crossed the threshold of this madhouse.” [8] The general population had some suspicions about the Asylum, passed along from inmates and some visitors like Dickens, but most of the time the actual conditions were hidden from visitors, who tended to be wealthy women whose financial support the institutions coveted. [9] In 1887 that changed, however, when young reporter Nelly Bly went undercover by pretending to be, as her admission stated, “positively demented.” [10] She published a searing expose of the facility in New York World, writing of the physical discomfort, the terrible food, and the abusive treatment on the part of nurses, concluding that even the sanest of women only needed two months here to “make her a mental and physical wreck.” [11]

Thanks to Bly’s investigation in particular, the failures of Blackwell’s Island became well-known across the country. [12] Some asylum inhabitants had already been moved to Ward’s Island at the time of Bly’s piece, and now the city began moving patients to other hospitals. In 1921 the city renamed the island “Welfare Island,” but as the 20th century progressed, all of its facilities were eventually abandoned and fell into ruin. In 1973, the city named the island yet again, this time for Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and began transitioning it to a master-planned, middle-class community.

The Art of the Island

The works considered here are almost all paintings. With the exception of Ben Shahn, who photographed the inmates of Blackwell’s Island Penitentiary in 1934 as a study for a mural he was painting at Rikers’ Island, the city’s new prison site, the documentary photographers of the early-mid 20th century did not seem to have made Blackwell’s a subject. And, again with Shahn as the exception, none of the artists during Blackwell’s days of operation actually created their works on the island or even tried to imaginatively depict what the interior of the island looked like. Rather, they are all from the perspective of someone on the river itself or on its Manhattan side — all of which makes sense given the fact that opportunities to visit the institutions were limited.

Figure 2. Frederic Edwin Church, View of Blackwell's Island, New York (Youle's Shot Tower, East River, New York; View of Hartford), 1850, oil on canvas, location unknown.

Especially in the mid-19th century, Blackwell’s natural beauty was hard to ignore. In his 1850 work View of Blackwell's Island, New York (Youle's Shot Tower, East River, New York; View of Hartford), Frederic Edwin Church, one of the most famous painters of the Hudson River School, situated his viewer on the Manhattan shore, looking across the windswept river with sailboats and steamships to Blackwell’s (Figure 2). This is one of the earliest artistic depictions of the island and only some of the buildings are constructed, their size diminutive and their purpose inscrutable, and much of the island still lushly wooded. Church’s focus is primarily on the Manhattan foreground with its lambent green lawns, sleeping cows, and Youle’s tower (for manufacturing lead ammunition). It is an idyllic, pastoral scene complete with a rainbow in the sky after a passing shower.

Similar to Church’s work, Louis Grube’s 1857 painting East River and Blackwell’s Island, New York City, which was commissioned by the wealthy Beekman family, is almost misleading in its title, as the river and island are only barely visible from the expansive Beekman residence in the foreground. There is no hint of what went on over at Blackwell’s; for this influential family, it was simply part of their scenery.

Scottish-born and largely self-taught artist Andrew Melrose’s 1890 painting The Work House of Blackwell’s Island (c. 1890) explicitly identifies one of the island’s buildings, but it is painted from the river at a comfortable distance and, like Church’s work, is bright and almost cheery. A white steamboat and a small boat with passengers carrying colorful parasols approach the elegant edifices on the shore, and while the wind seems bracing, the bright blue sky and puffy, rolling clouds give no hint of anything sinister. It appears to be more of a scene of leisure that happens to be taking place on the part of the East River near the island than any sort of social commentary.

Figure 3. Robert Henri, Blackwell’s Island, East River, 1900, oil on canvas, Whitney Museum of American Art.

Even though it contains the same basic pictorial elements of sky, river, and island, Robert Henri’s painting, Blackwell’s Island, East River (1900) could not be more different from the prior works (Figure 3). By 1900, Bly’s expose had been published, and it is not too farfetched to imagine that many New Yorkers, especially socially-conscious artists, were aware of the failures of the island’s institutions. Like all the artists grouped under the term “Ashcan School,” a once-pejorative label from a critic that later was embraced by the artists themselves, Henri refused to sugarcoat the gritty urban environs in which he lived and worked. His studio on 58th street on the edge of Manhattan overlooked Blackwell’s Island, and in his several renditions of it he alluded to its seamier side. This version consists of a dingy, oily sky and a flat, gray river choked with ice. The tip of Blackwell’s juts out into the river, consisting of several buildings densely packed together, their roofs heavily laden with snow and puffs of smoke feebly rising into the sky. It is an unsettling image that cannot help but make one think of the poor souls shivering inside the walls.

Figure 4. George Bellows, The Bridge, 1909, oil on canvas, Toledo Museum of Art.

Blackwell’s is featured in fellow Ashcan artist George Bellows’ 1909 work The Bridge, but while the artist often embedded social commentary in his paintings of urban life, he did not choose to do so here (Figure 4). Instead, Bellows focused on one of his other aesthetic passions — the infrastructure of the modern city. The titular bridge is the Queensboro Bridge, painted the year it was completed, and Blackwell’s Island is more or less incidental to the composition. It is there underneath the heavy span of the bridge, but it is just a short visual stop as the viewer’s eye moves over to the dense shores of Queens.

Figure 5. Edward Hopper, Blackwell’s Island, 1911, oil on canvas, Whitney Museum of American Art.

Edward Hopper also painted the new bridge and Blackwell’s Island. Blackwell’s Island (1911), the first of Hopper’s two works on the subject, is from the perspective of someone on the bridge at twilight, looking across the moon-dappled river to the island (Figure 5). Hopper renders the buildings almost abstractly, using thick brushstrokes to meld them dreamily into the landscape. It is a silent, serene scene, and while the island does not feel as incidental as it does to Bellows’ work, this early Hopper painting is likely meant to be a meditation on the city’s crepuscular beauty, not a nod to the island’s reputation.

Hopper’s second work depicting the island, Blackwell’s Island (1928), is stark and unsettling, related mostly in title to the 1911 piece. This work is similar to Hopper’s mid-career paintings such as Automat (1927), Night Windows (1928), Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928), Early Sunday Morning (1930), and Shakespeare at Dusk (1935), all of which depicted the spaces and inhabitants of the city with a “brooding, faintly sinister stillness,” as one critic for the New York Herald Tribune stated. [13] The river, a bright cerulean blue, occupies the bottom half of the canvas, and the top half consists of pale blue sky and odd clouds receding into the distance. All of the infamous institutions on the island are there, but by now had almost ceased operating. Hopper paints them as flattened, simplified, and lit brilliantly by the sun. Like most of his works, there is something slightly off about the scene — it is too quiet, too placid. Though the buildings are banal, Hopper suggests that there is something ominous that occurred within their walls.

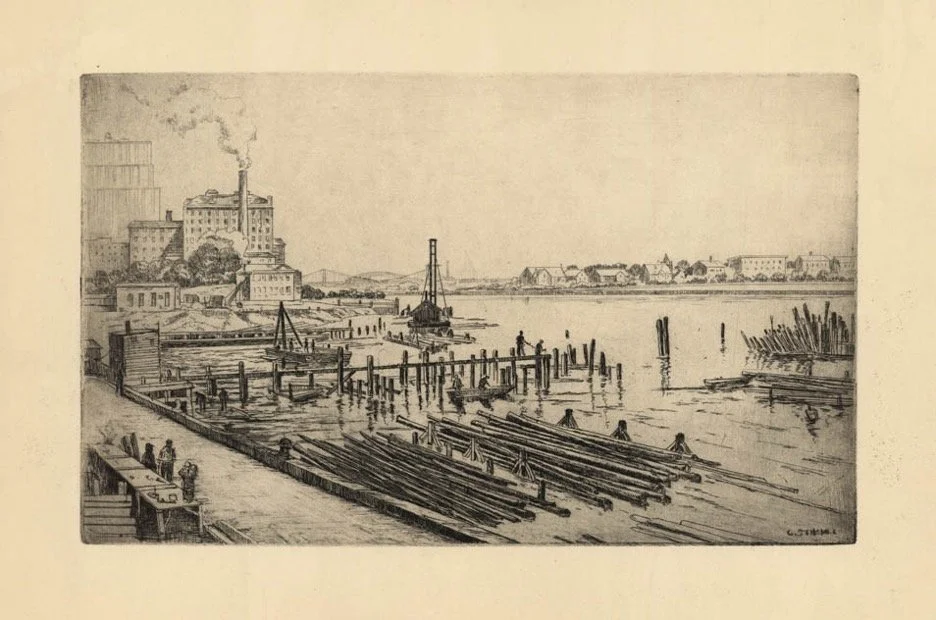

Figure 6. George Stimmel, Welfare Island, NY, c. 1940, etching, The Old Print Shop.

Approaching the midpoint of the 20th century, Blackwell’s institutional days were fading more and more into the past. But the buildings were still there, and artists continued to depict them. Some did so in a utilitarian fashion, like in George Stimmel’s circa 1940 etching, Welfare Island, NY, which backgrounds the island to the extent that it is barely visible (Figure 6). Instead, the viewer focuses on the busy docks in the foreground, seeing the island’s buildings as simply part of the infrastructure of a modern city. Gershon Benjamin also does this in Looking Toward Roosevelt Island (n.d.), in which the island, its buildings unremarkable shades of brown and beige, is pushed to the back of the picture plane in favor of large swathes of cool blue sky and river, which provide the real visual interest.

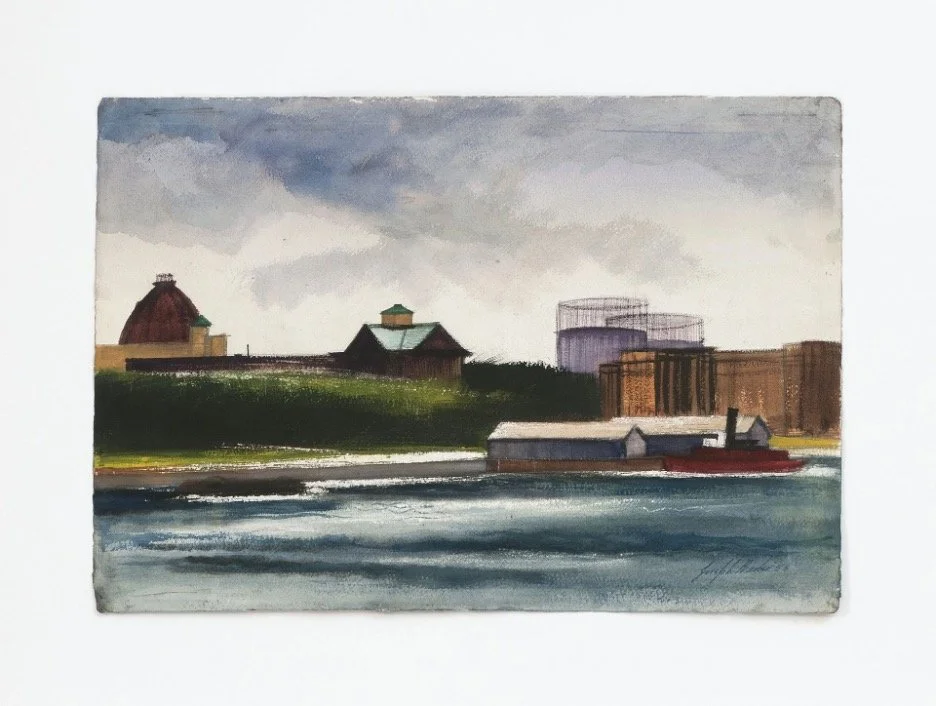

Figure 7. Joseph Barber, Welfare Island NY, n.d., watercolor on paper, private collection.

Yet others continued to imbue their paintings of Blackwell’s with something haunting. Joseph Barber’s early 20th century watercolor, Welfare Island NY (n.d.) uses shades of dark brown for several of the island’s decommissioned buildings, simplified and distanced from the viewer, and frames them with a slate-gray river and sky (Figure 7). Not a single living creature populates the work, but there is a distinct carceral tone to it, a sense that here on this island people were held and punished.

Figure 8. Ferdinand Lo Pinto, View from the Welfare Island, 1940, oil on canvas, overall: 24 x 30 in. ( 61 x 76.2 cm), gift of the Federal Works Agency, Works Projects Administration, the New York Historical.

Ferdinand Lo Pinto’s View from the Welfare Island (1940) visually equates the lighthouse on the right (the erstwhile entrance into the Lunatic Asylum) with steam of the ship on the left, both rendered in a rusty brown color in order to suggest something dirty (Figure 8). Though abandoned by 1940, the sepulchral structure still connotes surveillance and control.

Figure 9. George Picken, The Octagon, c. 1940, oil on canvas, private collection of the Igleheart Foundation, courtesy Lincoln Glenn Gallery.

And then there is George Picken’s The Octagon (c. 1940), perhaps the most disturbing work depicting Blackwell’s Island (Figure 9). It is a grim image featuring the black river; a dark, cloudy sky with an eerie glow; the ruins of the lighthouse; and several buildings, most of which, including the titular octagon, are devoid of any light except for one that has every single window garishly lit as in some parody of warmth and comfort. By 1940 the Asylum was no longer functioning, making Picken’s suggestion of life within all the more haunting.

Coda: Beyond Blackwell’s

Figure 10. Gil Ortiz, Welfare Island, 1971, digital pigment print, private collection.

In the mid-late 20th century, as Blackwell’s buildings came down, middle-class New Yorkers moved in, and the city prepared to name the island for the third time, painters no longer made Blackwell’s the subject of their work.

We can end, then, not with a painting but with a photograph from 1971–Gil Ortiz’s Welfare Island (Figure 10). By focusing on the ruins of the buildings, Ortiz creates a deeply elegiac, mournful mood. The windows are either shuttered or shattered, the foliage ripped out or overgrown. There isn’t a single person to be seen, but the photograph acts as a trace of this site where so many suffered. The most poignant part of the image is the white outline of a heart some contemporary visitor had drawn on the side of one of the buildings; it reminds one of Roland Barthes’s punctum, or the “wounding” element of a photograph. It is impossible not to contemplate those lives lost, locked away, and forgotten on the island over the years.

Kristen Osborne-Bartucca is an educator and arts writer who focuses on the history and art of New York City. She holds an MA in American Studies from Columbia University and a BA in History from the University of California, Riverside. Her most recent publication is “Jane Freilicher’s Windows” Mutual Art magazine, August 2025, and she runs an instagram account, @newyorkarthistory.

[1] “The River,” Delaware Museum of Art. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://emuseum.delart.org/objects/1433/the-river?ctx=4a8b168584645e3cc65d618d81fa5c3240af0182&idx=0.

[2] Dorothea Dix, Memorial. To the legislature of Massachusetts [In behalf of the pauper insane and idiots in jails and poorhouses throughout the Commonwealth. Jan. 1843]. National Library of Medicine. Accessed July 7, 2025. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101174442-bk.

[3] Dorothea Dix, Memorial soliciting a state hospital for the insane, 1845. Library of Congress. Accessed July 7, 2025. https://www.loc.gov/item/08015608/.

[4] Yanni, C. (2003). The Linear Plan for Insane Asylums in the United States before 1866. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 62(1), 24–49. Accessed August 1, 2025.

[5] Grob, G. N. (1973). Class, Ethnicity, and Race in American Mental Hospitals, 1830–75. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 28(3), 207–229. Accessed August 1, 2025.

[6] “PRISON HOSPITAL SEEN AS PEST HOUSE; Commissioners Say Diseased, Criminal and Voluntary Patients Mingle in Blackwell Cells. HELD HOURS IN FILTHY DEN Lack of Matrons Prevents Exercise --Get No Schooling--Four Changes Urged,” New York Times, January 21, 1921. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/1921/01/19/archives/prison-hospital-seen-as-pest-house-commissioners-say-diseased.html.

[7] “SKETCHES FROM THE LIFE SCHOOL-II,” New York Times, September 24, 1852. Accessed July 7, 2025. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1852/09/24/87842285.html?pageNumber=3.

[8] Charles Dickens, American Notes for General Circulation, 1842. Project Gutenberg. Accessed July 7, 2025. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/675/675-h/675-h.htm.

[9] Stacy Horn, Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad & Criminal in 19th Century New York (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2018).

[10] Nelly Bly, Ten Days in a Mad House, 1887. Digital Library of the University of Pennsylvania. Accessed July 7, 2025. https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/bly/madhouse/madhouse.html.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Horn, p. 84

[13] R. Cortissoz, "Examples of French and American Art: Two Americans," The New York Herald Tribune, January 27, 1929. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5683318.