Alice Neel: A Painter of Her Time

Reviewed by Jeffrey Escoffier

Alice Neel believed that “art is a form of history.” Born in 1900, she claimed that “I represent the 20th century… I’ve tried to capture the zeitgeist.” Yet her painting bore no resemblance to the vast canvases of iconic scenes from the French revolution by Jacques-Louis David, Anne-Louis Girodot, or Theodore Gericault. Instead, she portrayed the history of the 20th century through individual people — neighbors, friends, artists, celebrities, and political activists — that she knew in New York City, a city which might be considered the capital of the 20th-century — the successor to Paris as “the capital of the 19th-century.”

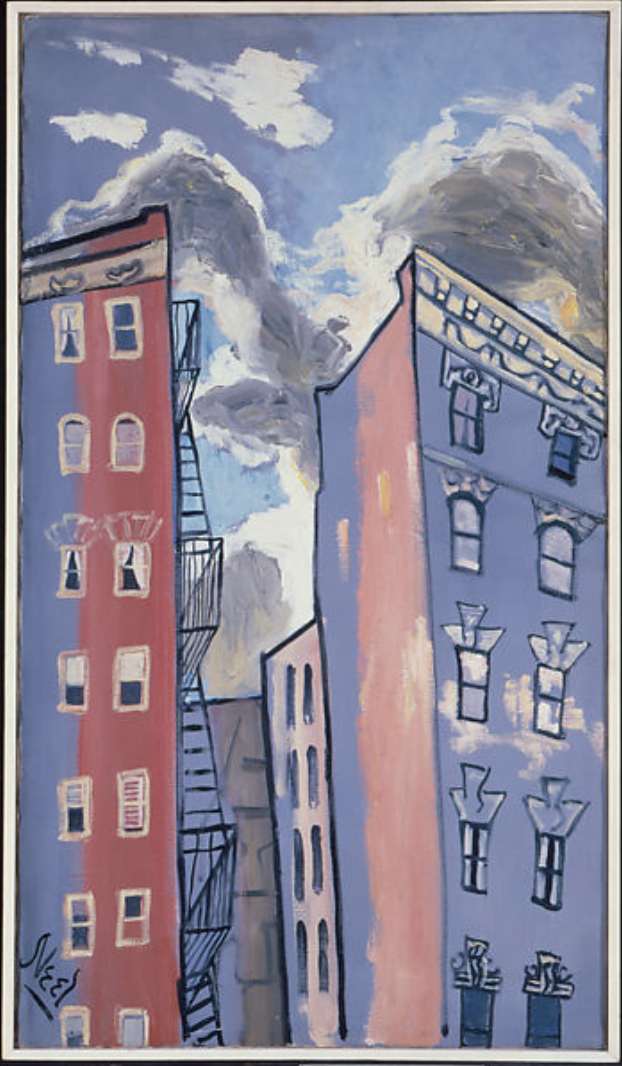

Sunset in Spanish Harlem, 1958. Estate of Alice Neel

The exhibit of Neel’s work currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a sweeping survey of her work — more than 100 paintings, drawings and watercolors — from the 1920s up until her death in 1984. Considered one of the greatest portrait painters of the 20th century, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith has even argued that Neel was equal, if not superior to, artists such as Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon.

Alice Neel was born in Merion Square, Pennsylvania and attended the Philadelphia School of Design (now the Moore College of Art and Design). In 1925, she married Cuban painter Carlos Enriquez and moved with him to Havana, where she participated in the avant-garde art scene there. In 1927, Neel and her husband moved back to New York. They separated in 1930 and Enriquez moved back to Cuba, taking their daughter with him. She saw her daughter only twice during her lifetime after that, and never saw her husband again. In the wake of that devasting loss she suffered a nervous breakdown, was hospitalized, and attempted suicide. In 1931, after spending some time in a psychiatric hospital, Neel returned to New York and settled in Greenwich Village. She became one of the first artists to work for the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal program designed to provide jobs during the Depression. She also joined the Communist Party, and during that period she painted portraits of many Communist Party leaders, intellectuals, political activists and fellow artists in addition to street scenes and still lifes.

Modern American art from the mid-thirties on developed within a broader debate partly shaped by the economic and political situation in the United States. The Ashcan School of American painters (Robert Henri, John Sloan), who focused on daily life and urban poverty, was an early influence on Neel. In the 1930s many artists on the Left painted realist representations of the victims of capitalism — the working class, displaced farmers, and the poor — caught up in the economic devastation of the Great Depression. The Communist Party promoted the realist perspective as the only legitimate aesthetic for the Left, under the presumption that “socialist realism” documented the true impact of capitalism on everyday life.

For Neel, art was not only history, it was also politics. As the main character in art critic John Berger’s great novel, A Painter of Our Time proclaimed:

There are three ways in which an artist can fight for what he believes:

(1) With a gun or stone…

(2) By putting his skill at the service of the immediate propagandists…

(3) By producing works entirely of his own volition… in which the no-less-strong force he works under is his own inner tension.[1]

Neel chose the third path, though close to the realist end of the spectrum, while other American artists in the 1930s, such as Alexander Calder, Roberto Matta, and Yves Tanguy, some of them leftists as well, explored varieties of abstraction. After World War II, with the dominance of abstract expressionism, the center of modernist painting shifted from Paris to New York and Neel’s “expressionist realism” was dismissed as old-fashioned. Despite her long affiliation with the Communist Party, Neel did not follow the party’s guidelines. “I hate obvious political paintings,” she said, “because they’re stereotyped and boring.” Neel’s painting was much more in the style of the leftwing expressionist painters of Weimar Germany such as Max Beckmann, George Grosz, and Otto Dix. Neel claimed that she “was never a good Communist;” instead, she always insisted that “People Come First” which is the perfect title of the Met’s show.

By the 1930s, it was evident that New York City was Neel’s muse and most of her work was influenced by where she lived in the city. As she moved from Greenwich Village to Spanish Harlem and the Upper West Side she painted prolifically wherever she went — everything from street scenes and urban landscapes, as well as her friends, neighbors, pregnant mothers, political activists, children, artists and various celebrities, many times in the nude.

Dominican Boys on 108th Street, 1955. Estate of Alice Neel

Marxist Girl (Irene Peskilis), 1972. Estate of Alice Neel

During the early thirties, most of her work focused on the issues that grew out of her political commitment — as in Investigation of Poverty at the Russell Sage Foundation (1933), Synthesis of New York-The Great Depression (1933) and Longshoreman Returning from Work (1936), in addition to portraits of political activists and intellectuals. In 1938, Neel, along with her partner, musician Jose Santiago Negron, moved from Greenwich Village to Spanish Harlem, which ran roughly from E 96th Street in Manhattan up to the Harlem and East River, a predominately Puerto Rican neighborhood with an influx of Dominicans. For the next twenty years the East Harlem neighborhood was the focus for much of her painting. In a short poetic tribute, she wrote: “I love you Harlem / Your life your pregnant / Women, your relief lines / Outside the bank… What a treasure of goodness / And life shambles…” She was one of the first artists to portray life in Spanish Harlem. “As a single mother of two trying to make ends meet,” New Yorker writer Hilton Als observed, “she recognized the struggle on her neighbor’s faces.” Writers like Piri Thomas (Down These Mean Streets, 1967) and photographers (Bruce Davidson, Felipe Dante, Sophie Rivera and Hiram Maristany) soon followed in her footsteps. She painted street scenes (Building in Harlem, 1945), markets (Fish Market, 1947) and some of the many of the kids she met on the streets: Dominican Boys on 108th Street (1955), Georgie Arce No. 2 (1955), Two Puerto Rican Boys (1956) and Two Girls, Spanish Harlem (1959).

Mother and Child, c. 1962. Estate of Alice Neel

From the beginning there was a strong feminist current running through her work. She was always interested in the plasticity of the female body, from a 1934 nude of her six-year-old daughter, or mothers nursing or with their newborns, up until the powerful and unsparing nude portrait of herself at age 80. Her incredible series of paintings of pregnant women — some clothed, others nude — reflected her interest in motherhood and the relations between mothers and their children, as well as her experience as a single mother of two sons who had the trauma of losing two daughters, one to death in infancy and the other to lifelong separation — affecting portraits of a South Asian Mother and Child (1962), Nancy and Olivia (1967) Carman and Judy (1972), her daughter-in-law Nancy and the Twins (1971) and art critic Linda Nochlin and Daisy (1973).

Georgie Arce no. 2, 1955. Estate of Alice Neel.

The political upheavals of the 1960s and 70s — the civil rights movement, the revival of the Left, and second wave feminism — was accompanied by a revitalized cultural vanguard and a sexual revolution. Neel had moved to the Upper West Side and developed new connections to the art scene, the women’s movement, and the queer community. Starting in the 1970s, she made a series of portraits of women who were feminists and political activists such as Kate Millett (1970), Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis) (1972), Adrienne Rich (1973) and Faith Ringgold (1977). As she garnered more recognition from the art world and had more social interaction with artists, she began to paint portraits of the people she encountered. In 1970, Neel painted Andy Warhol soon after Valerie Solanas’ assassination attempt, his thin naked chest crisscrossed with scars and wearing an abdominal support. In 1972, she made the delightful painting of art critic John Perreault lying nude on a narrow daybed. She also did a series of portraits of same-sex couples who were artists and writers: David Bourdon and Gregory Battcock (1970), Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd (1970), which depicts the Andy Warhol “Superstar” and their partner, and Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian (1978).

One of the great pleasures of this exhibit is the incredible range of “alive” people that Neel has brought to the show — conveyed to us by images ranging from powerful completely realized and polished paintings (Elenka, 1936), which is used as the cover image on the show’s catalogue to simple flat images dominated by a telling gesture or visual expression (Puerto Rico Libre!, 1939), or cartoon-like drawings (Untitled, (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom), 1935), and finally to beautiful suggestive impressionist-like paintings with empty spaces and dense detailed images (Black Draftee (James Hunter), 1965). Each room of the exhibit feels like a crowd, the people portrayed bounce off the walls.

Lucien Freud commented on how the difference between photography and painting is “the degree to which feelings can enter the transaction” between the artist and her subject. “Photography can do this to a tiny extent, painting to an unlimited degree.” Neel’s portraits demonstrate the huge degree of emotional interaction between the painter and her subject. This is evident not only in the way her subjects are seated — from a tense uncomfortable position on the edge of a chair to the relaxed way a couple sits naked on a couch, Neel’s portraits convey a powerful kinesthetic effect enhanced by her penetrating insight into her subjects. Her portraits are encounters inseparable from a certain degree of apprehension, encounters with people who are strangers yet also somehow familiar.

Alice Neel: People Come First is at The Metropolitan Museum of Art until August 1, 2021.

Jeffrey Escoffier writes on the history of sexuality, LGBTQ communities and New York City in the 1970s. He is the author of American Homo: Community and Perversity, recently reissued by Verso Books in its Radical Thinkers series. His Sex, Society and Making of Pornography was published by Rutgers University Press in February. He is currently a research associate and teaches at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research.

[1] (A Painter of Our Time, Vintage Books, 1996, p. 142