A Visit to Pfaff's

By Justin Martin

Take a walk along Broadway in Manhattan. As you make your way—amid the rushing taxis, pedestrians lost in their smartphones, and other scenes of modern bustle—you might just catch some hints of the distant past. Pause for a moment at 647 Broadway, a few doors north of Bleecker Street. A women’s shoe store is here, assorted boots, sandals, and stiletto heels displayed in the window. It appears to be just another shop along Broadway. But once upon a time, this was the location of the famous Pfaff’s saloon.

To be precise, Pfaff’s (pronounced fafs) was beneath where the shoe store is now. It was an underground saloon in every sense of the word. There’s still a hatchway in the Broadway sidewalk, just as there was in the 19th century. It provides entry into the store’s basement, a long, narrow space, lit by electric bulbs and piled high with boxes of shoes. During the 1850s, it was dim, gaslit, and packed with artists. Pfaff’s saloon was the site of an incredibly important cultural movement, the meeting place of America’s first Bohemians.

Their leader, Henry Clapp Jr., was editor of the hugely influential Saturday Press. Clapp deserves credit as the person who brought Bohemianism to America, both the word and the way of life. He was joined by a struggling experimental poet, well into middle age, yet still living at home in Brooklyn with his mother, Walt Whitman.

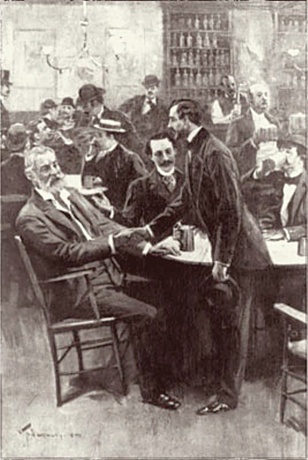

Around these two figures, a circle formed that included journalists, playwrights, sculptors, and painters. Among the mainstays were Artemus Ward, America’s first stand-up comedian, and the elegant writer Ada Clare (libertine Pfaff’s was the rare saloon that welcomed women in those days). There was also Fitz Hugh Ludlow, psychedelic pioneer and author of The Hasheesh Eater; Fitz-James O’Brien, a talented but dissolute writer; and actress Adah Isaacs Menken, wildly successful, unabashedly notorious, and one of the great sex symbols of the 19th century. By turns calculating and vulnerable, she was like a sepia-tone Marilyn Monroe.

On the eve of the Civil War, this motley group made the Broadway saloon its headquarters. The Pfaff’s Bohemians, as they were known, met here every night to drink, joke, argue, and drink some more. Along the

way, they also managed to create startling and original works. Although much of their output is long forgotten, its animating spirit lives on, continuing to have resonance today. The Pfaff’s Bohemians were part of the transition from art as a genteel profession to art as a soul-deep calling, centered on risk taking, honesty, and provocation. Everyone from Lady Gaga to George Carlin to Dave Eggers owes a debt to these originals. They were also the forerunners of such alternative artist groups as the Beats, Andy Warhol’s Factory, and the abstract expressionist painters who hung out during the 1950s at New York’s Cedar Tavern.

If you’ve never heard of Pfaff’s saloon, or its coterie of Bohemian artists, that’s not surprising. More than 150 years have elapsed since this scene’s heyday, and time moves in mysterious—sometimes heedless—ways. History is not a meritocracy.

Of course, Whitman has not been forgotten. But the importance of his participation in a circle of Bohemian artists has. This was no casual association. Between roughly 1858 and 1862, Whitman was at the saloon virtually every night.

Time spent among the Bohemians was crucial to the evolution of his masterpiece, Leaves of Grass. In 1860 he published a vastly expanded edition of the work, featuring more than one hundred new poems, many drawn from the experience of being part of this artists’ circle. The new edition even included an entire section devoted to romance between men. Pfaff’s—permissive place that it was—gave Whitman the opportunity to explore his sexuality in both art and life. Whitman’s barfly years were a vital stretch for him, filled with triumph and torment and intense creativity. It was that critical time before—before fame, before myth, before he had been forever fixed as the Good Gray Poet. Whitman himself recognized its importance. As an old man, he told Thomas Donaldson, one of his first biographers, “Pfaff’s ‘Bohemia’ was never reported, and more the sorrow.”

The outbreak of the Civil War scattered the Bohemians. Pfaff’s saloon opened up, loosing its colorful denizens into the world. Famously, Whitman went to Washington, DC, where he tended to wounded soldiers. Others saw battlefield action or traveled across the troubled nation performing theatrical pieces. A couple of the Bohemians even headed out to raucous silver-rush Nevada, where they met up with a promising young writer who only months earlier had adopted the pen name Mark Twain.

And then everything came crashing down. It’s almost as if the darkness surrounding Lincoln’s death couldn’t be contained, spread out, and infected the Pfaff’s set as well. These artists were intimately bound up with their times. Just like that, their times were at an end. Nearly everyone in the circle died young, often under grim circumstances. America’s first Bohemians burned brightly, but briefly, then flamed out in spectacular fashion. Whitman was among the few to live on, past that tempestuous era.

By the late 1860s, the group was fast receding into history. But memories of them remained vivid. For many years, it was a given that the famous Bohemian scene would be properly memorialized. “Pfaff’s, as it was, has passed away; but the history of it would make one of the most unique and startling books in American literature,” states an article in the Cincinnati Commercial from March 14, 1874. But the years kept slipping past, then decades . . . then entire centuries. One can easily walk along Broadway and go right past the shoe store, with no idea that Walt Whitman and a group of artists used to meet below in that basement saloon.

But it’s not as if the passage of time somehow erased the very existence of the Pfaff’s Bohemians. They’ve been here all along. They’re like restless ghosts—elusive, flickering, unsettled.

Justin Martin is the author of Greenspan: the Man behind Money, Nader: Crusader, Spoiler, Icon, and Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted (recently excerpted on Gotham). His articles have appeared in a variety of publications, including Fortune, Newsweek, and the San Francisco Chronicle. He lives in Forest Hills Gardens, NY.

* This post is an excerpt from the author's new book Rebel Souls: Walt Whitman and America's First Bohemians, reprinted courtesy of Merloyd Lawrence Books / Da Capo Press.