Those Who Know Don’t Say: Interview with Garrett Felber

Interviewed by Kenneth M. Donovan

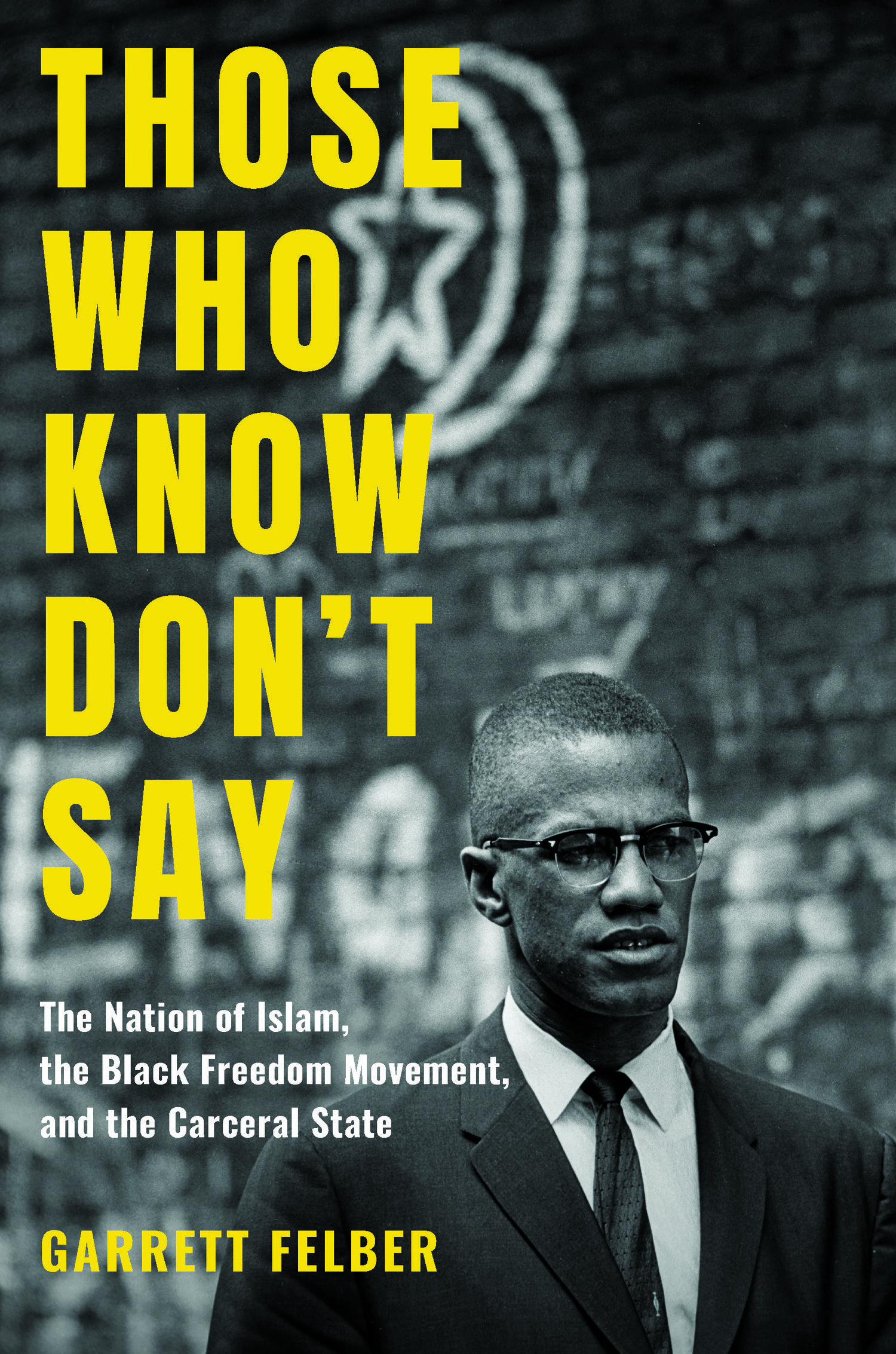

Today on the blog, Kenneth Donovan interviews Garrett Felber about his recently published book Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, The Black Freedom Struggle, and the Carceral State. Those Who Know, which reevaluates the civil rights activism and legacy of the Nation of Islam, was shortlisted for the 2020 Museum of African American History Stone Book Award.

Can you tell us a little about how you came to work on the Nation of Islam?

This work started for me when I joined the Malcolm X Project, directed by Dr. Manning Marable at Columbia University, as a research assistant in 2008. It was a robust, decades-long project that I came to in the final years leading up to the publication of his Pulitzer prize-winning biography, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. During those years, Dr. Marable would pose the question of whether Malcolm’s break with the Nation of Islam (NOI) was driven by the political or personal — over his diverging strategic vision from Elijah Muhammad and other leadership in Chicago or his devastation at learning of Muhammad’s affairs with young secretaries in the Nation, one of whom Malcolm had once been engaged to.

Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State

By Garrett Felber

University of North Carolina Press, 2020

272 pages

But several unspoken pieces of that question, especially in relation to what I was finding in the archives, continued to linger enough to prompt my writing this book on the NOI and its politics. The first was the focus on top-down leadership and the idea that the politics of a mass organization could be discerned from those in elite positions. The second was this division between Malcolm as political and the NOI as apolitical. And the last was a “reading backwards” of Malcolm’s departure from the NOI (which is common among many of the harshest critics of the NOI) so he is depicted as ideologically outside an organization of which he was once the national spokesperson.

A great deal of my thinking on this subject is also owed to a fellow Malcolm X Project researcher, Zaheer Ali, who is writing a brilliant dissertation on the Nation of Islam in New York. I came to radically different conclusions about the NOI than did Dr. Marable, who passed suddenly of complications from a rare lung disease in 2011. But I am grateful that I was able to do so through my work with him, which is evidence of the value he placed on scholarly and political disagreement as generative.

Discourse and knowledge production surrounding the NOI play an important role early in the book. What was — and maybe still is — the popular perception of the NOI and to what extent does your work challenge these perceptions?

Judging from the number of journalistic requests I get to discuss the Nation of Islam as anti-Semitic or a “hate group,” I’m afraid the current popular perception of the NOI owes much to the discourse of Cold War anticommunism and racial liberalism prevalent when the NOI first came to the attention of the mainstream media in the late 1950s. Whether in the FBI’s leaked “Black Identity Extremists” report or through liberal advocacy organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center, the NOI remains popularly identified with hate and extremism. This was precisely the same terrain that Malcolm X was navigating in 1962 in Los Angeles when he delivered one of his greatest speeches after the police killing of Mosque secretary Ronald Stokes and riffed on the question “who taught you to hate?”

The second popular misconception, also rooted in midcentury politics and inextricably linked to the first, is the idea that Muslims in the Nation of Islam are not recognized as “true” or “authentic” by other Muslims. While it may be true that many Muslim groups do in fact distance themselves from the NOI, I would argue this is cannot be separated — as it could not then — from anti-Blackness and anti-radicalism. That’s not to downplay the significance of theology or religious practices, but rather to suggest that you cannot answer this question without considering structural racism and state violence.

In the introduction to the book, I quote Malcolm X after he had left the Nation of Islam. He said, “No matter what you think of the philosophy of the Black Muslim movement, when you analyze the part that it played in the struggle of Black people during the past twelve years you have to put it in its proper context and see it in its proper perspective.” At the most basic level, I wanted people to interrogate where their ideas about the Nation of Islam come from and realize how embedded [they] are with white supremacy and Islamophobia.

A central theme of the book is a relationship you call the “dialectics of discipline.” Describe that process for us. What does it reveal about the relationship between the state and the NOI, or social movements in general?

I’d like to start with the caveat that while I am an unqualified lover of alliteration, I do not necessarily love the idea of “coining” theoretical phrases. But that disclaimer aside, I needed a conceptual way of braiding together the big and small ways that Muslims were in relationship with the state (and the carceral state more specifically) in an explanation that was not linear, but dialectical.

Dialectics here most basically refers to the relationship and interplay of two opposing — and therefore mutually constituting — sides (ie. prisoner and captor; police and those policed). And as they struggle against one another, new modes of organizing emerge and the state creates new mechanisms of repression.

Discipline has three meanings as I use them in the book. The first is discipline as coercive social control by the state. This took the form of surveillance, infiltration, harassment, racial and religious profiling, mosque raids, solitary confinement, and fatal police shootings, to name just a few of the most violent and obvious forms of state disciplining of the NOI. The second is a resistant self-discipline that was both individual and collective. Personal discipline ranged from immaculate dress and healthy eating, to prayer, tithing, and a refusal to smoke, drink, or curse. Public displays of collective discipline included security, hunger strikes, and takeovers of solitary confinement. The third and final meaning is disciplinary knowledge, which you get at in your previous question. Foucault writes that “power and knowledge directly imply one another.” Journalists, scholars, police, and prison officials all gathered, compiled, interpreted, and disseminated “knowledge” about the NOI which has distorted our understanding of its politics to this day.

I’ll give a concrete example of the dialectics of discipline because, as one of my favorite historians Ula Taylor admonishes, your theory is only as good as your archive. In the early 1960s, incarcerated Muslims were seeking basic religious rights such as correspondence with ministers, access to the Arabic translation of the Qur’an, and space for religious services. As they organized around these demands, prison officials disciplined them through solitary confinement and losses of good time (thereby increasing the likelihood of them serving full sentences). Muslims began suing wardens and prison commissioners for violating their constitutional rights, a strategy which became so effective that Muslim organizer Martin Sostre called pens, notebooks, and paper their most “essential weapons.”

Since jailhouse lawyers like Sostre were drawing up these legal challenges on behalf of multiple prisoners, officials created and enforced rules which prohibited one prisoner from preparing legal papers for another. Those found with legal materials in their cell were again punished by being sent to solitary confinement. Sostre concluded that when “the box [solitary confinement] ceases to work, the entire disciplinary and security system breaks down.” Therefore, he and other Muslims purposefully committed infractions to fill the solitary confinement gallery in a strategy which mirrored the “Jail, No Bail” campaigns of the civil rights movement in the US South. Here, is one of the most obvious cases of coercive state discipline being met with collective discipline as resistance.

These dialectics can appear to some people like a sort of hamster wheel where individual people move but we collectively go nowhere. But on the contrary, dialectics actually drive movements — and history — forward. As Orisanmi Burton recently argued, “prison abolition is about breaking this dialectic of rebellion and counter-rebellion, which has been so central to US carceral development.” Organizing is about creating new horizons of struggle, so our goal is not to transcend dialectics themselves, but to remake the conditions of our world through them.

You write that “the broader history of the Nation of Islam and the carceral state… demonstrates the deep intersection of race, gender, religion, and nationhood.” Can you share some examples of how these intersecting forces shaped the NOI and its activism?

Yes, that’s a great question. I think when Muslims in the Nation of Islam are first incarcerated en masse during the 1940s is a place where we can see these intersections very clearly. As I document in the first chapter of the book, Muslim men comprised the largest segment of Black draft resistors in the country during World War II, something rarely remarked upon in most tellings of US history during the War. This was during a period when military service was being used as a leverage point to demand fuller citizenship by many African Americans through efforts such as the Double V campaign, which called for victory against fascism abroad and racism at home.

But the Nation of Islam’s refusal to register with the selective service was neither consistent with the most civil rights groups at the time, nor many of the 6,000 conscientious objectors with whom they served time in federal prisons, such as pacifists or absolutists (those who refused to do any work related to war or obey military orders). Muslim draft resistors did not consider themselves citizens of the United States, refused to fight a war on its behalf, and instead sided with the Japanese, whom they identified as part of a rising global order of people of color which would challenge worldwide white supremacy.

Despite a few prominent cases of Black women getting tried and jailed for sedition or conspiracy during World War II — most notably Mittie Maude Lena Gordon of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia whom Keisha Blain has written about extensively — this persecution by the state was gendered in that it reinforced, and was couched in, understandings of masculinity which coupled manhood with conscription.

When Muslim men were imprisoned, they were disciplined in ways that intertwined religion and race so as to make them almost indiscernible. For example, Willie Mohammed was forbidden from seeing his wife because he wouldn’t give his “original (‘slave’) name.” Isaiah Edwards was transferred for his agitation around the “race question” and reportedly continued to “preach from segregation” (solitary confinement). The men were largely segregated to units both by race and religion, and when asked to join a hunger strike against racial segregation by non-Muslim Black activists, they declined.

These are all scattered examples during this period, but what you had was two nations for whom race, gender, religion, and nationhood were completely intertwined: the United States and the Nation of Islam. And perhaps seeing it in the context of the NOI helps us recognize more plainly how US citizenship is shaped and curtailed by religion, race, and gender.

How do you think we should see the NOI in the broader context of the Black Freedom Struggle? What does Those Who Know force us to reconsider about popular narratives of the Civil Rights Movement?

I did a lot of thinking and writing of this book (and before that, the dissertation) in the context of the debates about the “long civil rights movement.” There were suddenly openings to consider the Black freedom struggle in a wider temporal and geographical plane than the traditional civil rights movement frame had offered (and I would add to that a renewed focus on women’s leadership, self-defense, and local and bottom-up organizing). And yet there were still things conspicuously absent.

So I ask in the introduction to the book for us to consider these silences. What does it look like to take a scene like I document at Folsom prison in 1962, where Muslim men are praying under surveillance in protest, and place it at the center of the midcentury Black freedom struggle? What are the implications in understanding the purposeful filling of solitary confinement by Muslims at Attica in 1961 as similar to — and even anticipating — the strategy of “Jail, No Bail” in the Albany Movement? Why is one remembered and one hardly told?

I hope that the book encourages readers to think more deeply about the erasures and advanced marginalization (to borrow Cathy Cohen’s term) of people in every movement. Because in the case of incarcerated Muslims in the Nation of Islam, they were encountering not only the blunt instruments of state violence, but also anti-Blackness and Islamophobia within religious and activist communities. So when I hear people talk about mass incarceration as the “civil rights issue of our time” it makes me wonder about our collective understanding of the civil rights movement itself, and our connections to those struggles. It’s easy to say police killings, solitary confinement, and other forms of state violence are not new. But it’s much more difficult — and more importantly, much more valuable — to understand that neither are the movements against those forces, and that there’s something to learn in the questions they grappled with and the success and shortcomings of their organizing.

Is there anything else you would like to add about Those Who Know Don’t Say?

No, just that I’m always truly humbled when people read and engage with the book. So, thank you for facilitating that and allowing me the space to share.

Garrett Felber is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Mississippi. His research and teaching focus on 20th-century African American social movements, Black radicalism, and the carceral state.

Kenneth M. Donovan is a PhD student at Stony Brook University. His research interests include 20th century U.S. history, housing and education, civil rights, and the racial geography of suburban space.