The Regional Nationalism of New York’s Literary World

By Alex Zweber Leslie

A star-studded list of proposed contributors in an early draft of the Literary World’s prospectus. Ducykinck Family Papers, New York Public Library.

In the 1840s literary New York was electric. The city was booming, and its material success fueled a surge in cultural aspirations. A new generation of authors, including Herman Melville, joined an influx of emigres such as Edgar Allan Poe and Caroline Kirkland, while old standbys like Washington Irving became firmly canonical. An explosion of new magazines devoted to arts and politics meant that there were ever more writing in print and editorial sides to take. Boston may have still been the nation’s cultural capital, but New York was experiencing a renaissance that shifted the regional balance of cultural authority. It was a world of tightly-knit cliques, petty rivalries, inside gossip, playful pseudonymity, waggish jokes, and, most of all, youthful hopes for the future of literature in America.

For all this, was there really such a thing as a distinctively American literature? This was the question on everyone’s lips, unexpected as it may seem for the era that has since been dubbed the “American Renaissance.” Critics of the day were uncertain about what would stand the test of time, and they were deeply divided on which qualities should be reflected in an American aesthetic. Disagreements especially flared up between the intellectual communities of different places. As a result, literary differences were mapped onto geography and geographic differences were projected onto literature. Each region of the country had its own distinctive vision of what the national culture should look like, visions which invoked an imagined national ideal on behalf of the fundamentally regional interests underlying them. I call this rhetorical strategy and the mindset it reflects “regional nationalism.”

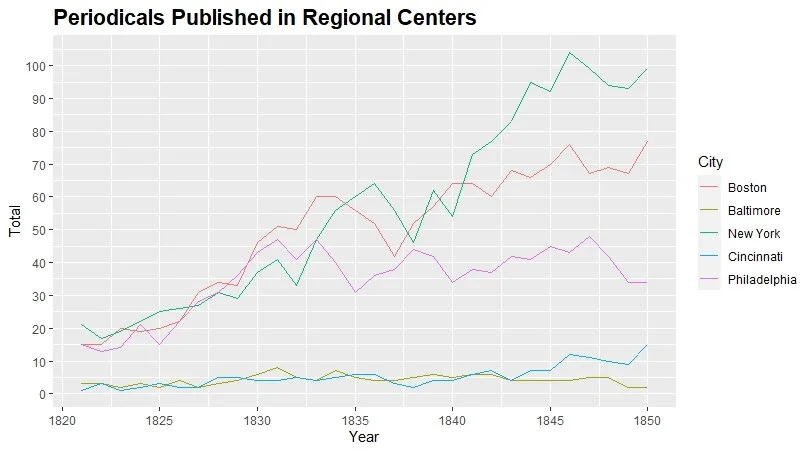

In the early 19th century American publishing, like many other industries, was regional. Comparatively high transportation costs combined with comparatively lax copyright regulations incentivized a market geography of dispersed reprinting hubs with shorter distribution chains. Magazine and book publishers tended to cluster in urban areas centrally located within regional networks: chief among these were Boston for New England, Cincinnati for the adolescent West’s Ohio River Valley, Philadelphia for the “Middle States” as well as parts of the South, and a combination of Baltimore, Richmond, and Charleston for the rest of the South.[1] As mid-century approached an ever-greater proportion of the nation’s publishing was done in New York, Boston, and, to a lesser extent, Philadelphia; by century’s end centralization would culminate in the dominance of New York. But this eventuality, like the literary canonization of Melville or Poe, was still far from certain at midcentury. New York was still a region in competition with others.

Active periodicals per year in several major publishing centers based on the holdings of the American Antiquarian Society.

The spaces of cultural geography can be surprisingly fluid. New York is a city, but it is also a state and, what’s more, a state that dubs itself something even broader with the epithet “the Empire State.” Indeed, it was codependent on networks of economic, cultural, and human circulation that incorporated parts of Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, southwestern Connecticut, and southern Ontario. In the antebellum period “New York” referred to this regional system as much as it did to the city or state. New York’s advocates in culture and commerce used to their advantage this slippage between the concentric spaces of city, state, region, and — with the discursive technique of regional nationalism — even made it stand in for nation or “empire.”

Nassau Street and environs in the 1840s identifying several key firms, offices, and institutions of New York’s literary hub.

The community at the core of literary New York was a small world despite its wide impact across this network. One could pass the editorial offices of all the important newspapers and magazines by walking eight blocks down Nassau Street, the city’s original “Newspaper Row,” conveniently anchored by the Post Office.[2] Stepping one block over to Broadway one would find many of the city’s prominent publishers, and numerous printers, type foundries, and stationery suppliers had set up shops on the intersecting Fulton, Ann, and William Streets.

Predating the hard separation of disciplines, periodicals intermixed art, politics, science, and economics as interconnected. There was the Democratic Review, whose editor John O’Sullivan coined the term “manifest destiny” and published pieces by many leading authors including poet William Cullen Bryant, editor of the Evening Post. Its Whig Party counterpart, the American Review, published Poe’s “The Raven.” Poe himself took a turn editing the Broadway Journal with Charles Briggs, a New York author of Wall Street satires in the Knickerbocker, named for Washington Irving’s doting narrator.

Foremost among these commentators was the Literary World (1847-1853), a trade journal edited by literary kingmaker Evert Duyckinck. Duyckinck was a vital node in the city’s intellectual network. He had written in almost every major periodical in the city in the decade before founding the Literary World; he provided critical support for the careers of Poe and Melville (facilitating the latter’s watershed introduction to Hawthorne) as well as numerous lesser lights of New York such as Cornelius Matthews; as the series editor of Putnam’s Library of American Literature he had considerable sway in early canon formation debates.

The Literary World embodied New York regional nationalism. As a reflection on the “Schools of American Literature” pronounced, “we shall endeavor to keep the windows of our writing-chamber open, North, South, East, and West: and this we take to be the best province and happiest good fortune of our metropolitan position. While jealousies and heartburnings are indulged elsewhere, New York stands central.”[3] Familiar as this call to cosmopolitanism may sound today, it was regionally distinctive at the time. Broadly speaking, New England critics tended to emphasize intellectual training and English heritage, Southern critics tended to emphasize cultivated manner and stylistic grace, and Western critics tended to emphasize first-hand experience and natural genius. The Literary World’s critical apparatus defined New York against what it took to be the excesses of its rival regions — it was more vibrant than New England, more jocular than the South, more cultured than the West — though what this meant in practice varied depending on the subject’s relation to New York. Most important of all, this account located cosmopolitanism specifically in New York, deeming it the uniquely representative region and thus the true model for literary nationalism.

Critics never speak solely for themselves, of course. A periodical is a dialogue between writers, editors, and readers, negotiated through the continuous exchange of copies and dues. If a periodical speaks to and for readers of a particular class or group, those readers subscribe; if not, they cancel. This exchange, moreover, always unfolds across space. A region is the geographic aggregate of these individual acts of participation. Nassau Street didn’t represent just a city or state but a region, capable of growing or shrinking with readerly interest. Indeed, in the era of Manifest Destiny and the Missouri Compromise, writers contested regional nationalisms precisely because they understood influence and space as intertwined.

Postal locations of Literary World subscribers in mid-1851.

Mapping circulation brings the contours of this geography into focus, and Literary World subscription records serve as a generalizable case.[4] Reading the Literary World had a cultural valence not unlike reading the New Yorker today: it marked one as possessing the empire state of mind, even if from a distance. The areas where Literary World subscribers cluster indicate the region of New York (along the Mid-Atlantic, the St. Lawrence River, and Lake Eerie, for example) while high-population areas with few subscribers outline its limits (such as Pennsylvania, New England, and central Tennessee). Major cities naturally all have Literary World subscribers, but those outside the region have disproportionately fewer (Montreal had as many as Boston with only half the latter’s population and intellectual community). This is the feedback loop in which New York regional nationalism flourished. It does not fit the static idea of region that we sometimes imagine when looking at filled-in shapes on a map; it is instead a dynamic, variegated terrain of continuous cultural negotiation.

In A History of New York Washington Irving had lovingly teased the city’s Dutch forefathers for an obsession with their britches; authors in the 1840s felt rather that New Yorkers of the day were getting too big for theirs. As the Boston poet Oliver Wendell Holmes humorously complained in verse,

The pseudo-critic-editorial race

Owns no allegiance but the law of place;

Each to his region sticks through thick and thin,

Stiff as a beetle spiked upon a pin

[...]

But Hudson’s banks, with more congenial skies

Swell the small creature to alarming size[.][5]

Holmes singles out New York critics as especially over-attached to their region. In the image of the swelling beetle he parodies New Yorkers’ attempts to make their region stand for the nation, but beneath this comic exterior lies real alarm. After all, regional borders were not static; they fluctuated with the expansion and contraction of networks of circulation and influence. Thus Southern critics protested the influx of books from other regions, and thus Western critics’ lamented that other regions were poaching their authors. New York’s claims to represent the whole nation may have seemed laughable in 1848 to his fellow New Englanders, but Holmes suggests that they just might come true. We now know that, in a way, they did.

The Literary World came to a premature end, like many of its New York peers, in the tumultuous decade leading up to the Civil War. Little wonder: a regional nationalism premised on one cosmopolitan region’s ability to represent the whole nation became increasingly untenable as the regions of that nation split apart. After the war material shifts transformed the face of publishing within the city and without. Newspapers would first creep north to Park Row before jumping to Midtown at the turn of the century, and magazine offices became more dispersed across Manhattan as their numbers increased. Yet the New York regional nationalism formulated in the 1830s and 1840s has proven considerably more lasting in its influence on our imagination of the nation’s metropolis.

Alex Zweber Leslie is a PhD candidate in English at Rutgers University. This blog post draws from his article “Regional Nationalism and the Ends of the Literary World,” which appeared in J19: he Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists in Fall 2019.

[1] Periodical publishing figures drawn from the American Antiquarian Society holdings; a tidied copy of this data is available at https://azleslie.com/data/antebellum-periodicals/.

[2] Doggett’s New York Directory for 1847 & 1848 (New York: John Doggett Jr, 1847). Accessed at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009008893.

[3] “Review: Schools in American Literature,” Literary World, October 19, 1850, 308.

[4] Unmarked pink-, green-, and yellow-marbled book, Box 59, Duyckinck Family Papers, New York Public Library.

[5] Oliver Wendell Holmes, Astraea: The Balance of Illusions (Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1850), 31.