Notes on the Planned Town of Fort Amsterdam

By Richard Howe

The three locations for the 1625 settlement mentioned in the West India Company’s instructions to Provisional Colony Director Verhulst, in rank order of the Company’s stated preference: 1) High Island; 2) “where the runners pass from the North to the South river”; 3) the “hook” of Manhattan.

As little as we know about the 1625 Manhattan settlers and what they did when they first got to the island in the late spring of 1625, we do know what the West India Company had instructed Provisional Colony Director Willem Verhulst to do, which was not to settle on Manhattan but rather on High (Burlington) Island in the South (Delaware) River. High Island was, in the Company’s opinion, more suitable for settlement, though the Company didn’t exclude the possibility of its being established at “the hook of the Manattes,” or, and preferably, if not on High Island, then “about where the runners pass from the North to the South river,” which may have been on the west bank of the North River opposite lower Manhattan.

The West India Company instructed its on-site engineer and surveyor, Krijn Fredericxsz, that the fort was to be called “Amsterdam,” but didn’t say where it was to be built. — “As soon as the outer ditch shall have been almost completed, Commissary Verhulst . . . shall at once have the construction of the fort, which is to be called Amsterdam, begun . . . the specifications of which fort are as follows . . .” (facsimile and translation from van Laer’s Documents of New Netherland 1624–1626).

What in fact happened was that the new arrivals all settled on the island of Manhattan, and not on High Island in the South River. But in any case, Verhulst was instructed first of all to have the site surveyed and platted, and then to grant the lots to the settlers. The carpenters were to cut timber with which to build temporary houses, barns, and other storage facilities. The instructions said nothing about these temporary buildings beyond noting that “for the present [it would be] sufficient if they are tight and dry, without ornament, in order that no time may be lost.” The specifics of their construction were left up to the carpenters and other craftsmen, whose prior experience in the Dutch Republic and elsewhere the Company could rely on.

The fortified Dutch town of Deventer in the seventeenth century, one of the many cities and towns in the Dutch Republic that were enclosed within bastioned earthworks to defend against Spanish and other artillery after the Dutch declared their independence from Spain in 1581. (Image: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen)

The West India Company also ordered fortifications to be built for the settlement, for which it supplied specifications that were as detailed as those for the temporary barns and houses were not. This was surely because forts were important to the Company, which had been founded on a war footing, but it could also be that the planners simply knew more about forts than they knew about houses and barns, and therefore had more to say about them. By 1625 the Dutch had accumulated a lot of experience with fortifying towns in the Dutch Republic. They had also learned a lot about planning and fortifying their commercial outposts overseas. The 1625 settlement in New Netherland would be their 51st such outpost since the East India Company established its Portudale outpost on the west coast of Africa in 1595.

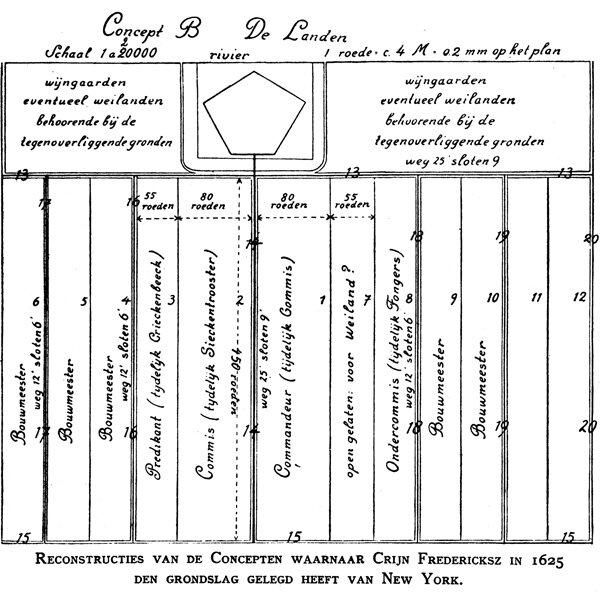

Dutch overseas town plans generally specified locations, fortifications, street layouts, and building designs and materials, and the specifications that the West India Company gave Fredericxsz were no exception, specifying in some detail the settlement’s streets and roads, the size and shape of its fortifications, the sizes of its houses, and the sizes of the fields adjacent to the town. Verhulst’s instructions had called for barns, storage places, and a sawmill, but Fredericxsz’ instructions made no mention of them. Verhulst’s instructions had also specified the size of the lots to be granted to each family: 600 × 2,400, or about 33 acres (I have converted the plan’s old Amsterdam measures to our feet). Fredericxsz’ instructions didn’t mention these lots either, but they did specify 10 much larger ones for the head farmers and the Company’s officials, eight of them to be 660 × 5,400 feet (about 82 acres) and the other two to be 965 × 5,400 feet, (about 120 acres).

F.C. Wieder’s 1925 drawing of his reconstruction of the overall layout of the planned area of the settlement (6,686' × 6,500'), based on the instructions to Fredericxsz. (Image: Wieder’s De Stichting van New York)

The settlement was to face the river — the instructions didn’t say which river — within a rectangle 1,858 feet long and 1,486 feet wide. One of the two long sides was to be the shoreline of the river, the other three sides were to be bounded by a ditch, 22 feet wide and three feet eight inches deep. Within this perimeter ditch a five-sided fort was to be built, some 929–975 feet in diameter. The ramparts of the fort were to be 37 feet wide, their outer walls sloping up at about a 45º angle to a height of 18 feet six inches, surmounted by a parapet five feet six inches high, with a walkway 13 feet wide along the top of the ramparts behind it. The downward slope from the walkway into the town wasn’t specified, but 45º would be a good middle of the road guess, which adds 18 feet to the width of the ramparts, bringing the total up to 56. The drawings that accompanied the Fredericxsz’ instructions could tell us what slopes the Company actually had in mind, but, alas, the drawings have been lost, along with so much else.

Cross-section of the ramparts in F.C. Wieder’s interpretation of the instructions to Fredericxsz. Wieder gave the outer wall of the ramparts a steep slope, making the rise to 18' 6" in the space of 9' 3" instead of 18' 6", for an angle of 63º. (Image: Wieder’s De Stichting van New York)

Fort Amsterdam was probably intended to be a “star” fort, in this case a regular, i.e., equal-sided / equal-angled pentagon, with bastions at each of its five points. Bastions are earthworks more or less in the shape of arrowheads protruding outward at intervals from ramparts. Bastioned earthworks had emerged in Tuscany in the 16th century as a response to the new threats posed by cannons and muskets. Earthworks resisted cannon fire much better than masonry walls, and bastions made the entire perimeter equally defensible, so that there were no particularly weak places at which an attack could most effectively be concentrated. As a further defense for the settlement, there was to be a moat 50 feet wide and seven feet five inches deep in front of the outer walls of Fort Amsterdam’s ramparts and bastions.

There was nothing odd or unusual about the West India Company’s planning their new outpost as a fortified town. Ever since the seven northern provinces of the formerly Burgundian Netherlands had abjured the sovereignty of their by then Hapsburg monarch, Philip II of Spain, in 1581, the loose confederacy that was the Dutch Republic had been fortifying the perimeters of its cities and towns with bastioned earthworks, as the 17th century towns of the Republic amply demonstrate. The Dutch trading companies also used bastioned earthworks to fortify many of their outposts overseas, and where a fully fortified town was deemed unnecessary they often built small forts within the town. Bastions were by no means a Dutch exclusive: they were a commonplace of fortification everywhere.

The East India Company’s plan for its fortified outpost at Jaffanapatnam (Jaffna, in Sri Lanka), 1693. (Image: Dutch Atlas of Mutual Heritage)

Fort Amsterdam was not meant to be built within the town; rather the town was to be built within Fort Amsterdam, i.e., the settlement was conceived to be a fortified town, its earthworks and bastions no more than a modern update of the underlying medieval concept of a town as a walled settlement. The plan called for 110 houses to be built within the ramparts, plus a large building that would serve as a church, a school, and an infirmary. The town’s streets were specified, as were two roads outside the perimeter ditch. Ten farmhouses were planned outside the ramparts but within the perimeter moat, bringing the total number of houses to 120.

F.C. Wieder’s 1925 reconstruction of the ramparts and bastions of Fort Amsterdam, together with layout of the streets and houses within it, based on the instructions to Fredericxsz. (Image: De Stichting van New York)

All but 25 of the planned houses were to be (in round numbers) about 23 feet wide and variously 32, 37, and 46 feet deep on their lots; one of them was to be a 46 foot square, and 20 were to be 18 feet six inches by 37 feet. The remaining four were small triangular odd lots resulting from the pentagonal shape of the fort and suitable only for tool sheds and the like. The 10 houses outside the fort were to be for the five head farmers, two foremen, the comforter of the sick, and the two deputies for commerce. These houses were to be of a type that the company planners called “model E” and provided drawings for, but neither the drawing(s) nor the written specifications for the model E houses have survived. They might have been common rural Dutch house barns, with living quarters in front and cattle stalls in the back, but this is just a conjecture, though not an implausible one.

Eighty-four of the houses were to be of a type that the Company called "model D." Here too drawing(s) were made, but have not survived; however, the written specifications have survived, at least for the main block of 24 houses, including a double width house for the commissary (the chief commercial agent). A model D house was to be 23 feet square and built to a height of two stories plus a garret or attic under the roof. The first story was to be 14 feet high, the second eight feet four inches high. The pitch of the roof — and thus implicitly height of the garret — was not specified, or if it was, it was so only in the drawings. The first floors and the garrets were for the residents. The second stories were to be a loft space for the company, with adjacent lofts connected by doors between them. Left unsaid was whether these houses were to be built as row houses with party walls between them, and whether their gable ends were to face the street, like the houses in Amsterdam, or to be perpendicular to it, and, if so, whether the roofing was to be continuous across the whole row of them.

The model D houses were to be roofed with thatch or straw if available, though it was allowed that wooden shingles might be used if they were not. Exterior wall materials were not specified, but brick would have been very Dutch, and many of the later houses in New Amsterdam were faced with brick. But bricks in the quantities that the plan would require would have been far too many to bring over from Amsterdam as ballast (though some doubtless were), so brick walls would have to wait until the settlers could make their own. Kitchens were to be 10 feet deep for houses on lots 32 feet deep, but were allowed to be larger in houses on lots 37 or 46 feet deep. The very first four houses to be built were initially to have no “inside work” — meaning no interior partitions — in order to be able to house the first settlers communally while the rest of the houses were being built. It is likely that all the houses were intended to be ordinary “Nederlandic” construction: a series of “bents” (framing units) at eight to 10 foot spacings, connected by beams.

An example of Nederlandic timber framing: though the loss of the drawings for the Company’s “model D” and “model E” houses leaves us without answers to many questions about how they were designed and built, it is likely that they would have been framed much like this, or a some slight variation of it. (Image: adapted from Steven’s Dutch Vernacular Architecture.)

Historical demographers usually assume a ratio of three and a half to five persons per house for this period in European history; their ratios suggest that Fort Amsterdam as planned by the West India Company would eventually accommodate 385–550 settlers resident within the ramparts, with another 35–50 outside (these and the following figures are to be understood as no more than very rough indicators). The plan also implies (without being explicit) an initial settlement in the range of 24–30 families, perhaps in the range of roughly 84–150 souls. The plan left enough open, unused space within the ramparts for another 50 or so houses, i.e., for another 175–250 residents. So all in all the Company foresaw a town of about 600–800 souls, plus the 30–50 on the 10 principal farms, though the number of farms would surely have to grow along with the in-town population, if everyone was to be fed. Further growth was meant to be not only outside the ramparts but outside the perimeter ditch as well.

Even on the scale of late medieval to early modern European towns, the town of Fort Amsterdam would have been a small one. In its early years, when the population numbered only a few hundred, Fort Amsterdam would scarcely have qualified as a village in 17th century northwestern Europe. Recent scholarship argues that at the time of the English takeover in 1664 the town’s population would have reached some 2,500 (Africans included, and taking natural increase as well as immigration into account). This was enough to call it a town, though not really enough to call it a city, the population threshold for which historical demographers usually put at about 5,000 in late medieval to early modern Europe. If anything was unusual about Fort Amsterdam, it was that the West India Company would plan to fortify such a minor outpost in this way. This may have simply been a mistake of the kind that bureaucracies of all kinds, even 17th century Dutch monopoly trading companies, are prone to making, namely doing — or at least attempting to do — only what they know how to do, no matter whether this is appropriate to the situation or not.

The extent of planned settlement was also not large. The area bounded by the perimeter ditch and the river came to a little over 63 acres; the area within the ramparts would have been not quite 12 acres and the area available for building about 10 acres. The whole area of the settlement, including the lots planned for the head farmers and the company officials, but excluding the lots to be granted to the families, came to about 1,000 acres: a not quite square rectangle with the longer sides just over a mile and a quarter long, and the shorter sides just under a mile wide; an additional 600–1,000 acres would be needed for the lots allocated to the families. One of the two long sides of the planned area was to face the river. Although the Company’s specifications didn’t say where the settlement was to be located, they are specific enough for us to see how close to the southern end of Manhattan it could have been if it were located there and if it were built to plan.

The southernmost point on Manhattan’s 1609 North River shoreline where the southwest corner of the settlement could be located and still have the settlement extend a mile and a half inland would be roughly — very roughly! — at the corner of today’s West Broadway and Park Place; the southeast corner at Clinton and South Streets; the northeast at First Avenue and 11th Street, and the northwest at Greenwich and Gansevoort Streets. This would put the southern edge of the settlement about half a mile north of what was in 1625 the southernmost tip of “the hook of the Manattes,” which in turn suggests that the plan was never intended for Manhattan, since it’s unlikely that the Company would want to leave that much open space south of the settlement for a hostile force to assemble in. But the plan could not have been intended for High Island either, which is only about 300 acres in extent, and the plan calls for 1,000 acres. There would have been enough open space on the west bank of the North River opposite lower Manhattan, but in 1625 no one seems to have given that alternative much if any thought.

The shoreline of Manhattan in 1625 meant that had the West India Company’s plan been followed exactly, its southern border could not have been much below a line running approximately between the intersection of today’s West Broadway & Park Place and the intersection of Clinton Street and South Street, if it were to all be on dry land. (Image: OASIS Project view current street plan superimposed on Eric Sanderson’s reconstruction of Manhattan circa 1600.

What are we to make of this? Even allowing for the Company’s understanding that such plans have to be adapted to local circumstances, the gap between the plan given to Fredericxsz and the reality of Manhattan is huge. The most charitable suggestion might be that the plan was meant only as a kind of ideal, with no expectation that any reality would ever match it; another might be that all that really mattered was the approximate sizes of the houses and lots, together with stipulation that most of the houses be built within a bastioned earthworks or ramparts, surrounded by a moat and in turn surrounded by a ditch. A less charitable, but perhaps more likely explanation, is that the people at the West India Company who drew up the plan were overworked and in a hurry and just threw something together at the last minute to satisfy their superiors, in form if not in substance, knowing that their superiors wouldn’t have the time or the inclination to review the substance of the plan in any detail. The fact that their instructions to Fredericxsz don’t match up with any of the plan’s suggested locations for the settlement in turn suggests that the planners didn’t know much if anything about their proposed sites. Overwork and haste plus ignorance: it wouldn’t have been the first time this combination was the basis for a plan, nor would it be the last.

Detail from the 1639 “Manatus” map of New Amsterdam. All that remains of the West India Company’s original plan for the settlement is the four-sided fort drawn in red at letter A, next to the two windmills marked C and B. (Image: Library of Congress)

As so often happens with the grand plans of a home office for a remote site — even today — the West India Company’s instructions to Verhulst and Fredericxsz had a rough landing on the far distant field to which they were dispatched. It was soon apparent that the Company’s plans for the settlement not only didn’t fit the geography of Manhattan but were altogether too ambitious to be undertaken by what all in all could not have been much more than 150 or so people to begin with, if that. The southern tip of Manhattan was heavily forested, although there may have been some clearings by the native Americans or by the Nut Island settlers — if indeed there were any — so the Company’s plans would have required the settlers to clear at least 1,000 acres of forest, plus another 600–1,000 acres for the families fields and pastures, something that could have taken 100 able-bodied men as much as a year or more to accomplish. The settlers had neither the material nor the human resources to execute the Company’s plans for the planned town of Fort Amsterdam: their top priority in the late summer and fall of 1625 was simply to build enough temporary barns and houses — no matter how temporary — to enable them and their cattle to survive the coming winter.

The West India Company’s plans were dropped right away, never to be taken up again. The town of New Amsterdam that was built instead was almost the exact opposite of the town planned by the Company: the fort was in the town rather than the town in the fort; it was much smaller than the one called for by the plan, and four-sided rather than five-sided; its ramparts were supposed to be faced with stone, but they were not. The scaled-back Fort Amsterdam was, at least, bastioned, or so it appears in the famous 1639 “Manatus” map attributed to the Amsterdam cartographer and painter Johannes Vingboons. The town of New Amsterdam itself was unfortified: even the eponymous wooden palisade that was later built along what is now Wall Street could hardly be called a fortification, at least not in comparison to what the West India Company originally had in mind for Fort Amsterdam.

Though there’s not much we know for sure about what the 1625 settlers were doing when they arrived on the island of Manhattan, we can say this much: they were not building the planned town of Fort Amsterdam, and — above all, because it is so easy to forget — they were not founding the City of New York, or anything like it. Nor were they founding a “citty upon a hill, the eies of all people uppon them” — Colony Provisional Director Verhulst was no Winthrop, and neither, later on, were Minuit, Krol, van Twiller, Kieft, or, for that matter, Stuyvesant. What the settlers were doing on Manhattan in 1625 was surviving, and — as it turned out — that was enough for them to have left their mark on history.

Richard Howe is a frequent contributor to the Blotter, and is writing a history of New York as a built environment. He runs the photographic study New York in Plain Sight: The Manhattan Street Corners.

Further reading

The West India Company’s 1625 instructions to Verhulst and Fredericxsz are translated in A. J. F. van Laer’s 1924 Documents of New Netherland 1624–1626, never reissued, but the texts and notes are on-line at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nycoloni/huntoc.html.

F. C. Wieder’s 1925 study De Stichting van New York in Juli 1625 (The Founding of New York in July 1625) has never been translated and also never reissued, but Wieder’s drawings of his reconstruction of the plan of the settlement are reproduced in John Rep’s 1965 The Making of Urban America, still in print.

Jaap Jacob’s 2009 The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America provides a thorough introduction to the colony of New Netherland, and Jan de Vries’ 1976 The Economy of Europe in an Age of Crisis, 1600–1750 is a concise introduction to the European background.

Ron van Oers’ 2000 Dutch Town Planning Overseas during VOC and WIC Rule 1600–1800 surveys the East and West India Companies’ overseas settlements, and includes a detailed atlas of nineteen of them.

Jeroen van den Hurk’s 2006 dissertation Imagining New Netherland: Origins and Survival of Netherlandic Architecture in Old New York analyzes the relationship of seventeenth century building practices in New Netherland to those in the Netherlands.

John R. Steven’s 2005 Dutch Vernacular Architecture in North America, 1640–1830 is a treasure trove of photographs, drawings, and analysis of Dutch buildings and building practices in the New World.

Len Tantillo’s 2011 The Edge of New Netherland provides an excellent account of the seventeenth century Dutch fortification practices that informed the plan for Fort Amsterdam.