“Loose Hogs, Fancy Dogs, and Mounds of Manure in the Streets of Manhattan”: An Interview with Catherine McNeur

Interviewed by Amanda Martin-Hardin, Maddy Aubey, and Prem Thakker of the Everyday Environmentalism Podcast

Today on the blog, Catherine McNeur discusses how during the early 19th century, working class New Yorkers living in Manhattan raised livestock and even practiced a form of recycling by reusing urban waste. Battles over urbanizing and beautifying New York City ensued, involving fights over sanitation and animals in the streets; and how to manage recurring epidemics and diseases like cholera that ravaged the city. McNeur explains how these tensions exacerbated early forms of gentrification in the 19th century, and contemplates how we can learn from the past to create more equitable urban green spaces and shared environmental resources in the future.

Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles and the Antebellum City

By Catherine McNeuir

Harvard University Press, 2017

320 pages

Where did you initially get the idea to write Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City?

I began it as a term paper in a grad class about the hog riots in New York. I had read a line in the book Gotham by Mike Wallace and William Burroughs about how there had been these hog riots, and it was just this short little paragraph that I was enchanted by. I was living in New York at the time, and the idea of pigs running in the streets was just hilarious to me. But then I was also intrigued by the idea that people were so passionate about their livestock that they would go out and riot to save them and keep them from being collected and sent to the pound. And so I started digging further into the pigs of the city, and really got into the project that way.

This environmental moment was showing the social tensions at that time between classes and between races. [It made me question] where else are these environmental battles either being amplified by social tensions or in turn amplifying them? So I started looking at New Yorkers complaining. That was really the search, and you know New Yorkers love to complain, right? It's just part of the culture. So [I started] looking at complaints in the government; people who sent petitions about various things; looking at complaints that were often anonymously written in newspapers about somebody having a terrible walk through the city, and just griping about how they ran into a pig or they had a goat bumping into them; or how a cow sidled up against the grocery and knocked over all these things. [I] just kind of [started] looking at these different incidents where people are complaining so much that it's like, something is being ruptured — some social contract is up in the air, and then they're trying to change the city, and think something's wrong with New York. Something needs to be changed. And so that was sort of a fertile moment to really investigate what's going on socially at that time.

In the book, you draw out a conflict between the countryside and urbanization in Manhattan. How was this tension specific to New York City?

Part of it is just how big Manhattan is and how many people were there. It was one of the most dense cities in terms of the island and [people were] really close up. So there's more people and they're creating more garbage and the garbage isn't getting collected. So, there's more animals who are able to thrive on this garbage. Because people were living in such close proximity to all these animals, and the city was changing rapidly (especially with the opening of the Erie Canal) and more people were moving into the city, there were just so many more moments of conflict and intersection with these animals that really erupted in this big way.

All these other cities had issues. So Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco — they had issues as well. But they often looked back to New York because New York's issues were much more extreme. And so, when New York was fighting over pigs on the streets and trying to come up with a law about that, San Francisco would mimic the law that's being written in New York to kind of nip that in the bud and not have that problem. I live in Portland, Oregon, and there's a law on the books here from 1851 about how no pigs are allowed on the streets. And it's clearly referencing what was happening in New York, because there wasn't nearly the kind of population here at that point to warrant a law yet, but they were just trying to make sure it was not going to be the same problem they were seeing on the East Coast.

Today when we think of streets, most people probably imagine concrete sidewalks and concrete streets with cars. However, what were streets physically like in 19th century New York City?

Yeah, so there were a number of paved streets or macadamized streets, especially in the denser part of New York. New Yorkers didn’t actually often know that they were paved because there was so much filth that was layered on top of it. There would be four to five inches of just animal manure that was right up on top of the pavement. So you could go your whole life and not know that New York streets are paved, because the manure and all the dirt and filth and garbage was all mixed in there. Not only was it smelly — and that was a major issue — but also it generated a lot of dust in the summer. So if it wasn't getting wetted it down often as horses would pound past on carriages it would generate all this dust that people would then breathe in and be repulsed by and think that that was causing a lot of their illnesses. It probably was aggravating their lungs, so there was often a lot of wetting the streets to keep everything down and not so dusty.

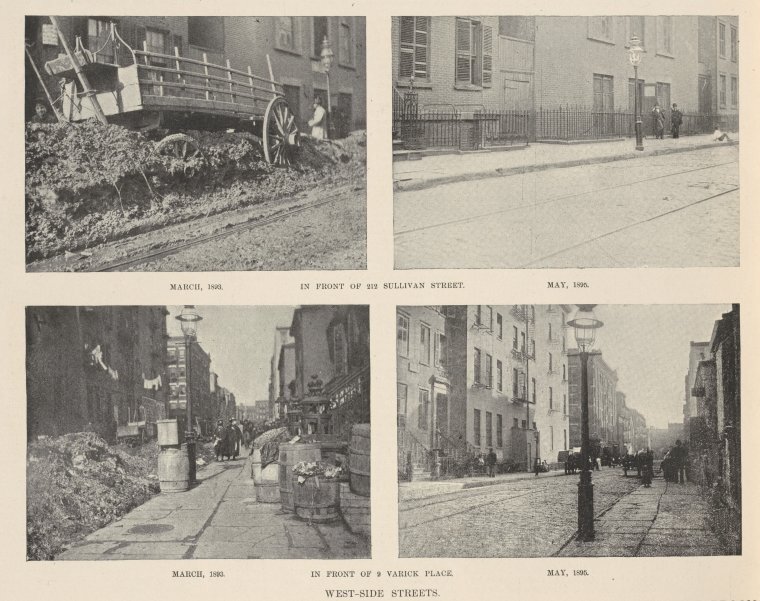

Once you get to the end of the 19th century and people were actually successful in cleaning the streets, it was sort of revolutionary! The before and after pictures are amazing. It was a major PR campaign for the city. They finally took control [of street sanitation] by the Progressive Era, but during this time period (the early 19th century) there's absolutely no control and it smells terrible. All of this manure was coming from a lot of animals because it was a horse-based city. Horses produced a lot of waste, but there were also pigs producing waste, and dogs too. Nobody was picking that stuff up. There's not a lot of garbage removal. So it's just a very smelly, but an organic smelly. I often suggest to my students that we're so used to smelling exhaust from cars, but that's perhaps much worse than having the smell of animals. That said, to our modern noses, it would be a really stinky place to be.

Before & after mages of cleaned streets (212 Sullivan Street and 9 Varick Place) in the 1890s Manhattan. Photograph from the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

How did the evolution of streets happen overall? When did we start seeing sidewalks as a specific space for pedestrians, as opposed to carriages or cars or things like that?

One of the things that I was researching was the promenades that people participated in. It was a kind of social promenading through different parts of the city. There was a promenade in Central Park that was created for this. There's also Battery Park, which was meant to be a promenade as well, and then Broadway served as a major promenade. It was like a social theater of walking the streets on certain sidewalks, sides of the street, tipping your hat to the people you respect, [or] ignoring the people you don't if they’re not dressed well. This is a major social liability, all of these issues. And then it's also hard to cross the street with all that filth! You know, you're all dressed up, you have to make your way across the street and not get your dress at all soiled with the horse manure and the pig waste. Or, you might bump up against the muddy pig, and then what is going to happen to you? So it's a really difficult thing. Then, I think it's cars, which is beyond my scope of my expertise. As cars really take off and more traffic accidents occur, that's when you see traffic lights and more sidewalk maintenance and watching out for pedestrians, let alone bikes and other vehicles on sidewalks or on streets.

Promenade in Central Park, New York, 1906. Photograph from the New York Public Library Digital Collections

In your book you use the phrase “urban commons,” which you define as resources like food waste or manure that enabled poor New Yorkers to eke out resources for survival and provided a small social safety net. What did the existence of the “urban commons” reveals about 19th century New York City?

The reason why the garbage was such a safety net is really because there was no other safety net. There was no welfare. There were soup kitchens in the city and an alms house to go to if you're extremely poor, but it's not enough to help. Those little programs were really just a tiny bandaid, especially as a huge number of impoverished Irish immigrants were coming into the city in the 1840s. But there was also a lot of people who were struggling for work at that time period, so the garbage was interesting because there was a lot that's in it that you can sell or reuse.

That’s something that really fascinates me about this. This was the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and we think of the Industrial Revolution as inherently wasteful, right? But a lot of these little industries were really building up on recycling a lot of the trash. So, even the night soil that I gestured to — people were really interested in harnessing whatever materials they had, whether it's their own waste, or an animal's waste, to sell it again and to use it again, and make sure that no nutrients are being lost in the rivers where all that stuff had been dumped. [People were] also using all the bones that were in the garbage to make various things like toothbrush handles or buttons, or grinding the bones to make a different kind of fertilizer. There were a lot of ways that the metals, rare as they were, could then be reused in various ways. [People salvaged] fabrics like woolens, and cotton and anything else that you could repurpose again. Ragpickers were often doing that: washing [rags] at home, hanging them up, and then selling them. People recycled a whole lot. But it speaks to the fact that there wasn't a lot of other safety nets for people that would catch them in poverty. And children were often employed and doing this--anybody could be employed by collecting garbage.

There are a lot of modern parallels. Now the can collectors are people who take advantage of the can deposits to make some money on the side. And you occasionally get a New York Times article highlighting how someone in Queens has put their child through college through collecting cans or something like that. That's really the closest modern equivalent to widespread rag picking and garbage picking.

Map of the New York City cholera epidemic, summer 1832 by David Meredith Reese. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

I wanted to ask about cholera, because it was a recurring devastating problem during 19th century New York City. So, what role have epidemics in the past played in terms of changing urban infrastructure? And how do some of these changes relate to streets in particular, or the urban environment more generally?

I've been thinking about this a lot in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. In the 19th century, what I saw with cholera was that it allowed for New York to push through what had been politically unpopular policies, like getting rid of the pigs, for instance, or enforcing a new sanitation program that was a lot more top down. All of this stuff that was almost impossible prior to the pandemic became possible. After people were panicking, thinking, "Are these pigs the reason why we're getting cholera?"

When the first cholera case in 1849 came out, the person who died was right next to a pig pen where they could smell the pig [from inside]. So, there were a lot of fingers being pointed at the pigs. So, people thought, "Maybe we should actually get rid of the pigs. Maybe this is the time when we can enforce this policy, and maybe we should [also] whitewash the tenement buildings." That was a top down level amount of government that had not existed before. People were not entering other people's apartments to whitewash in that way, or do other kinds of massive public health programming like that. So after pandemics, you see changes in public spaces in policies. It will be interesting to see what sticks that is happening right now. Will streets remain open for restaurants, but also for walking down the street and keeping social distance? Will there be more non-automobile streets in the future? I don't know, but it'll be interesting to see how it pans out.

Do you think there are historical parallels or lessons from the 19th century’s response to cholera that we could draw from to understand how this moment could offer a more equitable public health outcome, but also more equitable revisions of urban space?

Yeah, I think that having an eye towards the fact that there's going to be inequities [is important. Acknowledging that] there's going to be inequities about where the streets are that are getting closed down. [Is the street closure] just for elite dining that American Express is sponsoring, or is it being more broadly used? It's an important consideration for policymakers right now: to consider what's happening and what these changes are going forward, and how we can make this more equitable. You really got to the heart of it.

That's the major lesson to be learned from the 19th century, because there are people who lost a lot of their livelihoods because of these policies that came through. Just focusing in on the pigs — they weren't actually the source of cholera. They were kind of part and parcel with the sanitation issues in the city, and that was part of cholera. So in some ways, they're just swooped up with all of that. But people like Horace Greeley blamed the death of his child on the fact that his child lived near a lot of pigs. He saw that and so he trumpeted that through his newspaper. The result was inequities in the way that the environment was controlled, and so I think that that's going to be an issue again.

In terms of the formation and construction of urban streets, what are the competing interests that need to be dealt with? And are there through lines where you see the same problem that was happening in the 1800s are happening again, today?

I think at the heart of it, it's real estate. So, if you have an investment in real estate, whether in 1830s Greenwich Village or in 2021 up in the Upper West Side, you don't want a pig wandering the streets, or you don't want to have a homeless encampment along your street, because that's not going to help you when you go to sell your house or your apartment or whatever. And so, that's the gentrification that we were seeing in the 19th century. People were trying to beautify the city, but it was also gentrifying the spaces around them. And in turn, they controlled how people could use spaces, how their neighbors were able to make a living. It determined whether there was garbage on the street or not.

It's rough, there's a lot of really hard decisions that are made about sanitation. It was a public health issue, but it was also a gentrification issue if the garbage goes away. And then, there's an economic issue for the people who were left behind. And these were tough policy issues, although [wealthy] people didn't really lose too much sleep over it if they weren't losing their livelihoods themselves.

One of the lessons I would take from this 19th century story about New York and trying to apply it today is, when you see something that seems like an inarguable public good — like a bike lane or open streets for restaurants or for pedestrians or something like that — look at it really closely. Who is losing something in that process? In Portland, there was a story of a bike lane that was going up in a recently gentrifying neighborhood. Portland is growing and getting much more expensive very quickly. The bike lane went up, and the African American residents were really against the bike lane. All the kind of do-gooder city government workers were like, "Wait, what? We thought the bike lane was great. What's going on?" But it was like, well, who is this bike lane really for? Is this bike lane really to protect the folks who are living in a neighborhood already? Or is it to protect the hipsters moving into the neighborhood who want to ride down to their downtown jobs?

This interview is an edited excerpt of an audio interview with Dr. Catherine McNeur. Listen to the full recording here:

Catherine McNeur is Associate Professor of Environmental History and Public History at Portland State University. She is the award-winning author of Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City (Harvard University Press, 2014).

Amanda Martin-Hardin is a PhD candidate studying history at Columbia University. Her research focuses on how race & racism impact access to outdoor recreation spaces in the United States. You can learn more about her work here.

Maddy Aubey is a PhD student studying archaeology at UCLA. She is a NYC native. Her research interests focus on the African Diaspora in antebellum North America. She loves Nat Geo documentaries and anything related to goats.

Prem Thakker studies history at Columbia. He is from North Dakota (where every winter he and his buddies unite to build an annual friendship igloo). At school, Prem leads first-year students on four-day camp-and-bike orientation adventures. He is currently on a gap year, working at the American Prospect and authoring his newsletter, “better world."