It was a Vast and Fiendish Plot: The Confederate Attack on New York City

By Clint Johnson

An image of NYC looking south from St. Paul steeple. Everything to the south was to be destroyed in the attack.

The six Confederate officers who tried to burn down Manhattan on Friday night, November 25, 1864, were terrible terrorists. They were not terrible in the sense that they were religious fanatics intent on killing 814,000 people. They were terrible in the sense that they were warm-hearted men who wished no one harm. They were terrible in the sense that they had no idea how to burn down the nation’s largest city. They were not terrorists, just lousy spies and saboteurs.

None of the Confederates had ever visited New York before they arrived to burn it down. They did no scouting to find the most flammable targets. Just days before the attack, one of the Confederates was thrown out of his hotel for loudly proclaiming in his Alabama-born accent the merits of secession. None of the young men had any experience with incendiaries, yet they trusted a stranger to provide them 144 firebombs. When they took possession of the firebombs, they spent only a few minutes practicing with them—out in the open, in the daytime, in Central Park.

It was lucky for Manhattan these Confederates so thoroughly bungled their mission on November 25th. Had these six young men from Kentucky, Virginia, and Louisiana been more professional, New York City would have been in ashes on November 26th.

Even the planning for such a lofty goal as destroying The Emerald City (its nickname in 1864) was slipshod.

The Confederacy’s primary political goal in the summer of 1864 was creating a Northwest Confederacy from Indiana, Illinois and Ohio. While converting Illinois, the home state of President Abraham Lincoln, to the Confederate side sounds preposterous, The Confederacy was hopeful because the southern counties of Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana had retained strong Southern sympathies and had not voted for Lincoln in 1860.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis believed a second war front behind Northern lines was possible when he received secret, coded letters claiming as many as 490,000 Copperheads, the nickname of anti-Lincoln Democrats, were waiting in those states for someone with military skills to form them into an army.

Jacob Thompson, the Confederate Secret Service commissioner in Toronto who ordered the attack.

Acting on those letters, Davis set up The Confederate Secret Service under the command of former U.S. Congressman Jacob Thompson in the spring of 1864 to operate out of Toronto, Canada. The Canadian government did not care what Confederate agents did within its borders as long as no Canadian laws were violated. Several Confederates, who had been good battlefield spies, slipped across the Canadian border and traveled to Chicago, site of the September Democratic Party presidential convention. For several months the Confederate agents waited in anticipation of that Copperhead army arising to free 17,000 Confederate prisoners kept in camps at Camp Douglas, south of Chicago and in Rock Island, Illinois.

In the Confederacy’s view of a perfect world, this new army of freed Confederate soldiers and disgruntled civilian Midwesterners would force President Lincoln to pull his armies out of the South and reposition them in the Midwest. Meanwhile, the Democratic convention would nominate a sue-for-peace presidential candidate. That candidate would defeat Lincoln once a casualty-weary nation realized that the Confederacy was no longer contracting, and had opened a new front in the North.

That idea fell apart when no army of Copperheads arose. The Confederate agents literally sat in their hotel rooms all through August and September waiting for that army that never materialized.

The whole idea of a Northwest Confederacy and a Confederate army made up of dissatisfied Midwesterners was ridiculous. Had 490,000 Northern civilians actually formed a secret Confederate army, such a force would have been five times the size of the Union Army of the Potomac, and eight times the size of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in 1864. It was a fantastic pipe dream that Davis believed.

Unable to create a Northwest Confederacy, free the Confederate prisoners, or influence the Democratic presidential choice, the Confederate Secret Service turned to another lofty goal—disrupting Lincoln’s reelection on November 8th.

This new plan was just as bold; send agents back across the border to set fires on Election Day in Chicago, Cincinnati, Boston and New York City. The assumption was, like before, that the Union’s citizens would be so shocked and demoralized that the Confederacy could strike throughout the North in so many places simultaneously, that they would demand Lincoln—or Gen. George McClellan, his Democrat opponent for president—start peace negotiations.

It has been lost to history as to who ordered the attack on New York City. It may have been Thompson’s idea, or he may have followed an order from Jefferson Davis. What is known is that on October 15, 1864, an unusual editorial appeared in the Richmond Whig newspaper calling for Confederates to retaliate against Northern cities for the recent destruction of hundreds of farms in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. The editorial called on agents in Canada to “burn one of the chief cities of the enemy, say Boston, Philadelphia, or Cincinnati, and let its fate hang over the others as a warning of what may be done to them, if the present system of war on the part of the enemy is continued.” Later in the editorial there was a cryptic line discussing what would happen if the Federals retaliated against a Southern city such as Charleston or Richmond: “New York is worth twenty Richmonds.”

Two, young, but battle-experienced Confederate officers were put in command of the New York City operation. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Martin, 24, and Lieutenant John W. Headley, 24, both veteran officers under famed Kentucky cavalry General John Hunt Morgan, had been specifically ordered from Virginia to Canada to undertake whatever operations Thompson conceived. They were joined by six other Confederate officers, all of whom had escaped from Union prison camps before making their way into Canada. All but one of those men, Lieutenant Robert Cobb Kennedy, the oldest at 29, had also ridden with Morgan.

Eight Confederate officers, about to embark on the most ambitious secret mission of the war, apparently underwent no spy craft training while in Toronto. Headley, who wrote a 1905 book about his exploits, made no mention in his text of practicing in the open spaces of Canada with Greek fire, the spontaneously combustible chemical compound selected as the weapon to burn the city. They were told a contact would give them the chemical firebombs once they arrived in Manhattan.

The eight conspirators arrived in Manhattan early in November only to discover that newspapers were speculating on potential attacks from Canada. The Union general in charge of the city issued orders to be wary of outsiders in the city.

Nonplussed, the Confederates—all eight of them—strolled to the offices of their main contact, James McMaster, editor of the staunchly anti-Lincoln newspaper Freeman’s Journal, one of the few true national newspapers of the day. McMaster’s role in the plot was to activate yet another secret army of 25,000 Lincoln-hating New Yorkers who would raise the First National Flag of the Confederacy over New York City Hall once the fires had disrupted the election. McMaster’s office was a stone’s throw away from police headquarters.

Four days before Election Day, more than 3,500 Union troops arrived in the city, acting on at least two specific, accurate tips originating in Canada that Confederates would try to disrupt the elections by setting fires around the city. The Confederates postponed their plans and did what all out-of-towners do while visiting New York. They acted like tourists, taking in plays and seeing the sights until the Federal troops left town.

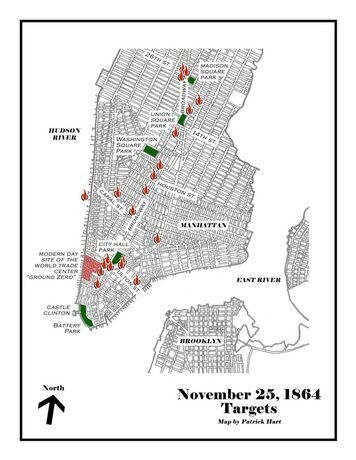

A map showing the targeted fires with some modern day landmarks.

What the Confederates did not do was explore Manhattan to find the most flammable targets. Had they done so, they would have found distilleries for camphene (a kind of fuel oil) and turpentine, more than a dozen lumber yards, and the biggest prize, the Manhattan Gas Works, all closely packed together in what is now the Meat Packing and Arts Districts. While the Manhattan Gas Works had a good safety record in 1864, explosions and fires at other coal-to-gas distilleries were common big city news stories.

With no more motivation than they were bored after spending three weeks in the city, the Confederates struck on the Friday after Thanksgiving. Weather forecasts and reports were not kept in those days, but no newspaper mentions of high winds suggest it was a calm night, hardly the conditions patient saboteurs would have chosen if they wanted western winds to spread flames from building to building.

Their weapons were 144 small vials of Greek fire obtained from an unnamed chemist living just west of Washington Square. The Confederates practiced with the vials by throwing them on boards outside a rented cottage in Central Park. Once the glass vials broke and the still-secret chemical compound was exposed to oxygen, flames erupted, setting fire to the boards. That satisfied the Confederates that the chemist had not double-crossed them, even though he risked his own life and home in any resulting conflagration.

Targets were more than 20 business hotels, most of them along Broadway with the furthest north being at 26th Street. Most were clustered around City Hall. The Confederates started setting fires on top of piles of clothing and furniture in their rooms at 8:00 p.m., reasoning that almost everyone staying in the hotels would be out on the town and not in any danger of being asleep in their rooms during a fire.

All of the fires either fizzled out on their own, or were discovered by hotel staff. The Greek fire never flamed up as it should have because the Confederates left their hotel windows closed, thus robbing the flames of a steady supply of oxygen.

There was some panic along Broadway as word of the attack spread. Shouts of “Fire!” coming from the LaFarge hotel disrupted the performance of Julius Caesar at the adjacent Winter Garden Theatre. It was the first time the famed acting family of the Booth brothers, Junius, Edwin and John Wilkes had ever been on stage in the same play.

Martin and Headley narrowly avoided capture the next day when they saw police officers questioning a young woman whose father was a secondary contact in the city. The Confederates lay low in their Central Park cottage until that Saturday night when all six who had set the fires (two men lost their nerve and did not participate) stealthily boarded a north-bound train. They made their way into Canada and were safely back in Toronto by Sunday.

The New York City newspapers expressed the city’s outrage over the attack. The New York Herald headlined it A Vast and Fiendish Plot while the New York Times correctly called it A Rebel Plot. The New York World kept a sense of humor and New Yorker pride by dismissing speculation that thieves had set the fires by proclaiming: “Do you suppose New York thieves would have bungled the business so stupidly?”

Had the Confederates left their windows open and struck early in the morning when the city’s volunteer fire fighters would have been asleep, there might have been disastrous results. Three times before the Confederate attack, in 1776, 1835, and 1846, Manhattan had experienced devastating fires that had burned significant parts of the city. All those fires started from a single source. All had overwhelmed the city’s volunteer fire department.

A sure disaster would have occurred if the Confederates had set 144 separate fires, all on the west side of the city, on a windy night, at all those choice targets of highly flammable lumber yards and fuel distilleries.

What if the conspirators had studied the properties of coal gas, then gained access to the Manhattan Gas Works? With technical knowledge gained from study in Toronto, they could have sabotaged the Gas Works’ water tanks used to regulate gas pressure. Without those critical water tanks in place, the gas pressure flowing through hundreds of miles of underground pipes into every neighborhood of Manhattan would have increased to dangerous levels. The Confederates might have figured out how to ignite all that flowing gas at the source.

Had those six Confederates not been such terrible terrorists, New York City would have burned to the ground on November 25, 1864.