Houses of Usher: Brief Surveys of a Failing Patch of Manhattan Now Known as the Upper East Side

By Michael Nichols

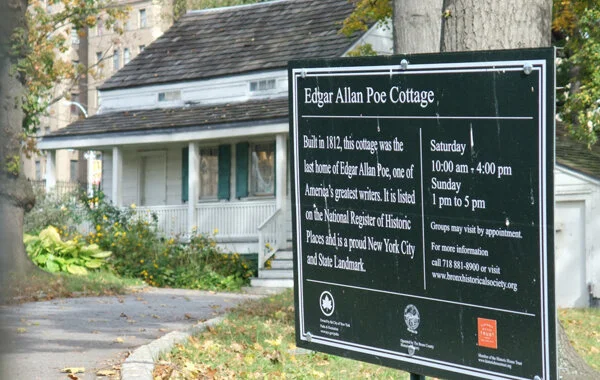

Edgar Allan Poe came to New York for what would be his last time in 1844, and busied himself with his writing, his magazines, and tending to his ailing wife Virginia. In less harried moments, he explored the city and its outskirts…roaming far and wide over this island of Mannahatta.

On the shores of the Hudson River, near the Brennan farm where he lived, he sat on rocky outcroppings brooding on the river and the blue Palisades on the other side. He strolled along the deck atop the massive Egyptian-like walls of the Distributing Reservoir on 42nd Street, watching the city below and beyond–and such vistas, too, in those days, from river to river and all the way downtown. He even found time to go rowing in the East River. He took stock of the city and reported what he saw in a weekly gossip column he called “Doings of Gotham” for the Columbia Spy, a small Pennsylvania newspaper.

On the eastern or “Sound” face of Mannahatta (why do we persist in de-euphonizing the true names?) are some of the most picturesque sites for villas to be found within the limits of Christendom. These localities, however, are neglected–unimproved. The old mansions upon them (principally wooden) are suffered to remain unrepaired, and present a melancholy spectacle of decrepitude. In fact, these magnificent places are doomed. The spirit of Improvement has withered them with its acrid breath. Streets are already “mapped” through them, and they are no longer suburban residences, but “town-lots. ” In some thirty years every noble cliff will be a pier, and the whole island will be densely desecrated by buildings of brick, with portentous facades of brown-stone, or brown-stonn, as the Gothamites have it.

–Doings of Gotham, May 14, 1844

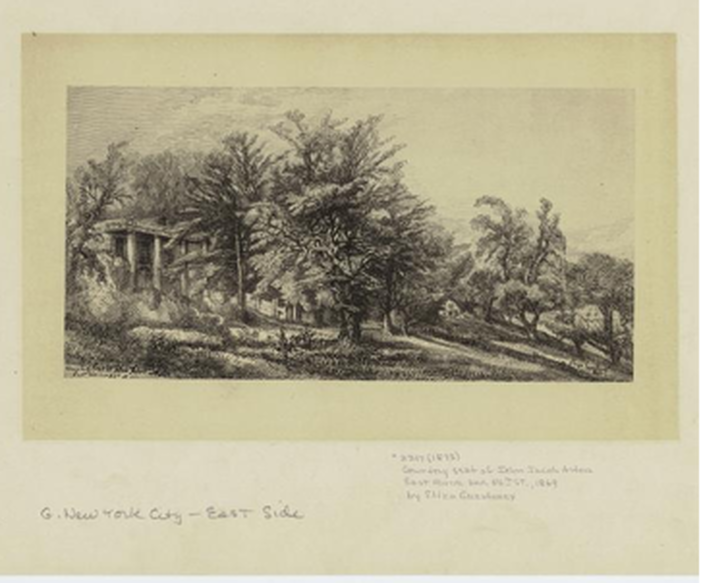

Eliza Greatorex: “Country seat of John Jacob Astor”

Poe wrote as if an outsider, which he was to New York, never quite taking the city into himself despite his having lived here off and on several times during his career–an outsider looking in for the benefit of his readers who were true outsiders. But he knew what he saw. Writing of the emerging city, Poe is remarkably prescient, although some things bear explaining.

By “suburban residences,” Poe means the country houses on the east side belonging to the Astors, the Beekmans, the Primes, the Rhinelanders, the Crugers, the Gracies, and other families–all names of the day, and all federated by business deals, dinner parties, and intermarriage.

By “mapped,” Poe is referring to Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, which laid out Manhattan in the gridiron pattern to which the city’s future growth would adhere. This far uptown, the grid still exists only on paper, and the map awaits its filling out with actual streets and avenues. But the inexorable uptown advance of the city pushes, and keeps pushing.

By “the spirit of improvement…with its acrid breath,” Poe means that nothing can be left alone.

Years before, in 1839, Poe had published “The Fall of the House of Usher” in which a man draws a house whose qualities are those of the doomed minds that inhabit it. Evidently the “melancholy spectacle of decrepitude” that certain houses present is not forgotten.

***

I looked upon the scene before me — upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain — upon the bleak walls — upon the vacant eye-like windows — upon a few rank sedges — and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees…

– House of Usher

…the sentience of vegetable things…

In the spring of 1869 the artist Eliza Pratt Greatorex visited this neighborhood with her papers and drawing pens. She was nearly 50 years old, her reputation as a landscape pen-and-ink artist still to be made. She would make it later, with sketches of Oberammergau, Italy, Colorado, and with the sketches she was now doing of New York City, including these neglected houses and cottages overlooking the East River.

By the time she got here the neighborhood was changing from rural to urban. The nearby village of Yorkville was growing into a middle-class suburb of merchants and bookkeepers, the airy new tenement buildings lining the crosstown streets a welcome relief from the cramped Lower East Side. But that was several blocks inland. Out here, the margin of Manhattan is still a vegetative world, and this is what Greatorex elects to capture. Like Poe, she sees a dying paradigm and what new one might be mapped in its place does not matter.

Every one of her drawings has this one thing in common: a house as the focal point, but so completely surrounded by vegetation that it is not the house that matters but the captivity of the house. Her drawings are like those of the 19th century explorer-artists who intended to describe exotic lands as precisely and scientifically as possible, but which today look nothing less than Romantic. Nowhere are people.

Not that people did not exist. While sketching the Astor house a curious bystander happened by, an old Scot, presumably a servant of the house. He spoke to her of the bygone days when Mr. Astor was still alive and how he maintained the good and pleasant fashions of the olden times. There were many servants in the house, and fires of blazing hickory were kept even in summer–a wise precaution against country chill and damp.

But now the hickory’s run out, or maybe just those who would tend the fire. In 1873, Mr. Astor’s house would be torn down. There was no point in letting it linger on, lest it fall and become part of the vegetation. Greatorex got there just in time.

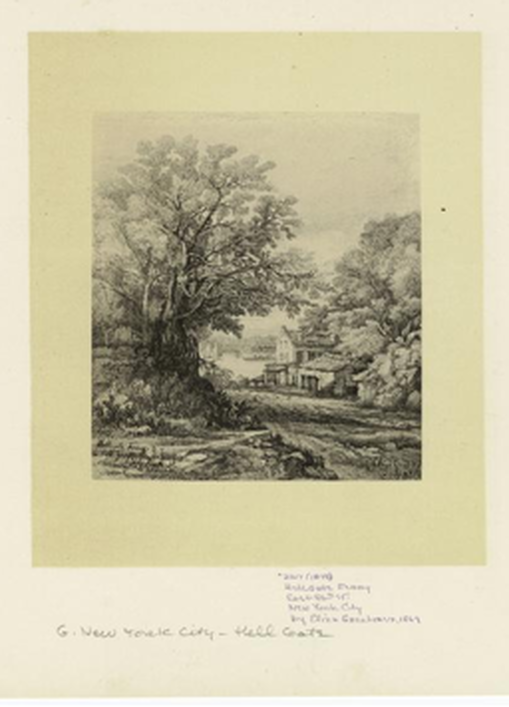

Eliza Greatorex: “Hell Gate Ferry Hotel”

Gracie Mansion

A story: Mister Mayor, says the real estate agent, I have the perfect house for you, a 19th century French chateaux. Note the mansard roof, the ornate accoutrements, very grand, befitting the mayor of the greatest city in the world, no? Answers Fiorello H. LaGuardia, the mayor of the people who talks up to President Roosevelt and who reads the funnies on the radio to children during the newspaper strike of 1945: What! Me in that? Wait, says the agent, I think we might have something more you, crosstown, on the East Side.

Mayors speak of budgets and let the furniture do the history. That Gracie Mansion, the official home to the Mayor of the City of New York, has survived this long can be credited to its being a shape-shifter. History knows Archibald Gracie more for his house than for him. He was hard-working, industrious, scrupulous, and successful until President Jefferson’s embargo in 1807. Thereafter, it was all downhill. To pay off his debts, Gracie sold the house in 1823 to Joseph Foulkes, who later sold it to Noah Wheaton whose family kept it until his death in 1896. The family sold it to the City of New York, and not knowing what to do with it, the City of New York allowed it to languish, but never to the point where it was beyond rescue. It served time, variously as an ice cream parlor, a public bathroom, and the Museum of the City of New York. In its rooms today are fine old Georgian furniture, paintings, carpets, and some cannon balls from the days when this site was a Revolutionary battlement.

Gracie wasn’t the first to build on this knoll. In 1770, Jacob Walton, built an elegant Georgian mansion on the site. Walton was from a prominent family. His grandfather William was a shipbuilder, known as Boss Walton, and also Captain, as he sailed his own ships to the West Indies and along the Spanish Main. Jacob’s generation was more settled, business-like, married to responsibility and good sense. With his brother, Jacob ran the largest insurance underwriting business in the city. He married well, to Polly Cruger, of the Cruger family, active in business and Loyalist politics. For a few years Walton lived in peace, but it was bad timing on his part to build his retreat just as a world war was breaking out. Strategists knew the place, too. General Washington, looking at the map, decided he needed this promontory, and as General Lee was in charge in these parts, Washington ordered Lee to take it. Which he did. Perhaps that Walton was a Loyalist made Lee’s job easier, perhaps it didn’t matter. The Waltons were expelled, and the house was turned into a bivouac for the rebels who were to man the redoubt down the hill. In September, 1776, the British fired at the redoubt from across the river, at Hallett’s Point. Their missiles also hit the Loyalist’s house, burning it to its foundation. Walton had dug a tunnel from his house down to the river’s edge, an escape hatch, which unfortunately he could not escape to in time. It was found decades later by workers on the grounds of Gracie Mansion, the mayor’s house.

Strange that mayors, who can get away with saying My city, never say it. It is always Our city, with that careful inclusion of the body politick. But I’ll bet more than one mayor has stepped out onto the yard of this citified country house on some languorous summer evening—and smelling the sea, and taking in the view of the wide Hell Gate, the twinkling lights of the bridges, the great buildings up river and down, the barges plying the water, the gulls, the sky framed by a stand of oak and London plane, the evening’s descent—I’ll bet more than one mayor has said to himself, My city.

***

Hell Gate Ferry Hotel

Shaking off from my spirit what must have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building. Its principal feature seemed to be that of an excessive antiquity. The discoloration of ages had been great. In this there was much that reminded me of the specious totality of old woodwork which has rotted for years in some neglected vault, with no disturbance from the breath of the external air.

–House of Usher

Again her timing is perfect. Eliza situates herself somewhere near Avenue B, now East End Avenue, but then hardly an avenue at all, and looks down a rutted East 86th Street toward the East River. From that perspective, the arching branches of trees and the rock walls create a kind of gyred tunnel. At the end, in a small space of light, is the Hell Gate Ferry Hotel. In its day, about 20 years before, when it was run by a Mr. Dunlop, the place was something of a resort, if Dunlop’s advertising can be believed: “An obliging host, beautiful summer retreat, refreshments of the first quality with horses and pleasure wagons to let. Also, boats and tackle for fishing, renders this spot second to none in the vicinity of New York City. Murphy’s stage, every fifteen minutes to City Hall, for six cents.”

But when Greatorex arrives, well, there’s not much activity for a hotel. In fact, it seems a ruin, about the oldest house come upon yet. It is built of heavy stone, its sills and ledges of lighter brownstone. Inside, the place gives the appearance of a once comfortable dwelling, roomy, with small panes of glass set in windows and doors. A rambling balcony remains, affording a wide view of the river, if one can trust to step out on it. Should travelers come by wanting to summon the ferry, they need only alert the ferryman by blowing through a conch shell.

Yet traces of this topography remain, the scene is vaguely familiar today. The cut Greatorex depicts still exists, though widened and fashioned into an arcade of cherry blossom trees and bluestone walks, and now ending not at the river but at the embankment built in 1940 to cover the FDR Drive that skirts the river. A garden has been planted in the embankment and a double-staircase framing the garden leads to the promenade above. But what defines this place now is what defined it then: the walls of Manhattan schist and the London planes and elm trees that enclose the arcade on both sides. The massive blocks of schist are weathered and worn, their fissures and faults overcome with new growth of snakeroot and moss–a reminder that what the earth tosses up is not to be completely obliterated. And so it remains today, the cut done up a little more formally, but as out of the way and ancient now as it was then, in Poe’s phrase…with no disturbance from the breath of the external air…which down here means the din and trouble of the city.

Michael Nichols lives in New York City and is an ardent scavenger of city lore and other historical curiosities. His first contribution to the Blotter was “An Afternoon at Blackwell’s Light.”

Sources

Eliza Greatorex, M. Despard. Old New York: From the Battery to Bloomingdale (Vol II). New York, 1875.

Edgar Allan Poe. “Doings of Gotham.” Columbia Spy, 1844.

Joseph Scoville. The Old Merchants of New York City (Vol I). New York, 1870.

Mike Wallace & Edwin G. Burrows. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York, 1999.

Anthony Lofaso. Origins and History of the Village of Yorkville in the City of New York. New York, 1972.

John Austin Stevens, et al. The Magazine of American History. New York, 1879.

All images are courtesy of The New York Public Library. www.nypl.org