Sheila Gerami, The Hall of Fame for Great Americans: A Biography of Stanford White’s Forgotten Memorial

Reviewed By Paul Ranogajec

The Hall of Fame for Great Americans, a group memorial and patriotic monument on the campus of the Bronx Community College, is a rich site for interrogating a range of cultural and political questions about American society from the 1890s to the present. Sheila Gerami’s book brings the now obscure monument to the attention of art historians and others who might want to approach New York’s memorial landscape from new angles. The book presents the results of significant new research and interpretive analysis. Surprisingly, Gerami eschews art-historical methods and instead provides an institutional history of the monument. While the book should be considered a starting point only, it succeeds at opening a new avenue for research.

On Memorial Day in 1901, New York University (NYU) Chancellor Henry Mitchell McCracken inaugurated the Hall of Fame for Great Americans at the school’s new Bronx campus. Located in Fordham Heights, uphill from the Harlem River and directly east of Manhattan’s Fort Tryon Park, the campus was then at the outskirts of the city. In its early years, visitors to the Hall of Fame would have felt as if they were leaving the city and entering a suburban retreat. To visit was to undertake a pilgrimage to a shrine of national heroes.

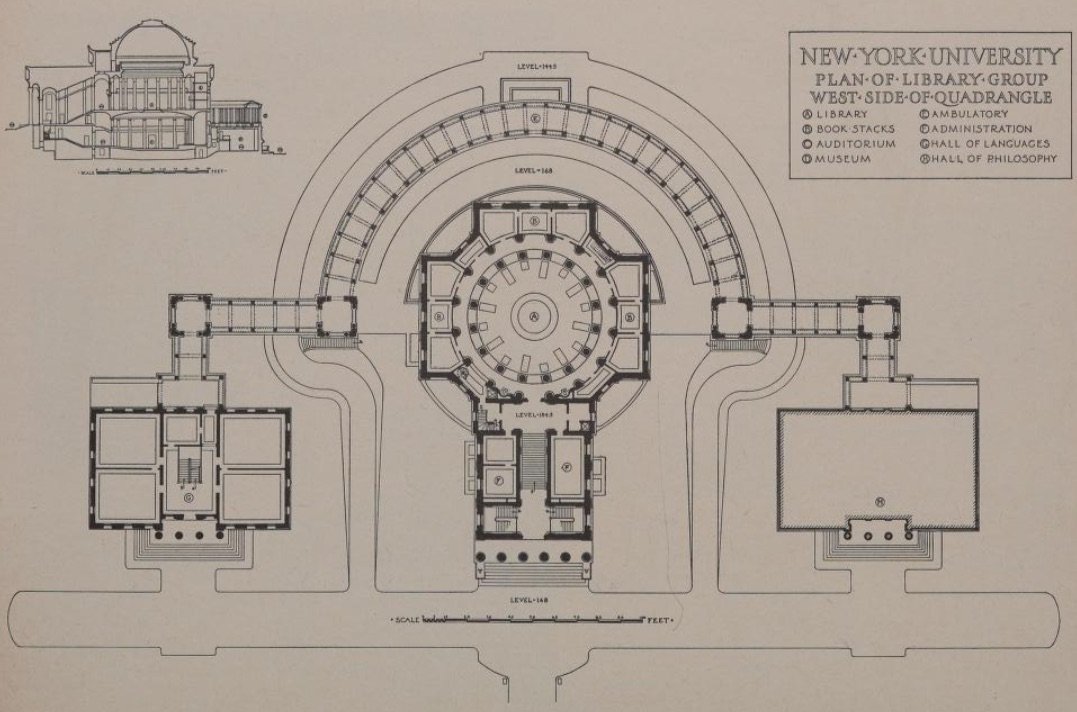

Designs for NYU’s Bronx campus were initiated in 1892 by Stanford White, a partner in the celebrated architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White. Only a few months later, under the direction of Charles McKim, the firm also became engaged in designing the new uptown campus of Columbia University. In the end, both campuses received a domed library as the focal point of a spacious plaza enclosed by free-standing buildings. These similar designs in part reflect the architects’ knowledge of prestigious precedents such as Thomas Jefferson’s “Academical Village,” the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. A Roman Pantheon-like monument of learning thus unites the three campuses.

As Gerami emphasizes, NYU’s Bronx campus design resulted from a close collaboration between McCracken and White. It was McCracken who dreamed up the idea of a Hall of Fame to occupy the colonnade behind the library. A key formal element in White’s plan from nearly the beginning, the colonnade was originally an ornamental ambulatory to prettify the edge of the bluff and provide a campus outlook to take advantage of panoramic views across the Hudson River. With McCracken’s proposal for the Hall of Fame, new funding was assured to allow completion of White’s plan. The first honoree election was held in 1900 and the Hall’s inauguration was celebrated the next year.

Plan of the campus of New York University (now Bronx Community College), from A Monograph of the Work of McKim, Mead & White, 1915.

Strangely missing from all descriptions of White’s campus plan and of the Hall of Fame that I am aware of—including Gerami’s book—is one small but important difference between the projected plan and the built version. As published in the 1915 official compilation of the firm’s work, A Monograph of the Work of McKim, Mead & White (above), the plan shows a symmetrical colonnaded ambulatory in three parts on the west side of Gould Library. The main part is the central half-circle to which are attached lateral wings. These wings connect to the academic buildings flanking the library. As the aerial view (below) shows, there is an extension of the colonnade to the north: it runs past what was originally the Hall of Philosophy (not built until 1912, according to Gerami). Presumably the extended wing was added after construction of the building, but no architectural descriptions mention it.

Aerial view of the campus of Bronx Community College, formerly New York University. From Google Maps, 2024.

The extension has an important impact on the Hall of Fame: it provides the memorial with a visible starting (or ending) point. Originally, entrance points into the colonnade were ambiguous. Four connecting pavilions mark points where the colonnade changes direction. Informally, entrances/exits occur where the colonnade is attached to the backs of the academic buildings. Yet, as an architectural type, the ambulatory suggests no privileged direction of movement, no necessary starting and ending points. While the extension interrupts the plan’s symmetry, this is not very evident to the casual visitor. The addition gives the memorial a clearer visual identity and sense of completeness compared to the original plan, where the structure appears as a scenic addition to the academic buildings rather than a complete element on its own.

View of the colonnade extension at the Hall of Fame. From Google Maps, 2024.

This overlooked detail points to my first criticism of the book. In using the phrase “Stanford White’s memorial” in the subtitle, the reader is led to expect more consideration of White and the architectural design. The wording puts the book in the orbit of architectural history rather than of institutional history. Yet White’s role is dispensed quickly at the beginning.

There is also a rather compressed description of the architectural design. In fact, the text spends more time on the design’s precursors—the Parisian Panthéon, the Temple of British Worthies at Stowe Garden, and National Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol, for instance—than on White’s design. No ground plan is illustrated, and the photographs, mostly of middling quality, fail to adequately convey the spatial complexity of the hemicycle design, its relationship to the library, or a sense of how a visitor moves through the colonnade. Absence of a ground plan proves a detriment to understanding the memorial as a piece of architecture.

Ater the introductory chapter documenting White’s design and McCracken’s institutional establishment of the Hall of Fame, the book focuses on the achievements of the honorees and the mechanisms, publicity, and politics of the selection process. As an institutional history, the book centers on the personalities and hero-status of the Hall’s honorees. The memorial fades away as a material art and architectural object which the public engages in a physical encounter as part of a special pilgrimage. Gerami justifies her turn away from art-historical questions by suggesting the individual sculptures are uninteresting in themselves: “Removed from their site and from the historical context that gave rise to them, the busts themselves, larger-than-life bronzes created in the academic style of their day, would be nowhere near as captivating as the ensemble they form. Thus, stylistic analysis of the bronzes as sculptural objects plays only a minor role in my research.”

Tracing its history this way unintentionally extends the historiographical grip of the Great Man Theory which Gerami argues underlies the founding and meaning of the Hall of Fame itself. An undeniably important element in nineteenth-century historiography, Great Man Theory helps make sense of the biographical component of the memorial. But Gerami’s framing misses something larger. Reporting on the memorial’s inaugural ceremony in 1901, the Brooklyn Eagle declared, “We have really a national Hall of Fame. The true winnowing of the temporary to the permanent in the achievement of our people has well begun. As it goes on, decade by decade, this colonnade of University Heights will become more and more a national landmark.” Such rhetoric points to the importance of nationalist ideology and its intersection with the international memorial tradition of the nineteenth century. [1]

Considering the larger political context, Great Man Theory itself was buoyed by the ideological support of nationalism. In turn-of-the-twentieth-century liberal culture there was a view that each nation had its own identity, traditions, and heroes. Seen in this light, the Hall of Fame’s historical paradox comes into view: while Great Man Theory focuses attention on individuals’ heroic accomplishments and iconic personalities, the memorial functions—and physically appears—as a portrait ensemble of greats subordinated to a collective image of wholeness and unity. Based in individual achievement and intended to inspire patriotism, this was a celebration of American cultural identity. Great Man Theory was in this sense a secondary impetus behind the memorial’s creation: the heroes are representatives of a single nation, after all. They were, at least until the 1960s, considered avatars of widely shared American virtues.

Along with Great Man Theory, the choice to focus on the mechanisms of the selection process and on providing capsule biographies of the honorees pushes the book’s analysis away from society. Wherever Gerami moves outside this framework, as in the chapter on the advocacy and patronage of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), or in the later sections dealing with questions of public archives, didactic functions, and race and representation, the reader encounters the most compelling and lively text. Indeed, Gerami’s look at the UDC provides keen insights into the larger significance of the Hall of Fame. As she argues, the UDC’s efforts to include Confederate figures were more about vindication of the Lost Cause movement than about memorialization of historically significant Southern leaders.

The Hall of Fame for Great Americans at Bronx Community College. Photograph, 2010. Image in the public domain. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The book illustrates most of the honorees with portrait photographs or other artworks rather than showing the busts that line the memorial. It could have been a both-and situation. This approach obviously follows from the author’s contention that the individual busts are themselves unremarkable artworks. But ignoring the individual pieces, coupled with the lack of quality photographs of the structure overall, makes it hard for the reader to judge the monument as a whole.

According to Gerami, popular participation in the selection process made it democratic. This loaded term offers an occasion to interrogate questions of access, funding, propaganda functions, and the conditions of genuine democratic participation in public art and public spaces. [2] However, Gerami seems to accept the memorial promoters’ assertions of its democratic credentials despite the heavy mediation of public participation through several layers of elite filtering established by McCracken. A 2019 essay (here at Gotham) by Cynthia Tobar, uncited by Gerami, points to how a more critical engagement with the question of participation at the Hall of Fame might show “the limits to its democratic vision when curated by a powerful and privileged elite.” [3]

As Gerami’s book demonstrates, a single memorial can elicit an array of questions and approaches by scholars. With steady attention now being given to the architecture and monuments of New York from the decades around 1900, a better sense of the complex and conflicted significance of these often-neglected works is beginning to emerge. Despite some shortcomings, it is good to have Gerami’s book as a pointer for subsequent research. If it helps inspire richer life histories of New York’s monuments, that will be something to cheer.

Paul Ranogajec is an architectural historian in London with a Ph.D. in art history from the CUNY Graduate Center. He is completing a book on scenography and politics in New York’s Beaux-Arts architecture.

For disclosure, the author and I participated in a small Americanist discussion salon for a short period in 2014-16, where this study was once previewed. I also provided a brief note on architectural terminology in response to the author’s query. My name therefore appears in the acknowledgments.

[1] On this tradition, see Sergiusz Michalski, Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage, 1870-1997 (London: Reaktion Books, 1998).

[2] Some models treating New York topics are Michelle H. Bogart, Public Sculpture and the Civic Ideal in New York City, 1890-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989); Rosalyn Deutsche, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996); and Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, Design for the Crowd: Patriotism and Protest in Union Square (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019).

[3] Cynthia Tobar, “Inclusive Archiving, Public Art, and Representation at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans,” Gotham, July 18, 2019. Three other important secondary studies do not appear in the book’s bibliography: Kate Culkin, “A Bridge, Not a Wall: Uses of The Hall of Fame for Great Americans at Bronx Community College,” in Remaking the American College Campus: Essays, ed. Jonathan Silverman and Meghan M. Sweeney (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016), 57-78; Kate Culkin, “Advocacy and Memory at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans,” Gotham, March 27, 2018; and Evan J. Friss, “From University Heights to Cooperstown: Halls of Fame and American Memory,” Journal of Archival Organization 3, no. 4 (2006): 87-104.