Grassroots Anti-Crack Activism in the Northwest Bronx

By Noël K. Wolfe

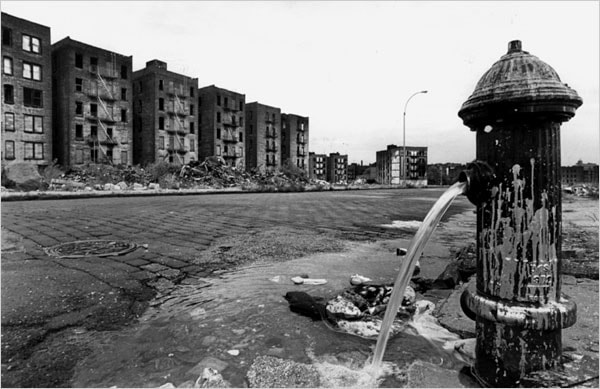

Charlotte Street in the South Bronx. Neal Boenzi/New York Times, 1975

President Carter visits in 1977

Ronald Reagan campaign-stops in August 1980. Presidential candidate Jesse Jackson would visit in 1984, and President Clinton in 1997.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Bronx was a national symbol of urban decay, used as a political backdrop to send messages of despair, governmental failure, the decline of urban spaces and other racialized messages of fear.[1] Drug addiction and drug selling became a national, state, and local political battleground that reflected differing political ideologies. Even at the community level, a tension existed within New York City neighborhoods about how best to respond to drug crises. In 1969, New York Black Panther Party member Michael “Cetewayo” Tabor warned Harlemites about the long-term implications of inviting police, who he described as “alien hostile troops,” into their community to address heroin addiction and drug-related crime. While Tabor did not deny that those addicted to heroin were committing “most of their robberies, burglaries and thefts in the Black community against Black people,” he challenged community members to be suspicious of the motives behind “placing more pigs in the ghetto.”[2] Tabor sought a community-driven solution to heroin addiction — one that did not include the police. Similarly in the Bronx, members of the Young Lords Party responded to heroin addiction by occupying the administrative offices of Lincoln Hospital in November 1970 and successfully demanding a drug treatment program for community members. The Lincoln Hospital Detox Program, a “community-worker controlled program,” paired political education with therapeutic support to assist those seeking help to overcome addiction.[3]

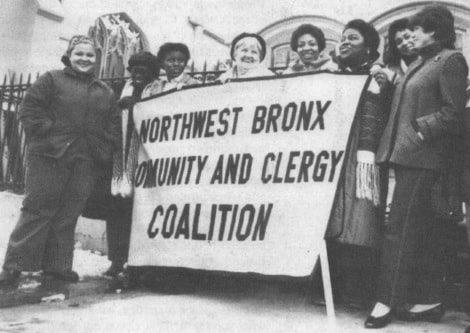

Even as the Panthers and the Young Lords called for a treatment and education-based response to heroin, other African-American Harlemites used “tough-on-crime” rhetoric to demand a legislative and policing response to drugs in their neighborhoods.[4] These demands reflected a larger shift in political rhetoric and action in response to drugs — one that characterized rehabilitative efforts as failed and “punitive efforts as inevitable.”[5] It was within this political context that a new grassroots organization, the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition (NWBCCC), officially formed with a mission to “stabilize and improve the quality of life for all residents of the Northwest Bronx.”[6] In less than a decade, the organization would shift its focus to address the increasing visibility of crack cocaine in its members’ neighborhoods. The Coalition’s strategic choices reflected the tension between public health and punitive responses to addiction and drug selling, the law and order political climate, and activists’ fears of a growing drug crisis. While the Coalition initially adopted a blended (albeit unbalanced) strategic response to crack selling and addiction, it was the punitive response that eventually received the most traction and support from New York City politicians. Yet, within just a few years of initiating its anti-drug activism, the Coalition shifted away from demanding a primarily punitive response to drug selling and focused instead on how best to divert youth from addiction and the drug economy. This marked a clear departure from the federal government’s antidrug position as well as a sharp contrast to the broken windows policing initiatives adopted in the 1990s by Rudy Giuliani.

Years before crack became a national media obsession, multiracial, faith-based activists in the Bronx took direct action against young black and Latino drug sellers and users in their shared neighborhoods. As early as 1983, Coalition members began prioritizing anti-drug activism in order to address the rise of crack cocaine. They met with police officials and demanded more police in Northwest Bronx neighborhoods, targeted drug sweeps, prosecution of landlords who failed to evict drug-selling tenants, and the establishment of a specialized drug court.[7] By 1985, this shift was reflected throughout the broader organization. During the height of its anti-crack activism, the Coalition had approximately 10,000 members.[8] Coalition members brought visibility to the crisis in their neighborhoods and pressure to bear on New York politicians through direct action campaigns. They courted media coverage of their activities and demands in order to raise awareness of the crisis in the Bronx and to hold local politicians and police accountable for a response. Activists met Mayor Edward Koch, the New York Attorney General and partnered with New York’s Catholic hierarchy who wielded significant political influence. When they were ignored, activists marched, picketed, and publicly shamed political figures until they agreed to help. At its broadest, the Coalition conceived of an anti-drug strategy that addressed education and rehabilitation, yet, their earliest and most sustained demands were for a punitive, criminal justice response to crack cocaine in their neighborhoods.

Direct action campaigns took several forms, including marches, rallies, demonstrations and direct intervention at drug marketplaces. One coalition leader explained that marches served two purposes. First, activists used direct action to generate media and political attention to their cause with the hope of gaining greater political and policing support. Second, activists wanted to make a public demonstration to show community members that some of their neighbors were fighting back and encourage greater community participation in anti-crack activism.[9] In September 1984, the NWBCCC Crime and Security Committee called on community members to join them in a meeting with Bronx Borough Commander John McCabe to demand more police patrolling their streets in order to address the pervasiveness of drugs in their neighborhoods.[10] Later that month, Committee members met to establish a follow-up plan from the meeting with McCabe. Their meeting agenda included pinpointing “hot spots,” areas of increased criminal activity, identifying priority spots where the community wanted increased foot patrols and scheduling a meeting with Police Commissioner Ben Ward.[11]

St. Athanasia's baseball team. Credit: Mel Rosenthal

Teenagers cleaning up rubble in order to create a neighborhood garden. 1976-82. Credit: Mel Rosenthal

Mother and daughter outside their home. Credit: Mel Rosenthal

On February 2, 1985, the Coalition touted a victory: foot patrols in a handful of Northwest Bronx neighborhoods — Fordham Bedford, Bedford Park and Mosholu Woodlawn — all located within the 52nd precinct.[12] For nearly two years, the Coalition lobbied the NYPD for foot patrols in order to address “quality of life problems” that had become more prevalent with the increase in illegal drugs.[13] Coalition leaders circulated precinct maps, foot patrol locations and the names of police officers assigned to walk the beat in Northwest Bronx neighborhoods. Activists wanted community members to personalize their interactions with community patrol officers. Coalition members sought to create partnerships with local police and local precincts in order to combat crime in their community.[14]

In mid-February 1985, members of the Coalition-affiliated Mount Hope Organization demonstrated outside of the NYPD’s 46th Precinct on Ryer Avenue in the West Bronx. Newspaper coverage of the march described activists as “frustrated, angered and outraged” over the dangers associated with the drug trade and the police department’s failure to effectively address the problem.[15] This frustration motivated community members and parishioners from St. Edmund’s Episcopal Church, St. Thomas Lutheran, St. Margaret Mary’s Roman Catholic Church and the Iglesia Mission to picket the 46th precinct. They stated that in just one building on Walton and Burnside Avenues a man was making $30,000 dollars per day selling cocaine, and on Morris and Davidson Avenues young men were walking the streets brandishing weapons. The demonstrators were seeking a daily police presence at known drug hotspots in order to deter drug sellers. The police also appeared frustrated. While they identified hotspots within the 46th and 52nd precincts where they performed special drug sweeps, the police complained that short jail sentences, small fines and the lucrative nature of the drug economy meant that their policing activities were making little impact.[16]

Coalition members also included the courts as part of their anti-drug strategy. During the same month that activists celebrated winning foot patrols for certain neighborhoods, they also strategized how to maximize the court system’s effectiveness in handling drug cases.[17] This process began with the Coalition Planning Committee developing four points for activism to present at a meeting with the Chairman of the New York State Assembly’s Code Committee, George Friedman. The Committee’s four activism points included: enhanced misdemeanors for drug crimes, judge-directed voir dire of prospective jurors, the right to sue criminals for their property, and an extension of the district attorney’s power to appeal sentencing decisions.[18]

At the center of Coalition activists’ demands was a call for parity in policing resources — Bronx activists wanted the same elite anti-drug initiatives used in Manhattan to also be put in place in the Bronx. The Coalition targeted Police Commissioner Ben Ward for his failure to implement an “Operation Pressure Point” in the Bronx.[19] The demand for an “Operation Pressure Point” was one of four demands in the Coalition’s “Taking Back Our Streets” Campaign. These demands were introduced publicly during the Coalition’s largest direct action event of 1985.

On June 29th 1985, the Coalition rallied approximately 1,500 members to march down Fordham Road demanding help in their war against drugs. This was a unified multi-association demonstration that brought massive visibility to the Coalition’s anti-drug agenda. Residents started from seven different Bronx neighborhoods and moved towards a central gathering place, Poe Park. Residents converged on the Grand Concourse — the main shopping district in the Bronx–and blockaded the main intersection for over an hour. The president of the coalition spoke out and said “for every junkie and dealer, there are 1000 good people doing the right thing, trying to make a decent living for themselves and their kids, trying to make their neighborhoods better places. That’s why we’re here today — to send a message to Police Commissioner Ward and to City Hall that we’re staying, and drugs must go.”[20] It was during this massive rally that the Coalition outlined their four demands for ending the drug crisis in their community. First, they wanted the city to assign an elite narcotics task force to their neighborhood and place experienced police on the street. Next, activists wanted to deem certain areas in the Bronx under temporary federal jurisdiction so that drug sellers arrested in those zones would be tried in federal courts. Lastly, activists wanted a face-to-face meeting with New York Police Commissioner Ben Ward to outline a plan of action and demand police accountability.[21]

The New York Daily News covered the demonstration and printed activists’ demands in the paper, further extending the reach of the march.[22] This demonstration was one of nearly a hundred or more that would occur before activists’ demands were met. From 1983 through 1986, the Coalition’s anti-drug strategy focused primarily on enlisting the support of the NYPD for a punitive response to drug sellers in their neighborhoods, direct action campaigns to dislodge drug sellers from drug marketplaces and pressure the NYPD for support, and lastly, creating powerful allies who could provide resources and legislative support. Activists believed that “attacking the drug marketplace and reclaiming those [drug selling] locations with positive activity” was necessary to help stabilize the community.[23] While Coalition activists also wanted to provide drug-free spaces with peer counseling and rehabilitative services, as well as activism, education and employment opportunities for youth, these elements were not the focus of its anti-drug activities between 1983 and 1986.[24]

1987 was a watershed year for the Coalition’s war against drugs. While the organization continued to place significant emphasis on policing interventions, the Coalition also began to broaden its anti-drug strategy. The organization expanded its focus on youth, which included youth-led activism and education initiatives. The Coalition also renewed its focus on housing. It saw affordable and livable housing as an important element of community revitalization but also as a part of a larger anti-drug strategy. Coalition associations formed partnerships with local precincts to effect noticeable change in local drug marketplaces, including displacing drug sellers from apartment buildings. Coalition leaders also continued to demand that the NYPD support broader anti-drug initiatives in the Bronx. During 1987, however, the Coalition transitioned from being ignored by public officials to spearheading a multi-agency effort against crack in the Bronx that included federal prosecutors, district attorneys and other state and local officials — however, it took them years to reach that point.

Following the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, the anti-crack strategies of Bronx activists and federal politicians diverged. Federal political strategy against crack remained primarily punitive and with the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, Congress increasingly targeted drug users. After 1987, Bronx activists, however, shifted to more comprehensive and locally-focused anti-drug strategies. The Coalition sought to address larger systemic issues that they identified as underlying the crack crisis. The organizations adopted initiatives to address lack of adequate housing, education, and employment opportunities, particularly for youth. They also sought addiction prevention and rehabilitation services. By 1987, the Coalition began implementing the broader anti-drug plan that it had first conceived in 1985. It sought to divert teenagers from the crack economy by providing youth-related services, after-school centers, support for parents of at-risk youth, education and job training programs, as well as opportunities for youth activism and socializing. The Coalition continued to seek partnerships with local police precincts and increased anti-drug policing in their neighborhoods. However, the Coalition also called for police accountability, investigation into police abuse against Bronx residents of color, and specifically demanded training for police officers to curb racialized and increasingly abusive police conduct. Just as the Coalition was at the forefront of recognizing the crisis that crack presented in the Bronx, it also experienced the damaging effects of overbroad and racialized policing.

Northwest Bronx activists’ response to crack cocaine was influenced by a number of factors. Activists viewed crack, particularly because of the violence associated with the crack trade, as a destabilizing community crisis and they engaged in crisis management decision-making. They initially targeted crack sellers to remove the immediate threat before focusing on drug prevention, education and rehabilitation initiatives. Activists were impacted by the larger legal and political climate of the War on Drugs and embraced a normalized rhetoric of war. Bronx anti-crack activism was limited by cuts to social programs that had provided support for education, rehabilitation, afterschool programs, and a number of other programs that working-class and poor communities used to support neighborhood youth. Religious faith also impacted grassroots activism. Christian faith allowed activists to find common ground in racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods. Activists understood crack as both a secular and moral crisis and their response to the drug was influenced by a perceived moral obligation to lessen suffering in their community, as well as the practical concern for their safety and the safety of loved ones.

Yet, even as activists feared crack-related violence and felt a growing distance between community elders and youth, they first conceptualized a policing intervention as a targeted initial response to a growing crisis. They hoped to clear the streets so that they could establish education and job programs and build youth centers; they wanted to provide community youth with immediate alternatives to the drug trade, as well as pathways for long-term economic success. Coalition members did not envision a police state in their neighborhoods. Rather, they sought a community-police collaboration where both residents and police officers were stakeholders working towards a safe community where all of its members could thrive — a goal that grassroots community activist organizations continue to strive towards today. Without critical funding to support community revitalization, local organizations will find themselves facing the same limited choices as the Coalition in the 1980s and 1990s — with funds to support law-enforcement efforts but little else.

Noël Wolfe is the Helen and Agnes Ainsworth Visiting Assistant Professor of American Culture at Randolph College. Her current scholarship explores how the arrival of crack cocaine shaped a generational conflict among Bronx residents and impacted grassroots activism.

Notes

[1] For example, President Carter wanted to know what could be “salvaged” during his 1977 visit to the South Bronx (Lee Dembart, “Carter Takes ‘Sobering’ Trip to South Bronx: Carter Finds Hope Amid Blight on ‘Sobering’ Trip to Bronx,” New York Times, October 6, 1977). Three years later, presidential candidate Ronald Reagan described the same neighborhood as similar to “London after the blitz” (“Reagan, in South Bronx, Says Carter Broke Vow: Raises Voice Above Chants,” New York Times, August 6, 1980). For a fuller account of the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition’s anti-crack tactics can be found at Noël K. Wolfe, “Battling Crack: A Study of the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition’s Tactics,” Journal of Urban History 43, no. 1 (2017): 18-32.

[2] Michael “Cetewayo” Tabor, “Capitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide,” pamphlet, circa 1969.

[3] Young Lords Party, “Fight Drugs – To Survive,” Palante, 3 no. 14 (1971): 7, Young Lords Party Collection, Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library and Archives, Hunter College, CUNY.

[4] See Michael Javen Fortner, Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

[5] Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, “Guns and Butter: The Welfare State, the Carceral State, and the Politics of Exclusion in the Postwar United States,” Journal of American History, 102, no. 1 (June 2015): 96.

[6] North West Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, “Proposal to the John Heinz Neighborhood Development Program,” Proposal, 1995, Box 9, Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, Bronx County Histocial Society, (“NWBCCC Collection”). The Coalition was an umbrella organization that coordinated and implemented a broad-based organizing agenda that was established by its local member associations (See Julissa Reynoso, “Putting Out Fires Before They Start: Community Organizing and Collaborative Governance in the Bronx, U.S.A.,” Law and Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice. XXIC, no. 2 (Summer 2006) *32). In the early years of its activism, the Coalition focused on community revitalization, preventing the spread of arson throughout Northwest Bronx neighborhoods, and pursuing federal legislation that would require banks to lend money in the neighborhoods where they did business.

[7] Wolfe, 20.

[8] See John McQuiston, “At Rally in Bronx, Hundreds Clamor for Aid in Drug Fight,” New York Times, June 8, 1986.

[9] See “Drugs Out! 1500 Take to Fordham Road,” Action, Summer 1985.

[10] NWBCCC, “Do you want to see more foot patrols in your neighborhoods? Tired of Drugs,” Meeting Notice, September 11, 1984, Box 21, NWBCCC Collection.

[11] NWBCCC, “Follow-up planning meeting,” Meeting Agenda, NWBCCC Collection Box 21, September 26, 1984.

[12] NWBCCC, “Neighborhoods Win Foot Patrols!!,” Action 8, no. 1 (February 2, 1985): 1.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Community Patrol Foot List,” List with Map, NWBCCC Collection Box 21, circa March 1985.

[15] Clint Roswell and John Lewis, “Cop ‘failure’ on drugs protested,” New York Daily News, February 18, 1985.

[16] Roswell and Lewis, “Cop ‘failure’ on drugs protested.”

[17] NWBCCC, “NWBCCC Community Organizing/Community Development Meeting Report Sheet,” Report, February 28, 1985, Box 20, NWBCCC Collection.

[18] The phrase voir dire is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary as the “preliminary examination which the court and attorneys make of prospective jurors to determine their qualification and suitability to serve as jurors” (Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th ed. (St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1990). NWBCCC, “NWBCCC Community Organizing/Community Development Meeting Report Sheet.”

[19] This program was used in the Lower East Side neighborhood of Manhattan to target known drug corners and “sweep drug dealers and their customers from the streets” through increased police presence targeting known drug spots (Jane Gross, “In the Trenches of a War Against Drugs,” New York Times, January 8, 1986).

[20] Wolfe, 21 (quoting NWBCCC, Letter to Commander John McCabe about demonstrations & marches).

[21] Wolfe, 21.

[22] See “On the March Against Drugs,” New York Daily News, July 1, 1985.

[23] NWBCCC, “Summary of The Northwest Bronx Community & Clergy Coalition Drugs Out Organizing Effort,” NWBCCC Collection Box 20, circa 1986, 1.

[24] Ibid.