Days of Future Past: Dystopian Comics and the Privatized City

By Ryan Donovan Purcell

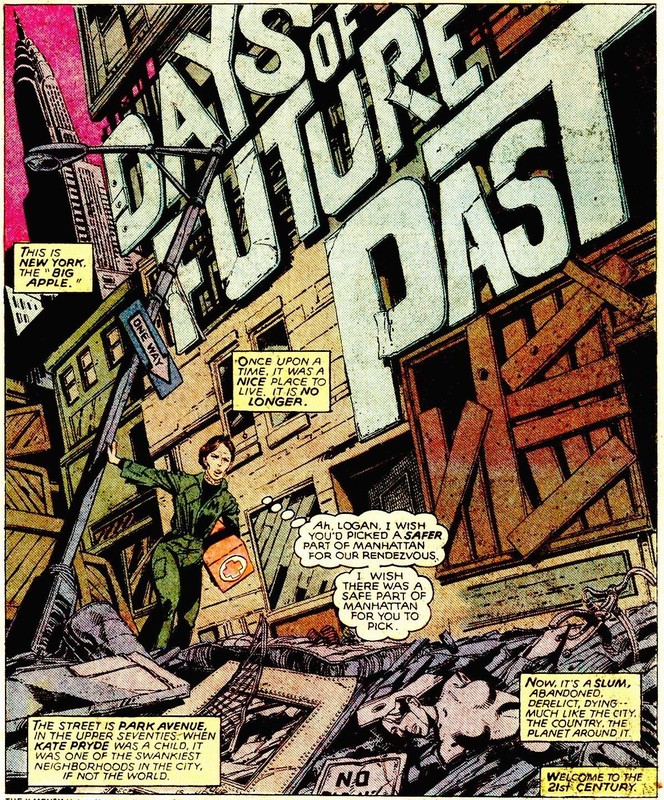

This title page of Days of Future Past (1981) bears a striking resemblance to and advertisement of the film Escape from New York released that same year.

“The past: a New and uncertain world, a world of endless possibilities and infinite outcomes. Countless choices define our fate — each choice, each moment, a ripple in the river of time — Enough ripples and you change the tide, for the future is never truly set.” This is the lesson Dr. Xavier learns at the end of the Marvel film, X-Men: Days of Future Past(2014). It’s a science-fiction alternative history in which the X-Men send Logan (Wolverine) back to the year 1973 to change their fate. In order to prevent the sequence of events that leads to mutant annihilation Logan must break into the Pentagon, prevent a landmark arms deal at the Paris Peace Accords, and save Richard Nixon from mutant radicals (as one might expect). The comic on which the film was based, however, is a far different story.

Published in January 1981, the comic is set in the ruins of New York City. It is a dystopian future in which a privatized police state has supplanted the US government. Congress has outlawed all mutants and super-humans. Those who have not been hunted down and murdered by the state are sent to the South Bronx Interment Camp where they perform forced labor and wait for their eventual execution. In response, the mutants and super-humans form an underground resistance and find a way to travel back in time to change history.

At first glance this comic may seem like a wild aberration from the X-Men’s mildly political flavor. But in the context of American politics of the 1970s and 80s, we can see it full of sharp statements directly responding to the historical moment in which it was created. It critiques the converging trajectories of the New Right, and the carceral state at this time. It draws connections between the privatization of the public sector, and the unprecedented expansion of the prison-industrial-complex. And in making these claims, the comic engages with the radical activist tradition of prison abolition when it equates mass incarceration with racial cleansing, and moreover, suggests such radicalism as the only viable resistance to the carceral state.

Days of Future Past offers us a vividly reflective text through which we can understand recent urban history. It reads as a radical critique of politics and society at the dawn of the Reagan Era. Through fiction, this dystopian narrative renders political history of the right (and of the left) more terrifying than we could ever imagine. In the end, however, this is a story about citizenship and New York City during the late-1970s.

I.

“This is New York, the ‘Big Apple,’” the comic begins. “Once upon a time, it was a nice place to live. It is no longer. The street is Park Avenue in the upper seventies. When Kate Pryde was a child, it was one of the swankiest neighborhoods in the city, if not the world. Now, it’s a slum, abandoned, derelict, dying — much like the city, the country, the planet around it. Welcome to the 21st century.”[1] The original 1981 comic version of Days of Future Past opened with a shattered cityscape set in the year 2013. Mutant Kate Pryde anxiously climbs over crumbling infrastructure of the Upper East Side. Broken street lamps, broken glass, a shredded chain-link fence, and sharp mattress springs, block her path. The splintered skull of a discarded mannequin mirrors the panic on the protagonist’s face as she makes her way uptown to the Bronx.

Distinctions between fiction and reality are sometimes blurred. In historical perspective New York City in this narrative looked something like the actual New York of the late-1970s and early-1980s, just as the city embarked on a similarly radical transformation. As infrastructure continued to decline among communities in the outlying boroughs, most acutely in the South Bronx, a new era of policing fundamentally altered New York’s crime policy. Increasingly aggressive police responses to misdemeanors, otherwise known as “quality-of-life offenses,” disproportionally impacted these same communities on the urban periphery. The resulting surge in arrest rates caused prison populations to rise through the 1980s and 1990s, contributing to what we now know as mass incarceration. During this time New York slowly developed some of the characteristics of the police state depicted in the comic.

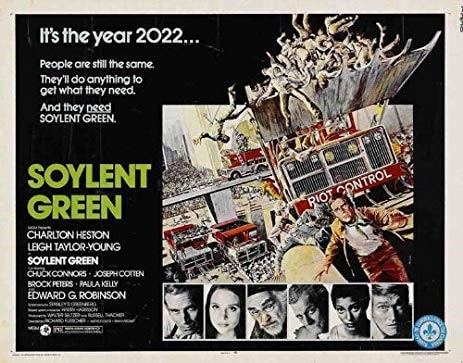

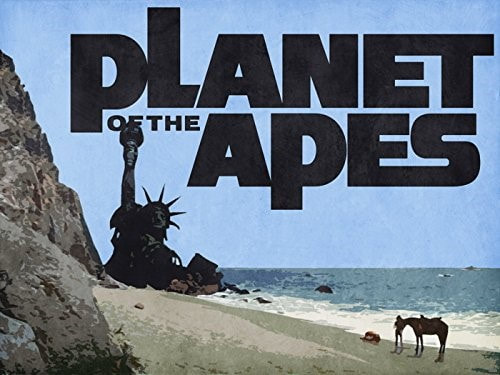

These movies, along with Days of Future Past (1981), are part of a shared moment in popular culture which features dystopias set in future New York City. Evident from their advertisements alone, these narratives employ similar imagery and tropes regarding urban apocalypse including mass incarceration, state privatization, privatization, and genocide.

II.

“I haven’t seen anything that looked like this since London after the World War II blitz.” That’s how Ronald Reagan then Republican Presidential nominee described the South Bronx in the summer of 1980. Reagan toured Charlotte Street in an effort to curry favor with Black and Latino voters months before his historic election. It was the same rubble-strewn lot President Jimmy Carter visited in 1977.

Photographers framed the candidate in front of a ruined brick building with bright orange graffiti that read, “Decay”; a building across nearby read “Broken Promises.” Down the street a busted, endlessly trickling hydrant bubbled away. Reagan addressed reporters with prepared statements about Carter’s failed plans to revitalize the South Bronx. He spoke squarely into the cameras, all but ignoring the dozens of local residents behind police barricades 25 feet away. The heat was intense.

“Yo, Reagan!” someone screamed from the restive crowd. “You ain’t gonna do nothing for the South Bronx!” The people shouted and demanded that Reagan speak to them directly. “Help us! Help us!” The governor could no longer ignore boos and jeers that bombarded him in front of cameras. Surrounded by a phalanx of reporters and police, he shuffled toward the crowd smiling nervously. “What are you going to do for us?” an elderly Latina woman asked Reagan repeatedly. He raised his hands, palms open to quiet the people, but they were too loud, too worked up. He finally raised his voice, and seemed to lose his temper. “Look if you listen—I can’t do a damn thing for you if I don’t get elected!” He continued to compete with the crowd, which grew more agitated by his lack of composure. “I am trying to tell you that there is no program or promise that a President or the government can make, to come in here and wave a magic wand,” Reagan shouted, his face running red. “It can’t be done!” At that moment Reagan’s security pulled him away into his limousine. “There we were, driving away,” Reagan later told reporters, “and you think of them back there in all the ugliness and they have no place to go. All that is before them is to sit and look at what we just saw.”[2]

Douglas E. Kneeland, “Reagan Urges Blacks to Look Past Labels and to Vote for Him,” New York Times, August 6, 1980.

The South Bronx has been a touchstone of Presidential politics from Carter to Clinton. It has been both a catalyst of power and source of political demise, in fact, at all levels of politics. Despite his humiliating attempt to politicize the South Bronx against Carter in 1980, Reagan’s presidential campaign was nonetheless victorious. The same could be said of Ed Koch’s use of the South Bronx in his 1981 gubernatorial campaign. Although unsuccessful, Koch ultimately was able to cultivate an image as an urban revitalizer that propelled his prosperous career as NYC mayor for three consecutive terms.

At the same time the South Bronx had long been a symbol of government negligence. Deteriorated infrastructure and corroded housing was a harsh reality for hundreds of families. This evidently accounted for the emotionally charged reception Reagan received in 1980. The South Bronx had been virtually abandoned by the government for decades. City services taken for granted elsewhere — such as police protection, garbage collection, and emergency services — could not be predicted with certainty, if they functioned at all in some sections of the South Bronx. A 1969 study conducted by the New York Times revealed that South Bronx residents had a 1 in 20 chance of dying a natural death. Most were dying in homicides or from drugs.[3]

New York City’s fiscal crisis in the mid-1970s compounded the damage inflicted on the South Bronx by deindustrialization, and the evaporation of a middle-class tax base due to suburbanization. And the city government had all but forgotten the South Bronx until its image and symbol became valuable political currency in the late-1970s. By the 1980s, with New York City leading the nation in rising incarceration rates, the South Bronx began to take on new meanings. While midtown-Manhattan became a testing ground for what came to be known as Broken Windows policing, the South Bronx began to exhibit many of its devastating consequences, namely aggressive policing tactics and mass incarceration. In popular culture Fort Apache, The Bronx (1981), set at the 41st Police Precinct, depicted the South Bronx as a criminal wasteland. Meanwhile the inmate population at Rikers Island, just south of Hunts Point, swelled. The Koch administration even proposed an 800-bed barge to accommodate the overflowing jail.[4] Much more than a political football, the South Bronx became symbolic of the emerging carceral state.

The symbolic uses of the South Bronx in political rhetoric, and popular culture have set it apart from the rest of the city. It has, as a result, become a dehumanized space in the American urban imaginary rendering its communities vulnerable to symptoms of the carceral state such as police acting as an occupying force, and the construction of prison barrages. At the root of this issue are problematic meanings associated with South Bronx’s symbolism.

Annual jail admissions in New York City, 1978-2014. Source: Vera Institute of Justice, 2015. Originally cited in Themis Chronopoulos, "The Making of the Orderly City: New York Since the 1980s." Journal of Urban History, May 2018.

III.

Comics have a strange way of reflecting these silent histories. Like other forms of popular culture, they can heighten our sensitivity to changes underfoot. And they can enable us to project our sympathies, and attitudes publicly, by drawing our attention, and spurring conversations about who we are in a given historical moment. Days of Future Past does this well.

As the comic’s title suggests, this dystopian vision of New York City has its roots in the recent past. In the comic, Congress passed a body of legislation in the 1980s that systematically stripped citizenship from mutant Americans, following the assassination of U.S. Senator Robert Kelly by radical mutants. The Mutant Control Act of 1988 specifically created a racialized hierarchy of citizenship in which there are three classes identified by letters that must be worn on clothing. “H” class is for “baseline human,” a person who the state has determined to be “clean of mutant genes,” and are “allowed to breed.” Secondly, “A” is for “anomalous human,” a “normal person possessing mutant genetic potential” and it therefore forbidden to breed. “M,” the lowest class, is for mutants, who are made “pariahs and outcasts” of society.

It is 2013 and Kate Pryde embraces her husband Rasputin (Colossus) in the South Bronx Mutant Interment Camp before traveling back to 1980 in the comic Days of Future Past (1981).

According to this plot, Congress also commissioned a private arms manufacturer to construct an army of robots, Sentinels, to enforce the anti-mutant laws. The Sentinels imprisoned mutants in internment camps across the country (the South Bronx was designated one such camp). Urban America adopted more aggressive policing tactics in which mutants were summarily “hunted down and — with a few exceptions — killed without mercy.” Quickly, however, the Sentinels took their mission too far, and overthrow the U.S. government, conquer the rest of North America, and set their sites on the rest of the world, threatening a nuclear holocaust. In response, the X-Men who have not been killed off or imprisoned form an underground resistance group. And using their mutant abilities they find a way to travel back in time to 1980 to stop the assassination of the Senator, which triggered the sequence of events that led to their confinement and genocide.

Not unlike this fiction, the late-1970s and early-1980s was a moment of the radical transformation in the American political landscape. As in the comic, to some this was a dystopian unfolding. The rise of the Right during the late-1970s hinged on the decline of cities, and New York City’s fiscal crisis exposed the deep faults of urban liberalism. As Kim Phillips-Fein claims in Fear City (2017) “the fiscal crisis involved discarding a set of social hope, a vision of what the city could be… It proved that using government to combat social ills would end in collapse. It proved a spectacular repudiation of the Great Society, the War on Poverty, even the New Deal.” Moreover, for ordinary people this moment “marked a change in what it meant to be a New Yorker and a citizen.”[5]

IV.

Days of Future Past vividly reflected this history and the implications of the South Bronx as symbol, countering its problematic meanings with a narrative of resistance and local agency. Its fictional description was reminiscent of the actual place, where prison and death were equally viable fates.

Kate Pryde arrives at the South Bronx Mutant Internment Camp. Immediately, she is subject to “an exhaustive — and intentionally humiliating” security screening to ensure that she is carrying no contraband. Pryde is then allowed to enter the camp, a place she and the remaining mutants must call home. The Mutant Control Act of 1988 gave the Sentinels an open-ended program, with fatally broad parameters, to eliminate the mutant presence from America. “By the turn of the century,” the comic explains, “virtually every mutant, superhero and super villain in the United States and Canada had been either slain or imprisoned.”

It is 2013 and Kate Pryde arrives at the South Bronx Mutant Interment Camp and is interrogated by robot guards in the comic Days of Future Past (1981).

Through this narrative authors Chris Claremont and David Byrne assert the place of comics in the canon of radical thought. Their story engages a rich body of literature critiquing the prison-industrial complex, echoing radicals from George Jackson to Angela Davis. Along these lines, the authors draw a direct correlation between mass incarceration and genocide, a framework in which police operate as instruments of state oppression. In the comic, however, Sentinel robots, produced and operated by Trask Industries (a private arms manufacturer), have superseded the role of the police and military. Their sole function is to hunt down mutants, a race that congressional legislation has set apart from the rest of society; Law and order becomes a means of policing this racial power dynamic, by imprisonment or murder if necessary. Through this lens, Days of Future Past emphasizes the role of the private sector not only in the militarization of police, and proliferation of prisons, but in what is tantamount to racial cleansing.

After traveling back from 2013 to 1980, Kate Pryde summarizes to the X-Men the political developments of the 1980s. The United States elects a xenophobic president, and passes laws restricting mutant citizenship in the comic Days of Future Past (1981).

We cannot lose sight of the fact that this is very much an American story, with New York City at the center. The two-part comic was published in January-February 1981, directly following President Ronald Reagan taking office. We might see this reflected in comic where in 1984 a “rabid anti-mutant candidate was elected president,” riding on a wave of “hysterical paranoid” (a possible reference to the surge of right wing populism during the 1970s). But in the narrative it’s 1980, when Senator Kelly is assassinated triggers the rise in mass incarceration — coincidentally, the same year Reagan was elected. “Once confident symbols of hope,” cultural historian Bradford Wright reminds us, many comic books by the 1980s, “now spoke to the paranoia and psychosis lurking behind the rosy veneer of Reagan’s America.”[6] Claremont and Byrne’s Days of Future Past is no exception as it repeatedly makes thinly veiled references to Reagan’s election and regressive social ideals. The plot jumps back and forth between 1980 and 2013 to establish a causal relationship between anti-mutant legislation and the carceral state that virtual eliminates all mutants. Ed Koch was elected mayor in New York City just two years prior to the publication of Claremont and Byrne’s comic. Koch ran on a platform to “clean up” the city, and once in office quickly called for a police crackdown on “quality-of-life offenses” with draconian penalties for minor transgressions. The historical immediacy of these politics and the publication of this comic is any thing but coincidental.

Comic books, cultural historian Bradford Wright reminds us, are history. “Emerging from the shifting interaction of politics, culture, audience tastes, and the economics of publishing, comic books have helped frame a world view and define a sense of self for the generations who have grown up with them.”[7] So how did comic books shape the minds of readers in the 1980s? Did readers pick up on those that subtly critiqued their world? Did they inform political outlooks? Was this true of Days of Future Past? This was not necessarily the case in regard to its critiques of policing in cities and mass incarceration. Prison populations continued to rise to unprecedented levels through the 1980s and 90s. Policing in New York City under the Giuliani and Bloomberg administrations became even more draconian and aggressive than under Koch. Reagan served two terms as President, and the American political landscape has only become more radically conservative.

So what takeaways can we pull from this dystopian narrative? For one, we can say that Days of Future Past is a shining example of what Wright means when he says that comics are history. As cultural texts, not unlike novels, newspapers, paintings, or poems, comics too are impressed with a host of dynamic historical forces that surround their creation. They are no less historically significant than any other document. Days of Future Pastdemonstrates the interplay between politics and popular culture, and the illuminating effects that result when they are brought into dialogue. Often the political context and cultural text reveal aspects of each other not easily rendered by themselves. The most pressing meaning we can take away from this story, however, comes through the mechanics of the narrative itself. In order to resist oppression the X-Men must travel back in time to change to history. They are, in a sense, performing a kind of historical work that exposes the roots of the power structure that dominates them. In this way, the authors suggest that history and writing as a way of resisting the carceral state.

The ending of the film version of Days of Future Past is perhaps truest to the sentiment expressed in the 1981 comic. Logan’s consciousness wakes into his future body after going back in time. He discovers that he is a history professor at Charles Xavier’s academy. “Don’t you have a history class to teach?” Xavier asks smiling at Logan who is deeply confused. “Actually I could use some help with that,” Logan responds. “Help with what?” the doctor asks. “Pretty much everything after 1973,” says Logan, “I think the history I know is a little different.”

Ryan Donovan Purcell is a PhD candidate in History at Cornell University, where he studies modern American popular culture and urban history. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, College Art Association, and Hyperallergic.

Notes

[1] Chris Claremont, John Byrne, et. al., The Uncanny X-Men: “Days of Future Past” (Marvel Comics, January-February, 1981).

[2] Douglas E. Kneeland, “Reagan Urges Blacks to Look Past Labels and to Vote for Him,” NYT, August 6, 1980; “Reagan, in South Bronx, Says Carter Broke Vow: Raises Voice Above Chants,” NYT, August 6, 1980; Steve Neal and Monroe Anderson, “Reagan Heckled in South Bronx,” Chicago TribuneAugust 6, 1980; “Reagan Booed in Bronx Slum,” Los Angeles Times, August 5, 1980; “Reagan courts blacks, urban areas; Argues with protesters in visit to South Bronx,” The Baltimore Sun, August 6, 1980. See also: Allen Jones, The Rat the Got Away: A Bronx Memoir (Empire State Editions, 2009); Evelyn Gonzalez, The Bronx (Columbia University Press, 2006).

[3] Richard Severo, “Bronx ad Symbol of America’s Woes,” NYT, October 6, 1977.

[4] The prison barge plan, was ultimately realized under Mayor Dinkins, and was called Vernon C. Bain Correction Center docked on the south end of Hunts Point; “Rikers Island timeline: Jail’s origins and Controversies,” March 18, 2017--http://www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/rikers-island-timeline-jail-origins-controversies-article-1.3001976.

[5] Kim Phillips-Fein, Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics (Metropolitan Books, 2017): pp.s 3-5.

[6] Wright, Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America (John Hopkins University Press, 2003): pp. 266.

[7] Wright, Comic Book Nation: pp. xv.