A New York Story: Kitty Genovese

By Marcia M. Gallo

Since 1964 the story of Kitty Genovese has shaped our expectations of community. It has served as a powerful cautionary tale, especially but not exclusively for women, at a time when new possibilities for independence and involvement drew many young people to big cities. Specifically, it was deployed to alert New Yorkers to a problem that did not exist: that of apathy. Activism was in the air and on the streets in 1964, and many New Yorkers joined local, national, and international organizing campaigns. Far from being apathetic, they gave their time and money as individuals to build groups and campaigns that could press their demands for reform and revolution. The infamous phrase “I didn’t want to get involved” was quoted in a front-page New York Times report in March 1964 that blamed the killing of Kitty Genovese on more than three dozen people—thirty-eight witnesses to a heinous crime. Her neighbors were castigated for a failure of personal and collective responsibility. Almost immediately, the story of a young woman’s death became a warning of the growing “sickness” of apathy. The media promoted an epidemic of indifference at the precise moment when millions of Americans were organizing for social change. The myth that resulted is at the heart of the paradoxical story of Kitty Genovese.

It is a myth that has inspired concrete social changes. In the decades since the shocking tale of uncaring neighbors first made headlines, it has become commonplace to call 911 in an emergency, but in 1964 that was not possible -- the 911 system did not exist. The Genovese crime hastened its development as one solution to the perceived problem of apathy. Like another hallmark of the crime -- psychological research into how and why people react when they see someone in trouble -- the emphasis was on understanding responses to crime. But in part the research that resulted in the theory of “bystander syndrome” was based on the assumption that the witnesses in Kew Gardens, because they lived near one another, behaved as a group rather than as individuals when they heard a young woman’s cries for help. Ultimately the studies exposed stark discrepancies between New Yorkers’ expectations of personal responsibility and community involvement.

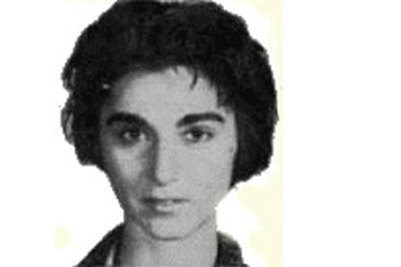

My own interest in Kitty Genovese began when I first saw her photograph. As a thirteen-year-old girl in Wilmington, Delaware, with dreams of living a grown-up life in New York City, I was riveted by the image of her pale heart-shaped face and piercing dark eyes. For me, she was a potent symbol of the horrible fate that could befall a woman bold enough to navigate the world on her own. Her story has haunted me ever since. As I finished high school, married, moved, divorced, moved again, came out, went back to school, and moved a few more times, Genovese’s story, as the poet Maureen Doallas has said, “stayed with me.” I could not shake her image from my mind nor forget the awful details that I remembered from newspaper accounts. Genovese was a reminder that, despite the changes brought about by 1960s social movements, freedom could have devastating consequences. From time to time over the years I caught references to her name and read articles about the bystanders who did not help her, but without learning much more about the woman she had been. That changed in 2004. In February, to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of Genovese’s death, a powerful feature in the New York Times brought her to life for me. The cipher became a person, one who laughed and danced and was devoted to her family and friends, who included a female lover. As I sat at the computer at home in Brooklyn writing my dissertation on the first American lesbian rights organization, friends from all over the country brought the lengthy story in the Sunday Times to my attention. At that point I knew I had to learn more about Kitty Genovese.

The most popular image of Genovese - a mug shot taken in 1961 for an arrest on minor gambling charges. The New York Times used the image frequently, without ever mentioning the arrest.

The more I learned, however, the more apparent it became that newspaper and other media accounts eliminated salient facts from the narrative. Also missing was any sense of the vivacious twenty-eight-year-old Italian American woman who drove a red Fiat around New York in the early 1960s. I realized that she had been flattened out, whitewashed, re-created as an ideal victim in service to the construction of a powerful parable of apathy. It seemed to me that Kitty Genovese’s personhood had been taken from her, first by her murderer and then by the media, in order to serve a greater good. The erasure of the facts of her life ensured that she would not be the focus of the story. Instead, her twenty-eight years of existence were reduced to one sentence in most early news accounts, while the awful details of her death were transformed into an international saga of her neighbors’ irresponsible behavior.

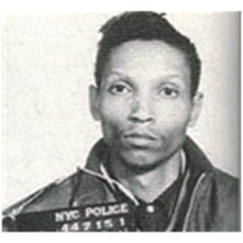

In the construction of the story of Kitty Genovese, neither Genovese the victim, nor the perpetrator, a twenty-nine-year-old African American man named Winston Moseley, nor the senselessness of the violent crime itself was ever at the heart of the matter. In the Times’ telling of the tale, both Genovese and Moseley were overshadowed by the people who lived across the street from Kitty in Kew Gardens, a quiet neighborhood in Queens where such horrible things were not supposed to happen. The very scene of the crime was aberrant. It was not a place that was associated with violence. For many New Yorkers in 1964, the opposite was true: Kew Gardens was considered safe because it was largely middle class, almost all white, with well-maintained single-family homes and midrise apartment buildings on narrow tree-lined streets. Many residents of Kew Gardens knew their neighbors, spoke to them on the street when they passed, did their shopping and socializing in the stores and restaurants along Lefferts Boulevard and Austin Street, much as Genovese and her girlfriend Mary Ann Zielonko had done. But two weeks after the crime took place, the New York Times highlighted a story, initiated by local police complaints, that blamed her death on her neighbors. The women and men of Kew Gardens took center stage in the media drama that then unfolded, making them infamous as bystanders.

The story of Kitty Genovese as constructed by the Times generated social and political questions in a city divided along lines of race and class. New Yorkers in 1964 were increasingly feeling the impact of rapid social change, which was often equated with race, the deterioration of communities, and upheavals in gender and sexual norms, all of which spiked in the last decades of the twentieth century. Historian Elaine Tyler May summarized the era: “The civil rights movement challenged racial hierarchies, and women were challenging domesticity by entering careers and public life. The counterculture, the antiwar movement, and the sexual revolution added to the sense that the tight-knit fabric of the Cold War social order was coming apart.” The story of urban apathy was promoted at a time when the intensifying war against crime dominated political discourse and undercut debates about racial justice. The racialization of crime, based on the increasing identification of wrongdoing with people of color, solidified a process that had been under way throughout the twentieth century and fundamentally affected America’s cities. “The idea of black criminality was crucial to the making of modern urban America,” asserted historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad. “In nearly every sphere of life it impacted how people defined fundamental differences between native whites, immigrants, and blacks.” It can be seen in media accounts as well as popular culture, and the story of the Genovese crime and the political responses to it fit within this context.

Furthermore, some people began to look inward and examine their consciences on hearing about the Kew Gardens neighbors. They asked themselves and one another: Who had we become if we could stand by silently and ignore someone’s cries for help? The answer took many forms: condemnations of urban density and disconnectedness, the atomizing effect of popular culture, the growth of individualistic survival strategies in a dog-eat-dog world, and the disintegration of community. Tensions that had escalated during two years of protests over the intransigence of racial segregation in New York City education, housing, and employment, as well as ongoing instances of police violence against blacks and Latinos, exploded in the summer of 1964 at the same time that Moseley was being tried and sentenced. Genovese’s rape and murder took place near the start of a meteoric rise in the crime rate in New York City, which led to growing fears of victimization among residents and calls for shifts in policing strategies throughout the city. Changes in other public policies soon followed. The political reactions to her death, informed by local as well as national discourses on race and crime, gender and sexuality, involved law enforcement, social scientists, activists, and community organizations.

“For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.” With this sentence, on March 27, 1964, the New York Times introduced its account of one of the city’s most notorious murders. While the headline of the front-page article caught readers’ attention -— “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police” -- it was its subhead that established the moral of the story: “Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector.” When the report first appeared, it was as if a bomb had been detonated in the middle of Manhattan. “Kitty Genovese” and “Kew Gardens” dominated conversations and captured the attention of the city, highlighting fears at a time of growing mistrust among residents and a sickening sense of the city in decline.

The story began when the life of Catherine S. Genovese ended early on Friday, March 13, 1964. She had done nothing out of the ordinary, nothing more than what she often did: drive home from work. According to bartender Victor Horan, who was the last person to speak to her before she died, Genovese said good night to him about 3:10 a.m. and headed home to her Kew Gardens apartment from Ev’s Eleventh Hour, the tavern where they worked. Genovese was the manager of the small neighborhood bar in Hollis, Queens. Usually the drive from Hollis to Kew Gardens took her about fifteen or twenty minutes, depending on the time of day.

On this cold morning, as she made her way through the quiet streets, Winston Moseley spotted Genovese driving in her red Fiat and followed her. He saw her pull into the Long Island Rail Road station parking lot on Austin Street, the narrow tree-lined semi-commercial street where she lived in a second-story apartment, and park her car. He then stopped his car and left it parked at a bus stop next to the lot. Moseley later told police that Genovese saw him watching her as she got out and locked her car door. She ran from him, heading up Austin Street toward Lefferts Boulevard. Moseley caught up with her and stabbed her twice in the back. She began screaming for help, which alerted at least one neighbor in the Mowbray Apartments, the midrise building directly across the street. The neighbor lifted his window and shouted at Moseley, “Hey! Get out of here!” Moseley said that he saw other apartment lights switch on and he ran back to his car.

Realizing that his white Corvair was visible under the streetlight, and fearful that someone in the neighborhood might be able to read his license plate, he got in, started the ignition, and backed his car into nearby 82nd Road. Then Moseley sat in his car and waited. After ten minutes, seeing no one approach, he changed from a knit hat to a fedora in order to disguise himself and returned to Austin Street to search for Genovese. She had picked herself up from the sidewalk and made her way toward her apartment building, which faced the walkway near the railroad tracks on the far side of the parking lot. She was bleeding from the stab wounds Moseley had inflicted but was able to open the door of the first apartment a few doors down from hers. She collapsed inside on the floor of its small entryway. At the same time, Moseley had looked for her inside the railroad station building, which was empty, and then went up the walkway next to the tracks, trying the doors of the apartments. He found Genovese inside the foyer at 82–62 Austin Street. When she saw him she cried out again. He stabbed her in the throat to keep her quiet and then continued stabbing her in the chest and stomach repeatedly. He told police that he thought he heard and glimpsed someone at the top of the stairs opening the door, but when he looked up, he saw no one there.

Moseley’s description of his two attacks on Genovese included details of a sexual assault while she lay dying. He cut open her blouse and skirt, as well as her girdle and panties, removed her sanitary napkin, and attempted to rape her. Unable to penetrate her, he went through her pockets and then ran off with some of the personal items he found, leaving her bleeding profusely and now unable to speak or cry out. Within minutes after Moseley left, Genovese’s neighbor Sophie Farrar rushed to help her. She had received a telephone call from another neighbor telling her that Kitty had been attacked. Farrar rearranged Genovese’s ripped clothing and held her in her arms while they waited for the police and the ambulance, both of which arrived within minutes. It was now about 4:00 a.m. Genovese died on the way to Queens Hospital.

Police officers then awakened Mary Ann Zielonko, who shared the apartment at 82–70 Austin Street with Genovese. They brought her to the hospital to identify Genovese’s body. They also began knocking on the doors of the people who lived nearby, trying to piece together the details of what had happened. They interviewed the local milkman, Edward Fiesler, who provided information about the man he had seen walking on Austin Street that morning during his deliveries. Less successful were the police questionings of more than forty people throughout the rest of the day. The officers heard repeatedly from many of the neighbors that they had been awakened by screams but “saw nothing.” Some neighbors refused to answer any questions; one couple admitted that they thought they had glimpsed or heard a “lovers’ quarrel” and decided it was none of their business.

Genovese’s death quickly made the news. Local papers such as the Long Island Press put it on the front page the same day it happened, as did Newsday. The Press highlighted the story, running it on the front page under the headline “Woman, 28, Knifed to Death.” They also helped publicize police requests for information from anyone who might have seen the murderer. The New York Daily News printed the details on page one the next morning; the New York Times treated the story as a relatively unimportant crime report and gave it four short paragraphs on page twenty-six on March 14. Five days later Moseley was captured in another part of Queens as a result of the quick action of suspicious homeowners who spotted him burglarizing a neighbor’s house. The two men disabled his car to keep him from fleeing the scene and called police, who caught up with Moseley as he walked away from the Corona neighborhood. Realizing that he matched the description of the man wanted in the Kew Gardens case, Queens police questioned Moseley about Genovese. He readily confessed not only to her murder but also to two other deadly attacks on women in the previous year. He then told police about numerous sexual assaults and hundreds of burglaries.

It was because of his confession to one of the other murders that Moseley originally came to the attention of Times metropolitan editor A. M. Rosenthal, a Pulitzer Prize–winning foreign correspondent recently returned to New York to assume the editorship of the city desk in an effort to freshen the paper’s appeal to New Yorkers and halt declining sales. In the midst of orienting himself again to the city of his youth, and alert to its many changes during the decade he had spent reporting from other countries, Rosenthal was struck by a growing sense of fear and alienation among New Yorkers that coincided with a rise in crime. The attention given the Kew Gardens killing by other papers awakened him to the realization that the Queens story might be bigger and more significant than just another homicide in an outer borough. After talking about it with the city’s police commissioner, he decided to investigate. The result was the March 27 front-page story, written by Martin Gansberg, which blamed Genovese’s death on the indifference of her neighbors. It quickly dominated all subsequent coverage and became the official version, especially when Rosenthal published a book about the case, titled Thirty-Eight Witnesses, less than three months later.

In all of the accounts that have followed in the story’s wake, what has rarely been noted is that there is only one actual eyewitness to Genovese’s death. That person is her killer, Winston Moseley. It was his confession to Queens police that provided the singular account of the case. His crime brought him notoriety and a life spent in prison; it also placed him, and Kitty Genovese, in a triangulated relationship with one of the most powerful men in New York City and arguably the world, A. M. Rosenthal, who would go on to become executive editor of the Times. It was Rosenthal who made “the manner of her dying” into a morality tale despite the complex circumstances surrounding it.

The Times story hit a nerve with New Yorkers. Neither the initial factual and interpretive errors, nor the sense among more seasoned crime reporters at the time that the story of apathetic neighbors did not “sit well,” undermined the paper’s version of the events in Kew Gardens. This likely was due to the fact that the New York Times, known as the “Gray Lady” for its stolid eminence, was internationally renowned for factual coverage and unbiased reporting. The Times’ long-standing status as “the paper of record” provided it with immunity from overt criticism. As one journalist wrote: “When Rosenthal joined the New York Times as a city reporter in 1944, that newspaper and others wrote the ‘official record’ in relatively objective fashion. At his retirement [in 1986], investigative reporting had blossomed, with newspapers going far beyond the official record; papers regularly devoted dozens of columns to stories probing the mores and morals as well as the misfeasances of society.” The advent of television meant that newspapers were no longer the main source of news for most people, necessitating a shift toward interpretation beyond “the twenty-two minutes available on a network evening news broadcast.”

Just as significantly, media approaches to crime reporting were changing at this time. The media analyst Chris Greer points out that contemporary media highlight “the criminal victimization of strangers.” Furthermore, Greer notes, “The foregrounding of crime victims in the media is one of the most significant qualitative changes in media representations of crime and control since the Second World War.” Since the early 1960s, and in the decades since Genovese’s death, “victims have taken on an unprecedented significance in the media and criminal justice discourses, in the development of crime policy, and in the popular imagination.”

The New York Times’ coverage of the Genovese murder is a prime example of this shift. The media, across formats, tend to focus on the most egregious examples of crime and victimization, emphasizing images of violent and, frequently, sexual offenses. This is true despite the fact that property and drug crimes are the most common offenses. Yet these are given less attention, if not ignored altogether. The media’s focus on violent crime is highly selective as well: not all crime victims receive equal attention. Media resources are most often allocated to those victims who can be portrayed as “ideal.” The “Ideal Victim” is the person or category of people who are socially normative and “vulnerable, defenseless, innocent, and worthy of sympathy and compassion.” The erasure of the non-normative details of Kitty Genovese’s life enabled the media to present her as an Ideal Victim in telling the story of her death.

The dramatic tensions inherent in city living, as represented by the story of unresponsive neighbors and the creation of the myth of urban apathy, have been transmitted vividly through popular culture. In addition to the multitude of newspaper accounts, feature stories, popular books and films, and scholarly articles, there are numerous fictionalized accounts of the Genovese crime, all of which share one basic trait: the tragic propensity of “good people” to remain passive in the face of evil. The story began its artistic circulation within weeks of the news of her death. “Kitty Genovese’s screams were ignored in 1964, but she has been embraced as a pop culture icon ever since,” wrote one scholar. “Musicians, playwrights, and filmmakers have all found meaning in the story of her murder and its 38 witnesses.”

The story also led both real-life and fictional heroes to act boldly in the face of danger, starting with Genovese’s younger brother William, known as Bill, who volunteered for the U.S. Marine Corps two years after her death and lost his legs during a dangerous mission in Vietnam. It inspired many people, such as Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor of the United States Supreme Court, who reported in her memoir that she won her first extemporaneous speech competition at her Bronx high school in the mid-1970s by selecting the Kitty Genovese story from among the topics available for student presentations. The US Airways pilot Captain Chesley Sullenberger mentioned the story as an important personal influence in interviews given after he safely landed a distressed commercial jetliner in the Hudson River off lower Manhattan in January 2009. But the emphasis on apathy also provided a dark rationale for vigilantism. For example, it was portrayed as the inspiration for the creation of Rorschach, the violent protagonist of the dystopian 1986 comic book Watchmen, as well as a reallife vigilante, Kew Gardens native Bernhard Goetz.

Through the sensationalism of the story, Genovese’s anonymous neighbors became larger than life. As she was stripped of substance, they were transformed into sobering symbols of the anomie of city life. The account of the death of Kitty Genovese that the Times created resulted in the demonization of a New York neighborhood and the suppression of the truths of one young woman’s life. The emphasis on the neighbors’ noninvolvement, however, debuted during a time of increasing community mobilizations. The architect of the Genovese story, A. M. Rosenthal, used the crime as a clarion call for personal involvement and discounted what he termed “impersonal social action.” The exclusive focus on apathy as the moral of the story disparaged those New Yorkers who challenged the status quo, from race relations to police accountability to gender and sexual norms. Examining the story of Kitty Genovese from the vantage point of today provides an opportunity not only to look beyond the headlines of past decades but also to evaluate its legacy...

Marcia M. Gallo is Associate Professor of History at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. This is an excerpt from her new book, "No One Helped": Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy, published courtesy of Cornell University Press. The book has won the prestigious 2015 Publishing Triangle Judy Grahn Award for Lesbian Nonfiction and the 2015 Lambda Literary Awards for LGBT Nonfiction, and was a finalist for the 2015 USA Best Book Awards.