Rapid Transit in the Steam Age: Brooklyn Steam Wars

The Dawn of Rapid Transit in NYC: The LIRR in the Steam Age

by Elizabeth K. Moore

Brooklyn

Steam WArs

Traffic at Atlantic Avenue and Fifth Avenue, Brooklyn, circa 1895. New-York Historical Society.

The old tunnel, that used to lie there under ground, a passage of Acheron-like solemnity and darkness, now all closed and filled up, and soon to be utterly forgotten, with all its reminiscences; however, there will, for a few years yet be many dear ones, to not a few Brooklynites, New Yorkers, and promiscuous crowds besides.

For it was here you started to go down the island, in summer.

- Walt Whitman, 1862

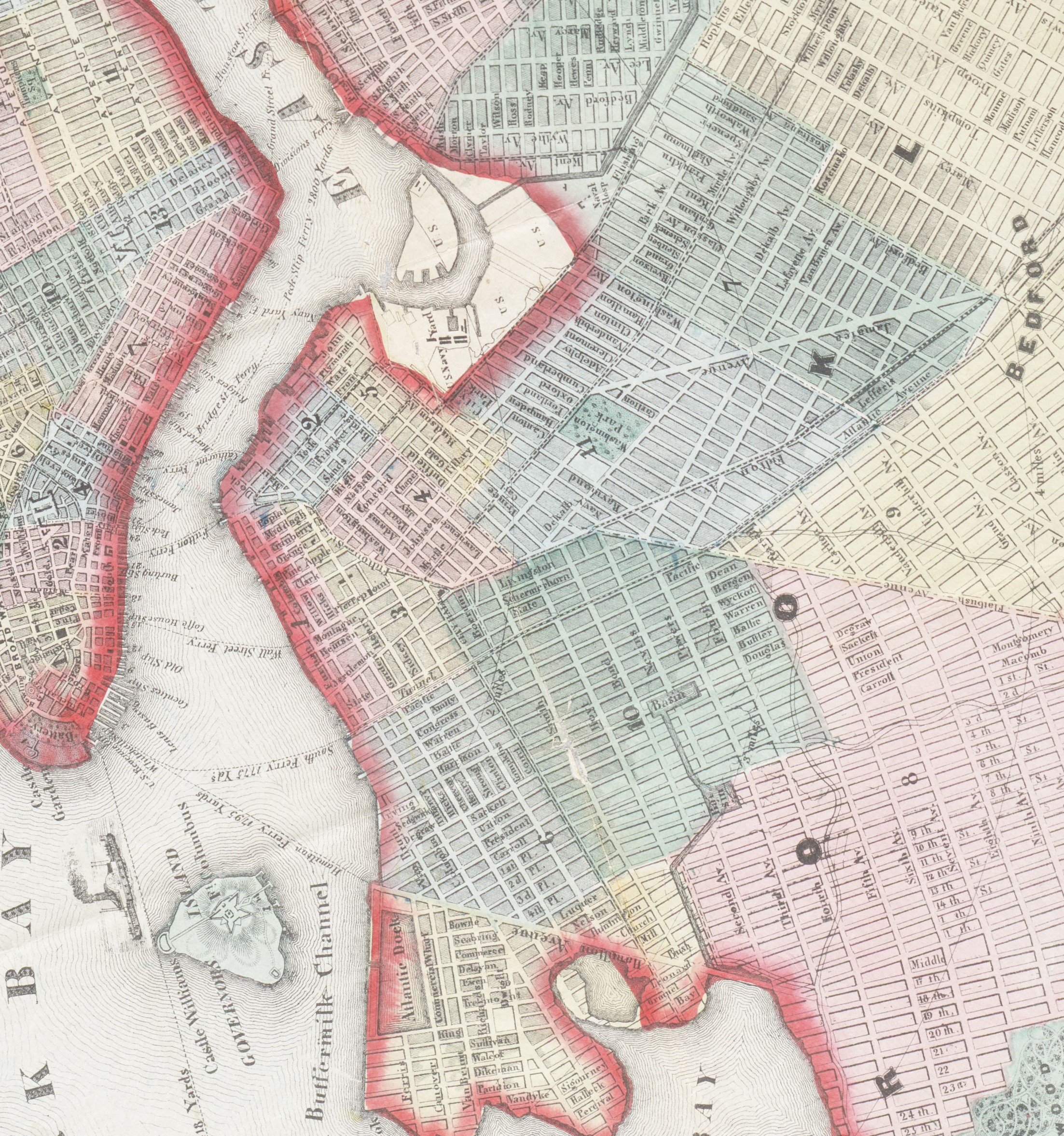

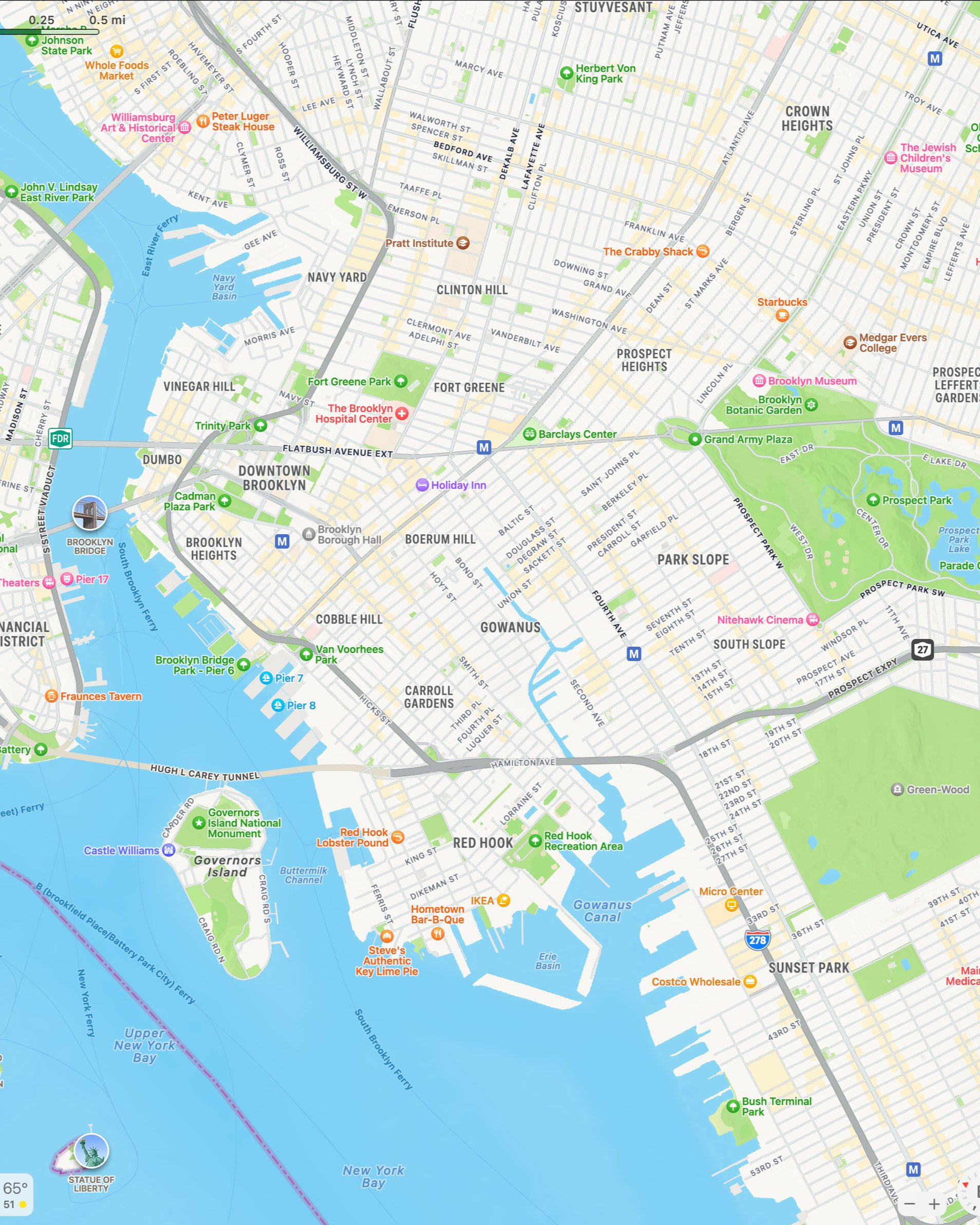

Whitman was half right. A controversial tunnel built by the Long Island Railroad to link the Brooklyn waterfront with Greenport, but closed after fifteen years, was utterly forgotten by Brooklynites, regarded as an urban myth for more than a century. But it had not been filled up. And in 1980, a curious New York engineering student named Robert Diamond would drop through a manhole cover on Atlantic Avenue and revive the buried history of what he called the world’s first subway.

The Atlantic Avenue tunnel, just steps from the New York City Transit Museum, is now a familiar piece of Brooklyn lore. But less attention has been paid to the story of its importance, or to the fractious, decades-long debates about whether this railroad was building up the rapidly growing city, or endangering it.

The LIRR brought the first jolt of suburban modernity to the sleepy farming village of Bedford, and its return from a long banishment later in the century would nourish the birth of Bedford’s celebrated landmark district, as well as communities and industries further east on Atlantic Avenue. But local and regional interests did not always align.

The railroad’s financing was coming largely from New York and Boston interests seeking a speedy coastal connecting route for passengers, light merchandise and the U.S. Mail. The village of Brooklyn had put itself on record as a strong supporter, in part to assure that rapidly growing Williamsburgh did not become the leading city of what some called a future “State of Long Island.” East End farmers wanted an economical way to deliver produce to New York. Others foresaw an international port for steam packets and passenger vessels at Greenport. For all this, rail facilities at the South Ferry were an imperative.

Museum of the City of New York

A sketch of the tunnel in Henry Isham Hazelton’s 1924 history, The boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, counties of Nassau and Suffolk, Long Island, New York, 1609-1924

Both the steep slope to the waterfront and the hostility of local residents compelled the tunnel project, its cost variously priced at $66,000 to $100,000. The LIRR excavated a 2,000 foot, open-cut tunnel, lined with brick and extending from Boerum Place to Columbia Street, the site of today’s Brooklyn Bridge Park. Above the tunnel it paved Atlantic Street for city traffic. Locomotives were allowed to travel between Bedford and South Ferry at speeds no greater than 6 miles per hour — following a man on horseback waving a red warning flag. Train whistles were forbidden in the city; for a while, the locomotives were even disguised under boxes, to avoid frightening horses. The tunnel opened in December 1844.

Writing for the Brooklyn Standard in 1862, Walt Whitman would recall that daily eastern train, filled with summer passengers, starting for Greenport:

The bell rings, and… off we go. Every person attached to the road jumps on… The orange women, the newsboys, and the limping young man with long-lived cakes, look in at the windows with an expression that says very plainly, “We’ll run along-side, and risk all the danger, while you find the change.” The smoke with a greasy smell comes drifting along, and you whisk into the tunnel.

The tunnel: dark as the grave, cold, damp, and silent. How beautiful look Earth and Heaven again, as we emerge from the gloom! ...

“Even rattling along after the steam engine, people get a consciousness of the unrivalled beauties of Brooklyn’s situation… the hills of Greenwood, and the swelling slopes that rise up from the shore, Gowanusward… the little cove that makes in by Freek’s mill… and the green knolls and the sedgy places…”

The crushing expense of the tunnel doomed the railroad’s Boston express service within three years of its opening. In 1847 a demand for payment from tunnel contractor William Beard prompted the seizure of the railroad’s last ferry, forcing it abruptly to cancel the service. Locomotives would continue drawing passengers and freight from South Ferry through the tunnel for another dozen years, though, driving development and transformative change down Atlantic Avenue.

Brooklyn’s safety measures meant that the ride from the ferry to Jamaica took a tedious 55 minutes. But even this compromise was unsatisfactory to some of its neighbors. It wasn’t just the locomotives, with their noise, cinders, the way they alarmed horses or the gruesome accidents they caused. The LIRR’s primary revenue stream came from fertilizer for farmers, which meant a ceaseless parade of rail cars down Atlantic Avenue loaded with street muck, bones, ashes, the scrapings of stables and pigpens, and the euphemistically named “poudrette” — dehydrated privy waste from unsewered homes.

In 1850, Brooklyn’s Common Council passed an ordinance banning steam from Atlantic Street. The railroad got a court injunction blocking that ban, but it only revived the battle, which would wind its way through the courts, the mayor’s office and finally Albany.

The LIRR protested that it had spent as much as $100,000 to build the tunnel, Atlantic Street and the South Ferry improvements to resolve landowners’ complaints.

“We would ask if there is any man who believes that part of the city (of Brooklyn) would be in the present advanced state, had it not been for the Long Island Railroad?” the New York Daily Times asked. “Our answer is NO.”

Across the river, the New York and Harlem Railroad was barred from using steam south of 42nd street in 1854. But unlike the Harlem, such a ban would cut this railroad off entirely from Brooklyn’s waterfront. Four hundred landowners and businessmen signed a petition siding with the railroad, and in 1853, “for the purpose of terminating this long and harassing question,” the state legislature ratified a deal whereby the railroad would shift its tracks to the center of a newly widened and level Atlantic Avenue, and the city gave up its authority over the railroad, whose right to use steam was now, according to the legislation, “secured.”

Nevertheless, five years later, after an aggressive pressure campaign reportedly stage-managed by land speculators, the state expelled the Long Island’s steam locomotives from the city of Brooklyn.

1857 broadside against steam trains on Atlantic Avenue. Courtesy New-York Historical Society.

LIRR train at Howard House, East New York, Brooklyn, April, 1865. The hotel is draped with bunting in mourning for President Abraham Lincoln. Queens Borough Public Library, Ron Ziel Collection

Steam locomotives westbound from Jamaica would only be permitted to travel as far as East New York before their passengers would have to get out and change to horse cars. Electus Litchfield, Brooklyn’s wealthy speculator in railroads and real estate, now bought the Brooklyn and Jamaica tracks that had carried LIRR trains through the city. He established a depot at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, and bought 230 horses to replace the steam engines.

The railroad found a new East River terminal site for its Manhattan-bound commuters in Hunter’s Point.

The wide-open wetlands of their new East River home were quickly converted from greensward to railyard with the deposit of vast amounts of fill. That allowed the LIRR to erect a spacious depot, new engine houses and machine shops. Commuters and businesses adapted fast. As the authors of Gotham note, “King’s loss proved Queens’ gain. Soon Hunters Point resembled a western boomtown… (with) hotels, saloons, boarding houses, kerosene refineries, coal and lumber yard.” Housing, churches and schools followed; Long Island City was incorporated in 1869, and became the Queens county seat three years later. The railroad established a fresh produce market on Borden Avenue in 1875.

Long Island City 1884 as depicted by the railroad. From Long Island of Today, courtesy of the New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections Division.

In Brooklyn, meanwhile, activity in the once-lively business district at the foot of Atlantic Avenue had died out almost immediately. Hotels closed. Banks and insurance companies moved away. The South Ferry canceled six boats. The once-large riverside produce market withered.

Tenement houses, saloons and second-hand stores moved in below Flatbush Avenue; the waterfront became a notorious crime district. Authorities repeatedly broke open the old tunnel to disprove rumors that it had become a pirates’ lair or a thieves’ redoubt.

Atlantic Avenue, Drive and Promenade, by Henry Seibert. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

As new rail lines proliferated just about everywhere else in the country, Brooklyn’s business community pushed to reopen the “steam question.” Finally, the city and state agreed to allow a rapid transit service pulled by lightweight “dummy” locomotives, but only as far as the intersection of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues. Litchfield’s stable would become the new train depot. The tunnel would remain sealed.

Detail of a depiction of Atlantic Avenue in front of Florian Grosjean's Queens mansion after steam locomotives returned to Brooklyn in 1877, projectwoodhaven.com

LIRR tracks passing the Lalance-Grosjean factory, circa 1900, projectwoodhaven.com

The new local rapid transit reopened in June 1877 and was an instant success, running 41 trains each way daily.

That same month, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle announced the planned sale of the “North Farm,” a large piece of land a couple of blocks from the tracks that had belonged to onetime LIRR director Leffert Lefferts Jr. That kicked off the rapid development, of the Bedford Historic District, a celebrated collection of row houses that has become the architectural jewel of residential Brooklyn.

In Woodhaven, Queens, the railroad served a flourishing community growing up around the enamel cookware factory, Agate Iron Ware, that had been established by French industrialists Charles Lalance and Florian Grosjean in 1863 and employed 2,100 workers.

How much was Brooklyn’s residential growth boosted by the railroad’s return? To be sure, horsecars already were abundant, and the Brooklyn Bridge was under construction. Still, explosive growth had followed Manhattan’s introduction elevated railways — on avenues safely distant from the trains’ smoke and noise. The LIRR’s rapid-transit “dummies,” running inside wrought-iron fences, had convenient stops every few blocks at stations named for the avenues they crossed: Vanderbilt, Grand, Nostrand, Brooklyn and Kingston; Troy, Utica, Ralph, Saratoga and Rockaway.

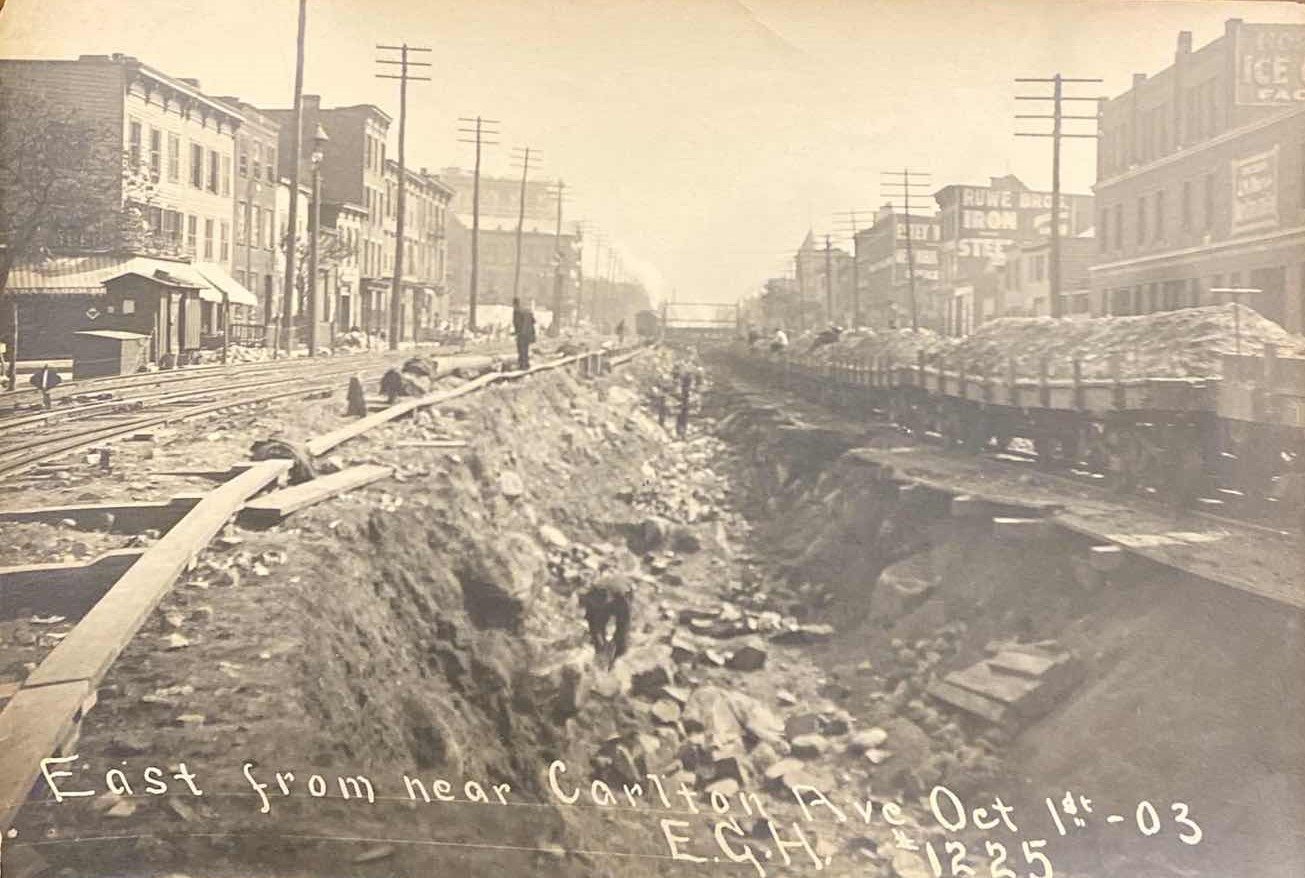

At every crossing, safety gates were lowered, and traffic stopped. Inevitably, as other streetcar and elevated train lines multiplied with Brooklyn’s population, the complaints again mounted. These slow, dirty steam trains were dividing and delaying a busy, growing city that was now the fourth largest in the country.

Atlantic Avenue, East New York, circa 1890. William J. Rugen Image Collection, Queens Borough Public Library.

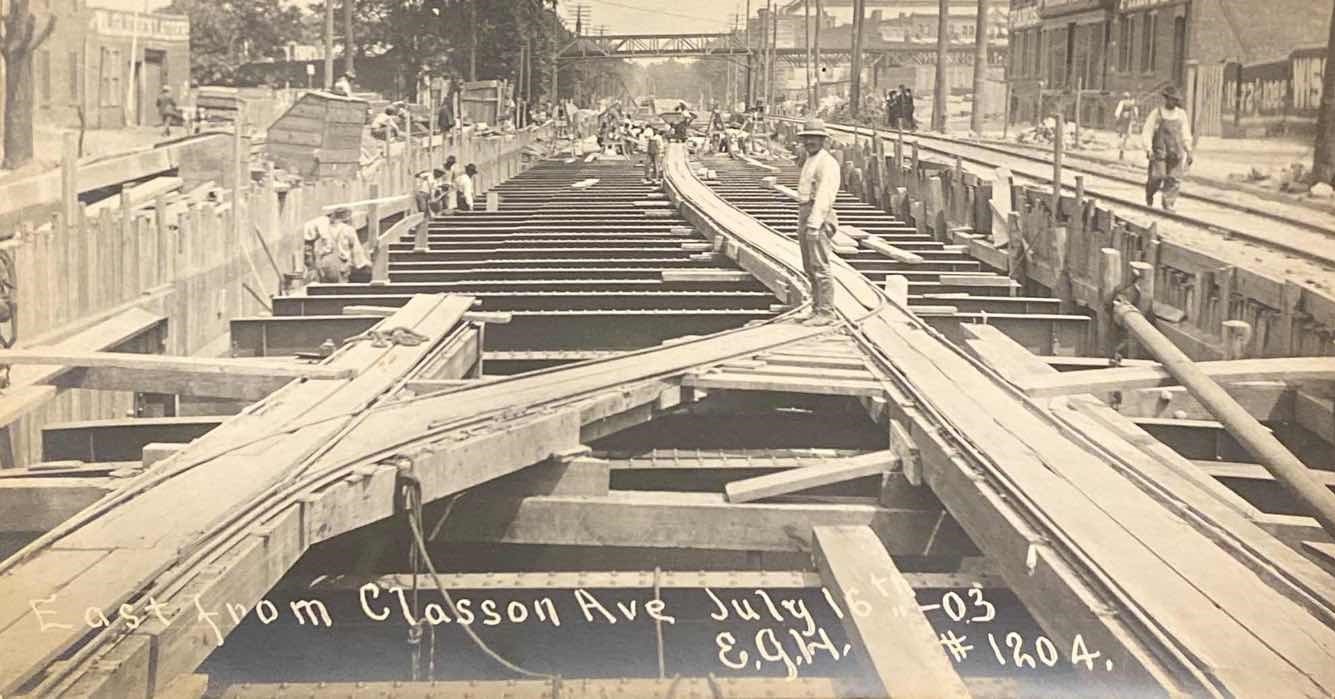

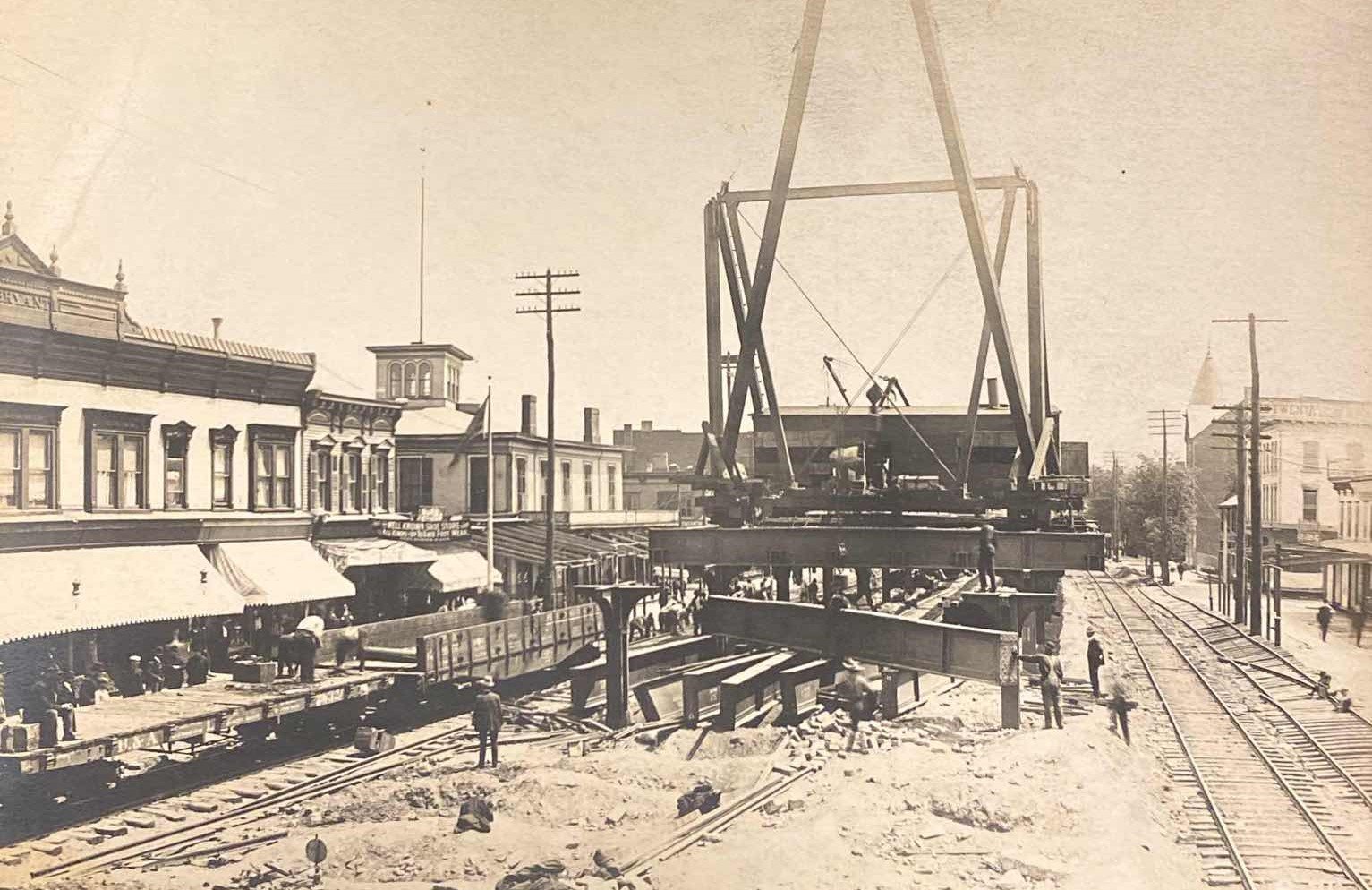

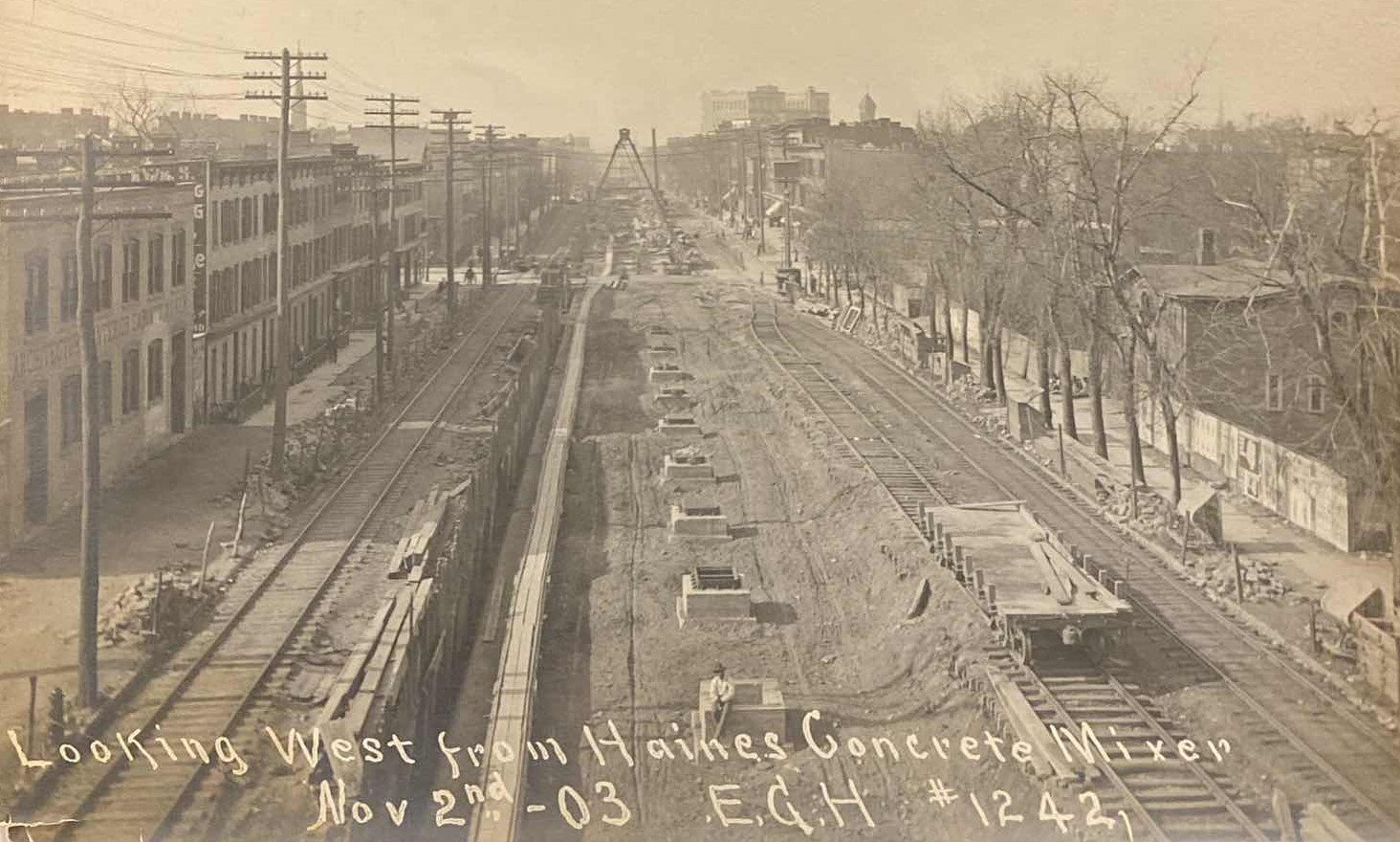

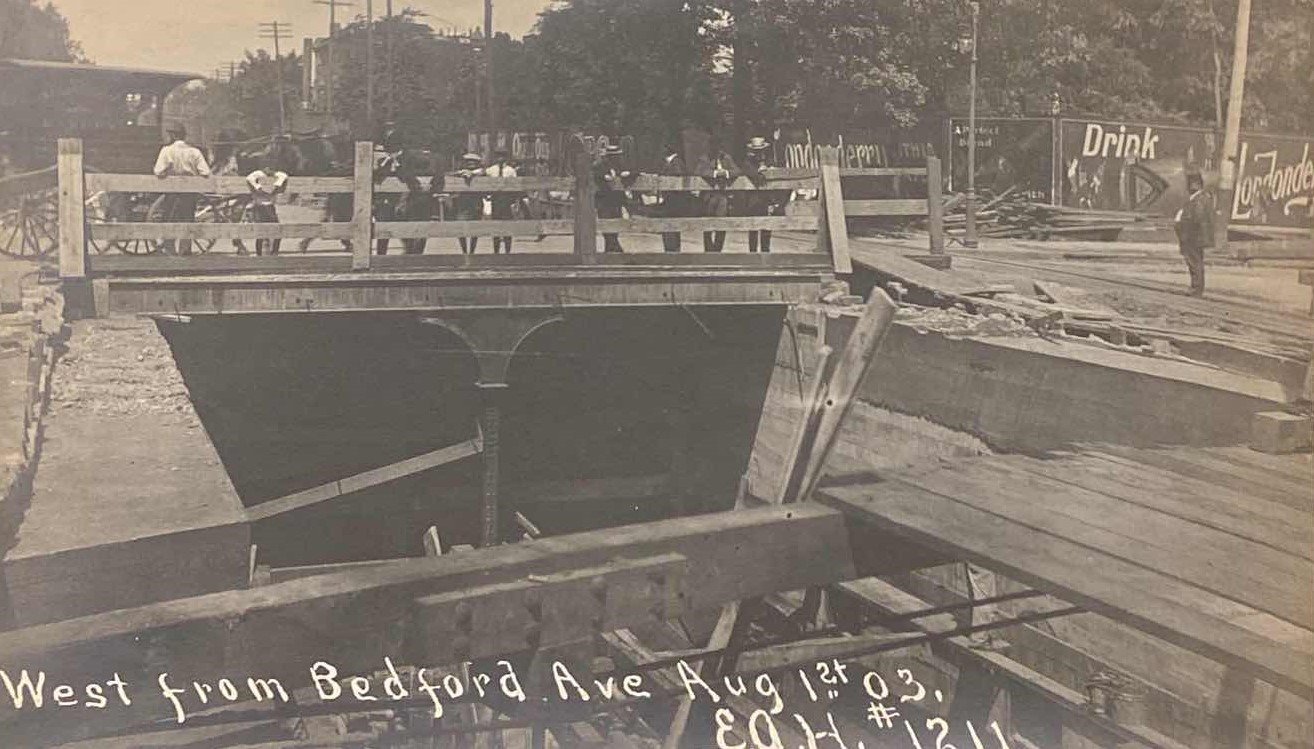

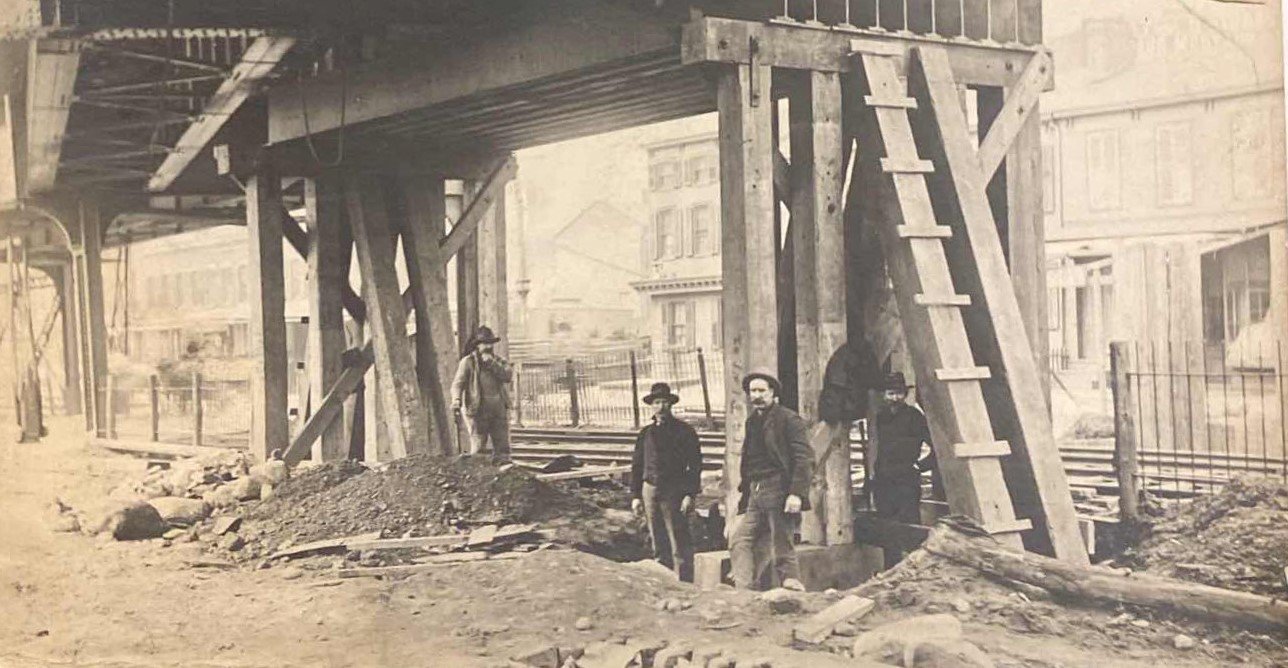

Eventually, the mayors of Brooklyn and of New York, the railroad and the state agreed to share the cost of an Atlantic Avenue Improvement, a massive public works project to separate the LIRR trains from traffic in viaducts and tunnels, all the way to the Brooklyn border. Atlantic Avenue’s railroad would be electrified, and “an uncommonly high rate of speed will be attained,” the railroad promised.

That “high rate of speed” meant New York City’s commuter zone was again shifting east. This news would bring asphalt and subdivisions to thousands of acres of farms between East New York and Jamaica. Buyers were promised fresh air and rural scenery in these new “residential parks” — Brooklyn Hills, Chester Park, Ozone Park, Brooklyn Manor, Union Terrace, Columbia and Belmont Parks, and others.

And when, in 1908, the Atlantic Avenue Improvement had replaced steam trains with electric ones, and the IRT connection with the LIRR was complete, Brooklyn held a torchlight parade to celebrate. At Jamaica’s three-day festival, real estate men calculated the new electric service would save commuters about five years of their lives.

Atlantic Avenue looking East from Bedford Ave. after electrification. History of the Atlantic Avenue Improvement, 1907. Municipal Archives.

“The center of political power is destined to move from the Borough of Manhattan to the Boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn,” New York Gov. Charles Evans Hughes told the Jamaica crowd.

Left unmentioned was that almost all Atlantic Avenue’s Brooklyn stations had just been eliminated, leaving only Nostrand Avenue and East New York. For the most part, this railroad, born in Brooklyn, had become somebody else’s ride to work.