Long Island Dirt: Long Island: Understanding the Place and its People

Long Island Dirt:

Recovering our Buried Past

by Allison McGovern

Long Island:

Understanding the Place and its People

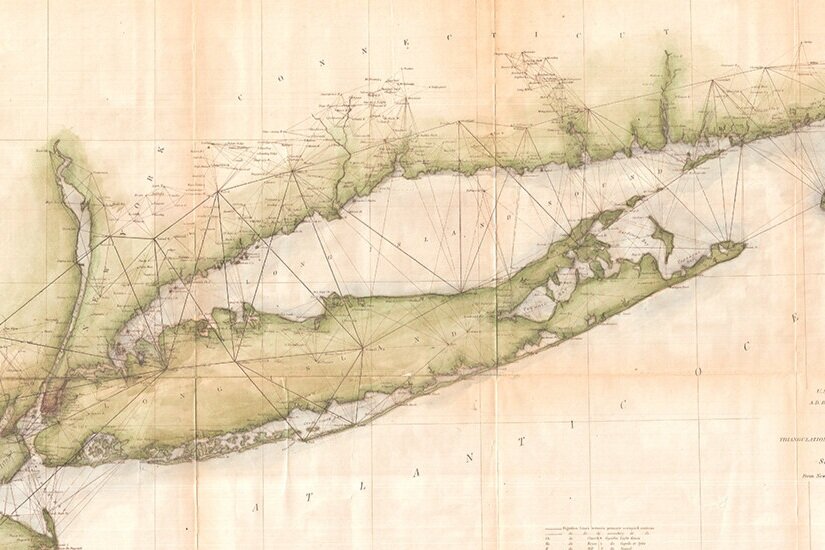

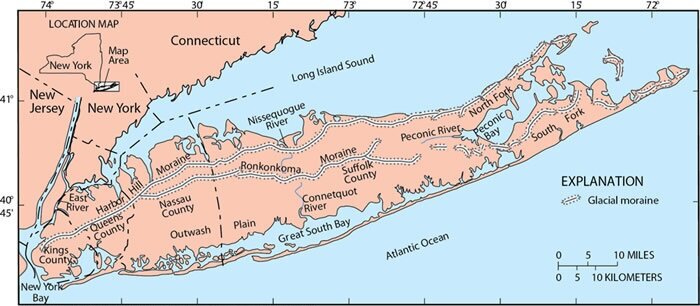

Located in the downstate region of New York, east of New York City, Long Island is an island measuring roughly 120 miles in length and 23 miles at its greatest width. The eastern third of the island is split by two peninsulas: the North Fork and the South Fork. The shape resembles a fish with the two forks forming its tail. The topography reflects the island’s geological formation from glacial movement and coastal erosion. High topography and rocky beaches characterize much of the north shore of Long Island, while the sandy outwash plain and beaches represent the lower topography of the south shore. Glacial retreat left its mark throughout the interior of the island as well, with relatively flat plains, lakes and ponds that were formed from the maximum retreat of the Wisconsin ice sheet more than 18,000 years ago. Humans have always established their settlements in interesting and meaningful ways in relation to these features. And if you ask any resident of the island today, whether you’re from the North Shore or the South Shore, the North Fork, the South Fork or “up island,” there are clear distinctions in meaning and identity to Long Island’s different places.

As you travel east from New York City toward the ends of the two forks, the landscape changes dramatically from the urban landscape of the metropolitan area to a suburban landscape that seems to spread out spatially the further east that you go. There’s no sense of overall planning to Long Island’s settlements, as each of the towns and communities that you drive through seem to have developed from their own sense of place in history, and that sense of community and pride of place is widely known among Long Island residents.

Geographically, the island comprises four counties: Queens and Kings (Brooklyn) counties in the western portion of the island; Nassau County is east of Queens County, and Suffolk County is east of Nassau County. But culturally, Long Island includes only Nassau and Suffolk counties. Brooklyn and Queens are two of the five boroughs that comprise New York City, and that invisible border that separates the city from Nassau County is a strong marker of personal and community identity.

Localism

Long Island is characterized by an intense sense of localism within its many communities in Nassau County and Suffolk County. This sense of belonging to a local community is strengthened by the way school districts, emergency services, and other public services are organized within communities. Rather than depending on larger political jurisdictions for services, Long Island’s communities function autonomously, and their power has led to pride of place among their residents. While many scholars attribute this sense of localism to mid-twentieth century suburban growth (especially regarding white residents who fled urban centers as immigration and racial integration created more heterogeneous populations), history suggests that the desire to develop autonomous communities can be traced back centuries to the arrival of Long Island’s first European settlers from colonial settlements in southern New England. And deeper still in history, there is evidence that Long Island’s ancient indigenous residents were locally focused in their settlements, too.

Perhaps one of the most significant moments to fuel Long Island localism was the creation of Nassau County, the western of the two counties that comprise the Long Island cultural region. Prior to 1899, the towns that make up Nassau County were part of Queens County. Queens, Brooklyn, and Suffolk were among the twelve original English counties established in the Province of New York in 1683. As the population of the New York City region swelled and the landscape became more urban into the nineteenth century, there arose an interest in consolidating the urban areas. In 1898, New York City annexed Queens County, but the county’s three eastern towns—Hempstead, North Hempstead and Oyster Bay—seceded and formed Nassau County. These areas were considerably less urban than the western portion of Queens County at that time, and the population had deeper historical roots. The towns that comprise Nassau County were defining their sense of place and community identities in contrast to the changing urban landscape of New York City that witnessed an influx of immigrant arrivals.

Regionalism

Even though Long Island communities tend to be locally focused, that does not mean that Long Islanders’ lives are controlled by fixed, local boundaries. In fact, Long Islanders are constantly crossing borders—for work, for school, for shopping and services. They are tied to regional economies, markets and work forces, just as they are integrated into global markets, politics and cultures. Perhaps the most significant region to which Long Islanders are connected is the metro-New York region, which includes the five boroughs of New York City, as well as Connecticut and New Jersey, comprising the tri-state region. These regions are connected by a series of tunnels and bridges which facilitate boundary crossings by car, but also by public transportation. Ferries are also important transportation systems in the bays and channels surrounding the island. In their daily lives, people are crossing boundaries and engaging in a variety of networks in which they are demonstrating and navigating their identities. While Long Islanders are particular in their sense of place, their experiences are also diverse and fluid as they move into different situations and settings, often without recognizing their adaptions to new experiences. This is the complexity of the human experience.

All of this is to say that Long Island identity is tied up within a series of boundaries and relationships that are not so easily understood from outsiders. And this interests me, as an anthropologist and a historian. I’m interested in the complexity of human lived experience, and I’m interested in how our understanding of the present can be informed by the past. There is no single, homogenous landscape on Long Island. And there is no single, homogenous lived experience for people on Long Island. Archaeology is one of the ways that we can explore this diversity of ecology and human experience.

Long Island’s People

Long Island’s earliest inhabitants date back tens of thousands of years when Long Island wasn’t even an island yet, and the land extended out to the continental shelf. Material (archaeological) traces are few and far between from those earlier times, and we would expect more than a few artifacts from coastal settlers during this period to have been submerged from sea level rise, now buried on sea floors off the coast. The histories of those past peoples are recorded in indigenous origin narratives, remembered by modern tribal groups on Long Island and throughout southern New England. These were the lands of the ancestors of contemporary indigenous people and tribal groups—the Shinnecock, the Unkechaug, and the Montaukett, to name a few.

The indigenous ancestors settled along the rivers, creeks and coasts throughout Long Island and southern New England. They were speakers of the Mohegan-Pequot-Montauk Algonquian language and they maintained a foraging lifestyle, intensively relying on marine and estuarine resources for thousands of years prior to European arrival. People were connected throughout the region by shared cultural patterns, mutually intelligible languages, and kin connections that continued for thousands of years, and continue today.

Archaeology has always been a means for documenting and understanding ancient indigenous lifeways in northeast North America. But archaeology has also contributed a particular perspective or framing of the indigenous past—as ancient peoples, frozen in time, disconnected from contemporary indigenous peoples, and the subject of scientific investigation. As archaeology began to develop as a method for collecting and understanding the past in the 18th and 19th centuries, there also developed a tendency to consider the remnants of ancient indigenous cultures as distinct from the living indigenous and tribally-organized people of North America. The idea that the “prehistoric Indians” lost their culture and disappeared was developed during the early years of archaeology and has since persisted in local historical narratives and exhibits, as it has been internalized through subsequent generations of Long Islanders.

When Europeans arrived, they encountered indigenous people and groups throughout the Long Island region. According to the history of the Montaukett Indian Nation, all of Long Island east of the present-day Queens County line was occupied by the Algonquian Native Nation called Matouwac or Montaukett prior to 1637. This was neither a “tribe” (as the socio-political type is defined) nor a confederacy. Indigenous people were settled throughout the region in groups based on kin, and they would come together to defend themselves against a common enemy.

In contrast, local residents know the Montaukett as one of “the thirteen tribes of Indians” that occupied Long Island at the time Europeans arrived. This myth, though taught in schools and repeated in local histories, presents Native American socio-political formation incorrectly and masks the realities of cultural and economic continuity that is highlighted in the archaeological record. Recent historians and archaeologists recognize this myth of “the thirteen tribes” as problematic because it is not history that was recorded or retold by indigenous historians but was instead developed by nineteenth century white historians more than 200 years after Europeans arrived on the shores of Long Island. And yet, archaeologists and historians alike continue to perpetuate this fiction of “the thirteen tribes” in their writing and exhibits.

When Europeans arrived on the shores of Long Island and the surrounding region, they came with people of African descent—mostly captives of the transatlantic slave trade. This was the time of global expansion through transatlantic travel and trade, and it brought diverse groups of people from Europe and Africa into the so-called “New World” of North and South America.

In the Long Island area specifically, people of Dutch heritage settled in western portions of Long Island, and people of English heritage settled in eastern Long Island by way of Connecticut and Massachusetts. These European settlers, some of them with captive African descended people in tow, encountered indigenous inhabitants throughout the island. Their interactions resulted in new relationships and connections throughout the region: labor networks, kin networks, and social networks. By exploring these networks, we can “connect the dots” between families or kin patterns, settlements, and site-based histories.

Immigration has been a significant factor in understanding Long Island’s local and regional histories. For hundreds of years following European arrival, immigrants arrived from throughout Europe, African and Asia—as captives and indentured laborers, and as freed men and women seeking new opportunities—and settled in various neighborhoods and communities throughout Long Island. These arrivals laid the foundation for diverse communities, and their stories are central to understanding Long Island’s history.

![[Willem Blaeu], NOVA BELGICA ET ANGLIA NOVA. [Amsterdam, 1635/1640]. Courtesy of the Library of Congress](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1634230362633-90PWO174HRYYBVNCU7NE/BRM3947-Blaeu-Nova-Belgica-1635_lowres-3000x2436.jpg)