When Long Island City Was the Next Big Thing

By Ilana Teitel

For about a hundred days this winter, Long Island City was in the spotlight as a neighborhood about to be transformed. Amazon was coming, the national media was running articles about the 7 train, and brokers were selling condos via text messages. The word was out about this patch of western Queens and its waterfront views, central location, cultural diversity, and overtaxed infrastructure.

And then, on Valentine’s Day, it was over. Amazon pulled out and locals began to debate whether that much change would have been good or bad for LIC. But, this wasn’t the first time that Long Island City was the neighborhood that almost, maybe, soon, was about to take off. Here’s a look at three other times that LIC was briefly New York’s Next Big Thing.

New York Magazine's 1980 coverage of Long Island City's bright future.

In 1852, the New York Times had a message for its female readers: Queens was underrated, fancier than Broadway, a great place to explore, and worth the trip from Brooklyn. “There are charming residences and delightful lawns at Ravenswood and Astoria,” said the paper of record as it urged people to take long walks to Astoria. “It is lamentable that with such fine weather and pleasant country promenades at hand, our fair friends, especially of Brooklyn and Williamsburg, do not avail themselves of their privileges. They would find an agreeable change from the usual hackneyed routes…Throw off this deathly indolence that is benumbing your physical and spiritual faculties”[1]

Jeff Bezos wasn’t the first wealthy industrialist to know a pretty stretch of waterfront when he saw it. Those “charming residences” the Times described were country estates that lined the neighborhood of Ravenswood, which straddles the border between Astoria and Long Island City. Homes with names like Bodine Castle and Mount Bonaparte served as getaways for rich Manhattanites. Long Island City was far enough away from the crowding and diseases of the city to feel like an escape. Then, as now, ferry service provided a quick commute to Wall Street.

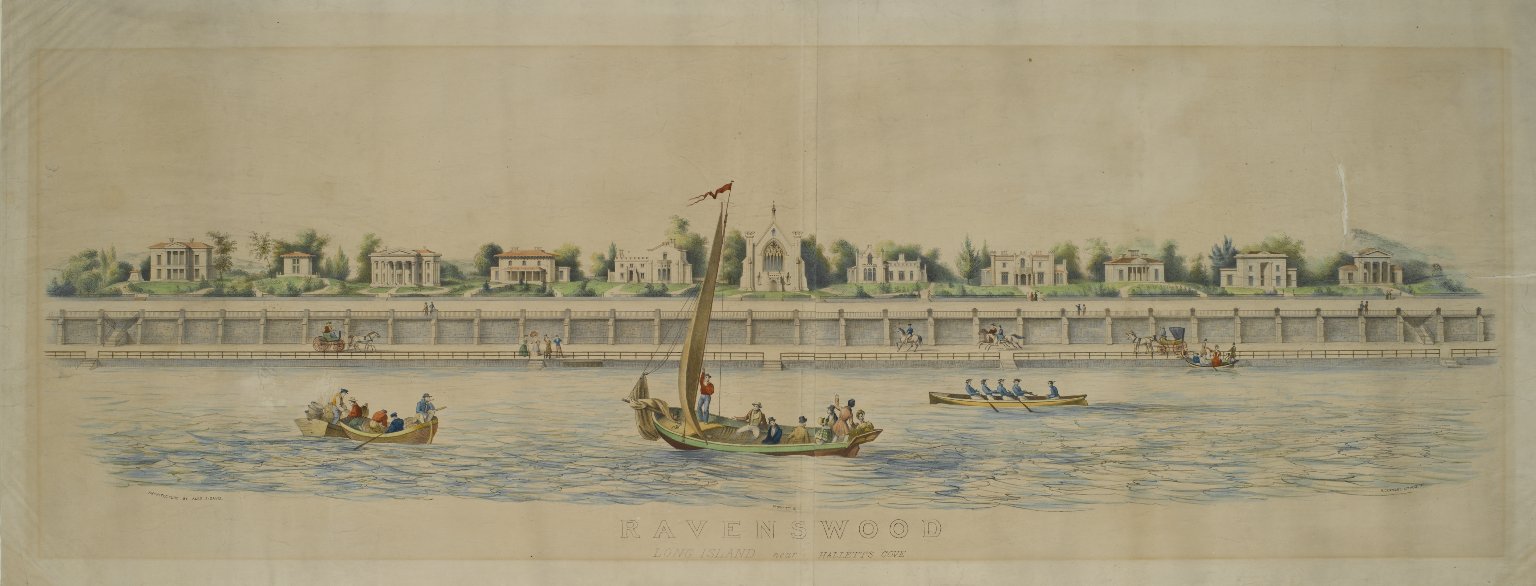

A 19th Century Currier and Ives print depicts mansions on the Long Island City waterfront.

A nineteenth century Currier and Ives print of these Ravenswood villas shows the waterfront promenade that the Times was urging its “fair friends” to explore. Long Island City did indeed have great places to visit. It was off the beaten path, but still accessible by public transportation. But, apparently, even in the 1850s, that just wasn’t enough to convince most people to make the trip out to Queens.

What finally got people to go to Long Island City was a decision by the City of Brooklyn to ban steam locomotives in 1861. Instead of switching to less polluting trains, the Long Island Railroad moved its terminus to the Hunters Point section of Long Island City. What followed was an explosion of industry, commerce, entertainment venues and crowds in Long Island City.

Long Island City became a hub for produce from Long Island’s farms headed to Manhattan. Factories and tanneries and gas plants sprang up along the waterfront. Hotels and taverns opened to serve the travelers passing through the area. Soon the area’s breweries and bars became destinations unto themselves.

The Queens waterfront was no longer a quiet oasis for the rich. By the turn of the century, many of Astoria’s estates had been torn down as New York’s aristocrats moved to Long Island’s Gold Coast.

Not all the locals were happy with the rapid growth or the neighborhood’s newfound popularity. The Times weighed in again, noting that “the turbulent characters of New York and Brooklyn who swarmed over the river and creek on Sundays could not be controlled and consequently Hunters Point has gained an unenviable notoriety.”[2] Things got so out of hand that in 1867 a committee of local stakeholders formed to make sure that the neighborhood’s infrastructure could keep up with the rapid pace of development. Their first decision was to take up a collection to build a “lock-up” so that the local constables wouldn’t have to transport disorderly prisoners. A local real estate speculator named Henry S. Anable offered to donate land for the jail. Today, he’s remembered more for being the namesake of Anable Basin, the short-lived site of Amazon’s HQ2.

Long Island City’s next period of popularity came in the early 20th century. The opening of the Queensboro Bridge and new, elevated subway lines made Queens a much easier commute. Once again, the Times praised the borough, urging “the man who is seeking better and less expensive accommodations" to check out apartment listings in Queens[3]. Developers were snapping up farmland and the very last of Astoria’s grand estates. New rowhouses and small apartment buildings like the Matthews Models flats housed immigrants and factory workers. The population of Western Queens soared.

More factories and new offices opened near the bridge and the subways. And the area became busier and more congested. Traffic in the area became so bad that the police instituted no-parking zones on some of the more popular streets. “The practice of motoring to lunch at Queens Plaza will have to cease” said one article, “and Long Island City businessmen may no longer park their cars near the restaurants in that district.”[4]

Once again, Queens residents began to demand infrastructure improvements and better planning. Queens was New York’s fastest-growing borough, but its future was dependent on solving transportation problems. In 1929, the Regional Plan Association released its Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs. It was the first comprehensive long-range plan for the entire metropolitan region. And it had some big ideas about Long Island City’s place in a city designed for the future.

The plan proposed turning Queens Plaza into a modern transit hub. Drivers would navigate through the area on remapped streets, with elevated roadways above and open plazas below. A large “motor parking hotel” would let commuters leave their cars in Queens and take the train into Manhattan.

A 1929 plan for decking over Sunnyside Yards.

But the Regional Plan Association had one truly grand and ambitious idea to transform Long Island City--they wanted to deck over the Sunnyside Rail Yards. The sprawling rail yard opened in 1910, the same year that the Pennsylvania Railroad began running trains under the East River and into the newly built Penn Station. And because most rail traffic had been routed through Queens ever since Brooklyn first cracked down on steam engines, the world’s largest rail yard was located just east of Queensboro Plaza.

About a century before the Atlantic Yards project brought the Barclays Center to downtown Brooklyn or the Hudson Yards’ Shed and Vessel transformed Manhattan’s far west side, the 1929 regional plan proposed Sunnyside as a mega-project over a railyard. A modern, streamlined “Skyscraper Terminal” would consolidate access to the region’s twisted network of subway and rail lines, and serve as an anchor for growing neighborhood.

The Great Depression paused these plans. Now, almost a hundred years later, a new commission is once again proposing that the city build over the Sunnyside Yards.

Long Island City stayed fairly stable for the next fifty years--a place full of warehouses, factories, industrial sites and low-rise housing. And then, in August of 1980 New York magazine splashed a glossy photo on its covered and declared Long Island City “The Next Hot Neighborhood.” A lengthy article profiled real estate speculators, artists, entrepreneurs, and savvy Manhattanites who’d made the trip across the river on the 7 train. They gushed about the neighborhood’s low prices and great location: “It’s Soho-plus, with the East River waterfront thrown in.”[5]

This was when people began to speak of “pioneers”--those daring people who visited Long Island City to see the work of avante garde artists and dine at authentic ethnic restaurants. Industry was dying in the city and the neighborhood was full of empty factories and warehouses. Some of the projects the article highlighted did get built and are still around today, like Silvercup Studios and MoMA P.S. 1. A floating barge restaurant that the magazine gushed about flourished for many years on the inlet where Amazon almost built that was named for the man who built the neighborhood’s first lock up.

And then there was QP’s Marketplace. Again, maybe Long Island City was just ahead of its time. A few decades before Smorgasburg and Brooklyn Flea, way before standing in line for food trucks and handmade crafts became what everyone did, there was a weekend flea market in Queens Plaza. It was conceived as part farmer’s market, part designer outlet, and part food wholesaler, with some vendors selling goods straight out of railroad cars that rolled right up to the market’s main building, which was converted from a former chemical plant.

The impetus for QP’s founders was to show off the area’s potential to both bigger retailers and upscale shoppers from around the city. The reality was a teenager’s paradise. The market was a warren of twisted hallways and small stalls hawking all sorts of cheap 1980s merchandise: baggy sweatshirts and cheap leg warmers, cassette tapes and comic books, plus junk food.

In the years since that 1980’s hype, apartment buildings and office towers have transformed Long Island City. There’s a new glass tower now on the site of the chemical factory turned flea market. Not far away, there’s a trendier 21st century flea market in LIC whose immediate future seems secure now that Amazon isn’t taking over the site. The waterfront views are still fantastic, and Queens Plaza is still in need of an overhaul. Let’s see what the next big plan brings.

Ilana Teitel is a writer and community advocate who is a longtime Astoria resident. More of her writing about Queens can be found at Medium.

Notes

[1]“Walks, “New York Daily Times, October 20, 1852.

[2]“Long Island City—Its Growth and Prospects,” New York Times, May 8, 1870.

[3]“Apartment Growth in Queens Borough,” New York Times, May 5, 1929.

[4]“Bar Queens Plaza Parking,” New York Times, November 19, 1926.

[5]Bob Keating, “The Next Neighborhood,” New York, August 11, 1980.