The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902: Immigrant Housewives and the Riots that Shook New York City

Reviewed by Aaron Welt

In May of 1902, social unrest erupted on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the neighborhood with more Jewish immigrants than any other in America. The roots of the agitation lay eight hundred miles west in Chicago, where the “Beef Trust,” four massive corporations that dominated the country’s supply of meat products, imposed a steep rise in prices, including for kosher items bound for Jewish New Yorkers. Meat wholesalers, powerful entities themselves, passed the added costs onto Gotham’s hundreds of retail kosher butchers, modest business concerns owned by people who lived in the same tenements as the Jewish immigrant clientele they served. Over the early part of May, much of the kosher meat trade in the nation’s largest city came to a standstill, as many Jewish abattoirs refused to fleece their neighbors.

The kosher butchers who chose to remain open soon encountered trouble. Jewish immigrant housewives throughout the Lower East Side, as well as in Brownsville, Harlem, and the Bronx, organized a boycott of kosher beef under the auspices of the “Ladies Anti-Beef Trust Association.” Jewish women activists fanned out across the neighborhood, imploring locals to abide by the boycott, or the “strike,” as they often called their campaign, until the price of meat went back down. But not all residents of the Lower East Side agreed to join the collective effort, leading to scenes of chaos and even violence. During the “Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902,” as the late historian Paula Hyman called the event, some Jewish women attacked “scabs” who continued to buy kosher meat, ransacked and vandalized butcher shops, and scuffled with police who responded with heavy-handed brutality. The kosher meat boycott — or strike, or riot, or war — lasted only a month, but the memory and legacy of this event stands out in the annals of American Jewish history.[1]

In the one hundred-twenty years since the Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902, a number of intellectual giants have offered thought-provoking interpretations of this remarkable moment. Because the dominant players were housewives and not formally employed in factories, histories of the Jewish labor movement have largely glossed over the event. But in 1977, Herbert Gutman, the pioneering social historian who helped introduce “history from the below” into studies of the American working class, invoked the violence of May 1902 in a New York Times op-ed following the harsh censure of looters in the aftermath of that year’s power outage and blackout. Hyman, a trailblazing scholar of Jewish women’s history, broke new ground three years later with her landmark article, “Immigrant Women and Consumer Protest: The New York City Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902,” an essay that adeptly incorporated Gutman’s tools of social analysis. The uprising of Jewish housewives has likewise attracted the scholarly attention of some of the leading historians of American Jewish history, particularly of American Jewish women, who have correctly identified the kosher meats riots as a historical episode that upends conventional understandings of how gender, capitalism, and power operated among American Jews during the era of mass migration to the US.[2]

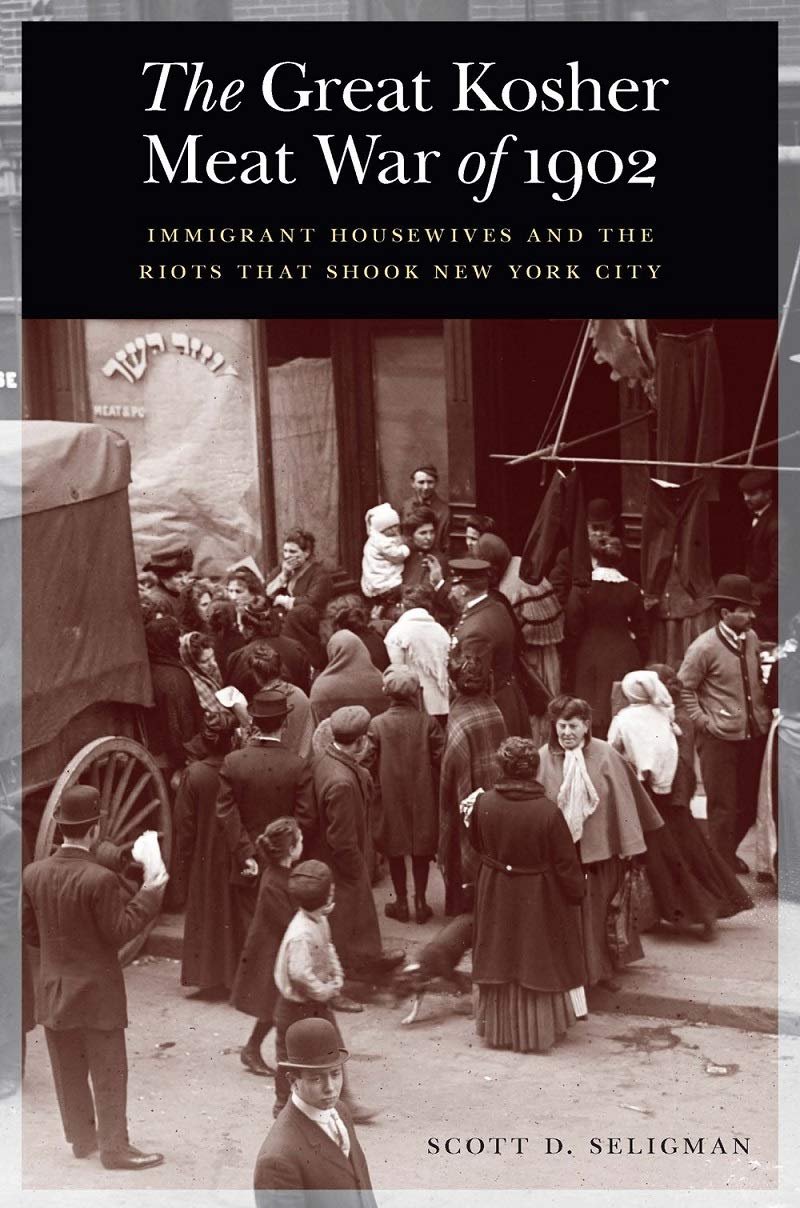

With The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902, Scott D. Seligman offers the first book-length treatment of the campaign of Jewish housewives against the “Beef Trust.” For readers familiar with Seligman’s prior works on Chinese American history, the narrative arc of The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902 will feel familiar. Seligman provides a highly readable chronology of the events between May and June of 1902 that, at the time, earned the title of “a modern Jewish Boston Tea Party” and, later, the Kosher Meat Boycott. He succeeds in bringing to life the largely forgotten and primarily female leaders of the consumer campaign, their roles within the collective effort to bring down the price of kosher beef, the internal divisions that developed, and their significance for American Jews. Largely constructed from media portrayals in both the English and Yiddish press (which covered the event feverishly), Seligman uncovers new details about the kosher meat riots that complicate older ideas about American Jewish women. Seligman gives readers a clear and comprehensive account of how the boycott, which he terms a “war,” arose, unfolded and declined, but also lived on in future political campaigns.

The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902 provides vivid and intimate portrayals of the central actors who did the hard work of organizing a largescale consumer boycott amid the relocation of nearly two million Jews to America. In the opening pages, the reader meets Sarah Edelson, a Russian Jewish immigrant living on the Lower East Side, a pious woman and “a force of nature” whose pluck and savvy initially got the boycott up-and-running following the Beef Trust’s abrupt price increase. Edelson was soon joined by Caroline Schatzberg, a Romanian Jewish immigrant who evinced remarkable skills in community organizing in bringing the Ladies Anti-Beef Association into existence and recruiting hundreds of fellow Jewish housewives into its ranks. Schatzberg’s experience, Seligman reveals, conveyed the powerful social and cultural forces working against these women during a period in which Victorian ideals dominated and American women had not yet received the Constitutional right to vote. At the Educational Alliance, an influential Lower East Side charity, the resident rabbi Adolph Rudin adamantly refused to back the housewives’ movement, tarring Schatzberg as a “beast,” and lobbied city authorities to deny the Ladies’ Anti-Beef Trust Association the permits required to hold street demonstrations (125). This highlights an important historical point that Seligman skillfully showcases: the Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902 reflected the formidable divisions within American Jewry. Indeed, by the end of campaign, even Edelson and Schatzberg turned from allies into bitter rivals (152).

Another triumph of The Greater Kosher Meat War of 1902 is Seligman’s positioning of the event within the emerging Progressive Era of the early twentieth century. Prior treatments of the boycott have focused more narrowly on its specifically Jewish dimensions. But Seligman convincingly demonstrates that the kosher meat boycott emerged from broader, national economic forces and spoke to larger political concerns that affected all Americans. The Beef Trust’s seemingly arbitrary price hike almost immediately drew the spotlight of Progressive activists. It even attracted the attention of none other than President Theodore Roosevelt who, at the time, was beginning to articulate his vision of a “Square Deal,” or an activist government regulating big business on behalf of the American public. Shortly before the boycott in Jewish New York, Roosevelt had directed Attorney General Philander Knox to look into the Beef Trust, leading to an extensive Justice Department investigation that uncovered a litany of corporate abuses commonly practiced by the nation’s “trusts” and “robber barons.” A legal campaign against the meat kingpins followed, which resulted in an injunction preventing the Beef Trust from colluding on prices, restricting competition, blacklisting non-cooperative business, and violating the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Yes, the brave activism of the Ladies Anti-Beef Trust Association helped to bring the price of kosher meat back down by June of 1902. But, Seligman shows, so too did federal government intervention, the type that would come to define the emerging liberal politics of the Progressive Era.

Throughout The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902, the author refers to the “balebostes” behind the boycott, a Yiddish word that can be interpreted as “housewives.” A more literal translation of baleboste is “master of the house,” a term with real resonance in Jewish history. In the Russian Pale of Settlement, where many of the immigrants whom Seligman discusses came from, Jewish society was strictly patriarchal in matters of religion and politics. But as some historians have pointed out, these patriarchal norms, ironically, opened up a number of important opportunities for Jewish women in the shtetlach (small cities) of the Pale of Settlement. With religious scholarship and study the domain of Jewish men, some have argued, women, including those from the lower classes, found an opening to work in, and even manage, small businesses. Historian Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern has even argued that Jewish families in the Pale were “entirely matriarchal.”[3] It was this historical experience of Jewish women that set the stage for the kosher meat boycotts.

The women at the heart of Seligman’s study carried with them these traditional cultural and gender norms, belying his claim that “whatever relevant experience these women might have brought with them when they crossed the Atlantic, resistance in America called for breaking out of traditional roles and employing unfamiliar tactics (x).” The case of Sarah Edelson is especially revealing. As the author reveals, Edelson was born in the Pale of Settlement in the 1850s, during the period when Jewish women assumed the vital economic functions suggested by the term “baleboste.” Seligman uncovers that after the Edelsons shipped off to New York in the late 1860s, Sarah worked side-by-side with her husband, Joel (who, at one point, labored as a kosher butcher), in a Lower East Side saloon. Hers is a story of a trans-Atlantic Jewish woman displaying historically-informed perspectives and behaviors that assisted Jewish women in navigating the political economy not only in the Russian Empire but also in Gilded Age and Progressive Era America. It was Sarah Edelson’s traditional culture that provided her a blueprint for how to politically organize other Jewish women who shared a similar ethnic background and, likewise, felt their rights violated when the Beef Trust trampled on their ability to manage their family budgets.

In contrast to Herbert Gutman, Seligman is wary of placing the kosher meat boycott in New York City’s larger social history. Gutman felt compelled to conjure the Jewish housewives as the city’s press indulged in a frenzy of highly racialized condemnations of the “vultures” and “predatory animals” behind the 1977 looting, which occurred against the backdrop of the city’s decade-long urban crisis and fiscal insolvency. Seligman, conversely, takes every opportunity (sometimes awkwardly) to denounce the violent tactics of some of the Jewish housewives. The author does assert that the rioters of 1902 exhibited “discipline,” which made their experience “unlike the case in many urban riots,” in which there is “collateral damage.” Nevertheless, in the afterword, he chastises the women activists who wielded physical force (in defiance of the movement’s leadership), claiming that the violent methods were “the only real mistak[e]” that the Jewish housewives made (239).

Seligman has nonetheless produced an important contribution to the scholarship on the Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902, as well as American Jewish women’s history. He succeeds in urging the reader to learn about and ponder the lives of ordinary Jewish women like Sarah Edelson, Caroline Schatzberg, Paulina Finkel, and dozens of other brave women activists who, despite the odds, stood up to powerful corporations, mobilized their neighbors and local communities, sacrificed their time, effort, and well-being with no guarantee of success — and, through patience and persistence, won.

Aaron Welt is a doctoral lecturer at Hunter College, CUNY, who teaches courses on American Jewish history.

[1] Paula Hyman, “Immigrant Women and Consumer Protest: The New York City Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902,” American Jewish History 70, No. 1 (1980): 91-105.

[2] Herbert Gutman, “As For the ’02 Kosher-Food Rioters …,” New York Times, July 21, 1977, 23; Susan Glenn, Daughters of the Shtetl: Life and Labor in the Immigrant Generation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), 176; Hadassa Kosak, Cultures of Opposition: Jewish Immigrant Workers, New York City, 1881–1905 (Albany: SUNY Press, 2000), 143-44; Hasia Diner, Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, & Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), 206.

[3] Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, The Golden Age Shtetl; A New History of Jewish Life in East Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 219.