The Great Epizootic of 1872: Pandemics, Animals, and Modernity in 19th-Century New York City

By Oliver Lazarus

Monday, October 21st, 1872, began like many mid-fall days in New York — overcast and muggy with spitting rain, and a high of sixty-six degrees.[1] There were several plays at uptown theaters, a championship baseball series at the Union Grounds in Brooklyn, and political speeches in advance of the elections next month. President Ulysses Grant, seeking re-election that fall, was in town with his wife to meet their daughter, Nellie Grant, who was returning from Europe, and to attend a performance of Charles Gounod’s “Faust” at the Academy of Music on E 14th Street.[2] Business was strong, with high trading in the city’s markets and piers. All in all, the end of October appeared to be proceeding normally.[3]

New York City had expanded considerably in the years since the Civil War. The city had come to dominate nearly every sector of the US economy, helping to drive a national post-Civil War surge in commerce, manufacturing, and finance. The city’s population had doubled from 500,000 in 1850 to around one million.[4] The city’s physical landscape was also expanding, with an increasingly complicated transportation network facilitating the construction of new residential neighborhoods in upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Westchester, among others. New York City was no longer just important nationally. By the early 1870s, the city had become the “Metropolitan City of the World,” generating a new form of urban capitalist modernity that became a global export in the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries.[5]

Fall was supposed to mark the height of business in the city, when commerce and trade peaked.[6] But as the week of October 21st dragged on, this seemingly unstoppable progress came to a halt. The streets of the city were without their usual torrent of traffic. Opera houses, baseball stadiums, churches, even political rallies two weeks away from a presidential election, were left empty. Workers across nearly every industry were unable to travel to work, leaving thousands without jobs. Untouched boxes piled up along the railroad depots and piers, among the busiest in the world. At a time when New York City was becoming more powerful and rich than ever, it reverted, for a brief period, to a pre-modern city.

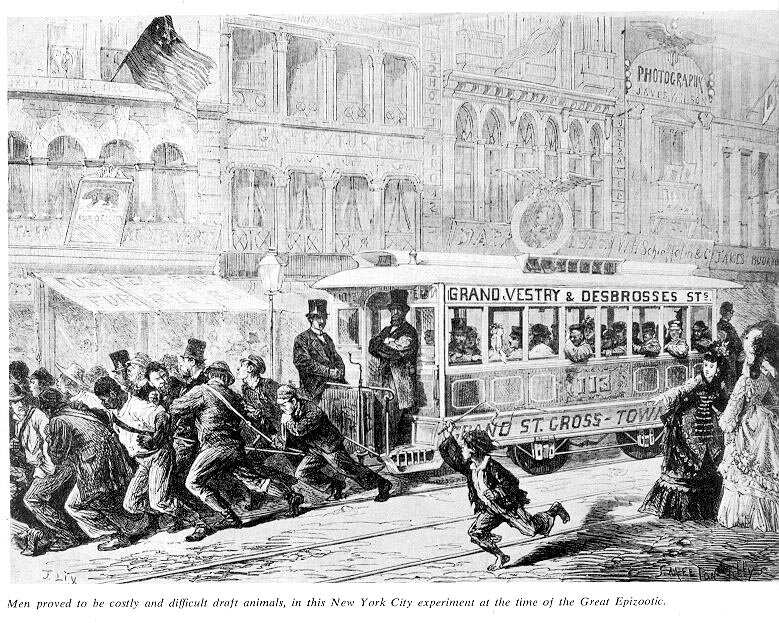

An “experiment” using men instead of horse teams at the time of the Great Epizootic, photo from The Brooklyn Historic Railway Association

The cause of this stoppage was an attack on what is often dismissed as a vestige of that pre-modern city, but what was arguably New York’s most important energy supply: horsepower. A disease, believed to be an influenza, reached the city on October 21st. Within a matter of days, it had affected the majority of the city’s estimated 70,000 horses.[7] The influenza was, for the most part, not fatal, and three weeks later the city returned to a state of relative normalcy. But what would come to be known as the “Great Epizootic” was debilitating enough to fundamentally alter the city, and reveal the significant ways in which the daily operations of the metropolis relied on an otherwise invisible labor force, horses, from local entertainment to international shipping.

Throughout October, the city’s newspapers had been covering an unknown disease that began afflicting horses in Canada in late September and was now as close as Rochester.[8] But there was no indication that horse owners, or anyone else in the city for that matter, actively feared that the disease would affect the city. That began to change on the evening of the 21st, when the first signs of the disease appeared in one of the many streetcar stables, then the city’s primary mode of transportation.[9] The initial symptoms were just a light cough, often confined to one or two horses in a stable. But within a matter of hours, the cough progressed into a more serious form, and eventually to what was described as a catarrhal fever. The disease was highly contagious, quickly affecting nearby horses. Once contracted, horses would refuse food and had difficulty moving. Entire stables of horses could be immobilized by the disease within a twenty-four-hour period.[10]

Many stable owners awoke to this dire situation on the morning of Tuesday, October 22nd. “I never saw anything like it,” one prominent banker and stable owner told The New York Herald. [11] The papers and businesses quickly realized the high stakes of the disease’s progression. The horse population had grown significantly over the course of the 19th century, and had particularly spiked in the decades after the Civil War.[12] By the early 1870s, people in the city were taking an estimated 100 million horse trips per year, mostly on the streetcar network, which expanded from six lines in 1860 to eighteen lines by 1875, carrying four and a half times more people.[13] The epizootic threatened to cut off this transportation network entirely, causing a “great panic” by Thursday, October 24th. By the end of the first work week of the disease, the city turned into a “vast horse hospital.”[14] Nearly all of the private vehicles were off the road, and the number of streetcars had been cut in half. Nonetheless, the recently formed Metropolitan Board of Health, which held a special meeting that Thursday, decided not to take action, confident that the disease would pass on its own.[15]

On Friday, October 25th, that outlook changed, when the number of sick horses jumped from 7,000 to 15,000, creating “a great feeling of dread.”[16] By Saturday, the newspapers described the number of horses affected as “impossible to estimate,”[17] even suggesting that the disease had crossed the species barrier and was now affecting humans and other animals, some reports of which were confirmed by the Board of Health’s review of the Epizootic in 1873.[18] As far away as San Francisco, reporters began to cover the disease in New York, initially focusing on valuable trotting horses who had fallen sick, such as Ethan Allen Lincoln, Stonewall Jackson, Lady Wheeler, and Captain Jinks, some of whom were worth over $15,000 and whose outings were frequent topics of conversation.[19] But the disease was equally debilitating for horses outside of high society, who formed the backbone of the city’s business network. With about a quarter of the city’s horses sick by October 26th, streetcar companies were losing over $2,000 a day.[20] Henry Bergh, president and founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, began patrolling the streets to remove working horses that he deemed unfit for work.[21] But horses were not just essential for transportation. Nearly every business and individual relied, at some point, on horsepower, for construction materials, freight deliveries, mail, trash, firefighting wagons, power supplies, even the removal of dead horses.[22] By the end of the first week of the disease, life in the city had been reduced to a trickle.[23]

The Great Epizootic reached the height of its effects in New York City in the final days of October and early November, when the streets “were still as empty as the ancient tombs of Egypt.”[24] From stopping transportation and cartage, the disease’s impacts grew to touch nearly every aspect of business in the city, and consequently around the country. “[E]ffect on local travel and on all branches of trade, is depressing beyond precedent,” affecting “every individual” in the city, noted The New York Times.[25] A report filed by a New York reporter to The Chicago Daily Tribune on October 29th suggested that the “derangement” of business was growing increasingly serious by the day. Piles of freight were beginning to accumulate at the city’s railroad depots and on its piers, as well as those across the river in Brooklyn and New Jersey. Even if shipping companies were willing to pay exorbitantly high prices, at least double normal costs, it was often the case that the towns on the receiving end couldn’t handle goods because of the disease’s effects in other towns along the East Coast, and eventually around the country; it was common for towns to put up signs announcing, “No more goods received.”[26] City services had likewise been severely affected. Only two of the fire department’s fleet of 150 horses were still healthy by the second week of the disease. Horse bodies, usually quickly picked up, were left to decompose for days.[27] The real estate market had experienced a “decided falling off.”[28] In outlying areas like Westchester, some questioned the viability of the suburban project without horse travel.[29] People were beginning to lose jobs. A reporter in New York City wrote in the Manchester Guardian how at a time of year with heavy trade, “Many thousands of persons were temporarily thrown out of employment, and there was scarcely an individual who did not feel the effects of the horse disease in one way or another.” The reporter continued, “New York was paralyzed by the horse disease something as Chicago was by the great fire, and when anything serious affects either of those cities the world speedily hears of it.”[30]

A sketch of the city during the horse plague by Theodore R. Davis, published in Harper’s weekly, 1872

There had been speculation that businesses in the city would use teams of oxen to fulfill inter-city transit needs. Some were quite bullish on this idea initially, with the Times speculating that the ox might take up “permanent residence” in the city.[31] About fifty teams of oxen were brought in via the Hudson River and became a common sight along Broadway and Canal Street. Other experiments included using steam engines on the streetcar lines, and allocating one to the fire department as well. Some streetcar lines were even pulled by teams of men strapped onto the front of the cars, a trip which cost sixteen times the usual fare. All of these solutions quickly proved ineffective, unable to fill the gaps left by horses.[32]

The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, the leading weekly business paper at the time, noted that all trade, from wood to tobacco, was lowered in both supply and demand. Washington Market, one of the city’s major commercial markets, was reportedly losing $50,000 a day.[33] Even Wall Street was affected. In addition to stocks for streetcar companies dropping in price over the first week, the Herald believed that the disease’s effects in the money markets prompted the Treasury Department to print more currency. Indeed, a total of about five million new greenbacks were issued at the end of October, a highly controversial move at the time.[34]

The end of the second week of the disease was the weekend before the 1872 presidential election, with President Ulysses Grant up for re-election against New York City challenger and owner of The New York Tribune, Horace Greeley. But the talk among horse owners, and in much of the papers, was the horse disease. Commenters began to wax poetic about the presence of the horse in New York City, and in society more broadly. On October 31st, The Nation wrote, “Our talk has been for so many years of the railroad and steamboat and telegraphy, as the great ‘agents of progress,’ that we have come almost totally to overlook the fact that our dependence on the horse has grown almost pari passu with our dependence on steam.”[35] On November 1st, the Herald noted, “What will be the effect of even a temporary withdrawal of the horse power from the nation is a serious question to contemplate.”[36] Greeley’s Tribune was particularly alarmist that day:

It is only when we are threatened with the loss of his services that we appreciate the extent of our reliance upon the horse. Without him we should gradually go back to the condition of Troglodytes. The transient suspension of his uses, next to scarcity of bread or an earthquake, is one of the most serious disasters which can befall a community.[37]

There was an increasing realization that without horses, 19th-century society, and its visions of grand national progress, would be fundamentally challenged.

But the disease was generally not fatal, and horses did not disappear, as many feared would happen. By the start of the third week of the disease on Sunday, November 3rd, enough horses had improved to the point where transportation and commerce began to pick up. The papers, which had been devoting wall-to-wall coverage to the disease, reduced their reports to a column. Despite fear that the presidential election on November 5th might have been affected by people’s inability to get to the polls, Grant won in a landslide, though it was possible that the disease affected down ballot races. Indeed New York State’s vote totals dropped off that year, the only such drop between 1856 and 1912.[38] Following the election, the streetcar lines were running at nearly full capacity, though with continued overcrowding. Oxen were leaving the streets, “with little prospect of being introduced again.”[39] By the weekend of November 9th, there was little mention of the disease, which resulted in the death of just under 2,000 horses in New York City, in the city’s papers.[40]

Mid-way through the disease’s progression, on October 31st, a reporter estimated that the commercial loss to New York City, ten days since it first arrived, was around six million dollars.[41] This amounts to $600,000 in losses daily. Extending that impact to the full two-and-a-half-week period when the disease was at its height, without including the cascading effects beyond this period as the disease spread to Central America and perhaps even Europe, results in $8.4 million in total losses.[42] Calculated for inflation, this translates to about a $180 million loss in today’s dollars.[43] This is, of course, a rough estimate, and obscures the critical non-monetary value that horse lives embodied in this period. But it provides some indication of the significance of horses to New York City in the late 19th century. The near absence of horses severely affected not only the city’s transportation network, but the very foundation of its daily functioning. During a period of rapid modernization, in a place that was becoming the mecca of capitalist modernity, the Great Epizootic put in stark relief that horses were not adjacent to the city’s rapid expansion into its present-day form. Rather, they were key both to the development of New York City, and arguably to the larger process of capitalist development. For two and a half weeks in 1872, the city did not become more “modern” without the presence of horses. In fact, the opposite happened; New York City was transformed into a shell of itself.

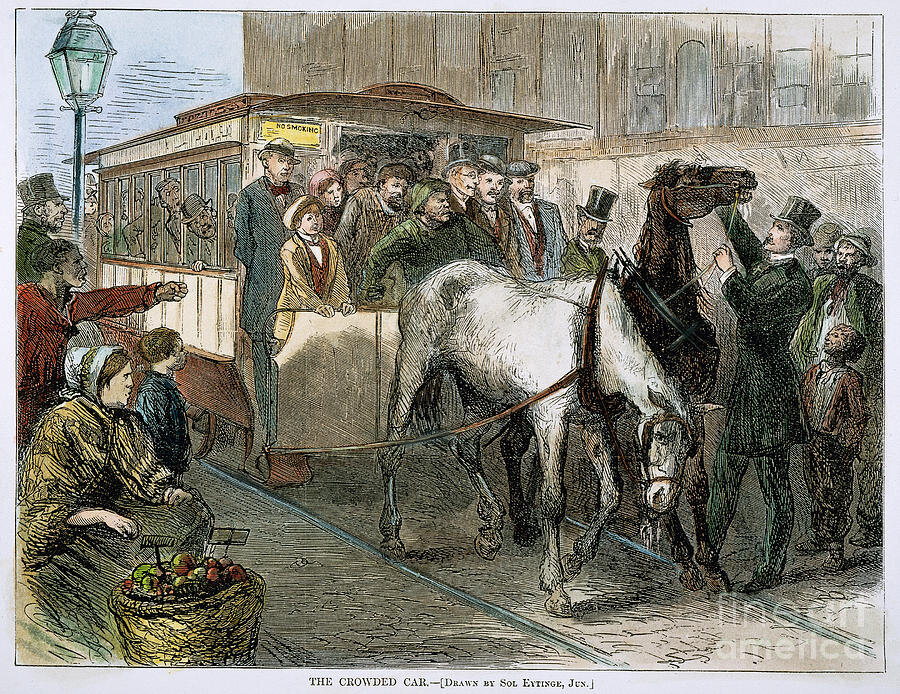

Sol Eytinge’ drawing of a pair of horses straining futilely against the weight of an overcrowded streetcar, from September 21, 1872 Harper’s Weekly

Amidst another pandemic, it is worth considering, too, what happened, and what didn’t, in the disease’s aftermath. At the start of the third week of the disease, a writer in the Herald pointed to the blatant cruelty that the Epizootic revealed at the heart of the city’s functioning: “Some time in the future,” he wrote, “the wondrously civilized and refined citizens of that time will remark upon the heartlessness of this period.”[44] He suggested that posterity might afford better treatment and more careful attention to an otherwise invisible, but essential, class of workers. But as the disease dissipated, these sorts of reflections also went with it. Meanwhile, the reliance on horses only grew in the episode’s aftermath, reaching a peak population of 130,000 horses in 1900 — a year also regarded as the height of the city’s national power. And the episode, which dominated conversation for weeks, with endless speculation over how the city might change in its aftermath, became little more than a curious blip.

Oliver Lazarus is a PhD student in Harvard University's History of Science Department. His work focuses on intersections of animal history and economic history, and how these interactions have shaped both material development and relationships with the natural world.

[1] “Meteorology,” Third Annual Report of the Board of Health of the Health Department of the City of New York: 1872-1873, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1873, p. 112.

[2] “President Grant in Town,” The New York Times, October 22, 1872.

[3] The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, 1 Nov. 1872, vol. 15, no. 384.

[4] Total and Foreign-Born Population New York City, 1790 - 2000. New York City Department of City Planning and Population Division, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/data-maps/nyc-population/historical-population/1790-2000_nyc_total_foreign_birth.pdf.

[5] Clifton Hood, In Pursuit of Privilege: A History of New York City’s Upper Class and the Making of a Metropolis. Columbia University Press, 2019, p. 90.

[6] The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, November 1, 1872, vol. 15, no. 384.

[7] “The Horse Disease,” The Manchester Guardian, November 15, 1872.

[8] “Report on the Origin and Progress of the Epizoötic Among Horses in 1872,” Third Annual Report of the Board of Health of the Health Department of the City of New York: 1872-1873, p. 253.

[9] “The Epizootic” New York Herald, October 23, 1872, p. 7.

[10] Third Annual Report of the Board of Health, 1873, p. 275.

[11] The New York Herald, October 23, 1872, p. 7.

[12] Ann Norton Greene, Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2008), p. 282.

[13] David Scobey, “Empire City: The Making and Meaning of the New York City Landscape,” Temple University Press, 2002, p. 81.

[14] “The Poor Beasts,” The New York Herald, October 24, 1872, p. 3.

[15] The New York Times, October 25, 1872; The New York Herald, October 25, 1872

[16] “The Diseased Horses,” The New York Times, October 31, 1872, p. 2.

[17] “The Horse Distemper,” The New York Times, October 26, 1872, p. 4.

[18] “Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times: The Epidemic Among Horses,” The New York Times, November 2, 1872, p. 4.; Third Annual Report of the Board of Health, 1873, p. 277.

[19] For more on the importance of horse culture to the city’s elite at the time, see: Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, “Chapter 54: Haut Monde and Demimonde” in Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). See also: Hood, In Pursuit of Privilege.

[20] “The Noble Horse in Peril,” The Sun, October 26, 1872.

[21] “Bergh's Botherations,” The New York Herald, November 5, 1872.

[22] For excellent analyses of the importance of horses to 19th century cities, see: Greene, Horses at Work. Clay McShane and Joel A. Tarr, The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century, Animals, History, Culture (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

[23] The Sun, October 26, 1872.

[24] “The Sabbath of the Steed,” The New York Herald, November 4, 1872, p. 9.

[25] “The Horse Plague,” The New York Times, October 27, 1872, p. 8.

[26] “The Horse Disease,” The Manchester Guardian, November 15, 1872.

[27] “The Horses,” The New York Times, November 3, 1872, p. 8.

[28] “Real Estate Market,” The Sun, November 4, 1872, p. 3.

[29] “The Future of Westchester County,” New York Daily Tribune, November 4, 1872.

[30] The Manchester Guardian, November 15, 1872.

[31] “The Coming Ox,” The New York Times, October 31, 1872, p. 6.

[32] Philip Guilibet, a writer for The Galaxy, was furious that no one was turning to the velocipedes, a precursor to the bicycle: “Dandies would as soon have ridden a rhinoceros down Broadway, or been carried in a palanquin — in fact, would gladly have bought elephants and hired bearers, had Indian customs been the go. But because, forsooth, it was no longer decorous to travel on the glowing axle, they left their flying tires to rust in carriage-houses, and footed it during the horse disease, that it might be fulfilled as it was written by Ovid, si rota defuerit tu pede carpe viam.” Guilibet, Philip, “Query,” The Galaxy, vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 1873, p. 129.

[33] “The Horse Disease: Special Dispatch,” The Chicago Daily Tribune, October 31, 1872.

[34] “The Horse Distemper: The Trade of the City and the Money Market,” New York Herald, November 4, 1872.

[35] “The Position of the Horse in Modern Society,” The Nation, as quoted in Greene 2008, pp. 1-2.

[36] “The Horse Epidemic,” The New York Herald, November 1, 1872, p. 7.

[37] The New York Tribune, November 1, 1872, p. 4.

[38] “Presidential General Election Results Comparison - New York, 1872.” Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Rhodes, James Ford. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Final Restoration of Home Rule at the South in 1877. Macmillan, 1912, p. 62.

[39] “The Horse Distemper,” The New York Times, November 8, 1872, p. 2.

[40] Third Annual Report of the Board of Health, 1873, p. 276.

[41] “New York: The Metropolis as a Silent City,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 7, 1872.

[42] Third Annual Report of the Board of Health, 1873, p. 270.

[43] “Inflation Rate Between 1872-2019.” Inflation Calculator, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1872?amount=6000000.

[44] “The Sabbath of the Steed,” The New York Herald, November 4, 1872, p. 9.