Shirley Chisholm’s Brooklyn: Building a Multiracial Coalition in a Divisive Time

By Jason Sokol

Hillary Clinton is not the first woman to attempt to shatter the highest glass ceiling. Perhaps her ascent will establish for some of her forerunners a more prominent place in American political history. Ellen Fitzpatrick’s recent book, The Highest Glass Ceiling, focuses on three such forerunners: Victoria Woodhull, Margaret Chase Smith, and Shirley Chisholm. Chisholm ran for president in 1972, not only a pioneering female candidate, but also the first African American to mount a full-fledged national campaign for the presidency.

Shirley Chisholm and Hillary Clinton both got their starts in electoral politics in New York. And the kind of multiracial coalition that propelled Clinton to the Democratic presidential nomination -– comprised of African Americans, Latinos, and white women –- resembled the one that Chisholm stitched together when she first ran for a seat in the U.S. Congress. Chisholm’s 1968 congressional campaign showed her strengths as a multiracial coalition-builder. In a time of Black Power, urban riots, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville crisis, and deep generational and political divides across the nation, Chisholm showed the viability of a multiracial politics. She built that coalition through a mix of organizational politics and grass-roots campaigning. She displayed an intimate understanding of Brooklyn’s Democratic clubhouses. At the same time, she canvassed block-to-block throughout New York’s newly redrawn 12th congressional district. In that endeavor, her Brooklyn identity became as important as her identity as a woman or as an African American. She tapped into the deep sense of place that many Brooklyn voters prized.

Chisholm was born in Brooklyn, moved to Barbados and attended elementary school there, then returned to Brooklyn at the age of nine. She graduated from Brooklyn College, and ultimately settled in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Chisholm was a fitting symbol of this unique neighborhood, comprised of immigrants from the Caribbean, native New Yorkers, and black migrants from the South. Chisholm pursued her political education in Brooklyn’s Democratic clubhouses. Through the late 1940s and early 1950s, she alternately challenged the leadership in the 17th Assembly District and tried to gain a foothold in the local Democratic Party. She eventually joined two organizations that supported black candidates: the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League in 1953, then the Unity Democratic Club (UDC) in 1960. She knew what it was like to navigate multiple worlds –- with the triple consciousness of being black, female, and American to boot. Chisholm’s background had prepared her to become the consummate outsider-insider.

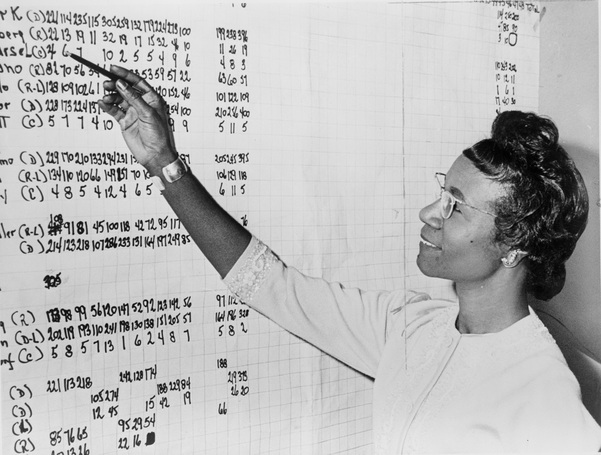

Reviewing political statistics in 1965. Roger Higgins, Library of Congress, New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection.

Chisholm worked in the trenches of Brooklyn politics, until a window opened in 1964. That was when a vacancy appeared on the civil court. Stanley Steingut, head of Brooklyn’s Democratic machine, wished to appease the borough’s growing number of black voters. So he appointed to the judgeship Thomas Jones, head of the UDC and a state assemblyman at the time. Jones left the assembly, and Chisholm won the election for his seat.

Because the district lines were in flux, Chisholm had to run for the assembly again in 1965 and 1966 –- and she triumphed each time.

At the level of congressional districts, Bedford-Stuyvesant was completely gerrymandered. In 1961, the New York state legislature had enacted a law that broke the sprawling neighborhood into so many jagged fragments. The 10th Congressional District, represented by Emmanuel Celler, took in a slice of Bedford-Stuyvesant along with East Flatbush, Park Slope, and Brownsville. John Rooney’s 14th district wound along the waterfront neighborhoods of Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Brooklyn Heights, Red Hook, and Bay Ridge. It also included a sliver of Bedford-Stuyvesant. Edna Kelly’s 12th district encompassed Crown Heights, Flatbush, and Kensington, and swooped through the heart of Bedford-Stuyvesant. The 15th district, represented by Hugh Carey, began near the Brooklyn Navy Yard and snaked slightly inland for some twelve miles -– all the way to the Verrazano Bridge. These four white politicians -– Celler, Rooney, Kelly, and Carey –- represented Bedford-Stuyvesant in the U.S. Congress. Although Brooklyn possessed one of America’s largest black areas, all of the borough’s congressional districts held white majorities.

This began to change under the weight of federal legislation and a series of court rulings. In June 1966, a black activist and journalist named Andrew Cooper filed a lawsuit against New York’s political leaders. He described how Bedford-Stuyvesant’s African Americans had been partitioned “in so tortuous, artificial and labyrinthine a manner” as to strip them of political power. In 1967, a Federal Statutory Court directed the New York state legislature to redraw Brooklyn’s congressional districts.

The new 12th Congressional District would envelop all of Bedford-Stuyvesant. But not only that. It also included much of Bushwick and parts of Crown Heights, Williamsburg, and Greenpoint. African American residents were at its heart and in its majority. Yet they alone would not determine the identity of the new congressperson. The successful politician would have to win over blacks in Bedford-Stuyvesant -– who were themselves a diverse lot in terms of origin and culture -– as well as the Italians of Bushwick, the Jews of Crown Heights, the Polish Catholics of Greenpoint, and the Hasidim and Puerto Ricans who were concentrated in Williamsburg. Shirley Chisholm would later be portrayed primarily as a black politician who enlisted in the black struggle, and as a woman who championed women’s causes. Indeed, she would portray herself this way. But the key to her electoral success lay elsewhere. In the beginning, she built multiracial alliances and spoke many languages -– both literally and metaphorically.

In February 1968, the New York state legislature announced the shape of the new districts. In John Rooney’s Greenpoint district, local politicians and white voters were enraged. They sketched doomsday scenarios in which they would be ripped from their “natural” political home and moved forcibly into an African American district. In their fearful visions, Greenpoint would be subordinated to Bedford-Stuyvesant, the working and middle classes to the destitute, the upstanding to the criminal, and the needs of a majority-white community would be subsumed by those of the black ghetto.

The new 12th Congressional District also welcomed the Italian majority in Bushwick along with a heavily-Jewish piece of Crown Heights. Judith Berek, a Crown Heights resident, actually appreciated the integrated character of the new congressional district. The legislature’s “objectives were not to make a black district, but a fair district… I think it’s very good that the district doesn’t end on Eastern Parkway. It comes over into an area which is probably predominantly white, although I would say completely integrated.” She believed the legislature had succeeded.

While Berek lauded the new district’s multiracial character, and while Greenpoint residents feared this composition, many observers had not even recognized that such a racial mix existed. They still asserted that the new district would be a black district, devoted to black interests. Shirley Chisholm herself declared that the legislators “created a district which would now ensure the election of a black person to Congress.”

There was nothing inevitable about such a result. On March 5, 1968, a group that had joined in the original lawsuit over gerrymandering now updated its complaint. Paul Kerrigan, a reformer and co-plaintiff, sounded a note of alarm. For all of the griping in Greenpoint, the legislature might not have created a black district after all. It only “appeared to create a black district in the new 12th CD,” Kerrigan noted. That appearance could deceive:

By including heavily white areas in Bushwick and Crown Heights, the Legislature created a district in which the ethnic ratio of registered voters -– as opposed to gross population –- is about 50-50. The apparent attainment of long-awaited representation for the people of Bedford-Stuyvesant can turn out to be a vicious delusion.

The neighborhood's boundaries according to the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corp.'s 1968 annual report.

Kerrigan charged that the legislature had actually strengthened the position of white incumbents. It had increased the percentage of white voters in John Rooney’s 14th district. It took several of the black and Puerto Rican areas from Williamsburg and Greenpoint, and pushed them into the 12th Congressional District. At the same time, the 12th district included enough whites from Bushwick and Crown Heights to dilute the votes of those racial minorities. “The new districts… are still clearly drawn to benefit the clubhouse politicians. They are designed to curb Reform movements and to keep Negro and Puerto Rican representation to a minimum.” According to Kerrigan, the legislature had created the impression of empowering racial minorities just as it bolstered the re-election prospects of many white incumbents.

Leaders of the Pioneer Democratic Club considered running an Italian American candidate in the primary. They believed that several African American candidates might split the black vote, and that Bushwick and Greenpoint housed enough Italians to elect the Pioneer candidate. For the same reason that Italian American politicians saw opportunity in the new district, Felix Cosme was moved to outrage. Cosme, a Puerto Rican and a candidate for the state senate, argued that Williamsburg’s Puerto Rican population had been split down the middle. Puerto Ricans would have clout neither in the new 12th district nor in the 14th.

The New York Times overstated the power of white voters, but only by a little. “Although the white population makes up only half the district,” reporter Martin Tolchin explained, “they vote in much greater numbers than the Negroes.” In reality, white residents constituted about one-third of the population in the 12th Congressional District. Blacks accounted for slightly less than 60 percent of the population, and Puerto Ricans for almost 10 percent. But Tolchin was right about the fact that whites registered -– and voted –- in much higher numbers. Among registered voters, whites made up at least 45 percent of the district.

Steingut

Stanley Steingut knew all of this. He was aware that the right white candidate might have been able to win the Democratic primary. But Steingut was not opposed to an African American congressman in the 12th district. This could make Bedford-Stuyvesant, and its black voters, loyal parts of the Brooklyn Democratic machine. Heeding Steingut’s wishes, the Democratic clubhouses put forth no white nominees. Furthermore, the Kings County Democratic organization decided not to formally back any particular candidate.

So was born a “black district,” containing one of America’s largest black areas, primed to send an African American to Congress, in which nearly half of the registered voters were white.

In the Democratic primary, Chisholm ran against State Senator William C. Thompson. Thompson gained the tacit backing of Steingut and the Democratic machine, so Chisholm presented herself as the candidate of the people. It was a brilliant bit of political marketing. She alone, as her campaign pins would declare and as her volunteers would blare through so many megaphones, stood “Unbought and Unbossed.”

The “unbossed” part of Chisholm’s slogan contained an obvious double meaning. She was a strong woman who portrayed herself as apart from the political machine. Chisholm fashioned herself as the candidate for change and reform. Her slogan had the potential to cut across racial and geographic lines. It could appeal to any individual who felt that the men in power had overlooked his or her interests. It might resonate as deeply with a young black mother in Bedford-Stuyvesant as an elderly Jew in Crown Heights. She ran a populist campaign devoted to door-knocking, leafleting, and street-corner organizing.

In effect, two Democratic primaries would take place: one in the majority-black neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, and the other in the four neighborhoods that had large numbers of white voters. The new congressional district held 73,000 registered Democrats. Among the white voters, roughly 16,000 were concentrated in Bushwick, with another 17,000 scattered through Greenpoint, Williamsburg, and Crown Heights. Each candidate had to develop one message that would play in Bedford-Stuyvesant, and another to win over neighborhoods with more white voters. Yet the two messages had to cohere.

Chisholm relied on the deft strategies of Wesley “Mac” Holder. Chisholm and Holder had originally worked together in the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League, had then split apart, and later resolved their differences. In 1968, Holder signed on as Chisholm’s campaign chief. A statistician by trade, Holder calculated that in the 12th district women outnumbered men on the voting rolls by about 2.5-to-1. The difference was 3-to-1 in Bedford-Stuyvesant. This gave Chisholm all the more reason to concentrate on black women. As their assemblywoman, she was already their champion. As the first black woman in Congress, she could become their hero. “The women are fierce about Shirley,” remarked her husband, Conrad Chisholm. “She can pick up the phone and call 200 women and they’ll be here in an hour.” The black women of Bedford-Stuyvesant formed the heart and soul of her campaign.

Still, Chisholm could not find her way to Washington without making inroads in Bushwick. Black voters were likely to split their votes between Chisholm and Thompson, with whites holding the balance of power. She reached out to women’s organizations in Bushwick, and installed herself in the neighborhood for several days. “I have to go into the three big housing projects in that area and take my story to the women in those buildings.” She contended that Thompson and Steingut were playing the gender card. The Amsterdam News referred to this as “‘male image’ propaganda.” And some male voters were responding. “Although I did not want to interject the sex angle in the campaign, I was forced to bring it into the open. Because the undercurrent of, ‘we don’t want a woman, we don’t want a woman,’ was really beginning to get in my way.” Chisholm pursued a three-pronged strategy in Bushwick: she made a pitch to the women, against sexism; she touted her own political independence, in contrast to the Democratic machine; and she focused on grass-roots organizing.

In neighborhoods accustomed to supporting white men, Shirley Chisholm cut a striking figure. “You are going to have a black representative,” she told the voters. But “if you want a representative who truly represents your hopes… in terms of principles, et cetera, there is not one who can match me.” To the women especially, Chisholm stressed that they all stood on a historic threshold. “I told them I was about to make history in this country.” Chisholm infused it all with a street-wise populism. “I went out on the trucks, told the people we could all be liberated from the machine.” This formed the essence of Chisholm’s appeal.

If there had been both a white primary and a black primary in the 12th Congressional District, they would not have sufficed. For Puerto Ricans made up half of Williamsburg’s population and a significant part of Bedford-Stuyvesant’s. Chisholm held a decided advantage among those voters. In the Puerto Rican neighborhoods, she conducted much of her campaign in Spanish. “None of my opponents have ever been able to do this, and so this in itself is a common bond between myself and the Puerto Rican people.” Puerto Rican voters warmed instantly to her.

On Primary Day, June 18, Chisholm captured 46 percent of the votes compared to 39 percent for William Thompson. Chisholm eked out victories in Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and Crown Heights. She carried Bedford-Stuyvesant more convincingly. Thompson carried Bushwick, but by only fifty votes.

The campaign barely finished, a certain narrative about Chisholm’s victory began to take hold. She helped to author that story. “From the beginning of this campaign,” she said in her victory speech, “I was aware of the barriers, hidden and otherwise, that stood in my path.” She drew her strength from African Americans in Bedford-Stuyvesant. “The reason for continuing in the race was the faith that the people of Bedford-Stuyvesant had in me.” The media -- local and national, black and white –- spun the same tale. Here the black people, long oppressed and finally empowered, had selected a black woman to lead them. The Amsterdam News declared that Chisholm showed “her extraordinary ability to sweep up the black and the Puerto Rican vote.” If white voters had proved crucial during the primary campaign, they became tangential to the victory narrative. The story was that Bedford-Stuyvesant had picked Chisholm up on its broad shoulders and carried her ever closer to Capitol Hill.

Farmer

In the general election, she faced James Farmer –- the well-known civil rights leader. Farmer posed as the strong black male, and tried to portray Chisholm as the fragile woman. His flyers emphasized the need for a “strong male image” and a “man’s voice” in Washington.

Farmer also inserted himself in the arc of the rising Black Power movement. From the back seat of a convertible that whisked him through the district, he often clenched his fist in a Black Power salute. When Farmer walked the streets of Bedford-Stuyvesant, he brought along a group of men who sported Afros and beat bongo drums. Across the nation, Black Power advocates were encouraging African Americans to celebrate their African roots and to bask in the beauty of their blackness. They urged black men -– who white Americans had long pressed into straitjackets of deference –- to embrace their masculinity and to seize their manhood.

The New York Times reinforced Farmer’s description of this as a man-versus-woman struggle. It placed Farmer at the center of the story with Chisholm on the periphery. An October article was headlined, “Farmer and Woman in Lively Bedford-Stuyvesant Race.” This nudged Chisholm further toward a gendered pitch for votes. She explained, “It was not my original strategy to organize womanpower to elect me… But when someone tries to use my sex against me, I delight in being able to turn the tables on him.”

Chisholm told the women of the 12th Congressional District to make good on their numerical advantage. “You’ve got to elect one of your own to dramatize the problems that are focusing on us as black women.” She always insisted that she had been forced to play up the gender issue. “I hate to do this, but the men are carrying on in this campaign. So they forced me into this position.” This claim contained strands of truth as well as pieces of political strategy. On the one hand, Farmer really did make political hay out of Chisholm’s sex. On the other, Chisholm and Mac Holder had long realized that women outnumbered men on the voter rolls -– and that in this statistical fact existed a potential political treasure.

Whether a defensive maneuver or an attack, this line of campaigning proved potent. Marshall Dubin, an organizer for Local 1199, noted that the union contained a majority of women. Many worked as nurses and orderlies and even janitors, hundreds of them in the Downstate Medical Center. In Bedford-Stuyvesant, often “the woman’s the sole supporter for the family. And I tell you this is very common in the hospital.” In Shirley Chisholm these working women saw themselves. Yet they also saw a leader who climbed to heights that they would never contemplate. Dubin looked at the women in his union and observed how Chisholm had inspired them –- how she had drawn them into electoral politics, a realm heretofore meaningless to so many. “She has captured the imagination of our people… people in Bedford-Stuyvesant, working people… Women do identify with her.” Chisholm “was born and raised in the midst of this mess,” managing “to come up out of the bottom, and make something of herself, and still relate to them. And that means something.” Dubin observed that those who criticized Chisholm had leveled only one main charge. They maintained, “you really can’t have a woman in a job like this.” It was a sexist claim, and it overlooked an obvious fact: the current representative, Edna Kelly, was also a woman. “To then object to a black woman doing this, who is of the people… is I think the height of unfairness.”

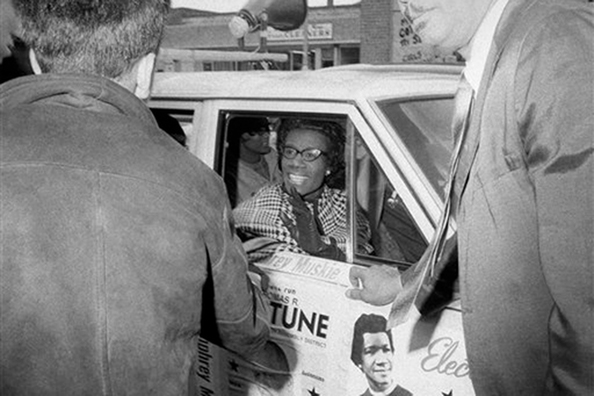

Chisholm crafted a message that men could also rally around. On October 29, 1968, she brought her campaign to one of the newer housing projects in the area. These were the Ebbets Field Apartments, a 1,300-unit complex that started accepting tenants in 1963. It stood on hallowed ground. “You know I have worked in the legislature. You know what I have stood for. You know I’m unbought and unbossed.” At large rallies, the candidate often used such generalities. Other volunteers picked up the megaphone to communicate the details of her platform: “Adequate pay for the thousands of unemployed, quality education in all the schools, adequate housing for both low and middle-income families, better support for daycare centers, unemployment insurance for the domestic workers.” Chisholm continued, “Vote for a congressman that belongs to this community.” And she attacked James Farmer. “Send me to be your voice. Do not let anybody from Manhattan, or any place else, come over here and be an opportunist and try to be your voice.” Voters appreciated her Brooklyn roots. A man of Jamaican descent predicted victory for Chisholm. “I think Chisholm will win – based on the fact of her popularity and the work she has done in the community.”

Chisholm canvassing at the Ebbets Field Apartments in 1968.

Her Brooklyn roots were as important as her bond with black women. Farmer was an outsider; Chisholm was an authentic Brooklynite.

Chisholm ultimately crushed Farmer on election night. She won two-thirds of the total votes to Farmer’s 26 percent. The national media focused upon the fact that Chisholm had become the first black congresswoman. In an evening, Shirley Chisholm had become an icon.

Many of her constituents emphasized Chisholm’s Brooklyn identity more than her womanhood. As one volunteer said on Election Night, Chisholm “played in these streets and knows what we need.” The precise place of her triumph – the heart of black Brooklyn, an area of meat pies and soul food, graceful old brownstones that stood alongside the travesties of the slumlords, crime-besotted corners and rat-filled groceries, the racial smorgasbord that was Crown Heights, the Old-World fabric of Greenpoint, the Williamsburg where Hasidic Jews shared the avenues with migrants from San Juan, the housing complex that inherited the legacy of Jackie Robinson’s mad dashes, and all the places in between – remained meaningful to those who had elected her. “It’s also significant that people are sending one of their own,” reflected Judith Berek. “Not just because she’s black and most of them are black. But because she lives there. And I imagine it would be a really kind of spectacular feeling to send your next-door neighbor to Congress. Just in terms of, if your next-door neighbor can go, you can go too.” If the women of Bedford-Stuyvesant could send Chisholm to Congress, “maybe the great Horatio Alger really works. You really can go from being a neighborhood schoolteacher to being a Congresswoman. The kind of thing where when your mother hits you over the head to do your homework and say… you can go to Congress like Shirley Chisholm, it really happens.” Suddenly, Bedford-Stuyvesant possessed hundreds of future Shirley Chisholms.

The story of Chisholm’s election held within it an irony. In order to win the Democratic primary, she had to reach above and beyond her base of African American voters in Bedford-Stuyvesant. She built that multiracial coalition in a divisive time.

In many ways, Clinton confronts a similar challenge. In our current moment, racial hatred has burst into the open. Police killings of black men will not abate. The Republican presidential nominee proposes to formally divide the country along lines of race and ethnicity -– vowing to build a wall on the southern border and to discriminate against refugees on the basis of their religion. At a time of such tension and enmity, Clinton’s political fortunes depend upon her own ability to at once compel and unite different segments of the electorate: black, brown, and white.

Jason Sokol is an Associate Professor of History at the University of New Hampshire. This post is adapted from All Eyes Are Upon Us: Race and Politics from Boston to Brooklyn (Basic Books, 2014).