Schlep in the City: Forest Hills

By Frampton Tolbert

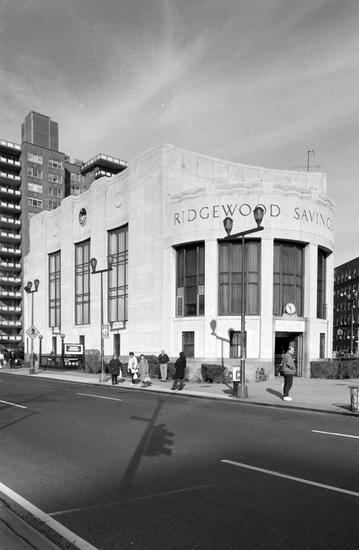

Ridgewood Savings Bank, 1995. Photo by Edmund Vincent Gillon. Museum of the City of New York.

Queens is a borough of enclaves, each distinct. While the borough was formed in 1897, development did not begin in earnest until the 1920s, when the population doubled to more than one million people.[1] For this increase in population, buildings were needed for people to live, work, go to school, and worship—and some of which were defining examples of early modern design. While people may think it was Manhattan where this architecture was focused, Queens definitely exemplifies this as well. There was rarely a concentration of new architecture in a single neighborhood and more often, neighborhoods had one or two examples sited among older structures. But one neighborhood that has a cohesive group of significant modern architecture is Forest Hills.

Forest Hills was named for Forest Park on its South Side. However the more bustling area of the community runs along Queens Boulevard and the neighboring commercial Austin Street. In 1930, in anticipation of growth due to the building of the Queens Boulevard subway line, several blocks of land along Queens Boulevard were rezoned so that fifteen-story apartment buildings could be built. Developer Cord Meyer had a head start, having bought 600 acres in the area in 1906. Meyer's first apartment building was constructed in 1917 with additional ones completed in the 1920s.[2]The opening of the Independent subway line with a stop at Queens Boulevard and Continental Avenue in 1936 was another major improvement which stimulated growth in the area, reflected in new businesses opening here. We begin our tour at one of these businesses from the late 1930s.

The Forest Hills Branch of the Ridgewood Savings Bank from 1939-40 is the neighborhood’s only designated New York City landmark. The architects Halsey, McCormack & Helmer, were known for bank architecture, designing all over the city, including the home office of this bank (in Ridgewood), and the Williamsburgh and Dime Savings Banks in downtown Brooklyn.[3] The bank managers chose the Forest Hills location for the bank's first branch office because of its growing population and newly-opened subway stop. The style is Deco, not Modern, with alternating flat limestone surfaces with incised designs and large expanses of windows. It was definitely a statement building when it opened.

Behind the bank on 71st Avenue are two modest, yet engaging buildings. First, the Forest Hills Library, is a moderne design from 1957. It was designed by Boak & Raad and was one one of several new libraries built in New York at the end of the 1950s. Boak and Raad were known as prolific apartment building designers in Manhattan. We can see here such details as the concrete window surrounds, metal entrance canopy and flagpole, and the angularity of the structure as a whole.

Forest Hills Library. Photo by author.

Next door to this is the St. Regis, typical of the ubiquitous red brick apartment buildings that went up in Forest Hills and Rego Park starting in the 1930s. This one is from the 1960s and was designed by the prolific Philip Birnbaum. Birnbaum got his start in the neighborhood working for developer Alfred Kaskel. He was both admired and reviled for specializing in stripped down and efficient designs. According to The New York Times,“‘banal' was among the kinder words used to describe his work.”[4] But he was indeed prolific, designing more than 300 buildings across the city and credited as among the first to incorporate rooftop pools, terraces on both sides of the apartments for cross breezes, and exterior access which eliminated the need for interior public corridors.

While not so noteworthy on the outside, the St. Regis was marketed with the latest amenities, including air conditioning, private terraces, linoleum floors, and sound resistant walls[5]. While these features may seem common today, they were desirable options for residents, many of whom were probably first time homeowners moving from other parts of the city. Developers were trying to differentiate themselves from all the other buildings going up right around them in Queens neighborhoods like Forest Hills.

Walk back to Queens Boulevard and cross to MacDonald Park, created in 1933 and named for Captain Gerald MacDonald, a Forest Hills resident who served in World War I. Captain MacDonald’s brother, Henry MacDonald, Forest Hills resident spearheaded the effort to name the park in honor of MacDonald. A statue of him was unveiled in 1934, sculpted by Frederic de Henwood, who was also Henry MacDonald’s brother-in-law.[6]

Abutting MacDonald Park are two significant modern structures.

Forest Hills Jewish Center. Photo by author.

First is the Forest Hills Jewish Center by Joseph Furman. Furman’s firm was founded in 1923 and he did work in Deco, Craftsman, Neo-Renaissance working on more than two dozen projects in Manhattan alone. Why did Furman design this synagogue? For one thing, Furman knew the Rabbi, in fact the Rabbi performed the marriage of his son architect Lawrence Furman, and the bar mitzvah of his grandson Rich Furman.[7] This follows the trend of architects of mid-century synagogues having existing connections to the congregations, compared to congregations like Catholic churches where the diocese used a few select architects for all projects.

The complex dates from 1949, just a few years after WWII, when construction was just returning to normal. The congregation was created from among the thousands of Jewish families moving to Forest Hills at this time. The exterior is of crab orchard stone and brick—the stone was first used in the 1920s but became very popular in the mid century—it is very durable and weather resistant. The interior is quite restrained with a focal point of the Holy Ark by Arthur Szyk, a renowned Polish-born illustrator. This is one of his few 3-D designs and only known one for a synagogue. Unfortunately this complex, including the extensive school behind is currently proposed to be replaced by a new 10 story building with space for the congregation within it.[8]

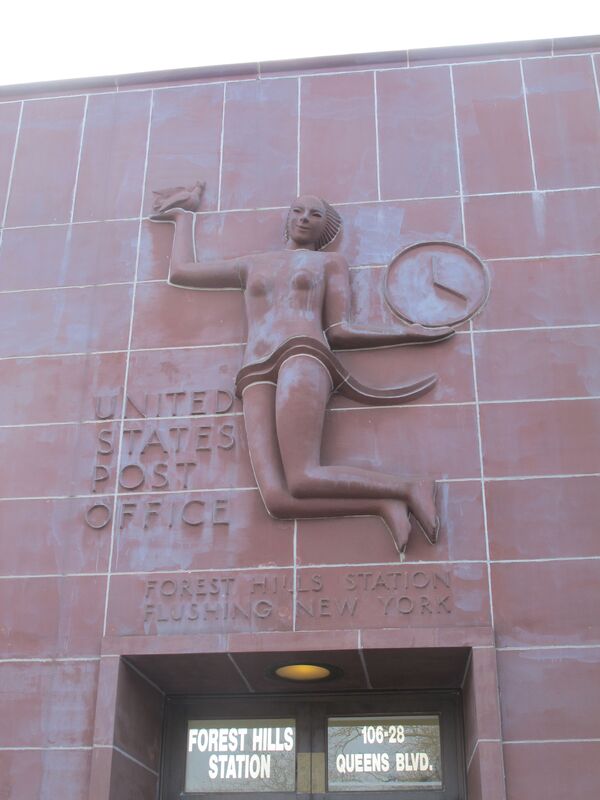

One of the earlier modern buildings is the Forest Hills Post Office from 1937. It was a part of the Works Progress Administration initiative to build post offices across the country. And what is perhaps most striking is the design, as evidenced by this quote from architectural historian Andrew Dolkart of Columbia University School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, who has said that the “Forest Hills Station is a simple, Modern design. It is basically two cubes that have collided…It is a mystery…just how the government chose to fund this project, at a time when most post offices were Colonial Revival.”[9]

The design is unusual for NYC and consists of terra cotta cladding by the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company of Staten Island.[10]There are at least three more intact terra cotta-clad post offices in the New York area, but still a rarity. The only ornament on the building appears in the lettering spelling out “United States Post Office, Forest Hills Station, Flushing, New York.” The large terra cotta relief sculpture, “the Spirit of Communication,” was created by sculptor Sten Jacobson, a Swedish American sculptor. When she was first revealed, local residents protested and complained about the nudity.[11]The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988, but is not a city landmark meaning it could still be demolished.

Lorimer Rich was the architect—a graduate of Syracuse University and former employee of McKim, Mead & White. In 1928, he left that firm and opened up his own office in Washington DC. He became one of the many architects designing post offices and other government buildings for the Architect of the Treasury.

Cord Meyer Building. Photo by the author.

At 108-18 Queens Boulevard is a building that represents the other end of the Modern era. One of the last truly modern buildings constructed in Queens, the Cord Meyer Office Building of 1969 by Liebman-Liebman and Associates. The structure includes nine stories, with a masonry core on one end and the rest as aluminum and glass curtain wall. There is also a lobby of bronze panels and white marble. By the time it was built, this Miesian, Park Avenue modernism was a bit out of date.

Next door is the Midway Theatre, named for the Battle of Midway, which took place in 1942, the same year the theater opened. It was designed by the prolific theater architect S. Charles Lee for Thomas W. Lamb Associates, the eponymous architectural firm headed by the even more renowned theater architect.[12]While most theaters credited to Lamb are in a variety of revival styles from solid Colonial Revival to the fanciful and exotic Moorish Revival, Lee was an early adopter of more modern styles including the Midway’s main style, Moderne.[13]The streamlined facade with strong vertical elements exemplifies this and is also a nice counterpoint to the deco designs of the earlier Ridgewood Savings Bank nearby.

To finish our schlep, head back to 71st Street and walk along, crossing Austin Street, the main commercial corridor, and under the Long Island Railroad overpass. You’ll end up at the corner of 71st Street and Burns Street. Directly in front of you will be the Forest Hills Gardens entrance portico.

Forest Hills Gardens is not modern in style, but groundbreaking in its role as one of the first garden city developments in the United States. The garden city movement began in the United Kingdom and in 1909 it arrived in Queens. The force behind Forest Hills Gardens was the Russell Sage Foundation which hired architect Grosvenor Atterbury and the preeminent landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to design the Gardens.

While the Gardens themselves are overwhelmingly significant, we will look at the final building that was constructed in the community to complete our Forest Hills Modern tour. When walking through the Gardens remember this is still a private community that is regulated internally. You cannot park in the Gardens without a parking pass.

Leslie Apartments. Photo by author.

At 159 Greenway Terrace is the Leslie Apartments, a large complex that brings together modern fire safety with the strict old world design of this private community. The building is surrounded by a decorative wall with an arched brickwork entrance; there are no fire escapes but two forms of egress, and an underground parking garage. The building occupies a large triangular plot located not far from the main entrance to the Gardens and was the last building to be constructed, rising on the site of the Russell Sage Foundation’s sales office in 1948. Fellheimer and Wagner, a firm known for both train stations but also some surprisingly modern designs were the architects.

Here at the Leslie Apartments seems a good place to end our schlep, a place that speaks to an interesting marriage of modern convenience with historical design. In conclusion, all of the buildings featured in this schlep help demonstrate that New York City’s modern heritage is not defined by the major, world-renowned projects found largely in Manhattan but by the hidden gems found in regular neighborhoods created by regular architects. These architects took modernist principles and used them to transform Queens neighborhoods like Forest Hills, which were experiencing tremendous growth in the mid-century, helping create the neighborhoods we know and appreciate today.

Frampton Tolbert is an architectural historian focusing on the study and documentation of vernacular and regional modernism. He created the digital projects Mid-Century Mundane and Queens Modern to explore the rich history of modernism in Queens and beyond.

Notes

[1]“Population of New York State by County: 1790-1990,” New York State Department of Economic Development, State Data Center, accessed April 15, 2019.

[2]“Ridgewood Savings Bank, Forest Hills Branch” Designation Report, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, May 30, 2000.

[3]Ibid.

[4]“Philip Birnbaum, 89, Builder Celebrated for His Efficiency,” David W. Dunlap, The New York Times, November 28, 1996.

[5]“St Regis...the Crown Jewel of Forest Hills,” New York Real Estate Brochures Collection, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, undated.

[6]“MacDonald Park,” New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, accessed April 3, 2019.

[7]Rich Furman, in interview with the author, April 18, 2017.

[8]“Forest Hills Jewish Center to Redevelop its Site, 10-story Building that will include Synagogue to Replace it,” Tara Law, Forest Hills Post, January 17, 2018.

[9]“Forest Hills Station Post Office - Forest Hills, NY,” The Living New Deal, accessed March 20, 2019.

[10]“Forest Hills Station,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, accessed March 20, 2019.

[11]Ibid.

[12]“RKO Midway Theatre,” Forest Hills & Forest Close, Queens brochure, Historic District Council, accessed April 1, 2019.

[13]“S. Charles Lee (1899-1990),” A Guide to Historic Architecture in Fresco, California, accessed April 1, 2019.