Two-Hundred Fifty Years Of Organ-Building In the City: PART I — 18th-Century Imports and a Burgeoning 19th-Century Cottage Industry

By Bynum Petty

With the deaths of J.S. Bach in 1750, Georg Frideric Handel in 1759, and Georg Philipp Telemann in 1767, the culmination of northern European organ-building was in its waning years. The glorious era of the French Romantic organ was in the queue but would not blossom for another hundred years, while the English were still hopelessly mired in intransigent parochial tradition. Meanwhile the British and Dutch colonies in America were growing, and the diverse range of migrants populating North America were eager to bring their respective cultural heritages in tow, including the pipe organ.

Henry Erben organ, 1868. Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral. Mulberry Street.

After the Declaration of Independence was adopted by delegates to the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, there was little written about the concurrent history of the pipe organ in North America for more than a hundred years. Not until the publication of Everett E. Truette’s The Organ: A Monthly Journal Devoted to the King of Instruments (1892) was little published attention given to the pipe organ in the United States. About a decade later, the Scottish architect and New Yorker George Ashdown Audsley published in two volumes his encyclopedic The Art of Organ-Building in 1905. While universal in scope, a significant portion of the monograph is devoted to the development of organ-building in the United States.

As important as they are, these late-nineteenth and early twentieth century studies are diminished when compared in quantity and quality to those following the end of World War II and especially those following the founding of the Organ Historical Society in 1961. [1] From the ‘70s onward, monographs and essays on American pipe organs have burgeoned beyond expectation lead by the intrepid work of Barbara Owen. Today there is no dearth of published American organ-building history, but it’s far from complete with much more to be discovered.

Among the first European organ-builders to establish a workshop in the colonies was Johann Gottlob Klemm (a.k.a. John Clemm, 1690 – 1762.) He apprenticed organ-building with the Saxonian master Gottfried Silbermann — a colleague of J.S. Bach — and upon his 1733 arrival in Philadelphia, became one of America’s first professional organ-builders. Word of Klemm’s skills spread rapidly to New York City. Trinity Church, Broadway at Wall Street, was established in 1697, and a year later constructed its first building. The church building was enlarged in 1735 and again in 1737. In 1738, the Vestry voted to solicit organ proposals, and on June 1, 1739, they approved Klemm’s bid to build an organ for Trinity Church. [2] The instrument was large by contemporary standards and turned out to be beyond Klemm’s ability, as it was significantly larger than any other organ to come out of his workshop. Facing insurmountable mechanical defects, the Vestry voted to sell the organ in 1762, and identified it as “large, consisting of 26 stops, 10, in the Great Organ, 10 in the Choir Organ and 6 in the Swell. [3] It may be inspected; will be sold cheap, and the purchaser may remove immediately.” [4]

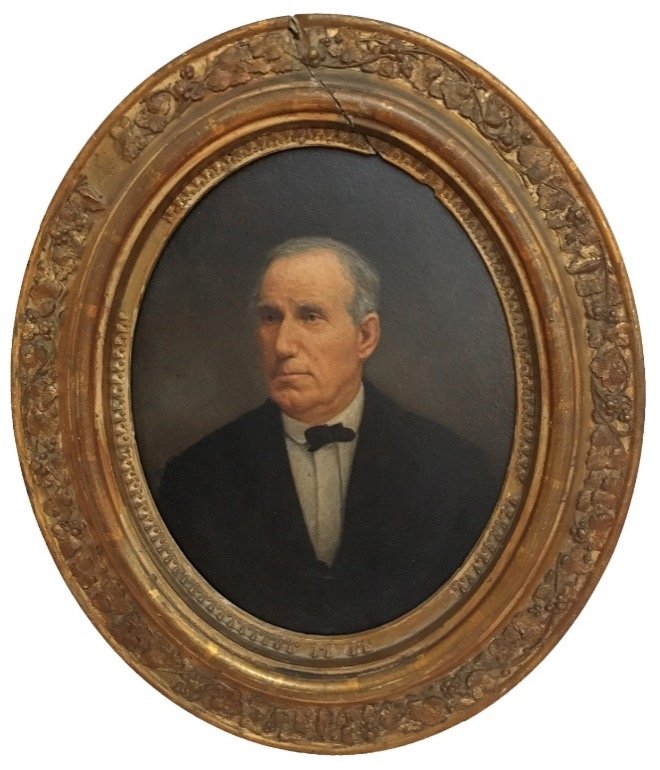

Henry Erben, c. 1840. Courtesy Charles Gosse.

Klemm’s organ was replaced by a small instrument designed by John Snetzler in 1764, a highly respected London organ-builder; but the imported organ had a short life as it was burned in the great New York fire of 1776 that destroyed a significant portion of the City as the Americans abandoned it to the British during the opening of the American Revolution. Thus, the history of organs in Manhattan’s most prominent church — and all others actually — would stumble along in fits and starts for another seventy years until the genius of Henry Erben asserted itself.

And assertive it was. Who was Henry Erben? Here in full is a transcript of Erben at his most repugnant [and colorful] disposition:

I encountered a very queer old fellow the other day, Henry Erben, the champion church-organ builder of the United States, some seventy-five years of age, perhaps more, for he made organs here in 1824 – fifty-five years ago. He is a large aggressive, rather rude and brusque in bearing, and animosities stick out all around “like quills on the fretful porcupine.” He always carries with him a heavy staff, with which he pounds on the floor to punctuate his conversation. And they do say that his name is not a variation of “urbane.”

“Mr. Erben,” I said, “you have made a good many organs in your time?”

“I have made more church-organs,” he said, “than any other house in this country or the world. No other establishment has turned out so many as ours.”

How many have you built? Hundreds, no doubt.”

“Hundreds? Thousands. Why we have built more than two hundred church organs for New York City alone. Here is our pamphlet in which record is made of more than one thousand in this country.”

“What churches are your principal patrons?

“O, Episcopal and Catholics, of course. You know I never build an organ for Jews and Unitarians.”

“Is it possible? What sort of freak is that?”

“It is no freak at all,” he exclaimed, pounding on the floor. “I hate Jews and Unitarians. My organs won’t play any music but Christian music.”

“Suppose Jews come to you for an organ — what do you do?”

“I send ‘em right off!” exclaimed he, rapping a lively tattoo on the floor. “I never built an organ for the detested race yet, and I never will. And I never’ll build an organ for the Unitarians, either. They’re just as bad as the Jews — every whit. I never sold but two organs to Unitarian churches in my life, and both the churches burnt down.”

“A couple of fellows came to get an organ a month ago. I suspected ‘em. They talked through their noses, and they wouldn’t look me straight in the eye. And then I knew well enough they were from Massachusetts folks. I hate Yankees. I have refused to sell organs to Massachusetts, Vermont, and Rhode Island for the last twenty years.”

“Did those two men get the organ?” I hinted.

“Get it!” he exclaimed, pounding on the floor. “Not Much! I knew they were from Massachusetts, and I cornered ‘em, and they finally admitted it. And I finally found out they were from Springfield.”

“What denomination?” says I. “Unitarian,” says they. “I don’t make Unitarian organs,” says I: “I only make Christian organs . . . and I sent ‘em off to buy an organ somewhere else.” [6]

Irascible? Yes. Bigoted? Yes. New York’s greatest and most successful organ-builder of the era? Yes.

Hall & Erben (later Henry Erben) organ, 1841 at Market Street Reformed Church (later First Chinese Presbyterian Church). Henry at Market Streets.

In the early nineteenth century, New York City directories list over a dozen organ builders with the work of most limited to tuning and maintenance; but one — Thomas Hall — made significant contributions to organ building in the City. He was born in Philadelphia in 1791, took an apprenticeship and established his business in 1811 in his native city. In 1816 he moved his business to New York City and set up shop in the heart of today’s Chinatown on Mott Street near Bayard with the young Henry Erben as his first apprentice. Hall’s business flourished and Henry Erben proved himself such a valued employee that he became a full partner with the legal name of the firm changed to Hall & Erben in 1824. The partnership was dissolved in 1827, yet oddly enough Thomas Hall remained in the employ of Erben for another sixteen years. One of the earliest Hall & Erben organs known was built in 1824 for Market Street Reformed Church, now First Chinese Presbyterian Church on Market at Henry Streets, the second oldest church building in New York City. Erben rebuilt and enlarged the organ in 1841.

Henry Erben was born in 1800 in New York City, where his father was occasionally identified in city directories as a grocer, and by the time Henry was born, as a musician. He was organist at Christ Church (Ann Street) in 1801 and later at St. George’s Chapel (Trinity Parish). In 1820 he was appointed organist at Trinity Church where he retired. His musical abilities were typical of his era — mediocre at best — especially when compared to the talent of his successor Edward Hodges, appointed organist in 1839, a position he held until 1863. It was during Hodges tenure that Henry Erben built his largest and best-known organ during his long career from his workshop on Centre Street.

Edward Hodges, c. 1836. Courtesy Library and Archives of the Organ Historical Society.

Edward Hodges (1796–1867) earned a Mus. Doc. degree from Sydney Sussex College of Cambridge University. Unable to secure a cathedral job in England, however, he established himself in New York City and is credited for creating a new and lasting order of church music in America. Apart from overseeing the construction of Erben’s organ at Trinity Church, Hodges succeeded in establishing in America his own English cathedral-style music program as the ideal to which many American churches—Anglican and non-Anglican, city cathedral and country parish—would aspire. Hodges was proud of his time at Trinity Church, and said to his daughter late in life, “I used to make a good run there.” [7] More than 150 years after his death, his influence remains widespread.

Hodges’ relationship with Erben was testy at best, in part caused by Peter Erben’s forced retirement and replacement by Hodges, notwithstanding Henry Erben’s notoriously fractious demeanor. Yet the two were compelled to work together on plans for an organ to be planted in Richard Upjohn’s new edifice for Trinity Church at Broadway and Wall Street. The organ was Erben’s largest and at the time the largest in the country. Erben published an 1848 notice while the organ was under construction:

GRAND ORGAN, now building by Henry Erben, to be erected in Trinity Church, in the City of New-York

This Church will be the most splendid Gothic structure in America. The vestry have appropriated $10,000 towards the erection of an Organ, commensurate with the proportion and style of this noble edifice. The design of the Case, which will be constructed of oak, of rich Gothic, is from the drawings and plans of Mr. Richard Upjohn, Architect of the Church. The Organ is building under the superintendence of Dr. Hodges, Musical Director of Trinity Parish. Some idea may be formed of its magnitude from the following: — The organ case will be 53 feet high, 27 feet wide, and 32 feet deep. The largest wooden diapason pipe will be of such dimension, that the interior will measure upwards of 250 cubic feet. Its internal measurement is 36 inches by 30, and 32 feet long. The largest metal diapason pipe, which is seen in the centre of the front of the organ, will be five feet in circumference, and 28 feet in length. There is to be four separate organs, known by the names of Great Organ, Choir Organ, Swell Organ, and Pedal Organ; forty-three draw stops, eleven of which will be diapasons, one of 32 feet in length, and four of 16 feet in length, besides two reed stops of 16 feet in length. The whole number of pipes amounts to 2169. The entire weight of the organ is estimated altogether at upwards of forty tons. [8]

Henry Erben organ, 1848, watercolor of façade. Trinity Church. Broadway at Wall Street. American Architect and Building News, May 23, 1896.

Thus, Henry Erben established himself as the greatest organ builder in the country, and with this instrument set new standards of construction and tonal quality by which all others were judged. Erben’s instruments simultaneously established New York City as the leading center of organ building, which it remained for the next nine decades. During this period of growth and excellence, the organ-building firms of Ferris, Jardine, the Odells, the Robjohns, and the Roosevelts flourished. Their work and contributions to the “King of Instruments” and the organ’s movement into secular spaces will be examined in Part II of this paper. [9]

Bynum Petty is Archivist Emeritus of the Organ Historical Society and recipient of its Magna Cum Laude Award for distinguished service. He has written four books on various aspects of American pipe organ history; the last, M.P. Möller: The Artist of Organs — The Organ of Artists, was released in January 2024. Previously, he was founder and managing director of Petty-Madden Organ Builders, a position he held for thirty years.

[1] The unofficial founding of the Organ Historical Society occurred on June 27, 1956, during the 23rd national convention of the American Guild of Organists in New York City. On May 3, 1961, the organization was incorporated in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, with its headquarters at the York County Historical Society, York, Pennsylvania.

[2] Morgan Dix, A History of the Parish of Trinity Church in the City of New York, vol. 1 (New York; Scribner’s 1898), 198.

[3] A “stop” is a general term denoting different sets of organ pipes. “Great” and “Choir” are names commonly given to the various sections of an organ, each controlled by separate keyboards.

[4] Rita Susswein Gottesman, The Arts and Crafts in New York 1726 – 1776 (New York: The New York Historical Society, 1954), 371.

[5] Ironically, Erben built several organs for both.

[6] “An Old Knickerbocker,” Abilene Gazette 5, no. 52 (December 26, 1879).

[7] Faustina Hasse Hodges, Edward Hodges (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Songs, 1896), 217.

[8] Henry Erben, “1848 List of Organs.” Organ Historical Society Library and Archives, Villanova.

[9] So named by Mozart in a letter to his father, October 17, 1777.