Muhammad Ali in New York, 1967-1970

By Raymond McCaffrey

On a winter day in February 1967, pedestrians gawked as a young African American man walked along Fifth Avenue in New York City: He stood 6 feet, 3 inches tall, aged twenty-five and he was clearly in fighting shape.[1]

“Is that you, Muhammad Ali?’ one woman exclaimed. “You're so handsome."

Ali thanked the passerby and continued to stroll freely alongside Robert Lipsyte, a young sports writer for The New York Times. “Love New York," Ali told Lipsyte. "Always something to do. You can go to any kind of restaurant, always find a movie, or just walk and look at people and traffic; that's fun, too."

A month later, on March 22, 1967, Ali knocked out Zora Folley in a historic fight, the ninth defense of his heavyweight championship and his final at the third Madison Square Garden, soon to be replaced by a new arena atop Penn Station.[2] The fight also proved to be Ali’s last one until October 26, 1970.[3] Soon after the Folley fight, Ali refused to be inducted into the Army, citing religious reasons, and boxing’s governing bodies stripped Ali of his title and barred him from fighting.[4] Though he lived in Chicago for much of this period, New York City became the focal point of Ali’s fight with both the US government and the boxing establishment. With the help of a powerful array of news outlets and personalities, Ali fought his battle in the emerging media capital of the world.

Ali or Clay: Choosing A Name

Mainstream sportswriters had hardly led the way for civil rights advances in sports, largely ignoring Jackie Robinson's historic breaking of the color line, a reaction that African-American journalists labeled a "conspiracy of silence."[5] But the emerging influence of television in the 1960s upended that entrenched power, proving to be the death knell for many newspapers. The New York Herald Tribune, the New York Journal American, the New York World-Telegram & Sun, and the New York Daily Mirror all ceased publication in the mid-1960s, leaving the city with only three daily newspapers — The New York Times, the New York Daily News and the New York Post — by the end of 1967.

For much of Ali’s exile, the allegiance of various media outlets could be gauged by how they identified the fighter. In 1967, the Columbia Journalism Review offered a scorecard: "In Muhammad Ali's corner: Sports Illustrated, Ramparts, and almost every Negro publication in the country. In Cassius Clay's corner: The Associated Press, United Press International; the National Broadcasting Company, The New York Times, and most of the rest of the news media. The Columbia Broadcasting System and Life appear undecided, now going one way, now the other."[6] When queried about The New York Times’ policy, Clifton Daniel, the newspaper’s managing editor, gave CJR a somewhat testy and impolitic comment: “It's a simple matter that the man's name is Cassius Clay. It's his legal name, the name given when he was born. There is no moral feeling about this: if he wants to call himself Jesus Christ, we don't care. It's not a matter of principle but a matter of practice.”[7]

Nonetheless, the newspaper evidently did not impose a strict rule regarding what name staff writers could use. Robert Lipsyte could use the fighter’s Muslim name while his veteran colleague, Pulitzer-Prize winning sports columnist Arthur Daley, called him Cassius Clay. In a column on New Year's Day in 1968, Lipsyte wrote: “Ali’s fate in the white courts may have many repercussions, some subtle and long-range, in a sports world that is increasingly dominated by black stars. Some of them believe that racism directed all the moves against Ali …”[8] Lipsyte also used his column to oppose the boxing establishment’s effort to strip Ali of his title while he was appealing his sentence. When the New York State Athletic Commission sanctioned a fight between Joe Frazier and Buster Mathis at the new Madison Square Garden, Lipsyte objected to the inherent conflict of interest at play with the state’s main boxing promoter profiting with the help of a regulatory agency that subsisted on taxes and licensing fees from the fight industry.[9] Lipsyte wrote that Edwin Dooley, the commission’s chairman, had “committed the first blatant outrage of the infant sports year.”[10]

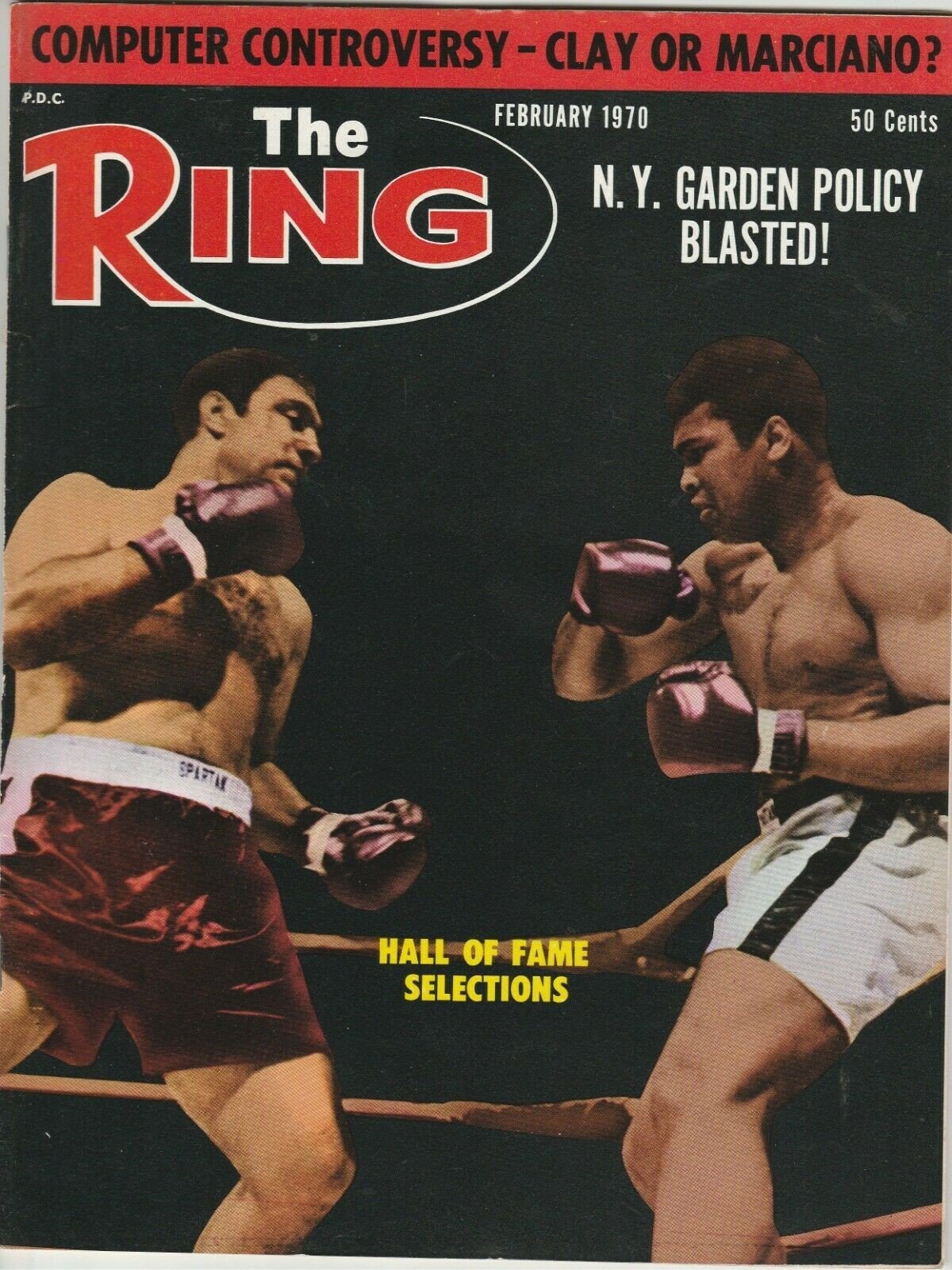

Nat Fleisher and the Ring magazine

Perhaps the single most important journalist during Ali's exile was not at The New York Times but rather the publisher of a niche magazine called The Ring. Nat Fleischer — known as "Mr. Boxing" — had founded The Ring in 1922, and since 1933 the magazine had published a monthly ranking system of boxers that The New York Times described as so “authoritative” that it trumped the rankings of the world's various boxing organizations.[11] Fleisher continued to identify Ali as the heavyweight champion through almost the entirety of his exile.

Fleischer was sports editor of the New York Telegram when he helped found The Ring. Though Fleisher kept the magazine's offices at both the old Garden and then the new arena above Pennsylvania Station, he believed the publication was independent from the industry it covered and ignored the financial interests of his landlord with his continued ranking of Ali as the champion. Fleischer felt it would be unfair to dethrone Ali while he was appealing a five-year prison sentence and a ten-thousand-dollar fine for evading induction.[12] The Ring finally ranked Frazier as heavyweight champion after he beat World Boxing Association title holder Jimmy Ellis at the Garden on February 16, 1970, but by then even Ali couldn’t complain: “I can’t blame Joe Frazier for accepting the title under the conditions he did. Joe’s got four or five children to feed.”[13]

Roone Arledge, Howard Cosell, and ABC Sports

In 1968, American Broadcasting Companies approved a plan that called for ABC Sports to be a stand-alone division under thirty-six-year-old Roone Arledge, who thus became “the first sports president in the network television industry."[14] Under Arledge’s reign, ABC Sports became almost a megaphone for Ali during his exile. His most outspoken supporter was ABC’s Howard Cosell, voted in one poll as both “the best-liked and most-hated sportscaster.”[15] But it was Arledge who took the heat for allowing Cosell to use Ali's Muslim name.[16] Arledge said in a later interview: “There was a huge controversy because Howard was the first person I think to publicly call him Muhammad Ali … And people attacked me and I get all this mail and everything, and I finally said, look, somebody with the name Roone has no right to tell anybody what they can be called.”[17] Arledge invited even more outrage when, despite protests from ABC management and the US State Department, he hired Ali to provide commentary during the October 1969 US-Soviet amateur boxing match in Las Vegas.

Arledge helped revolutionize sports broadcasting in the 1960s, bringing technological innovations and a journalistic approach to the changing genre. “ABC’s Wide World of Sports,” which premiered in 1961 and broadcast fringe sports such as arm wrestling, bobsledding, and ski jumping, offered a venue where the relationship between Ali and Cosell could grow.[18]

Arledge had brought Cosell back to ABC in 1965 after a five-year hiatus — the sportscaster, Arledge wrote in his memoir, believed he had been "blackballed" because of anti-Semitism.[19] Cosell, a former attorney, believed Ali had been denied constitutional rights “such as due process and freedom of speech.”[20] Eventually they came to appear as if in the midst of a vaudeville sketch that they had perfected over many years on the road. The two would spar in street clothes. Ali would playfully try to remove Cosell's toupee. Cosell would attempt to tame him with his verbosity. (Cosell: “You're being extremely truculent.” Ali (without missing a beat): “Whatever truculent means, if that's good, I'm that.”[21]) Ali told Cosell that Joe Frazier was fighting for "the Mickey Mouse title.” Ali explained, “I have a belt at home that says world heavyweight champion. And for a man to be the champion he's gonna have to take my belt.”[22]

Dick Schaap: The “Connector”

Dick Schaap was a twenty-sex-year-old sports editor at Newsweek when he first met Ali, just eighteen and a member of the 1960 US Olympic Boxing Team.[23] During a cab ride into the city, Ali told Schaap that he was going to win the Olympic gold, then turn pro and become the heavyweight champion.[24] Schaap had never encountered an athlete like him — “no doubts, no fears, no second thoughts, not an ounce of false humility,” he would later write.[25] Schaap was working for the Herald Tribune when he broke the story that Ali had adopted his Muslim name; his source was the civil rights leader, Malcolm X.[26]

Schaap was what author Malcolm Gladwell would call a "connector," one of those “people with a special gift for bringing the world together.”[27] Schaap became co-host of “The Joe Namath Show,” a weekly half-hour broadcast that first aired in late September 1969 in New York on a local station, WOR-TV, on Friday evenings.[28] Schaap used his connections to book the show’s diverse guests: writer Truman Capote, actors such as Ann Margaret, and athletes of all sorts, including Ali on October 13, 1969.[29] Ali began his appearance by reciting a poem: “I like your show, and I like your style, but your pay is so cheap, I won’t be back for a while.” There was the usual shtick: Namath asking Ali if he were afraid to fight Joe Frazier, and Ali saying that “Joe’s ducking me,” with Namath quickly agreeing: “He still has to beat you to be the champion of the world.” Then there was Ali objecting to the topic broached by the next guest, actor George Segal, who discussed filming nude scenes: “I don’t take part in these type conversations,” Ali said. Schaap apologized afterwards to Ali, who reportedly said: “Aw, man, I got to do that. The CIA is listening, the FBI is listening, everybody’s listening.”[30] But so was a large audience at home — “The Joe Namath Show” was syndicated to more than forty TV stations.[31]

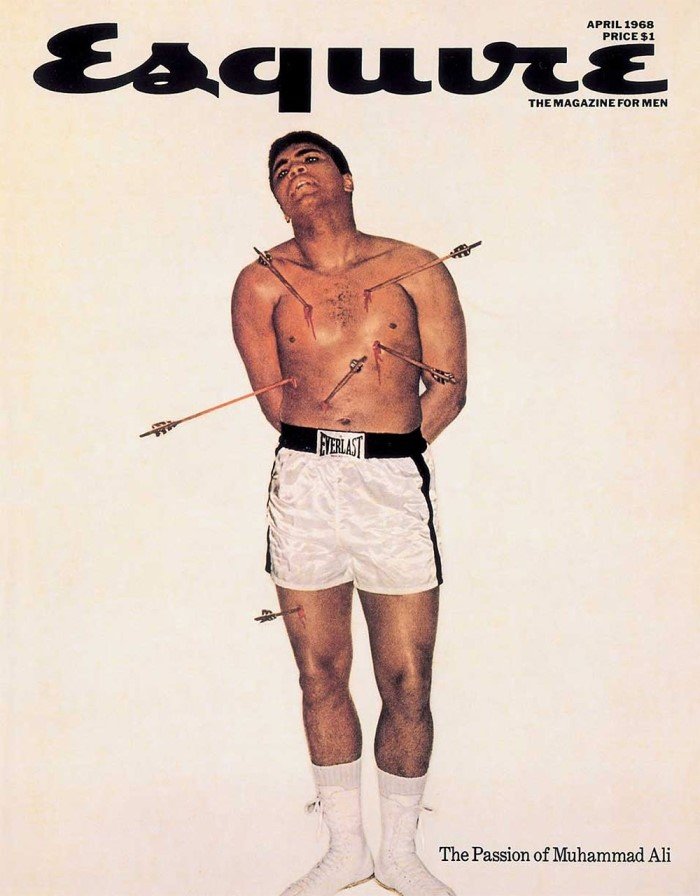

George Lois and an Iconic Magazine Cover

Ali was the subject of an Esquire profile in 1968 when he was paired with advertising executive George Lois, hired by the men’s magazine’s editor in chief, Harold Hayes, to design innovative covers to accompany the magazine’s cutting-edge stories that were reflective of the “New Journalism.”[32] Lois had a single idea he wanted to convey: “When Cassius Clay became a Muslim, he had also become a martyr. I wanted to pose him as St. Sebastian, modeled after the 15th-century painting ...”[33]

Ali agreed to fly to New York for the photo shoot, but he grew concerned when he looked at a postcard of the painting and realized that he was looking at a Christian martyr. Lois told Ali that “St. Sebastian was a Roman soldier who survived execution by arrows for converting to Christianity. He was then clubbed to death and has gone down in history as the definitive martyr.” Ali still wanted Lois to receive clearance by phone from Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. Then the fighter donned his white Everlast boxing trunks and the arrows — which weighed too much to be glued to his bare chest — were dangled from a fishing line hung from a bar above his head. Five arrows appeared to have penetrated his chest and stomach, and a sixth looked like it had penetrated his right thigh; blood seemed to be seeping from his wounds.[34] The shoot took so long that Ali began to name the arrows after those US officials he felt were persecuting him: “Lyndon Johnson, General William Westmoreland, Robert McNamara . . .”

Lois wrote that when he saw the transparency to the photo by Carl Fischer he said: “Jesus Christ, it’s a masterpiece.”[35] A caption at the bottom of the cover read: “The Passion of Muhammad Ali.” The cover ran in April 1968, the same month that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

Ali's Return from Exile

The exiled fighter continued to take bold chances for publicity and much-needed income, earning a weekly salary, a share of ticket sales, and his name, "Cassius Clay a/k/a Muhammad Ali” at the top of a marquee near Times Square when he starred in a Broadway musical, "Buck White," in December 1969 at the George Abbott Theatre. Despite closing after only seven days, Ali generally got good reviews for his performance, which involved wearing a fake beard and Afro in his portrayal of a black activist.[36] Ali appeared on Broadway again the next month, albeit on the big screen at the Cinerama Broadway, one of the more than one thousand theatres worldwide that showed filmed version of a computer-generated "Super-Fight" with the exiled boxer facing former champion Rocky Marciano.[37] The two sparred for numerous one-minute rounds that were filmed not long before Marciano was killed in the crash of a small plane in August 1969.[38] Fans saw the exiled champion knocked out by Marciano, though the BBC received so many complaints about the questionable conclusion that it later broadcast a revised version in which the bigger, faster Ali was the victor. [39] "The people would like to see me fight,” Ali said afterwards, “but the boxing officials and the politicians haven't got the guts."[40]

Ultimately, Ali prevailed when the city of Atlanta granted him a boxing license, paving the way for a victorious October 1970 fight with Jerry Quarry, then, after New York followed suit, his first boxing match at the new Madison Square Garden, where he knocked out Oscar Bonavena. On March 8, 1971, Ali fought Joe Frazier at the Garden, losing the so-called “Fight of the Century” by decision, but cementing a comeback that led to him reclaiming his heavyweight crown. His most important victory came a year later when the US Supreme Court overturned his draft conviction.

Following his comeback fight with Quarry, “ABC’s Wide World of Sports” had the rights to air a tape of the event and Ali was asked to come to its New York City studio to provide commentary. When one of Ali’s representatives started making demands of Doug Wilson, the show's producer, the conversation grew tense until Ali grabbed the phone and apologized to Wilson: "The last three years you have been very good and fair to me. If you want me there ... I'll be there."[41]

With the help of his media allies, Ali had prevailed in the court of public opinion, a vitally important victory in an increasingly interconnected world where evolving technology was allowing news to travel much faster to more people than ever before. In the ensuring years, as Ali’s voice was stilled by the damage inflicted in the boxing ring, his allies became increasingly powerful in that evolving world of media and continued to help burnish the fighter’s legend when he no longer could.

Raymond McCaffrey came to the University of Arkansas in 2014 and now serves as the director of the Center for Ethics in Journalism and an associate professor with the School of Journalism and Strategic Media. He worked for more than twenty-five years as a journalist, including eight years as a staff writer and editor at the Washington Post, and holds a doctorate in journalism studies from the University of Maryland.

[1] Robert Lipsyte, "Clay Fights Folley Here March 22," New York Times, February 16, 1967, 61.

[2] Robert Lipsyte, "Short Right Ends Fight at Garden," New York Times, March 23, 1967, 40.

[3] Dave Anderson, "Ali Rated 17-to-5 Choice Over Quarry Tomorrow," New York Times, October 25 1970, S1.

[4] Robert Lipsyte, "Clay Refuses Army Oath; Stripped of Boxing Crown," New York Times, April 29, 1967, 1.

[5] Christopher Lamb, "Jackie Robinson and the Press," The Huffington Post, April 10, 2013, accessed December 19, 2018. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/christopher-lamb/jackie-robinson_b_3038540.html

[6] Michael Maidenberg, "Ali or Clay?" Columbia Journalism Review 6, no. 3 (1967): 36-37.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Robert Lipsyte, "A Brand New Ballgame?," New York Times, January 1, 1968, 19.

[9] Robert Lipsyte, "The Regulator," New York Times, January 6, 1968, 32.

[10] Ibid.

[11] "Nat Fleischer, 84, Dead; was Sports' 'Mr. Boxing'," New York Times, 26 June 1972, 36

[12] Ibid.

[13] Thomas Hauser, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 208.

[14] Anthony Sampson, The Sovereign State: The Secret History of III (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1973), 88-94; Jack Gould, "A.B.C. Names Network and Sports Presidents," New York Times, January 9, 1968, 87; Jack Gould, "A.B.C.-TV to Pick a New President," New York Times, January 8, 1968, 1.

[15] Robert Lipsyte, An Accidental Sportswriter: A Memoir, First ed. (New York, NY: Ecco, 2011), 80.

[16] Roone Arledge, Roone: A Memoir 1st ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 95.

[17] Roone Arledge, interview for ESPN Sports Century, undated, 1999, transcript, Roone Arledge Papers, 1953-2002, General, MS-1423, Box 4, Folder 4, Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

[18] Marc Gunther, The House That Roone Built: The Inside Story of ABC News. 1st ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1994), 9.

[19] Arledge, Roone: Memoir, 94.

[20] Frank Deford, "'I've Won. I've Beat Them,'" Sports Illustrated, August 8, 1983, accessed March 27, 2019, https://www.si.com/vault/1983/08/08/619506/ive-won-ive-beat-them

[21] FootageWorld, “Ali vs. Cosell - 1968 Interview,” YouTube Video, 5:08, 3 August 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dXbY-CrxO9M

[22] FootageWorld, “Ali vs. Cosell - 1968 Interview.”

[23] Richard Sandomir, "Dick Schaap Dies at 67; Ubiquitous Sports Journalist," New York Times, December 22, 2001, C15.

[24] Dick Schaap, Flashing before My Eye: 50 Years of Headlines, Datelines & Punchlines. 1st ed. (New York: W. Morrow, 2001), 57-58.

[25] Ibid., 58.

[26] Ryan Glasspiegel, “Dick Schaap Did So Much Work,” The Big Lead, May 3, 2017, accessed March 28, 2019, https://thebiglead.com/2017/05/03/dick-schaap-did-so-much-work/

[27] Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. 1st Back Bay pbk. ed. (Boston: Back Bay Books, 2002), 38.

[28] Mark Kriegel, Namath: A Biography (New York: Viking, 2004), 308.

[29] NUMBA1PROSPECT, “Muhammad Ali talks with Joe Namath in 1969,” YouTube Video, 14:03, July 3, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c9an_VWgKO4; Schaap, Flashing Before My Eye: 50 Years of Headlines, Datelines & Punchlines, 64.

[30] Schaap, Flashing Before My Eye: 50 Years of Headlines, Datelines & Punchlines, 155.

[31] Kriegel, Namath: A Biography, 308.

[32] Jonathan Eig, Ali: A Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), 254-255.

[33] Lois, Covering the '60s: George Lois, the Esquire Era, 61; Tim Grierson, "How Muhammad Ali’s Iconic ‘Esquire’ Cover Helped Cement a Legend," Rolling Stone, June 5, 2016, accessed March 30, 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/how-muhammad-alis-iconic-esquire-cover-helped-cement-a-legend-69404/

[34] Eig, Ali: A Life, 256-257.

[35] George Lois, Covering the '60s: George Lois, the Esquire Era, 1 vols. (New York, N.Y.: Monacelli Press: Distributed by Penguin USA, 1996): 61.

[36] "Cassius Clay Musical Stopping the Count at 7," New York Times, December 5, 1969, D5.

[37] “Computer Fight In Theaters Here,” New York Times, January 20, 1970, 38.

[38] Hauser, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, 196; "Marciano-Clay: The Computer Knows," New York Times, January 18, 1970, 183; Joe Nichols, "Marciano Is Killed with Two in Iowa Plane Crash," New York Times, September 2, 1969, 44.

[39] "Congenial B.B.C. Shows Clay Beating Marciano," New York Times, January 30, 1970, 37.

[40] "Clay's Response: Can't Win 'Em All," New York Times, January 21, 1970, 52.

[41] "The Magical Relationship Between Muhammad Ali and Howard Cosell," The Best of Sports Illustrated Live, June 4, 2016, accessed March 31, 2019, https://www.si.com/boxing/video/2016/06/04/muhammad-ali-howard-cosell-magical-relationship