Inventing, and Policing, the Homosexual in Early 20th c. NYC

By Hugh Ryan

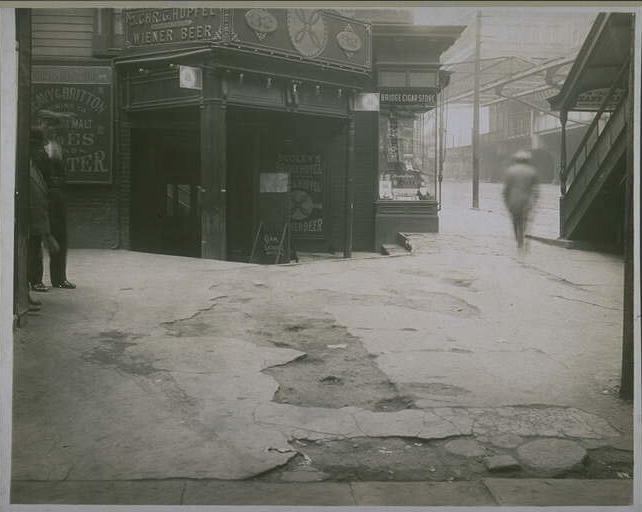

Sands St, circa 1916. (Brooklyn Historical Society)

On January 14th, 1916, when Antonio Bellavicini went to his job as a bartender at 32 Sands Street (near the Brooklyn Navy Yard), he had no way of knowing that before the evening was out, he would be caught up in New York City’s early, inchoate attempts at policing homosexuality. At that time, the Navy Yard area was renowned for its lawlessness and – to those in the know – for its gay cruising. Sands Street, in particular, was so infamous that in 1932, when Charles Demuth painted an image of a john trying to pick up two sailors there, he simply titled it “On‘That’ Street.”

Bellavicini, a thirty-four-year-old, married, Italian immigrant father of five, was ensnared in a sting operation on Sands Street set up by the Brooklyn police and supported by the Committee of Fourteen, a civilian anti-vice group. The Committee had been founded in 1905 to fight the spread of what were called “Raines law hotels” – bars that rented rooms as a way to get around an 1896 law that banned any public institution (other than a hotel) from serving alcohol on Sundays. Since most men only had Sundays off, this was effectively a temperance movement. However, by 1916 the Committee had expanded their purview to include all kinds of vice that took place inside these hybrid saloon-bars: mostly prostitution, but also any kind of same-sex intimacy or gender non-conforming activities. The Committee’s primary method of enforcement was to strong-arm breweries into canceling the contracts of saloons they disapproved of, effectively shutting them down. Since the Committee was composed of many high-standing businessmen and civic leaders, most brewers did as they requested. However, when necessary, the Committee worked directly with the police, as it appears they did in the Sands St. raid.

The bar had been of interest to the Committee for at least two years, after a previous owner had come under scrutiny for allowing gambling on the premises, but it was the police who had them under observation in 1916. According to testimony given by Officer Patrick Clark at Bellavicini’s appeals trial, for four weeks before it was raided, the police had noticed that the “place was frequented by degenerates… men, they were powdered and painted up and their voices feminine.”

So on the night of January 14th, the 149th Precinct chose a novel method of investigation: they dressed Officer Harry Saunders in a U.S. Navy sailor’s outfit, in order to “get the perverts who frequent the place,” according to a letter written by Frederick Whitten, General Secretary of the Committee of Fourteen. (Whitten was discussing the case with Leon Godley, the Acting Commissioner of Police at the time, but the letters don’t make clear what role Whitten or the Committee played in this particular bust.)

Arrest card for Antonio Bellavicini. Committee of Fourteen records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Letter from Frederick Whitten, General Secretary of the Committee of Fourteen, to Leon Godley, Acting Police Commissioner, regarding the arrests at 32 Sands Street. Committee of Fourteen records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

According to testimony from Saunders, in the brief fifteen minutes he was inside the saloon at 32 Sands Street, he was hailed by a group of three men sitting at a table, who called out to him, “Oh, sailor, dear, come over and drink with us.” A few minutes after joining them, one of the men – John Meehan – leaned over and said, “Why, you can come over with us, we want you to come to 170 Schermerhorn Street. If you will come down there we will suck your cock.”

Saunders demurred and moved to another table, where three more men propositioned him. A few minutes later, he and two other officers arrested all six men, as well as Bellavicini, whom Saunders claimed had overheard the proposition. On February 1st, Bellavicini was convicted of running a “disorderly house,” which the penal code defined as “a house of ill-fame and assignation, and a place for the encouragement and practice by persons of lewdness, fornication and unlawful sexual intercourse, and other indecent and disorderly acts and obscene purposes therein, and a place where such practices and acts were committed, and a place of public resort at which the decency, peace and comfort of the neighborhood were disturbed.” For this, Bellavicini was sentenced to three months in the workhouse, which he appealed.

During his second trial, the three police officers began to elaborate their stories. Now, not only had the six men propositioned Officer Saunders, but they had rouged cheeks, blackened eyebrows and were holding powder puffs. Furthermore, claimed Officer William Finken, every man in the back room of the bar was similarly done up, and when they first arrived, “two sailors [were] sitting on the laps of two of these men that were arrested.”

Despite testimony to the contrary from three other patrons – who claimed there were no sailors sitting on laps, no painted faces or powder puffs, and that there had been no proposition – the court upheld Bellavicini’s conviction in a 3-2 split. They even threw out his lawyer’s novel assertion that:

The natural aversion, that the mere mention of a charge such as this creates in a clean mind, prejudiced the distinguished jurists… In other words, the presumption of innocence, to which he was entitled, was denied the defendant from the very start—not, it is asserted, by any disposition of the Court to be unfair to anybody; but the character of the charge awakened their innate hostility to such vice as was alleged, created an irremovable bias in their minds and suppressed their judicial temperament.

Call it an inverse “Twinkie defense:” the idea that queerness is so disgusting that the merest whiff of it would prevent Bellavicini from ever getting a fair trial. And a whiff of queerness – as we would understand it today – is all that was present in this case. Despite the fact that Bellavicini’s arrest revolved around an alleged proposition for gay sex, any discussion of “homosexuality” or “homosexuals” per se is notably missing from the case records. Bellavicini’s own sexual orientation was never discussed during the trial. His conviction was for running a “disorderly house” – the same charge that he could have received for running a brothel, permitting gambling in his bar, or serving alcohol on a Sunday. The six men arrested along with Bellavicini were variously referred to as “vagrants” and “degenerates,” and their conviction was under a statute that dealt with prostitution and loitering. While the police were concerned with what they offered to do and how they looked, the focus was entirely on their actions and bodies, not their sexual orientations or gender identities.

While that might seem pedantic, it’s actually roundabout evidence of a major shift in Western thinking on sexuality in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as evidence of the fascinating lag between our conceptual understanding of “deviance” and our mechanisms for controlling it. The idea that sexuality is a fixed, intrinsic identity, separate from gender, only began to develop in the mid-to-late 1800s, as sexologists in Europe and the United States began to classify people as “homosexuals” and “heterosexuals” (among many, many other terms invented by fin de siècle social scientists). Before this point, while specific acts and desires were still policed, having those desires didn’t generally define you as a person – and therefore, the law didn’t need to define you that way either. But as sexologists began to delineate the “homosexual” as a congenital degenerate from a medical standpoint, regulatory governmental agencies (like the police) needed to do so from a legal standpoint as well.

Historian and social scientist Margot Canaday brilliantly explored the dynamic tension between the U.S. government’s recognition (/definition) of deviant sexuality and its ability to police it in her book The Straight State. Although she focuses on the federal government, her lens could equally be turned on New York City's institutions in the early part of the 20th century. Canaday wrote:

World War II was a watershed moment in the state’s relationship to homosexuality, yet homosexuality was not a new phenomenon for state officials during and after the Second World War. Rather, federal bureaucrats had been aware of traits and behaviors that were coming to be associated with homosexuality for at least half a century. The regulatory response to this before the war, however, was fairly anemic… Federal officials were confronted with evidence of sex and gender nonconformity as they did the things that bureaucrats do – whether keeping undesirables out of the country, peopling an army, or distributing resources among the citizenry. But they initially encountered this evidence without a clear conceptual framework to analyze the problem. Even so, they worried about those whose bodies or behaviors seemed perverse to them. Over time, they worked toward an understanding of what this phenomenon was and why it might be significant, and they made some minimal attempts at regulation. Yet when perversion was policed in this early period… it was often through regulatory devices aimed at broader problems: poverty, disorder, violence, or crime. As the state expanded, however, it increasingly developed conceptual mastery over what it sought to regulate.

Returning to Bellavicini’s case, it seems clear that the police were worried about homosexuality, but lacked a conceptual or legal framework for policing it as a specific identity. However, the development of that mechanism was actively being encouraged (and spearheaded) by organizations like the Committee of Fourteen. A year prior to Bellavicini’s arrest, General Secretary Whitten had taken it upon himself to contact Lawrence Dunham, the Deputy Police Commissioner, about the “pink Transcript,” a free paper that advertised massage parlors. One ad in particular had caught Whitten’s attention:

I am much surprised, however, to notice the continuance of the advertisement by Alberts which reads: Massage for gentleman only. This advertisement aroused my curiosity as long ago as 1909 and I personally called on the individual. I had difficulty in restraining myself from giving him a knock-out blow, for with all my acquaintance with vice, I am glad to say that I have been free from having to deal with sexual perverts.

Whitten wouldn’t stay “free” for long, however. In 1918, two years after Bellavicini’s arrest, Whitten weighed in on a similar case, where a police officer dressed as a sailor had entrapped “male perverts” at a bar at 36 Myrtle Ave. While still judging it a successful mission, Whitten had begun to worry about this kind of entrapment, adding in a handwritten note that using actual sailor uniforms “is in flat disregard to a very important Federal law.”

The problem was this: As “homosexuals” were beginning to be understood as a deviant class, their very existence needed to be policed. But laws like disorderly conduct were designed to be brought to bear against activities, not identities. This was why the police made such a big deal about powder puffs and make-up: Because wearing clothing of the “opposite” gender was an illegal, arrest-able activity. Using sailors to entrap men into unlawful propositions was another way to get around this issue, but – as Whitten pointed out – it was a workaround that came with its own problems. Furthermore, “running a disorderly house” was a broad statute that didn’t actually condemn homosexuality or homosexual acts specifically, making it an inefficient vehicle for budding anti-gay crusaders. To arrest Bellavicini, they needed to be able to claim that he was openly serving patrons who were obviously “disordered.” An overheard proposition might not have been enough; a room full of men wearing make-up was.

In 1923, the New York state legislature came one step closer to a regulatory solution, when they created a specific charge of “disorderly conduct – degeneracy.” According to George Chauncey’s encyclopedic history Gay New York, it was

[t]he first law in the state’s history to verge on specifying male homosexual conduct as a criminal offence. Even statutes against sodomy and the crime against nature, which dated from the colonial era, had criminalized a wide range of nonprocreative sexual behavior between people of the same or different genders, without specifying male homosexual conduct or even recognizing it as a discrete sexual category. The criminalization of male homosexual conduct implicit in the wording of the law was made explicit in its enforcement, for Penal Law 722, section 8, “degenerate disorderly conduct,” was used exclusively against men the police regarded as “degenerates.” Although little evidence remains concerning the history of the legislature’s decision, its timing surely reflects the degree to which the social-purity societies and the police had identified homosexuality as a distinct social problem during World War I.

Once the law was passed, the Committee of Fourteen (and in particular, General Secretary Whitten) kept careful track of it. In a 1925 letter to Samuel Bolton, Deputy Chief Inspector of the 12th Police Division in Manhattan, Whitten wrote that he “discovered that in the first four months of 1925 there had been some 250 arrests by members of the 12th Division, of men upon the charge of Disorderly Conduct – Degeneracy.” He called these numbers “tremendously startling,” and wondered whether they represented “an increase of the evil or increased activity by the police against these offenders.” Like Chauncey, Whitten connected this uptick with World War I, saying “the number of such cases had increased from less than 150 before the war, to something over 750 following demobilization.”

Whitten, however, wasn’t just interested in arresting homosexuals, he was deeply concerned with understanding sexuality – albeit for punitive reasons. At the close of his letter to Deputy Chief Inspector Bolton, he wrote:

[t]here is a feeling, in which all but a few psychologists concur, that the person guilty of such acts – and they are not limited to the uneducated or lower classes – are mentally deranged. I endeavored at the time to arrange for mental examinations of all such persons convicted of Degeneracy in the Men’s Night Court, but as the incidental expenses of this volunteer effort were to be borne by those whom the mayor at the time deemed unfriendly, was not successful… if you think as I do, that this problem is one which should, in view of the large number of cases now before us, have your particular attention, will you not make an appointment with me that we may discuss it? I think I can suggest a solution of former difficulties.

Unfortunately, Bolton’s response is not recorded in the Committee of Fourteen files, and Whitten’s potential solution has been lost to history. However, within a few years, Prohibition would be overturned, giving moral crusaders like Whitten the chance to write specifically anti-gay rules into the newly formed New York State Liquor Authority. Suddenly, in 1933, what had been the imprecise and disorganized policing of same-sex desire would become a full-scale government apparatus designed to harass and eradicate public gay life. Or, as Chauncey put it:

State regulations upheld by the state’s highest court explicitly prohibited gay men and women from gathering in licensed public establishments… the new regulations not only codified the ban on gay visibility but raised the stakes for those who considered violating it. They threated to destroy the business of any bar or restaurant proprietor who served a single drink to a single gay man or lesbian, to close any theater presenting a play with gay characters, and to prevent the distribution of any film addressing gay issues. They explicitly defined one man’s trying to pick up another man as a criminal offense. Never before had gay life been subject to such extensive legal regulation.

Less than two decades after Antonio Bellavicini’s fateful arrest, New York City had developed a stringent, powerful mechanism for policing public gay life – right at the very moment that the idea of a public gay life was literally becoming thinkable (in the sense that it was both socially possible to live as, and conceptually possible to identify oneself as, a gay person). That the police didn’t need these laws in order to persecute homosexuality is obvious – after all, Bellavicini was found guilty (twice) years before these statutes were enacted – but these new laws streamlined the process, and were part and parcel of transforming our idea of queerness from a set of discrete, immoral acts to a permanent criminalized identity.

Hugh Ryan is a queer writer and historian, and the founder of the Pop-Up Museum of Queer History. This post is based on research from the author's larger history, When Brooklyn Was Queer (forthcoming from St. Martin's Press in 2018), as well as a 2018 exhibition at the Brooklyn Historical Society.