“Can’t They Be Separated?” Italian Immigrants and Irish Workers in Gilded Age New York

By Paul Moses

On the warm Monday morning of August 20, 1888, a crowd gathered in the Westminster Hotel at Sixteenth Street and Irving Place in Manhattan to wait in anticipation for the Irish American labor leader Terence V. Powderly to testify in a congressional probe of what the New York Times headlined “The Immigration Invasion.” The hearings, called to probe violations of the contract-labor law, had begun the previous month at the Westminster, a six-story edifice with canvas awnings shading each window and carriages parked outside.

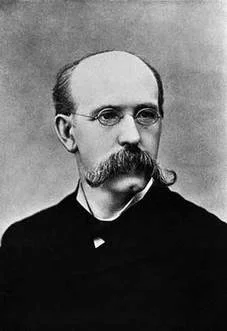

Powderly arrived late, after the first witness was called, and quietly took a seat. Dressed in a worn gray suit, he was a short man with an outsized, bushy, graying mustache that masked his mouth, a prominent, dimpled chin, blue-gray eyes, and gold-rimmed glasses. Powderly led the Knights of Labor, but by 1888, the American Federation of Labor was on its way to displacing his organization as the leading union. Its leader, Samuel Gompers, was in the audience as well.

On the witness stand, Powderly identified himself as the grand master workman of the Knights of Labor since 1879, and a machinist by trade. “What sort of men are admitted?” asked the committee chairman, Representative Melbourne Ford, an energetic, ambitious, thirty-nine-year-old first-term Democrat from the busy manufacturing city of Grand Rapids, Michigan. “We admit all men who work at manual labor,” except those who make or sell “drink,” said Powderly, a teetotaler. “We exclude all bankers and also professional politicians and loafers.”

And what did he mean by “professional politicians”? “A man is a politician if he seeks all the money he can get out of it,” Powderly responded.

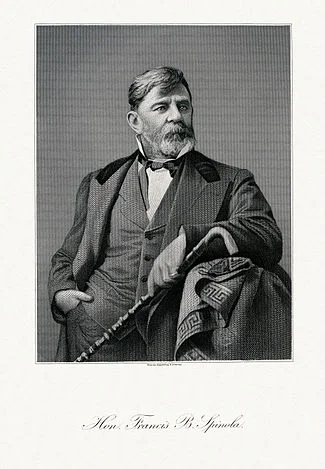

As Powderly established his credentials as a wit, one congressman on the panel shifted uncomfortably in his seat and winced in pain as he moved his “rheumatic” legs, a newspaper would report the next day. That was General Francis Barretto Spinola, a New Yorker who was the first Italian American elected to Congress. Spinola still suffered leg pains from being shot in the heel while he led a charge against a Confederate position in northern Virginia during the Civil War, in which he served as a brigadier general. As for Powderly’s remark about “professional politicians,” Spinola was as partisan a Tammany Hall Democrat as could be, a wily political brawler with a reputation as a born politician.

Congressman Ford, at the time a promising political star, led Powderly with friendly questions. The labor leader recalled the upstanding Irish, Welsh, and English immigrants he knew in his youth and contrasted them with the immoral, unfit newcomers he saw in the present day. His father had come from Ireland with a shilling in his pocket and settled in Carbondale in the Pennsylvania coal country.

Powderly cherished his family’s Irish origins. In his autobiography, he wrote that his father migrated to America in 1827 after serving a three-week sentence in the Trim jail in County Meath for the crimes of shooting a rabbit on a lord’s estate and being an Irishman who owned a gun. Powderly was active in the Irish land reform movement and served as treasurer of the Clan na Gael, a secret Irish American society dedicated to overthrowing British rule of Ireland. He was involved enough in the Irish cause that a former British spy who infiltrated Clan na Gael once claimed in a book that he heard the union leader advocate burning down English cities in retaliation for offenses against the Irish. “I am in favor of the torch for their cities and the knife for their tyrants,” Henri Le Caron quoted Powderly as saying during a heated Clan na Gael meeting in Chicago. Powderly, alerted to the book by the Irish nationalist Michael Davitt -- whom he had made an honorary member of the Knights of Labor -- denied the account and threatened to sue for libel if the book, published in London, were printed in America. He maintained that he was at the meeting but did not speak.

Powderly noted in his autobiography that as a young man, he bought a Remington rifle and bayonet to go to war in the Irish cause. But when a friend who was a native of England died, he sold the rifle and bayonet to raise money for the man’s wife and children. Powderly quipped that if his rifle didn’t help to free Ireland, at least it helped to bury an Englishman.

The union leader told the committee that the Irish and other northern European immigrants from earlier in the nineteenth century differed from the newcomers. They came to stay, became U.S. citizens, and owned their own homes instead of renting, he testified. Now, he complained, more than half of the coal miners were foreigners. The new immigrants were “too low” to make good citizens. “They retain their own manners and customs until they die, or may go back to their own lands.”He accused the immigrant workers of having loose morals, asserting that it was common for eight to ten workers to live in a house with one woman who took care of all their needs. “Not the wife or mistress either, but she served all purposes,” Powderly testified. “I don’t know what you would call it; you know what I mean.”

Congressman Ford pressed for the racy details. “A wife in common for the whole crowd?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” Powderly replied.

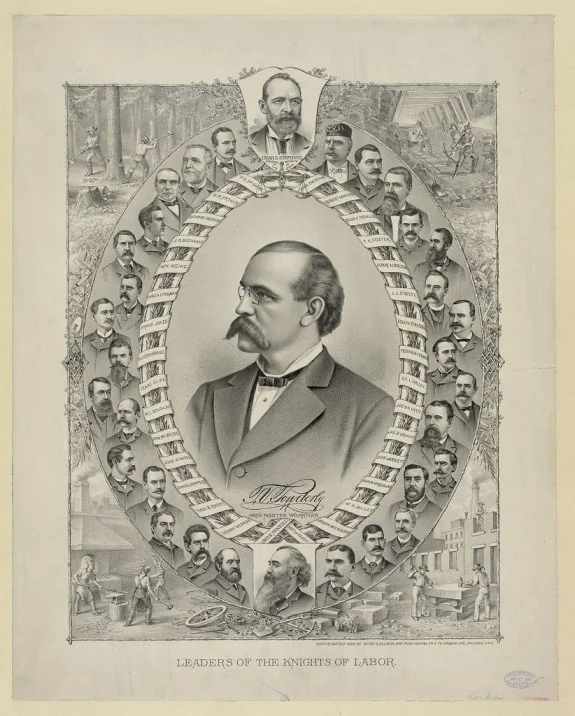

Terence V. Powderly, center, with leaders of the Knights of Labor. His predecessor, Uriah Stephens, is at the top, center, and P. J. McGuire is to Stephens’s left. Lithograph by Kurz and Allison, circa 1886. Library of Congress.

At that point, the country’s first Italian American congressman, Frank Spinola, spoke up. The unstated implication behind Powderly’s tale of immorality was that the people involved were Italian. As the Times had noted, the investigation “seems to be more interested in Italian immigration than in that of any other nationality,” even though the committee had insisted that no nationality was being targeted.

Spinola was not known for defending Italian immigrants. The blue-eyed, white-bearded congressman was half-Irish, and moved easily through the Irish-dominated world of Tammany Hall politics. His paternal grandparents were Genoese; his father, John Spinola, a farmer and oysterman on Long Island’s North Shore, had migrated from the Portuguese island of Madeira. His mother, Eliza Phelan, was descended from Irish immigrants and said to be the daughter of a captain who fought under George Washington in the American Revolution. When it came to being one of the boys, Powderly had nothing on Frank Spinola, a former Brooklyn fireman who loved staging big parties at his country mansion in Setauket, Long Island, going to the Saratoga horse races, watching illegal prizefights, and especially playing draw poker, at which, according to the Brooklyn Eagle, he “almost invariably won.”

Spinola decided to call Powderly on the card he had played with his story about the woman with multiple husbands. “Where did that state of facts exist?” he asked.

“I saw them in the city of Cleveland. This lady told me this two years ago,” Powderly answered.

Spinola: “The woman herself told you that?”

If it seemed ridiculous that an immigrant woman in the Victorian era would tell an American stranger she was having sexual relations with eight men, Powderly’s unflinching response gave no indication of it: “Yes, sir.”

Finally, Spinola worked his way to the question it seemed he really wanted to ask from the outset: What was the woman’s nationality?

“There are a good many Polanders who become good citizens,” Powderly responded.

Congressman Ford, who was leading the committee with the goal of clamping down on immigrant labor, stepped in to rescue Powderly from Spinola’s questions and then upped the ante by getting him to claim that the immoral living conditions he allegedly witnessed in Cleveland could be found among immigrants in “a great many places.”

“State whether they know what a home is as an American workman understands it,” Ford told him.

“They have no conception of home as an American workman understands it,” Powderly declared. He told the committee that the immigrant laborers he had seen would never make decent citizens. They had to be identified by numbers clipped to their pants because “it is impossible for an English person to speak to the men to be able to pronounce their name.”

Powderly agreed with Ford that immigrants must be able to speak English -— “nearly all our Germans do,” he added. But Spinola was playing on his home field; the hearing was not just in his district, but in the hotel where he resided. So he stepped in once more even though it wasn’t yet his turn to ask questions. “I thought your declaration was rather a broad one,” he told the labor leader.

Powderly wavered. “I don’t mean that, but I would have our American consuls abroad examine into the character of those who come over,” he said, adding that he believed that immigrants must learn English to become citizens. When Spinola’s turn to ask questions arrived, he pressed Powderly further for his views on Italian immigrants. The witness responded that Italians “were not the right class to become citizens.”

Spinola: “Leaving that question entirely out, are they an industrious class of people, as far as your observation has gone?”

“They work as a horse does; they are industrious in the same sense that a horse is -- because he is driven to it,” Powderly replied, before returning to talking of Hungarians.

“I am speaking of the Italians,” Spinola reminded him, trying to make the point that if the Italians came to America voluntarily and not under labor contracts that chained them to low wages, they should be accepted.

Although Powderly already had argued that Italians would make poor citizens, he accepted Spinola’s point. “If he knows how to come we have no objection,” he said, adding that in a union, it didn’t matter where a worker came from, “whether from Ireland or Scotland.”

“We don’t want it to appear in this investigation as if we were aiming our arrows at any nationality,” Spinola concluded.

Frank Spinola did not ordinarily demonstrate pride in his Italian roots. For the most part, the constituents in his long political career were Irish or German. He was born in Stony Brook, New York, in 1821 and came to Brooklyn at the age of sixteen to apprentice as a jeweler. His road to political popularity started when he led a Brooklyn firehouse; he was elected an alderman at the age of twenty-two. He remained proud of his years in Engine 4, wearing his shirt collars high in the style of firemen and thus popularizing a look called the Spinola collar. Spinola moved up to the State Assembly and then the Senate. Although he had steadfastly opposed the abolitionist movement, he threw himself into wholehearted support for the Union effort in the Civil War.

Spinola recruited a brigade that he led as brigadier general. While his military leadership skills were suspect, he fought with valor as the Union army followed General Robert E. Lee into northern Virginia from Gettysburg in 1863. He was shot twice while leading a successful charge at Wapping Heights. The following year, however, he was tried in a well-publicized court-martial on charges stemming from a riot in King’s County’s East New York section in which his recruits rebelled at his failure to pay them a promised bounty. He was accused of recruiting men while they were intoxicated. Ultimately, the charges were dropped and he was discharged honorably in 1865. After the war, he moved to New York, then a separate city from Brooklyn, and quickly moved up the ranks of Tammany Hall, becoming leader of the Sixteenth District, the “Gas House District,” later known as Gramercy Park.

“To think of Tammany Hall without Gen. Francis B. Spinola is pretty much like thinking of Gen. Spinola without his great shirt collar,” the New York Times commented. From boss Richard Croker, a native of Clonakilty, County Cork, to the rivals vying for his own leadership post, Spinola dealt day in and day out with Irish politicos. When he presided over meetings of Tammany’s Sixteenth District Association, he used Irish songs to build his foot soldiers’ enthusiasm. In October 1886, Tammany gave Spinola the nod to run for Congress after Abram Hewitt left his “Gas House District” seat to run for mayor as a Democrat. (Hewitt won but was driven from office when the Irish turned against him in the 1888 election for refusing to observe the Saint Patrick’s Day Parade or fly the Irish flag over City Hall on March 17. Hewitt would not attend ethnic parades or fly any other nation’s flag, an essentially antiimmigrant stance that cost him the mayoralty.)

Spinola’s rough-and-tumble years as a state legislator and controversial Albany lobbyist led to scathing criticism for his congressional candidacy. “If ever Spinola was on the right side of anything it was because somebody made it worth his while to be,” the Tribune declared. But the “Wonderful Shirt Collar,” as the paper dubbed Spinola, won election to Congress by a margin of 469 votes.

In Congress, Spinola was known for supporting Civil War veterans. His signature issue was the quest for federal funding to build a monument in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene section to the Revolutionary War soldiers who died in British prison ships in the East River. Memorializing victims of the British was a cause that Irish Americans appreciated; Spinola pushed it constantly.

There was no such political upside to his defense of Italian immigrants. His success was founded on alliances with Irish politicians. The Italians, who were crowding into the Lower East Side, had not yet found their way in great numbers to his Tenth Congressional District, which roughly spanned Fourteenth to FortySecond Streets, between Seventh Avenue and the East River. While no one would call Spinola a statesman, he did stand up for the Italians and other immigrants.

He took his stand when Congressman Ford’s committee released a scathing report that urged new restrictions on immigration. Echoing Terence V. Powderly’s testimony, it assailed the immigrants being imported into Pennsylvania’s coal regions by way of New York:

They are of a very lower order of intelligence. They do not come here with the intention of becoming citizens. . . . They live in miserable sheds like beasts; the food they eat is so meager, scant, unwholesome, and revolting, that it would nauseate and disgust an American workman, and he would find it difficult to sustain life upon it. Their habits are vicious, their customs are disgusting, and the effect of their presence here upon our social conditions is to be deplored. They have not the influences, as we understand them, of a home; they do not know what the word means; and, in the opinion of the committee, no amount of effort would improve their morals or “Americanize” this class of immigrants.

The report prompted angry remarks in the Italian Parliament; one member said there was widespread dislike for Italians because of biased coverage in New York newspapers. As he released the report, Ford proposed an immigration law that would charge newcomers a five-dollar tax; limit the number of passengers per ship; and exclude those who did not intend to be U.S. citizens. Spinola dissented, agreeing only to accept a one-dollar tax on immigrants to pay for government costs.

Ford’s bill didn’t pass. But, as the Times editorialized, the congressional investigation “is pretty sure to mark the starting point of a new policy on the subject of alien additions to our population.” Both houses of Congress set up permanent committees to investigate immigration. Finding ways to restrict the flow of the poor from southern Italy would be a primary concern for decades to come, leading to a 1924 law designed to curtail immigration from southern, central, and eastern Europe.

***

Irish animosity to Italian workers stemmed from an economic rivalry that the city’s business establishment exploited. As early as 1855, 86 percent of the city’s laborers and 74 percent of the domestic workers were Irish-born. So were more than half of the masons, bricklayers, and plasterers. The immense number of Irish newcomers overwhelmed other groups, such as African Americans, much as the mass of low-wage workers from southern Italy would start to elbow out the working-class Irish in the 1880s. Irish workers quickly saw the advantage of unions and viewed African Americans, and then the Italians, as strikebreakers. In 1874, with Italian immigrants arriving in a trickle, the Times editorialized with approval that their presence was helping employers to reduce wages. Unlike the Irish, the article noted, the Italians “have nothing to do with trades-unions,” working without complaint for a company that brokered the trip from Italy for a percentage of wages and sold them their food, “as the Italians have their own tastes in the culinary direction.” The newspaper suggested that employers hire Italians freely since they were accustomed to low wages.

“The Irish malcontents among the laborers can do little injury to the Italians, and the authorities will protect employers in their rights,” the Times said. The managers of the New-York Italian Labor Company, which brokered the Italians’ employment, responded with a letter to the editor that thanked the paper for its observations. It boasted that the Italians labored at 20 percent below the usual wage.

Obviously, this played poorly with the Irish, who had turned to unions to break out of poverty. The boycott and other traditions of Irish resistance to the British helped to shape Irish Americans like Powderly as labor leaders.When New York’s first Labor Day parade was held on September 5, 1882, it was clear that the Irish played an outsized role in the union movement. Cigar makers, typographers, printers, bricklayers, masons, shoemakers: ten thousand people marched eight abreast beneath the hot sun to the music of twenty bands, carrying flags and placards to Union Square. The sidewalks were thronged with onlookers, some of whom joined the parade. Flag-draped wagons rolled along with the marchers, many of whom smoked cigars. The union leaders present had such names as McCabe, Davitt, Curran, Ryan, Hickey, Cunningham, Burke, Fitzgerald, and Coughlin. Terence V. Powderly was there. So was Peter J. McGuire, who had come up with the idea for the parade.

The march was a show of force after a labor defeat in a nearly eight-week freight-handlers’ strike in the waterfront rail yards that summer. Peter J. McGuire, or P.J., born to Irish immigrants on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1852 and a founder of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, later told a congressional committee that Italian workers shipped into Castle Garden, the immigration entry point before Ellis Island opened, had played a key role in breaking the strike. “They brought over hordes of Italians -- Calabrians from the mountains of Calabria -- in the holds of vessels and transported them from Castle Garden across to the railroad docks in Jersey City and along our piers here, and put them to work,” he testified in New York on August 29, 1883. “Those men, Italians and others, slept in the holds of the vessels and were fed there, and were not allowed any liberty at all; they were in fact prisoners.”

The 1880s were a time of economic expansion. With railroads spreading across the West and the robber barons making big money on Wall Street, Manhattan’s business districts filled with top-hatted men of means. By 1890, Joseph Pulitzer erected a 309-foot tower, the world’s tallest building, on Park Row for his New York World.

There was progress in the job market for both Irish and Italian immigrants. “The Italian scavenger of our time is fast graduating into exclusive control of the corner fruit-stands, while his black-eyed boy monopolizes the boot-blacking industry in which a few years ago he was an intruder,” the journalist Jacob Riis wrote in 1890. “The Irish hod-carrier in the second generation has become a bricklayer, if not the Alderman in his ward.” But although Irish success was visible, it is important to note that for decades, there were large concentrations of the Irish in menial jobs. The New York Irish had once driven blacks out of jobs as laborers and craftsmen, creating tensions that exploded in the draft riots during the Civil War. In 1883, three-quarters of the construction laborers in the New York area were Irish. Ten years later, three-quarters were Italian. With such a rapid ethnic transformation of the workforce, it’s not surprising that Irish workers were bitter toward Italians willing to do their work for less pay.

Of course, the Italians were not the only immigrants arriving in big numbers. There was a wave of immigration from throughout southern and eastern Europe, especially Jews from Russia. But the Jewish migration was very different from the Italians’. As a result of discrimination dating to medieval times and, more recently, due to the laws of tsarist Russia, Jews were not ordinarily farm laborers. Nor did they live in rural areas. For the most part, Jewish newcomers lived in cities and towns, and were tailors, shoemakers, peddlers, garment makers. But both the Italians and the Irish came mostly from impoverished rural areas and sought out the urban equivalent of farm labor: heavy lifting on the docks, unskilled construction work, and excavation. The Irish had achieved civic power by the 1880s, but many of the men still worked as laborers.18 As a result, Irish-Italian “race riots,” as they were called, became common in the 1890s, especially when financial turmoil in 1893 heightened competition for jobs. On April 18, 1892, Irish and Italian longshoremen went at it on the docks at the foot of Joralemon Street in Brooklyn, a spot that looked out on the new Statue of Liberty in the harbor, after an Irishman knocked the pipe from an Italian’s mouth. The Italians ducked stones and cart rungs as they ran away from seventy-five to a hundred Irishmen. They returned to hurl coal and cinders at the Irish, who heaved bricks in return.

Violence also plagued work on the Brooklyn rail system that would provide a name for the pride of Brooklyn, the Brooklyn (trolley) “Dodgers.” Before the streetcars could be dodged, the rails had to be laid—if only the separate Irish and Italian work crews could refrain from fighting.

On September 24, 1893, a “race war” broke out on Flushing Avenue when an Irish foreman ordered his men to redo a section of rail the Italians had completed, according to the Eagle. “After several men had been knocked down the Irishmen were reinforced by some of their compatriots in police uniform and the fight was stopped by the arrest of twenty Italians.” The paper needled, “the Italians will be arraigned before an Irish police justice and will receive punishment befitting their crimes.”

The underlying problem behind such fights, the newspaper said, was that the time had passed when “the heavy work of this country was done by men of Irish birth.” If so, Irish workers had not gotten the notice. The same day the Eagle recalled the bygone days of Irish labor, Irish and Italian crews installing track at Hudson Avenue and Nassau Street in Brooklyn fought it out near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Tensions had been smoldering for days. They flared when the brawny Irish foreman, John Cusick, told the Italians that a curved rail they were about to spike was not straight and needed to be taken up. The Italians’ foreman, Joseph Sugaretto of 64 Smith Street, told his men to disregard the order, and the two bosses started swearing at each other. Some news accounts said Sugaretto punched Cusick, touching off the fracas. Others said that as they prepared to fight, the Italians rushed Cusick, and the Irish retaliated, with both sides using their picks, crowbars, and shovels as weapons. Some of the Italians went up to a nearby tenement roof, dislodged bricks from the chimney and threw them at Irishmen, felling them. Irish onlookers joined the battle, and the twenty-five Italians fled down Nassau Street with about a hundred people in pursuit, raining stones upon them. Police finally intervened and, according to the Times, “without waiting to learn anything about the merits of the case . . . attacked the gang of Italians with their clubs.” Twenty Italians were led away to the stationhouse, trailed by the Irish.

Afterward, the recording secretary of an Italian American Democratic club wrote to the Eagle suggesting that honoring the Italian independence day would help solve the problem. The forty-year-old Italian-born clerk Gerard Antonini urged that

the Italian tricolor . . . be permitted next year to float alongside the American flag on the Brooklyn and New York city halls on the 20th of September as the Irish flag is always raised very prominently on St. Patrick’s day. Let us indulge the hope, as well, that these conflicts between Irish and Italian laborers will cease and that the day is not far distant when they shall shake hands over the bloody chasm . . . and fraternize as they should.

Despite Antonini’s hopes, fights between Irish and Italian laborers became so common that the Eagle ran an editorial headlined “Can’t They Be Separated?” The paper urged contractors to “keep their gangs of workmen distinct -- the Irish in one street and the Italians in another.”

But Irish-Italian resentment continued. One example is a battle fought on a Manhattan construction job at 412–414 West Thirty Seventh Street, a few doors down from a police station, on July 13, 1896. The Italians had complained bitterly that the Irish foreman, James Foley, gave the Irish light duty. That seemed especially so when it came time to mix mortar. The job required two workers— one who sweated it out stirring lime and sand, the other who stood by with a hose, keeping the mix moist. After their lunch break, Foley told an Italian worker, identified in news accounts (which almost always spelled Italian names wrong) as Sandel Sandow, to mix the mortar while an Irishman, Patrick Smith of 334 West 49th Street, would handle the hose. The two workers began to argue, and Sandow splashed the lime around with his hoe.

“Be careful, you dago,” Smith said, and hosed down Sandow’s shoes. In a flash, the two men started pummeling each other, and the rest of the thirty workers joined in while local residents piled out of the tenements and cheered. Bricks, ready at hand, were hurled back and forth, breaking ten windows on the street. It took police, billy clubs drawn, a half hour of effort to break up the fight and arrest six men, including the two men who started it. Smith was bruised from being thrown headfirst into a cellar. “Irish Fight Italians,” one headline put it.

Such battles between Italian and Irish laborers helped create poisonous resentments that leached into other areas of the Irish-Italian relationship: in the church, in politics, in police-community relations. Yet it began to become clear that both sides needed each other, if only for economic reasons. The Italians needed to become part of the labor movement to break out of the exploitation they suffered. And by the early 1900s some Irish labor leaders realized that they needed to bring workers from the new wave of immigration into their fold, if only so they wouldn’t break strikes. But the battles were far from over...

Paul Moses is a Professor of English at Brooklyn College, and formerly an editor and writer at Newsday's city paper. This is an excerpt from his new book, An Unlikely Union: The Irish and the Italians, published courtesy of NYU Press.