Bread and Puppet Theater in Gotham

By Erik Wallenberg

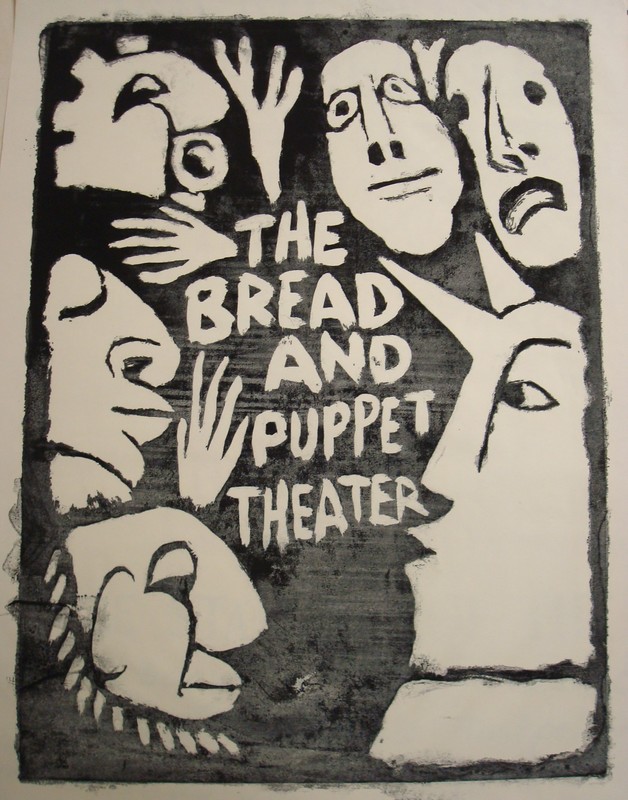

An early poster for Bread and Puppet Theater (Bread and Puppet Theater Collection, University of Vermont Libraries Special Collections).

On May 15, 1962, in New York City’s Judson Memorial Church, an audience assembled to see Peter Schumann’s first production in the United States, Totentanz, The Dance of Death. Schumann, a German immigrant who moved to the United States the year before, created and directed this performance as part of the Living Theatre’s General Strike for Peace.[1] The performance had been rejected for production by the dance dancer Merce Cunningham, prompting Schumann to produce it himself. The reviews called its intent “pagan exorcism” that is “capable of leading you into…many strange thoughts.” Schumann saw the dance as a resurrection of those performed throughout the Middle Ages in European churches, as “the new execution of the old rite.” He called it a “wild feast against death” and an “exhalation of common life to dance” in which the audience is encouraged to put on masks and interact with the performers.[2] The review in the Village Voice described it this way:

Voices, a drum, violin, trumpet, flute, saxophone, tambourine, harmonica, bells, and someone clapping his hands are used as instruments to produce sounds in alternating currents of funeral dirges, kindergarten bands, primitive rituals, and a diabolic symphony warming up. Throughout the performance the participants… all wear ghostly gray-white masks that create an instant supernatural atmosphere of impending doom. The lighting is stark and effective. The performers, most of whom are barefoot, display a… schizophrenic follow-the-leader type choreography.[3]

The sound, masks, and movement took central importance in the work Schumann came to develop after this production. The use of ritual and the aura of an ancient, dark, and simple world became central to the work of Bread and Puppet Theater, especially in relation to the Vietnam War and its attendant death and destruction.

Bread and Puppet Theater is one of the longest running theater companies in U.S. history. From its first days in 1963 performing for rent strikes in Greenwich Village, to the massive demonstrations against the Vietnam War at the height of the 1960s rebellions, to the Nuclear Freeze protests of the early 1980s, the group has produced larger-than-life theater in the streets and in theaters around the world. For Bread and Puppet, early performances were staged wherever the group could find a space, including tenements, lofts, and churches in Greenwich Village. Bread and Puppet found a home in New York City that allowed the group to an affordable existence, a large audience both in the theaters and in the streets, and a community of performers that nurtured a growing radical theater scene.

Bread and Puppet anti-war parade, New York City, 1967.

Bread and Puppet Theater formed in the political and social opening that marked the challenges to cold war culture that would become the hallmark of the 1960s. New York City was the center of the Avant-garde scene with the Performance Group’s “Happenings,” the Living Theatre’s “anti-art aesthetic,” and Ellen Stewart’s La Mama Café.[4] Peter and his wife Elka settled into the middle of this scene in a small tenement on Delancey Street in Greenwich Village.[5]

During the summer of 1963 Peter created “life masks” for sale at Coney Island. Setting up on the boardwalk, a passerby could have a mold made of their face and then, for a small fee, Peter would create a fine plaster mask from the mold.[6] While creating these masks, Peter began to consider a project that would bring together sculpture and his love of dance and movement in the form of puppetry. By the fall of 1963, Peter had created a puppet show of movement and music. The puppets were life sized and made of papier-mâché, held together by wire, and carried by rods that performers placed over their bodies as they moved around stage. Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets, described Schumann’s art this way. “Peter is basically a sculptor, and his figures are highly stylized and detailed forms. He uses puppets…together with human figures…presented on stage in a way which is neither puppetry, dance, nor theater,” Henson wrote, “but an entirely new form of art incorporating elements of each.”[7]

The play, “The Puppet Christ,” later transformed into “The Crucifixion,” was the first show that listed Bread and Puppet Theater as a performing group. An Easter show about the crucifixion of Jesus seems an appropriate theme for a performance group that provides a kind of communion — its signature sourdough bread — to its audience.[8] With this initial success, Bread and Puppet was born. Though the original troupe of puppeteers was made up of Charlie Addams, Irving Doyle, Bruno Eckhardt, Eva Eckhardt, Robert Ernstthal, Elka Schumann, and Peter Schumann, and continued as such until 1968, Peter became the central figure organizing and directing the Theater.[9]

Anti-War Performances

Stefan Brecht argued that the “youth rebellion (was) nothing to (Schumann), the Peace Movement was all.”[10] Schumann’s first critical success came with Fire, an anti-war production dedicated to three American anti-war activists who killed themselves by self-immolation in opposition to the U.S. war in Vietnam. Inspired by the footage of Buddhist Monks carrying out the same protest, these acts were an inspiration for Schumann. Schumann espoused a strong distaste for violence and celebrated non-violent resistance in the face of war and racism.[11]

The Village Voice’s Robert Nichols compared Fire to Picasso’s mural Guernica in its fusion of passion and ruggedness. On stage were two rows of figures all in the same mask of a Vietnamese woman, plaster white, cloaked in black. Some of the figures are puppeteers wearing the mask; others are stuffed and operated by the puppeteers next to them. The aim of this set-up is to make it hard to tell which are human and which are not. A bell tolls and a sign indicates “Monday.” The play moves through the week with various talking and movements of ordinary life. On “Saturday” the silence of the other scenes is shattered by the “horrible noise,” the “shrieking, metallic whine and roar like the noise of a siren and the splintering of bone. A light on stage swings wildly in all directions… the figures slowly swath the others in dark red bands.”[12]

Puppeteer Bob Ernstthal remembers the response being “always the same way… we closed the curtain at the end and there would be this silence, as if there was no one there. I mean they could have been standing packed in the back, packed in the entranceway, you know. People stuffed in the theater. And there was this silence. Dead silence. And maybe after a few minutes you’d hear somebody clap… It was so powerful… There was something there that was really stirring.” This reception, the packed house, and the awe with which people were moved by such simple yet dramatic theater secured a place for Bread and Puppet in both New York City’s radical theater scene and the activist community of the Old Left, civil rights activists, and religious pacifists. Bread and Puppet appealed to members of these groups because the show was “in step with the time.”[13]

Schumann believed that the abstraction of puppets, watching something that was obviously not real, could allow an audience to think about the ideas presented in a more objective way. “Yes. Alienation is automatic with puppets. It is not that our characters are less complex. They are just more explicit.”[14] The alienated relationship of puppets to people meant he could convey a bigger message than he could with actors. “Look at Uncle Fatso” says Schuman. “He is a big puppet with a ring on his finger, he looks like (President Lyndon) Johnson. He looks like everyone's uncle that no one likes. During the Peace March most of the right wing groups were peaceful. But when they saw Uncle Fatso they jumped at him. They went crazy.”[15] People could identify clearly what Schumann was trying to convey with this puppet; not through dialogue or sound, just by seeing the construction of a figure that so clearly captured the corruption and arrogance of power at the center of the U.S. political system. And his name, Uncle Fatso, in a childlike and clear way, captures the feeling of greed, gluttony, and arrogance that Schumann wanted to draw attention to.

Uncle Fatso, Bread and Puppet Museum, Glover Vermont (Erik Wallenberg).

Schumann’s combination of puppet representations of soldiers and political figures combined with the actual words of these figures created a damning result. “When I use a Johnson Speech, I use it for documentation, not satire,” said Schumann. “I like documented dialogue and narration; it has a substance that invented stuff can’t have.” He used this basic language, taken from actual speeches and dialogue, because it created a minimal amount of barriers to the theater while highlighting the political reality he aimed to expose. “A theatre is good when it makes sense to people. I’ve seen a number of groups who seemed more interested in insulting people than in getting to them. You can’t simply try to shock an audience. That will only disgust them. And it is cheap.”[16] Schumann’s intent was not to show how much he knew or how smart he was, he wanted to reach an audience to make them think and perhaps to change their minds.

Puppet Parade

In order to reach more people, Schumann embraced the ideas of traditional European puppet theater that addressed the public in the marketplace and started a community discussion.[17] Schumann’s marketplace was the New York City street. The parade is a way to take art out of its specialized zone and bring it into the street. Peter Schumann argues that the parade is the most basic form of theater. It is a quintessential part of American history, from the giant New York City Thanksgiving Day parade to the countless small-town parades celebrating everything from Independence Day to local culture and history. Bread and Puppet Theater began participating in parades in order to reach an audience, but Schumann found that speaking to those audiences could be the biggest challenge because parade audiences do not generally come to be instructed.

Bread and Puppet Theater, Coney Island (Bread and Puppet Theatre Archives, UC Davis Special Collections Library).

The street theater and parade form that became a hallmark of Bread and Puppet called for puppets that could be easily seen. The issues the group was concerned with — war, poverty, racism — required an amplified expression. Giant puppets offered Schumann and his corps of painters, sculptors, and puppeteers a way to convey their ideas on a grand scale, and be noticed. By 1965 the group was being recognized. Jim Henson thought Schumann was “doing some of the most exciting and unique work in puppetry today.”[18] Bread and Puppet had also begun to win international support with awards from foundations in Mexico and Germany that included requests for performances around the world.[19]

The group left a strong impression on those who witnessed a performance. A thank you letter from the Lower Eastside Mobilization for Peace Action (LEMPA), in response to the Theater’s participation in the 1967 Stop the Bombing Rally and Parade, offers a good example. Ester Gollobin, an organizer for the rally, suggested that Bread and Puppet was essential to drawing in large sections of the neighborhood which otherwise may not have noticed the demonstration. “The plane, the drum-music accompaniment, and the actors themselves—all combined to make a vivid impact on the thousands of East Siders who watched us walk from East Broadway, along Clinton Street, and in and out of various streets until we reached 14th St. and turned down Second Avenue to St. Mark’s Church,” she wrote. “I will personally never forget the sight of people watching from the fire escapes, windows and stoops, and—more importantly—that on this march more neighborhood youth joined the ranks of parades and leaflet-distributors then for any other local peace action. Again—our thanks for your unique contribution to the peace movement.”[20] Bread and Puppet was able to connect to local communities through its presentations of puppetry, music, and spectacle that demanded consideration of questions of war and peace.

Peter and Elka Schumann, Bread and Puppet Farm, Glover Vermont (Erik Wallenberg).

It is not as if Bread and Puppet could create this movement on their own, but they could interact with an already angry and restless population, sharpening their vision and focusing their attention. “What made us successful in the streets was that there were so many people who wanted to protest. And all they knew was ‘okay, you print a leaflet and you go and you hand it out to people. Or you paint a poster and you say what you want to say and you carry it in the street.’ And we said, ‘NO, you can do much more. Come and join us, and we will make a giant spectacle.’ And we had hundreds of people marching down Fifth Avenue.”[21]

Schumann was also beginning to attract the New Left, remembering when the Theater “started walking out in ’64 against the war in Vietnam.” This later grew, “where it looked like a totally political and social united big movement, where even big unions participated and large groups of students participated.”[22] Bread and Puppet was deeply involved in the radicalization taking place around the world. Bread and Puppet’s next critical success was not focused on Vietnam specifically. Like Fire it evolved from a street protest. While Fire was likely expanded from a silent vigil performance, where the masks of the Vietnamese woman were used, A Man Says Goodbye to His Mother originated in an anti-nuclear parade on Hiroshima Day in 1966. The performance follows a soldier as he leaves for battle. After being shot and after bombing, burning, and destroying villages and poisoning crops, a women villager, in a mask of the Vietnamese women, stabs and kills the soldier, showing a victim’s response to U.S. aggression.[23] Theater is not constructed to portray a fairytale, but to convey reality, “to throw reality in people’s faces,” says Schumann. “We want people to deal with it, because ultimately we are responsible for it.”[24]

Vermont Bound

As the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s was waning, the New York City theater scene was professionalizing, and many of the movements for social change fractured, the Theater moved from its home in New York City to Vermont. Since then Bread and Puppet has continued to produce “cheap art and political theatre” engaged in the pressing political questions of the moment.[25] Bread and Puppet established a theater that engaged in the issues of the day—the political debates and social upheavals—and in so doing created a space for community consideration of these issues. New York City in the 1960s saw a flourishing of radical theaters addressing pressing social and political concerns. There were spaces for radical art in the streets and locations like Judson Memorial Church as well as an audience in the midst of throwing off a cold war culture that had long stifled dissent. The theater produced by Bread and Puppet became a space for collective consideration of society. The interplay of art and politics was the tension that helped the group forge a new kind of theater. Through a combination of engaging with the politics of the day and creating oversized street performances Bread and Puppet has continued to maintain relevance, and hence an audience, for over fifty years. Bread and Puppet return regularly to New York and can be seen in the small theaters and churches when not busy leading a protest parade down the streets of Manhattan.

Erik Wallenberg is a PhD Candidate in History at The Graduate Center and teaches at Brooklyn College. He is at work on a dissertation about radical theatre groups and performances dealing with environmental concerns across the United States in the twentieth century.

[1] Nat Winthrop, “Rad Company: Vermont’s Oldest Activists are Still Talking Bout a Revolution,” Seven Days, July 18-25, 2001.

[2] Stefan Brecht, Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, Vol. 1 (London: Methuen, 1988), 86-87.

[3] Brecht, Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, Vol. 1, 85.

[4] Richard Walsh, Radical Theatre in the Sixties and Seventies (Keele, UK: British Association for American Studies, 1993).

[5] Brecht, Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, Vol. 1, 159-61.

[6] Robert Craig Hamilton, “The Bread and Puppet Theatre of Peter Schumann: History and Analysis” (Dissertation, Indiana University, 1978), 33.

[7] Jim Henson to Ingram Merrill Foundation, November 12, 1965, enclosed in a letter from Jim Henson to Peter Schumann, November 11, 1965 folder 13, box 1, Bread and Puppet Theater Collection, University of Vermont Libraries Special Collections (hereafter" BPT Collection").

[8] Hamilton, “The Bread and Puppet Theatre of Peter Schumann,” 36-39.

[9] James Martin Harding and Cindy Rosenthal, eds. Restaging the Sixties: Radical Theaters and Their Legacies (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007), 354. Elka Schumann’s centrality to the work of Bread and Puppet has been underappreciated in the literature and restoring her contributions to the record is part of my ongoing research and writing.

[10] Brecht, Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, Vol. 1, 478.

[11] Dedication page for Fire, with explanation and New York Times articles, folder 15, box 1, BPT Collection.

[12] Quoted in Brecht, Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, Vol. 1, footnote 3, 647.

[13] Quoted in id., 661.

[14] Brown, et al., “With the Bread & Puppet Theatre,” 70.

[15] Id., 67.

[16] Helen Brown, Jane Seitz, Peter Schumann, Kelly Morris, and Richard Schechner, “With the Bread & Puppet Theatre: An Interview with Peter Schumann,” TDR 12, no. 2 (January 1, 1968), 64.

[17] Brecht, Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, Vol. 2, 485; Deb Ellis, Six Vermont Artists, DVD (Montpelier, Vermont: Vermont Arts Council, 2009).

[18] Jim Henson to Ingram Merrill Foundation, November 12, 1965, folder 13, box 1, BPT Collection.

[19] See letters in folder 48, box 1, BPT Collection.

[20] Esther Gollobin to Peter Schumann, March 26, 1967, folder 16, box 1, BPT Collection.

[21] Silvia D. Spitta, "Revisiting the Sixties and Refusing Trash: Preamble to and Interview with Peter Schumann of Bread and Puppet Theater," boundary 2 36:1 (Spring 2009)," 121.

[22] Spitta, "Revisiting the Sixties and Refusing Trash," 119.

[23] Quoted in Brecht, Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, Vol. 1, 691-693.

[24] Jeff Farber and Grace Paley, Brother Bread, Sister Puppet, DVD (New York: The Cinema Guild, Inc., 2007).

[25] Bread and Puppet Theater Homepage, accessed April 2, 2012, http://breadandpuppet.org.