“A Series of Blunders and Broken Promises”: IS 201 as a Turning Point

By Michael R. Glass

Editors' Note: This is part of a roundtable series,“New Histories of Education in New York City.” For an introduction and overview, click here.

In our first post, Michael R. Glass details the “twelve years of conflicts that preceded the opening of IS 201.” Desegregation, Glass demonstrates, was not about “wanting to sit next to white folks,” but a strategy deployed in service to a “broad, transformative vision of educational equity.” Community control was a strategy, too, developed in response to bureaucratic intransigence and massive popular resistance on the part of white, middle-class communities. Across these twelve years, parent activists sought both community empowerment and an equitable distribution of municipal resources, struggles that continue in our own time.

Teachers stood in front of empty classrooms. The hallways, the cafeteria, the gymnasium -- all were eerily silent. When Intermediate School 201 first opened its doors fifty years ago, none of its five hundred students reported to the gleaming new building. Instead, it sat vacant for ten long days as an intense standoff ensued between parent-activists and school officials.

The school’s opening was supposed to be celebratory. After all, the Board of Education had unveiled IS 201 as a showcase school. Perched atop fourteen-foot concrete stilts on the corner of Madison Avenue and 127th Street in East Harlem, it towered over the neighborhood like a lighthouse. It cost five million dollars to build. It was the first fully-air-conditioned school in the city. And with extensive offerings in art, music, and foreign languages, its curriculum would be state of the art.

It was also supposed to be integrated.

Back in 1958, when the city announced plans for a new junior high, community leaders were cautiously optimistic: a new school was sorely needed to relieve overcrowding, yet if placed in the heart of Harlem, it would further entrench segregation. Officials maintained that the site, a stone’s throw from the Triborough Bridge, would promote integration by drawing students from adjacent white neighborhoods in the Bronx and Queens. As the school was being built, the surrounding areas were showered with ten thousand pamphlets extolling the school’s virtues and inviting parents to enroll their children.

Not a single white family signed up. In early 1966, the Board revealed the “integration” that would prevail at the school: a student body 50 percent African American and 50 percent Puerto Rican. Community leaders were incensed. Throughout the bitter controversy that accompanied the school’s opening in September 1966, a handwritten sign hung out front of the building. It read, “Harlem Has Been Betrayed.”[1]

IS 201 today. None of the classrooms have windows, and the few hallway windows are covered in metal cages. Architects designed the building to be soundproof and lightproof in order to block out the “delinquent” influences of the surrounding neighborhood and “heighten the students’ concentration.”

In meetings with school officials, activists drew a line in the sand. “Either they bring white children in to integrate IS 201 or let the community run the school,” declared the president of Harlem’s Parent Teacher Association alliance.[2] Such community control would entail the right to hire and dismiss teachers; to establish curriculum standards; and to direct the allocation of funds. It was a radical new idea.

What could account for this stunning turn of events? Local media outlets had readymade explanations. The editors of the New York Times, for instance, lamented that Harlem activists had been overtaken by “misguided ideologues of Black Nationalism less interested in improved education than in a general challenge of all institutions.”[3] Most historians have followed suit, depicting IS 201 as a Rubicon with school integration on one side, and a new era of community control on the other. It is here, we are told, that integration “failed” and, in its ashes, Black Power arose.[4]

But these accounts erase the twelve years of conflicts that preceded the opening of IS 201. More than anything else, activists’ shifting strategies grew out of a decade of accumulated experiences. Time and again, the Board’s halting attempts at school integration, though often taken in the name educational equality, tended to reinforce and deepen racial inequality. These experiences taught harsh lessons about which students city authorities valued most. Rather than a sharp departure, therefore, IS 201 must be seen as part and parcel of a long struggle for quality, integrated education in New York City’s segregated schools—a struggle that began long before 1966, and a struggle that, in many ways, continues today.

Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, whose famed “doll tests” figured prominently in the 1954 Brown decision, was an early critic of school segregation in New York City.

School segregation had been at the top of the city’s agenda ever since Dr. Kenneth B. Clark delivered a series of scathing speeches in early 1954. Clark publicly denounced the conditions in the city’s predominantly black schools: overcrowded classrooms, crumbling buildings, a preponderance of inexperienced or unlicensed teachers, and a watered-down curriculum. Under such conditions, Clark alleged, “These children not only feel inferior, but are inferior.” Clark was no ordinary critic—he had been a star witness in the Brown v. Board of Education cases recently argued before the Supreme Court.[5]

The speeches sent shockwaves through the city. Most New Yorkers believed segregation was something that existed in the Jim Crow South, not their own backyards. Schools Superintendent William Jansen immediately went on the offensive. He told reporters that Clark’s charges had “no basis in fact.” “We did not provide Harlem with segregation,” Jansen maintained. “We have natural segregation here—it’s accidental.”[6]

Yet as pressure from civil rights organizations mounted, school officials soon shifted the city’s position. In December 1954, seven months after the Supreme Court declared separate educational facilities “inherently unequal,” the Board announced a new goal—to integrate the city’s schools “as quickly as practicable.”[7] In addition, they announced the formation of a Commission on Integration (COI), tasked with studying the issue and recommending steps to promote integration. In late 1956, the COI announced its preliminary proposals. The most controversial included making racial integration the “cardinal principle” in drawing school zoning lines and transferring experienced teachers to the most underserved schools. In short order, a flood of more than 2,000 protest letters poured into City Hall. The complaints came mainly from white parents, who claimed the zoning proposals infringed on their right to a neighborhood school; and from representatives of teachers’ unions, who warned that any “forced transfers” would destroy morale, leading to a mass exodus of teachers from the city system.[8]

Mae Mallory with her daughter, Patricia, in 1957

Given the heated disagreements, the Board held a series of public hearings to allow comments on the proposals. Late in the evening at a packed-house hearing in January 1957, Mae Mallory, a thirty-year-old African American woman, rose to speak on behalf of an elementary school in Harlem. “We feel that if the Board of Education approves and implements these two reports…[it] will correct some of the injustice done to our children,” she declared. “Our children want to learn and they certainly have the ability to learn. What they need is the opportunity.” The crowd cheered as Mallory returned to her seat.[9]

Though the Board eventually endorsed the reports, hardly anything changed. Frustrated by the prevarications, Mallory and a group of parents formed the Parents’ Committee for Better Education (PCBE), a grassroots organization that advocated for better educational facilities in Harlem, as well as integrated schools citywide. Its membership quickly grew to over 400 parents.

The overriding concern for PCBE members was to gain access to educational resources—such as modern facilities, rigorous academic programs, and experienced teachers—that were disproportionately concentrated in predominantly white schools.[10]Accordingly, they saw integration as a useful means for achieving educational equity, not an end in itself. As Mallory later recounted, it had “nothing to do with wanting to sit next to white folks.”[11] Yet after a year of letters, petitions, marches, and meetings with the city officials bore few tangible improvements, Mallory and eight other parents turned to direct action. When schools opened in September 1958, the nine parents kept their children home, demanding they be transferred to schools with “higher standards.” As the group’s spokeswoman explained, “If that’s the only school for [my son] to attend, he will not go to school. I’d rather go to jail than have my child further abused intellectually.”[12] Their boycott lasted 156 days. Five months and several court appearances later, city officials acceded to their demands, allowing the students to switch to a school with an innovative new curriculum. While undoubtedly a victory, the Harlem Nine boycott set no precedent; others in a similar situation were left to fend for themselves.[13]

Color lines similarly hemmed in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where predominantly black and Puerto Rican elementary schools were so overcrowded that classes ran on two shifts—one from 8:30 to 12:30, the other from 11:30 to 3:30—due to a lack of space. Meanwhile, classrooms sat half-empty in Glendale and Ridgewood, neighboring all-white sections of Queens. After an outcry from the local NAACP branch, the Board announced it would allow 400 third, fourth, and fifth graders to transfer from Bedford-Stuyvesant to Glendale-Ridgewood in the fall of 1959. In the hopes of mitigating white resistance, officials repeatedly said the transfers were intended merely to relieve congestion, not promote integration.[14] This, however, was a false dichotomy: quite clearly, Bed-Stuy schools were overcrowded because they were segregated.

Notwithstanding the careful language, many Glendale-Ridgewood residents spent the summer mobilizing against the one-way transfers. On the first day of school in September 1959, close to half the students in the five receiving schools were kept home in protest. Undeterred, six busloads of kids, all between nine and eleven years old, braved the ten-minute ride from Bed-Stuy to their new schools. Upon arriving, they clung to one another as they shuffled through a gauntlet of picketers, police officers, and newsmen. At one school, vandals had scrawled “Blacks Go Home” on the exterior of the building. At another, there was a brief bomb scare. Despite the remarkable courage displayed by the young children, media accounts obsessed over the causes of the “white boycott,” implicitly portraying the transfers as a burden chiefly borne by Glendale-Ridgewood residents. It was as if the transferred students were invisible.[15]

The following year, the city embarked on a new policy of “Open Enrollment,” whereby any pupil in a school with more than 85 percent black or Puerto Rican students could transfer to schools with excess capacity. The Board said the new voluntary integration program would “provide the best possible opportunities for children attending schools in segregated areas.” However, the program’s administration belied the lofty rhetoric. Indeed, the stipulations proved onerous: the application window was a mere fifteen days; many principals reportedly discouraged pupils from applying; and parents were responsible for all transportation costs. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the response rate was low. Of the 20,000 children eligible in September 1960, only 681 returned the application.[16] Still, plenty of families put themselves on the front lines of the integration battle. “I knew my children were not receiving the best education,” related one mother from Bed-Stuy, “but I did not know how much they were being cheated…until I took advantage of Open Enrollment.”[17]

A group of Glendale-Ridgewood parents protest in front of City Hall in June 1959

While many parents shuttled their children across the city to better-resourced schools, the limits of Open Enrollment bred frustration. Under the voluntary plan, black and Puerto Rican families shouldered all the burdens: they rode the buses; they left the comforts of their home neighborhoods; and they were the ones stigmatized in unfamiliar settings. During the early 1960s, grassroots activists began calling for a citywide integration program with two-way transfers and a firm timetable for implementation. City leaders, for their part, scoffed at the idea: “This is a Board of Education, not a Board of Integration or Transportation,” fumed the president of the Board.[18] After negotiations stalled, civil rights leaders shifted their plans for a citywide boycott into high gear.

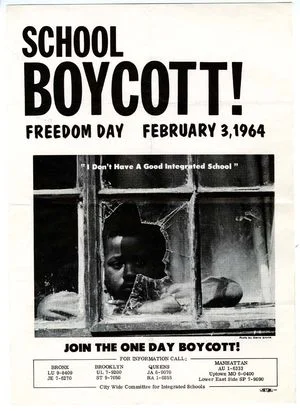

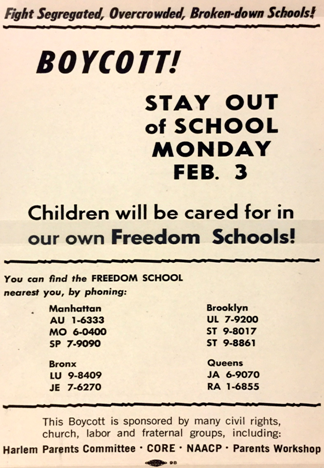

On February 3, 1964, over 460,000 students boycotted school, making it the largest civil rights demonstration in United States history. A massive show of solidarity among blacks, Puerto Ricans, and white liberals, it marked the peak of the school integration movement. Pickets marched in front of 300 schools. Over 3,500 demonstrators chanted “Jim Crow Must Go” in front of Board headquarters. And boycotting students attended “Freedom Schools” in churches and community centers, where they discussed black and Puerto Rican history.[19] As the ten-year movement makes clear, activists never saw integration, quality education, and community empowerment as mutually exclusive; rather, all were entwined in a broad, transformative vision of educational equity.

On the heels of the citywide boycott, the Board announced twenty sets of elementary school pairings for the fall of 1964 (that is, all pupils from both schools would attend one school for the first three grades, and the other for the last three). By focusing on fringe areas where predominantly black and Puerto Rican schools bordered predominantly white schools, the plan relied on geographic proximity to promote integration. Although the proposal met the integrationists’ demand for two-way transfers, it also, in effect, excluded Harlem and Bed-Stuy altogether by requiring the paired schools to be no more than one and a half miles apart.[20]

Despite its limited nature, the plan met fierce resistance. A group of white parents formed Parents and Taxpayers (PAT), a citywide umbrella organization focused on opposing the pairings. “Those programs…would be an abdication of all our rights,” asserted Rosemary Gunning, executive secretary of PAT. “We’re not going to have totalitarian decrees forced down our throats.”[21] And, by mimicking the tactics of civil rights protestors, they made themselves heard. On a snowy morning in March 1964, over 15,000 PAT members trudged over the Brooklyn Bridge to City Hall, where they held a massive rally against school integration.[22] A New York Times poll taken after the PAT demonstration revealed that 80 percent of white New Yorkers opposed the pairings.[23] Facing such hostility, the Board reduced the number of paired schools from twenty to four. Thus, in a city with over one million public school students, the pairing plan had been whittled down to the point where it ultimately involved only 2,000 students.

But PAT kept up the fight, claiming the pairings were a precursor to citywide integration. When schools opened in September 1964, PAT orchestrated a two-day citywide boycott. On the opening day, over 275,000 students stayed home in protest; on the second day, over 233,000 did. Hardest hit were the eight paired schools: three schools in Brooklyn, and one in Queens, reported less than 10 percent attendance.[24]

Of course, plenty of students did show up to the paired schools: they boarded buses, crossed invisible neighborhood boundaries, and presented themselves at their new schools—only to be greeted by irate crowds and mostly-empty classrooms.

This was the backdrop against which the IS 201 controversy erupted in the summer of 1966. Faced with a shifting political landscape, a group of seasoned activists in Harlem drew their own conclusions. In a letter to city officials, the IS 201 parents’ committee said the fiasco was but the latest in “a series of blunders and broken promises on the part of the Board of Education.” They continued, “If 201 [is] destined to be another segregated, ghetto school, then the community must have the power to prevent a repetition of educational failure that [is] occurring in all the other segregated schools.”[25] As evidenced by these statements, the emergent call for community control grew organically out of previous struggles. Neither an ending nor a beginning, IS 201 was a turning point in a historic—and still ongoing—search for educational justice in an unequal society.

Much has changed over the past half-century. New issues headline contemporary education debates, including: charter schools, standardized testing, teacher evaluations, and gentrification. Today New York City schools are far more diverse, serving students from literally all over the world. But New York City, like the rest of American society, remains starkly segregated by both race and class. On this fiftieth anniversary, it is worth reflecting on the basic questions raised at IS 201: Who does a public school belong to? What is the relationship between education and democracy? Between opportunities and outcomes? Finally, with the benefit of hindsight, we must ask yet again: Can segregated schools ever truly be equal?

Michael Glass is a doctoral candidate at Princeton University.

[1] “Integration: The Sorry Struggle of I.S. 201,” TIME Magazine, September 30, 1966.

[2] “Board Sets Talks in School Dispute,” New York Times, September 11, 1966.

[3] “Classes at I.S. 201,” editorial, New York Times, September 23, 1966.

[4] For example, see Diane Ravitch, The Great School Wars: A History of the New York City Public Schools (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974); Clarence Taylor, Knocking at Our Own Door: Milton A. Galamison and the Struggle to Integrate New York City Schools (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2001); Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); Daniel H. Perlstein, Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004).

[5] “Citizens Should Demand Study of School System,” New York Amsterdam News, Feb. 27, 1954; Kenneth B. Clark, “Segregated Schools in New York City,” (speech at “Children Apart,” New York City, New York, April 24, 1954), 7-15, Series 472, Box 1, Folder 2A, Board of Education Records (hereafter BOE), New York City Municipal Archives (hereafter NYCMA); “Harlem Students Learn Inferiority,” New York Amsterdam News, May 1, 1954.

[6] “P.S. Super OK’s N.Y. Segregation,” New York Amsterdam News, June 5, 1954.

[7] “Preliminary Statement of Board of Education Resolution for Action,” Dec. 23 1954, 1-4, Series 472, Box 1, Folder 2D, BOE, NYCMA.

[8] “Jansen Will Face Critics in Queens,” New York Times, March 23, 1957. For some of the letters, see Commission on Integration records, Series 261, Box 1, Folder 10, BOE, NYCMA.

[9] Testimony by Mae Mallory (Speaker #38), representing the P.T.A. of P.S. 10, Board of Education Public Hearing, Jan. 17, 1957, Series 261, Box 2, Folder 13-14, BOE, NYCMA; “Teacher Groups Oppose Integrating NY Schools,” New York Amsterdam News, Feb. 2, 1957.

[10] On the dialectic between racial integration and community empowerment, see Russell Rickford, “Integration, Black Nationalism, and Radical Democratic Transformation in African American Philosophies of Education, 1965-74,” in The New Black History: Revisiting the Second Reconstruction, eds. Manning Marable and Elizabeth Kai Hinton (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 287-317.

[11] Mae Mallory, interview by Malaika Lumumba, 1970, 15, Ralph Bunche Oral History Collection, Moorland-Spingard Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C.

[12] “Negroes Boycott 4 Schools Here,” New York Herald Tribune, Sep. 9, 1958.

[13] For more on the Harlem Nine boycott, see Adina Back, “Exposing the ‘Whole Segregation Myth’: The Harlem Nine and New York City’s School Desegregation Battle,” in Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940 – 1980, eds. Jeanne Theoharris and Komozi Woodard, 65-91.

[14] City Commission on Human Rights of New York City, A Tale of Two Boroughs: A School Integration Success Story, Sept. 1961, 4.

[15] “971 Whites Boycott 5 Schools in Queens,” New York Herald Tribune, Sept. 15, 1959; “Whites in Queens Keep Pupils Home in Transfer Fight,” New York Times, Sept. 15, 1959.

[16] “Parents of 329 Children Ask Shift to White Schools,” New York Herald Tribune, September 16, 1960; “More Parents Balk at Pupil Transfers,” New York Herald Tribune, October 13, 1960; Ravitch, The Great School Wars, 262; Rogers, 110 Livingston Street, 17, 30-32.

[17] Rosalie Mosely quoted in Parents Workshop for Equality in New York City Schools, newsletter, June 1963, in Annie Stein Papers, Box 20, Folder 6, Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

[18] “Battle Over School Integration,” editorial, New York Times, December 27, 1963.

[19] “Boycott Cripples City Schools; Absences 360,000 Above Normal; Negroes and Puerto Ricans Unite,” New York Times, Feb. 4, 1964; “Freedom School Staffs Varied But Classes Followed Pattern,” New York Times, Feb. 4, 1964.

[20] “School Board Outlines a 3-Year Plan For Racial Balance and Full Sessions,” New York Times, Jan. 30, 1964.

[21] “New York City Is Still Seeking Integration Solution,” The Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution, Aug. 30, 1964. “Integration Furor: White Parents in New York Protest Plan to ‘Pair’ Schools,” Wall Street Journal, April 23, 1964.

[22] “More Than 10,000 March in Protest of School Pairing,” New York Times, March 13, 1964.

[23] “Poll Shows Whites in City Resent Civil Rights Drive.” New York Times, Sept. 21, 1964.

[24] “275,638 Stay Home in Integration Boycott; Total 175,000 Over Normal,” New York Times, Sept. 15, 1964; “School Boycott Eases on 2D Day; Gross Stays Firm,” New York Times, Sept. 16, 1964.

[25] Negotiating Committee for I.S. 201, “Proposal for Educational Excellence for I.S. 201 and its Feeder Schools,” 1; “Sequence of Events Surrounding Community Involvement with Public School 201,” 4, both in Folder: “School Discrimination, Harlem, New York, 1966,” Congress of Racial Equality Papers, Part 2: Scholarship, Educational and Defense Fund for Racial Equality, 1960-1976, Series C: Legal Department Files, accessed via ProQuest History Vault.

For more on school segregation in New York City, see:

Jelani Cobb, “Class Notes: What’s Really at Stake When a School Closes?,” The New Yorker, August 31, 2015.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Choosing a School for My Daughter in a Segregated City,” New York Times Magazine, June 9, 2016.

“Demand for School Integration Leads to a Massive Boycott—in New York City,” WNYC, February 3, 2016.